Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

EAST SEPIK PROVINCE

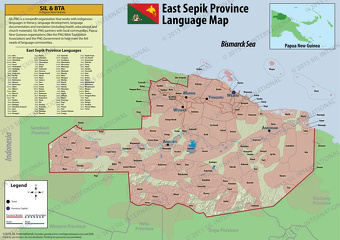

East Sepik is a province in Papua New Guinea. It had an estimated population of 450,530 people according to the 2011 census and covers 43,426 square kilometers (16,767 square miles size) — about 10 percent of Papua New Guinea. Its population in 2011 was 10.4 people per square kilometer. The province had a a population of over 389,000 and population rate of 2.2 percent according to the 2000 census. The coasts, the ranges and the foothill areas have higher population densities whilst most other areas, especially the Sepik plain, are sparsely populated. The Province has a young population with 44 percent under the age of 15 and 3 percent aged 65 years and over according to 2000 census data. [Source: Wikipedia; East Sepik Province government]

East Sepik Province extends for 190 kilometers (110 miles) along the northern coastline and borders Madang and Sandaun provinces near the coast and Western Highlands and Enga provinces in the central ranges. The Province includes the Sepik River basin and the off-lying islands of the Wewak and the Schouten Islands groups. East Sepik province's geography is dominated by the Sepik River, which is one of the largest rivers in the world in terms of water flow and is known for flooding. The river's level can change by as much as five metres in the course of the year as it rises and falls. The southern areas of the province are taken up by the Hunstein Range and other mountain ranges which form the central cordillera and feed the Sepik River. There are a scattering of islands off shore, and coastal ranges dominate the landscape just inland of the coast.

The East Sepik provincial government was created in 1976. Wewak, the provincial capital, is located on the coast of East Sepik. East Sepik province has six electorates with political representatives to the National Parliament. Each province in Papua New Guinea has one or more districts, and each district has one or more Local Level Government (LLG) areas. For census purposes, the LLG areas are subdivided into wards and those into census units. Access to service centers often requires 4 to 8 hours travelling time. The economy of East Sepik China- has improved thanks to cocoa and vanilla farming. The economy is set to improve further with the re-gravelling and paving of the national highway and investments in a tuna factory and cocoa production.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEPIK RIVER GROUPS: WHERE THEY LIVE, ART, SPIRIT HOUSES, CROCODILES ioa. factsanddetails.com

KWOMA (A SEPIK RIVER TRIBE): HISTORY, LIFE, ART ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE LOWER (EAST) SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ABELAM AND ARAPESH OF THE SEPIK RIVER: LIVES, HISTORY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE: MASKS, FIGURES AND SHELL RINGS ioa. factsanddetails.com

BIWAT (MUNDUGUMOR): LIFE, RELIGION, FAMILY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

IATMUL PEOPLE OF THE SEPIK RIVER: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHAMBRI: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CROCODILE MEN AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

WEST SEPIK HIGHLANDS PEOPLE — WAPI, TELEFOL, MIAN, GNAU, BIMIN — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

Yangoru Boiken

The Boiken are an ethnic group of Papua New Guinea’s East Sepik Province, with the Yangoru Boiken living primarily in the southern foothills of the Prince Alexander Mountains. Their homeland stretches from the islands of Walis, Tarawai, and Muschu in the Bismarck Sea, inland across the Prince Alexander Range, and down into the rolling grasslands north of the Sepik River. This territory—marked by striking ecological diversity—has contributed to significant cultural and linguistic variation within the group. [Source: Paul B. Roscoe, “Boiken,” Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Oceania, ed. Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Boikin are also known as the Nugum, Wianu and Yangoru. The name Boiken derives from a coastal village where early missionaries settled, while Yangoru refers to the area surrounding the Yangoru government station. Before European contact, the Boiken did not conceive of themselves as a single people; local groups identified instead as nina (“we all”) or tua (“people”).

Population and Language: The Boiken population was estimated at around 40,000 in 1980, including roughly 13,300 Yangoru Boiken — of whom about 9,600 resided in the Yangoru area. The 2020s estimate, according to the Joshua Project, is about 62,000. The Boiken speak a language of the Ndu family (Middle Sepik stock, Sepik–Ramu phylum). Linguistically, it forms a chain of related dialects rather than a single unified tongue. The Yangoru Boiken comprise one of seven dialect groups, with five distinct subdialects, each associated with subtle cultural differences. [Source: Wikipedia, Joshua Project]

History: Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that Boiken territory was once inhabited by speakers of Torricelli languages. Centuries ago, migrants speaking Ndu languages from the Koiwat region north of the Sepik River moved into the area, assimilating the Torricelli-speaking inhabitants. This dual ancestry—Ndu and Torricelli—helps explain cultural affinities between the Yangoru Boiken and their Torricelli-speaking neighbors, such as the Mountain Arapesh. Substantial European contact began in the early twentieth century, though it was not until the 1930s that missionaries, patrol officers, and labor recruiters had a pronounced impact. By then, steel tools had replaced stone, warfare was waning, and traditional initiation and artistic practices were beginning to decline. By 1980, male initiation and most ritual arts had disappeared, with currency replacing shell wealth and imported utensils displacing traditional wooden and clay items.

Yangoru Boiken Society Religion and Culture

Yangoru Boiken society is divided by sex and age, with middle-aged men dominating public life. The hring is the primary political unit, and villages are often divided into two moieties — Samawung (“Dark Pig”) and Lebuging (“Light Pig”) — which exchange pigs and yams in great ceremonial feasts.Leadership follows a big-man system, where influence is gained through generosity, success in exchanges, and oratory skill. Some women also gain prestige through their achievements in food production and wealth exchanges. Disputes are settled through moots (public discussions), though gossip and sorcery threats remain informal methods of social control. Prior to colonial pacification, warfare between rival confederacies was common, often over land, revenge, or abduction. [Source: Paul B. Roscoe, “Boiken,” Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Oceania, ed. Terence E. Hays, 1996]

According to the Joshua Project, approximately 99 percent of Boiken identify as Christian, with between 10 and 50 percent identifying as Evangelical. Traditional Yangoru Boiken cosmology distinguishes between what is “given” and what was created by cultural heroes. The world is populated by ancestral spirits and wala spirits, who exert powerful influence over human affairs. The wala include both great ancestral heroes—some now embodied in local mountains—and male and female spirits of the bush and streams.

Death is generally attributed to sorcery. The spirits of the dead are believed to linger near their hamlets before traveling to a sacred pool associated with their hring (lineage). Some are said to ascend Mount Hurun, where they join Walarurun, the great culture hero. Religious specialists, including sorcerers and magicians, were called upon to influence weather, health, and fertility. The most elaborate rituals once revolved around initiation, birth, marriage, and death, with the wala and pig exchanges serving as key ceremonial contexts. Since contact, the Yangoru Boiken have become known for several millenarian movements.

Traditional Boiken art included carved and painted decorations for spirit houses, wooden figures, shell and fiber masks, ornaments, and weapons incised with geometric patterns referred to as the “face of the wala.” Temporary masks and effigies were also created for specific ceremonies. Today, much of this art is no longer produced, though oral art—songs and oratory—remains vital. Yangoru Boiken ceremonial houses—often featuring towering triangular facades—resemble those of neighboring groups. These spirit houses (ka nimbia) are richly adorned with paintings that depict primordial beings or clan ancestors.

Yangoru Boiken "flute-playing" (hangwu) drum is carried by rattan shoulder strap running through the two lugs on the drums body. While beaten the drum, the drummer plