Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups / Arts, Culture, Sports

IATMUL PEOPLE

The Iatmul (pronounced YAHT-mool, also spelled Yatmul) inhabit about two dozen autonomous villages along the Middle Sepik River in East Sepik Province. The Iatmul are best known for their art, men’s houses, elaborate totemic systems, and male initiation ceremonies, as well as for the naven ritual, first studied by anthropologist Gregory Bateson in the 1920s and 1930s. Today, they are also known to tourists and scholars alike through the 1988 documentary Cannibal Tours. [Source: Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

According to the Joshua Project, the Iatmul population in the 2020s was about 16,000, up from roughly 10,000 in the 1990s and 12,000 in the 2000s. They identify with three territorial subgroups: Eastern (Woliagui) Central (Palimbei) and Western (Nyaura) Iatmul territory stretches roughly 230 kilometers (140 miles) upstream from the river’s mouth and extends another 170 kilometers inland. The Middle Sepik region is dominated by the vast, meandering river, which floods seasonally, transforming the valley into a vast lake. Floating grass islands — sometimes carrying trees and birds — drift with the current as floodwaters reshape the landscape each year. Life for the Iatmul alternates between two main seasons, wet and dry, each lasting about five months, separated by brief transitional periods.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEPIK RIVER GROUPS: WHERE THEY LIVE, ART, SPIRIT HOUSES, CROCODILES ioa. factsanddetails.com

KWOMA (A SEPIK RIVER TRIBE): HISTORY, LIFE, ART ioa. factsanddetails.com

EAST (LOWER) SEPIK PEOPLE — BOIKEN, MURIK, SAWIYANO — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE LOWER (EAST) SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ABELAM AND ARAPESH OF THE SEPIK RIVER: LIVES, HISTORY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE: MASKS, FIGURES AND SHELL RINGS ioa. factsanddetails.com

BIWAT (MUNDUGUMOR): LIFE, RELIGION, FAMILY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

IATMUL PEOPLE OF THE SEPIK RIVER: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa. factsanddetails.com

WEST SEPIK HIGHLANDS PEOPLE — WAPI, TELEFOL, MIAN, GNAU, BIMIN — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

Iatmul Art

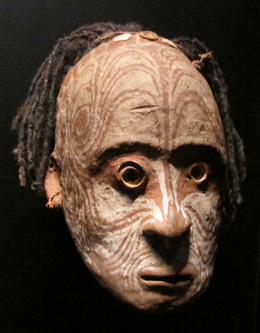

The art of the Iatmul people is the most well-represented of all the indigenous peoples of Papua New Guinea. However, few people have much knowledge of or understanding about the complex culture that produced such appealing sculptures, carvings, and masks. Almost all art objects were used in ritual contexts and only through such use did they receive meaning. Also famous are the skulls overmodeled with clay and then painted. Apart from such preservable artifacts, Iatmul art consists of ephemeral art, such as body painting and decorations made of leaves, flowers, and feathers. [Source: Wikipedia, Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Iatmul art is well known for its superb carvings, which were usually painted in a curvilinear style. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The latmul people are among the most prolific and accomplished of the region 's wood-carvers. As in other Sepik cultures the primary focus of artistic expression among the latmul is the men's ceremonial houses. Most Iatmul villages specialize in the production of different kinds of goods that are used for trading. Aibom is well known for pottery, which traditionally was traded for sago throughout the Iatmul area; today it is sold for money as well. Chambri, a non-latmul border village to the south, specializes in firmly plaited mosquito bags manufactured by women. In all Sepik villages, where mosquitoes and malaria are endemic, these bags are used by entire families sleeping in them communally. Tambunum is renowned for its plaited bags, also produced by women, with various Colored patterns.

Iatmul carvings are among the most artistic in New Guinea. Men began producing them in large quantities when they found early travelers and art dealers interested in them. Anthropologists argue that Iatmul attained superiority and control over their neighbors by being a "cultural factory," producing sacred artifacts, spells, and knowledge and then exporting them. However, no reliable information confirming this can be found, except for an exchange of ritual items that must have taken place in both directions as indicated by Abelam paintings collected by early German explorers in Iatmul villages. As far as can be determined, irregular trading expeditions took place up southern tributaries and vice versa, with paint, edible earth, and bark used for medicinal purposes imported from these areas. Shell rings, turtleshell ornaments, and other valuables arrived in the Middle Sepik through the Abelam and Sawos regions and also from the upper regions of the Sepik River. Stone blades as well as pearlshells came from the highlands to the south. *\

Iatmul Ceremonial Houses

The men’s house (tambaran or haus tambaran) embodies Iatmul spirituality and social order. In the past, the house posts were beautifully carved to depict parts of clan mythology. These carvings constituted the foundation of not only the house, but also the entire society. The building on the rectangular dance ground represented the first grass island that floated down the Sepik River, as described in a creation myth. At the same time, it represented the first crocodile: the primeval ancestor who emerged from the depths of the flood. [Source: Wikipedia, Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Today, the ground level of the men's house is used by initiated men in everyday life. It contains slit gongs, fireplaces, sitting platforms, and ritual objects of minor importance. The upper floor is mainly used for rituals and is where the long flutes and other sacred paraphernalia are kept. Iatmul culture is rich in myths that explain how everything came into being.

A 1973 photograph shows an latmul men's ceremonial house in the village of Korogo in the Middle Sepik Region of Papua New Guinea. The house itself is conceived as the body of a primordial woman, whose face appears as the large gable mask that adorns the facade. A mai mask performance is underway in the foreground. A 1955 photograph shows the interior of an latmul house in Aibom village. Many of the family's possessions are stored in string bags hung from two large suspension hooks, which are carved in the form of ancestor figures. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Iatmul Masks

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The mai masks of the latmul people are among the best known of all New Guinea art forms. The form and ornamentation of mai masks vary considerably across the latmul region, but all exhibit the same oblong face and greatly elongated nose that extends into a mo/at-an archlike form that joins the nose to the chin or, in some examples, extends below it. With its deep-set eyes, prominent brow ridges, and extremely narrow, strongly convex face, the present mask is typical of the Nyaula (Western) latmul. Worn by young men and boys, mai masks are not placed di redly on the face but attached to large conical basketry costumes (mai /age), which are worn over the head and upper body of the dancer. Covered with brightly colored leaves, flowers, and feathers, the costumes are fringed with grass skirts that extend to the wearer's knees. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

One mai mask in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made by the Nyaula (Western) latmul people in middle Sepik region in the late 19th-early 20th century. Made of wood, paint, and fish vertebrae, it is 28 inches (71.1 centimeters) tall. Although the mai dancers make use of the men's house during the performance, mai masks, unlike most other types, are not stored there. Instead, each pair or group of mai are the property of a particular clan and are kept in the dwelling of the clan elder when not in use.

In addition to the masks and bamboo tubes, the term mai is used to refer to the small snail shells that are inlaid into a hardened claylike substance that is typically applied to the edges of the masks. Some authors state that the masks take their name from these shells. Masks existing today were likely once adorned in this fashion, with the clay and shells now lost.

An Initiation Mask at the Metropolitan Museum of Art made by an Iatmul artist in the early to mid-20th century is fashioned from fiber, cassowary feathers and paint. Produced in Kapriman village on the Korewori or Blackwater River in the Middle Sepik, region, it is 39.5 inches high, with a width of 16.5 inches (100.3 × 41.9 centimeters).

Iatmul Mai Mask Performance

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Within the capacious costume the dancer carries a bamboo tube, also called a mai, through which he sings in falsetto, the tube both amplifying and transforming the tone of ris voice. Mai masks are carved and danced in pairs that represent supernatural siblings, either an older and younger brother or an older and younger sister: The masks are often performed in groups of four, with the two brothers and the two sisters dancing together. The identity and, at times, the decoration of the masks embody the dualism central to much of latmul cosmology, which divides many phenomena into pairs of opposites (male/female, older/ younger, day/night) that together constitute the larger whole. According to oral tradition, the mai masks and bamboo tubes did not originate among the latmul but came from the mountains to the north (inhabited by the Abelam and Boiken peoples today) and were obtained from supernatural beings captured by the latmul. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The men of Kararau village gave the following account: [W]hen the earth had just been created and was slowly hardening, there were many men and many women. At that time we did not yet possess the bamboo tubes we call mai.... Two people [supernatural beings] lived near a mountain that lies north of our region. Their voices sounded through short bamboo tubes. We heard it; all our ancestors heard it and wanted to know where the voices were coming from. They found [the beings] and saw the two of them.

[The latmul assembled warriors and captured the two beings].... They took them back home.... The two [beings] said "It 's all right, you can let go of us, then we 'll perform our [ceremonial dance] for you."... So the men let go of them. The two performed the [mai mask performance] and everyone watched.... All of us men took over the [ceremonial dance] of the two mai. Then the two returned. Today we still do it as the two did it then. The two brothers had two sisters. Now we do [the performance] the way the four of them did it then.

Mai mask performances are lavishly staged affairs and begin with the erection of a fence around part of the village dancing ground, creating a compound in which the dancers ready themselves. Inside the compound, the men construct a large, raised platform with a backdrop representing the mountains from which the masks originated; from the platform a broad ramp (weinbangge) extends over the wall to the ground outside.

The men then light smoldering fires whose smoke is said to represent the burning of the grasslands that lie between the latmul and the mountains. As the smoke clears, the brilliantly costumed mai maskers burst onto the platform from behind the backdrop and stride boldly down the ramp. On reaching the ground, the dancers, their voices emanating from the bamboo tubes beneath the costumes, are met by the women of the village, who dance toward the figures and accompany them to the dancing ground. At the climax of the performance the dancing mai encounter the baomi, a large peeled log with vines attached to the ends, which allow it to be lifted off the ground. As two of the masked figures lift the baomi, another jumps over it, briefly drums on the suspended trunk, and sounds a short flute from beneath his costume. The mai then continue to dance, periodically withdrawing into and emerging from the men's ceremonial house, into which they retire at the end of the performance.

Performed by young initiated men and boys, the mai dance forms the junior counterpart to the sacred slit-gong ceremony of the male elders. Like the sacred slit gongs, mai are ultimately manifestations of the powerful supernatural beings known as waken. However, many aspects of the nature and significance of the masks and the activities during the performance remain veiled in secrecy.'" A 1979 photograph shows a mai mask performance in the latmul village of Kararau. The photo captures the climax of the dance, in which the central masked figure jumps over the baomi (a barkless log), which is raised off the ground by two other mai dancers.

Iatmul Debating Stool (Kawa rigit)

Eric Kjellgren wrote: In the central and most sacred area of latmul men's ceremonial houses stood the kawa rigit, or debating stool, which was and, in some villages, remains the focal point of male religious and political life. Although the lower portion of these works is carved in the form of the low stools used by the latmul, kawa rigit are sacred objects and are never used as seats; they serve instead as rhetorical aids during debates. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

In each village all significant matters must be debated in the presence of its most prominent ancestor, whose image forms the back of the stool. Most debates center on esoteric religious matters, primarily concerning the rightful ownership of the supernaturally powerful names of ancestors, spirits, totemic animals, or sacred objects.

The name kawa rigit means, literally, "the seat of leaves"-a reference to the manner in which the stools are used during the debates. As each speaker rises in turn, he takes up several bundles of leaves, which lie on the seat of the stool, and strikes the seat with them. As he progresses with his argument, he emphasizes each of his main points by placing a leaf or bundle of leaves on the seat to summon the spirit to witness each point, until all the leaves have been put down. He then gathers the bun dies up again, strikes the seat, and repeats the process as necessary until the completion of his speech, which he ends by striking a final blow to the seat and placing the leaves on the seat, to be taken up by the following speaker.

A boisterous process, combining religious erudition with aggression, humor, and outright mockery of the opposition, latmul debates, although they usually end peaceably, at times erupt into violence. The anthropologist Gregory Bateson, who witnessed a number of debates in 1929 and 1930, described how the two sides might come to blows: As the debate proceeds, both sides become more excited and some of the men leap to their feet, dancing with their spears in their hands and threatening an immediate resort to violence; but after a while they subside and the debate goes on.

This dancing may occur three or four times in a single debate without any actual brawling, and then suddenly some exasperated speaker will go to the "root" of the matter and declaim some esoteric secret about the totemic ancestors of the other side, miming one of their cherished myths in a contemptuous dance. Before his pantomime has finished a brawl will have started which may lead to serious injuries and be followed by a long feud of killings by [malevolent magic]. The ancestor depicted on the kawa rigit is not only a witness to debates; the ancestral spirit is also consulted prior to the initiation of young boys and, formerly, in planning head-hunting raids on enemy villages. The imagery of the kawa rigit combines two basic forms: the low, round stool, whose seat and short, bent legs are visible here, and the upright back, formed by the figure or head of the ancestor-an image that embodies both the most important ancestor of the village and the leading ancestor of the clan on whose lands the men's house stands.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art contains a kawa rigit (debating stool) made by the Iatmul people in the middle Sepik region in the 19th century. Made of wood, paint and shell, it is 33 feet (10 meters) tall. In this work the ancestor is shown as a muscular standing male figure adorned in the manner of an latmul man. His face is decorated with curvilinear designs similar to those painted on the human face on ceremonial occasions, while his shoulders bear incised designs representing the serification marks made on the bodies of men during initiation. A 1930 photograph shows an latmul man of Malingai village posing next to the debating stool at the center of a men's ceremonial house. He holds bundles of leaves, which are placed upon the stool or used to strike the seat to emphasize important points during debates.

Ceremonial Lime Containers (Bandi Na Iavo)

Eric Kjellgren wrote: As in many Western Pacific cultures, the peoples of the middle Sepik River use betel nut. Betel nut is the fruit of the areca palm, which, when chewed together with lime made from burnt coral or shell and the leaf of a particular vine, produces a mild stimulant effect. Among the Iatmul and neighboring groups, equipment for betelnut chewing has become especially elaborate, and both the containers (iavo) used to store the powdered lime and the spatulas (tap) used to scoop it from the containers serve symbolic and religious as well as practical functions. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

During male initiation rites, ceremonial lime containers (bandi na iavo) made from bamboo, were presented to the newly initiated boys by their maternal uncles. When making their first public appearance following the rites, the initiates proudly displayed the containers, together with other ornaments and accessories, as marks of their newly achieved status.

The top of the bandi na iavo had only a small hole to allow for the insertion of the lime spatula, but the lower portion was frequently adorned with elaborate decorative wood carvings depicting totemic animals and other supernatural beings. Some of these ornate lime containers were produced by the Chambri people and, to a lesser extent, by the latmul artists of Aibom village, both of whom specialized in the production of these objects, which they traded to surrounding communities.

Lime spatulas (tap) were regarded as symbols of male pride and aggression. They were often greatly elongated, with the upper portion intricately carved. In the past the tap of prominent warriors were embellished with long tassels, each of which symbolized an enemy slain in battle. The lower ends of latmul lime sticks were carved with a series of serrated ridges, which allowed the spatula and container to be used as a noisemaker, to emphasize the emotional state of the owner. As a signal of their confidence or displeasure, latmul men rapidly thrust the lime stick in and out of the mouth of the container, so that the raised ridges rubbed against the edge of the hole, producing a harsh, grating noise. This use of spatulas and lime containers as noisemakers was considered such a quintessentially male activity that it formed a central feature of portions of the great ceremonial cycle known as naven, in which the customary gender roles were reversed. Here the women took up the clothing, ornaments, and accessories of men, strutting about and grating their lime sticks within the containers, taking so much pleasure in irreverently and humorously imitating the personalities and actions of men that they sometimes wore out the lime sticks with their efforts, as the anthropologist Gregory Bateson described: In [male costume) the women were ver proud of themselves.

They walked about flaunting their feathers and grating their lime sticks in the boxes [lime containers], producing the loud sound, which men use to express anger, pride and assertiveness. Indeed so great was their pleasure in this particular detail of male behavior that the husband of one of them complained sorrowful! that his wife had worn away all the serrations on his lime stick so that it would no longer make a sound. Today this older form of lime container has mostly been replaced by boxes made from metal or plastic. However, bamboo and gourd lime containers continue to be produced and used in ceremonial contexts.

One Ceremonial Lime Container (Bandi Na Iavo) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made by the Chambri or Iatmul people in the middle Sepik region in the late 19th-early 20th century. Made of wood, bamboo, fiber and paint, it is 22.4 inches (56.5 centimeters) tall. Another from the same time and place by the latmul people is made of wood and paint and is 29 inches (75.9 centimeters) tall. A 1930 photograph shows an latmul man of Mindimbit village in full dress regalia, carrying an elaborate lime container equipped with an elongated lime stick adorned with a series of tassels, each of which represents an enemy slain in battle.

Iatmul Ceremonial Fence Elements

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Although few examples survive today, in former times each latmul village typically had at least one set of three men's ceremonial houses standing in an extensive dancing ground. At either end of each ceremonial house the latmul constructed a small raised earthen mound (wok), which they planted with totemic trees, bushes, and other plants. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

During some rituals the ceremonial house was likened to a canoe floating on the river and was "moored" by tying it with a rope to a palm tree growing in the wak. In the past, after a successful head-hunting raid, the bodies of slain enemies were laid upon the wok among the sacred plants. In some cases the mound was enclosed by a wood fence, whose components included postlike wood images with large, brightly painted heads or busts portraying ancestral spirits.

A Ceremonial Fence Element in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made in Kararau village in the middle Sepik region by the Iatmul people. Dated to the late 19th-early 20th century, it is made of wood, paint and shell and is 60.5 inches high, with a width of 11.5 and a depth of 5.37 inches (153.7 × 29.2 × 13.7 centimeters). The ancestor in this work is wearing elements of ceremonial finery. The geometric patterns on the head resemble the face-paint patterns worn by the Iatmul on important occasions. The chest is adorned with a series of crescent-shaped elements representing pearl-shell ornaments.

Iatmul Suspension Hooks (Samban)

Eric Kjellgren wrote: latmul suspension hooks (samban or or tshambwan) serve both utilitarian and ceremonial functions. 1 Suspended from the rafters by a cord tied through a hole in the upper portion of the object, samban are used to safeguard food, clothing, valuables, and other items, which are placed in baskets or string bags and hung from the hook-shaped prongs at the base to keep them out of the reach of rats and other vermin. In the past, and to a considerable extent today, samban are the primary means for storing important items both in ordinary dwellings and in men's ceremonial houses. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Although some examples are unadorned, the majority are carved with representations of the ancestral spirits and totemic animals associated with the owner 's clan. 4 In the present work a human head, likely representing a primordial ancestor, appears above the stylized head of a catfish (recognizable by its three sharp projecting spines), almost certainly a clan totem.

Suspension hooks also served as sacred images, through which the supernatural beings they represented could be consulted and presented with offerings. Some large examples, especially those representing powerful waken, the most important category of supernatural beings, may have been intended solely as ritual objects. In the past each of the most powerful waken had a human "attendant," through whom it communicated with the human world.

Before embarking on an attack on an enemy village or on a hunting expedition, men gathered in the ceremonial house to consult the appropriate waken. The rites centered on a large suspension hook, representing the waken, to which the men presented offerings of chickens, betel nut, or other items, which they hung from the suspension hook to activate the power of the spirit. After consuming the offerings, the attendant became possessed by the waken and fell into a trance, during which the spirit spoke through him, providing advice and counsel. 11 At times household samban were also occasionally used to contact the spirits regarding more minor matters.

A suspension hook in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made in Aibom village in the middle Sepik region by the Iatmul people in the 19th century. Fashioned from wood, it is 41 inches (104.1 centimeters) high.

Iatmul Crocodile Canoe Prow

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Crocodiles play a central role in latmul art and culture, where they are intimately connected with origin traditions, male initiation, clan affiliation, and, formerly, warfare.1 According to one latmul creation account, an ancestral crocodile was responsible for forming the dry land on which humans live. In the beginning the earth was covered by a primordial ocean, into whose depths the crocodile dived. Reaching the bottom, the crocodile brought up a load of mud on its back. When the animal surfaced, the mud became an island. from this island the land grew and became fixed, though it still rests on the back of the ancestral crocodile, whose occasional movements are the cause of earthquakes. Both now and in the past, the prows of virtually all sizable canoes are carved, as here, in the form of a crocodile. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

One Iatmul canoe prow in the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made in Mindimbit village in the middle Sepik region in the 19th-early 20th century. Made of wood, and shell, it is 71 inches (181.6 centimeters) long. The scale of present work indicates that it probably adorned a large war canoe. Capable of holding fifteen to twenty-five men, each war canoe belonged to men from a single lineage and had to be consecrated through a complex ritual dedicated to the first ancestor, Kwaguse, which primarily involved the nearly continuous singing of sacred songs over a period of several months.

At the climax of the rites, the massive canoe, hewn from a single tree trunk, was carried into the men's ceremonial house, and an area surrounding the canoe and part of the dancing ground was fenced off, creating an enclosure that only senior male elders were permitted to enter. The younger men gathered outside and pounded on the fence, armed with lengths of sugarcane and bamboo and with coconuts, which they threw over it. The young men stormed the fence four times, after which the founding ancestors, in the form of mannequins with heads made from overmodeled skulls, appeared from behind the fence. Manipulated by the older men inside, the figures danced along the top of the fence as a sign that the community had succeeded in summoning the ancestors to the rites. At the conclusion of the ritual, the fence was ceremonially destroyed and the ancestral spirits entered the canoe prow, endowing it with supernatural power that ensured success in warfare. These large canoes were also used for trading and fishing expeditions.6 Although such vessels are no longer employed in war, contemporary latmul artists continue to carve large canoes for use in trading expeditions and general transportation.

A centerpiece of the gallery for Melanesian art is a 14-foot-tall drum, or “slit gong,” carved from a massive tree trunk in the 1960s by an Ambrym islander named Tin Mweleun. Among the few pieces in the exhibition whose maker is known, it is in the traditional form of a figure with big, goggle eyes, braided hair, little arms and a hollowed-out, cylindrical body with a long, vertical slot cut into it. Struck with mallets by drummers, slit gongs make deep sonorous notes.

Because their sounds could carry great distances, they were used for communication as well as for dance music. and because the vertical slot was conceived as the figure’s mouth, the sounds it produced also were thought of as the voice of the divine. The Met’s slit gong is formally imposing, and, like many other works on view, it exudes a hair-raising pagan allure. It’s a breathtaking marriage of the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

Sacred Slit Gong (Waken)

Ken Johnson wrote in in the New York Times: A centerpiece of the Metropolitan Museum of Art gallery for Melanesian art is a 14-foot-tall drum, or “slit gong,” carved from a massive tree trunk in the 1960s by an Ambrym islander named Tin Mweleun. Among the few pieces in the exhibition whose maker is known, it is in the traditional form of a figure with big, goggle eyes, braided hair, little arms and a hollowed-out, cylindrical body with a long, vertical slot cut into it. Struck with mallets by drummers, slit gongs make deep sonorous notes. [Source: Ken Johnson, New York Times, November 16, 2007

Because their sounds could carry great distances, they were used for communication as well as for dance music. and because the vertical slot was conceived as the figure’s mouth, the sounds it produced also were thought of as the voice of the divine. The Met’s slit gong is formally imposing, and, like many other works on view, it exudes a hair-raising pagan allure. It’s a breathtaking marriage of the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: In many parts of New Guinea the sounds produced by certain types of musical instruments played during ceremonies are said to be the voices of supernatural beings. Among the Iatmul and other Sepik peoples, the most important musical instruments are sacred ftutes and slit gongs-percussion instruments carved from massive logs, hollowed out to create a resonating chamber with a narrow slitlike aperture, whose edges are struck with wood beaters to produce a deep, sonorous tone. The ends of Iatmul slit gongs are typically embellished with ornate finials depicting totemic animals or other clan emblems. Large slit gongs are a prominent feature of Iatmul men's ceremonial houses, where the are sometimes arranged in pairs running longitudinal I down the length of the earthen floor of the open understory of the structure. Played to accompany a variety of ritual performances and other events, such gongs, though used exclusively by men, are readily visible and relatively public obiects. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Men 's ceremonial houses (Nggaigo), however, often house, or housed, groups of sacred slit gongs reserved for secret ceremonies. Believed to be a manifestation of waken, the most powerful of all supernatural beings, such sacred slit gongs, also called waken, were kept, together with other sacred objects and musical instruments, within the enclosed upper story of the ceremonial house, concealed from the view of women and children.

The Sacred Slit Gong (Waken) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made of wood by the Iatmul people. Dated to the 19th century, it originates from Komindimbit (Kaminimbit) village in the Middle Sepik River and is 15.25 inches high, with a width of 12 feet nine inches and a depth of 18.5 inches (38.7 x 386.1 x 47 centimeters). This slit gong forms part of a complete ensemble of such sacred musical instruments, comprised of two slit gongs and two percussion planks (horizontal boardlike objects struck to produce a musical tone) now in the Museum's collection. All four are carved in the form of supernatural catfish (recognizable by the three spines that project from the back of the head) portrayed with long, crocodile-like jaws.

Such ensembles form, or formed, the central elements of an extensive secret ritual, also known as waken, performed only by senior male elders. During the rites the sacred slit-gong ensemble was played continuously day and night for periods as long as several months by relays of percussionists, each performer taking the moving drum beater from the hand of his predecessor so that the rhythm remained uninterrupted. When the slit gongs were being sounded, the community had to remain silent and people were forbidden to argue, shout, or even break firewood. At the conclusion of the rites the old men, impersonating the waken, emerged from the ceremonial house and danced before the village women. Although the slit drums were played continuously throughout the ceremony. the rhythm was rarely sustained unbroken for periods of more than two or three days.

Iatmal Pigment Bowls, Head Rests and Horns

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Pigment bowls — small oblong vessels that were used to mix and contain paint or, more rarel. other substances — were produced by a number of middle Sepik cultures.' Created in a variety of forms, these exquisitely crafted vessels were primarily employed to hold paints used to adorn the human body on important occasions. . Pigment bowls were rare and treasured objects, reported! by senior men, who passed them down as heirlooms to their successors. Among the latmul people, pigment bowls were formerly used to mix the supernaturally charged paint applied to the faces of warriors prior to combat. As the paint was being mixed, magical incantations were recited, endowing the warrior with the supernatural power to vanquish his enemies. The bowls were also employed to hold the paint used to adorn the faces of the overmodeled skulls of ancestors and enemies. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Pigment bowls were carved in a diversity of forms, including human figures, crocodiles, turtles, pigs, fish, and geometric compositions. One such bowl, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made Yentchanmangua village in middle Sepik region by the latmul people in the 19th century. Fashioned from wood, paint and fiber, it is 10 inches (26. 7 centimeters) long. Another from the same time and area is 7 inches (17.8 centimeters) long. The recumbent human figure in one of the examples, whose sharply flexed limbs grasp the outer edges of the bowl, represents a spirit or ancestor. The thin, elegantly curved bird head on the second example depict a hornbill, while the small lug on the opposite end possibly represents a crocodile, both of them species likely associated with the owner's clan. The figure's chin and the bird 's beak in the present examples are attached to the rim, while the neck is in each case carved free, creating a loop that may have allowed the vessels to be suspended when not in use.

Like many Pacific peoples, the Iatmul use wood headrests as pillows on which to rest the head or neck during sleep. One such headrest in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made in Aibom village in the middle Sepik region by the Iatmul people in the 19th century. Made of wood, shell, hair, fiber and paint and is 24 inches (61.9 centimeters) long. This work consists of a smooth central section that accommodates the user's head, flanked by carved finials.' The central portion is grasped by female figures whose tense limbs and arched backs make them appear almost to be pulling the ends of the headrest in opposite directions. Possibly representing a pair of legendary sisters from oral tradition, the figures have eyes inlaid with shell, heads crowned by coiffures made from locks of human hair, and bodies embellished with miniature versions of personal ornaments, including shell or fiber necklaces, bracelets, and anklets. In addition to functional examples, headrest-like objects, also called amba ragat, were used during male initiation. As an initiate lay prone, the amba ragat was pressed down on the nape of his neck, forcing his head to the ground as a reminder to the young man to keep his head down when lying in ambush for an enemy.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art contains horn made in Korewori River area in the late 19th-early 20th century. In former times, side blown trumpets, played by blowing while vibrating the lips into a hole on the side rather than the end of the instrument, were associated with warfare in the Middle Sepik Region of northeast New Guinea. Among the Iatmul people, side blown trumpets were sounded after a raid to announce the arrival of the warriors as they returned to their home village with prisoners or enemy heads. Like many Iatmul instruments, the trumpets were often played in pairs by two men, each using a trumpet with a slightly different pitch, who sounded them in alternation.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, William A. Lessa (1987), Jay Dobbin (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025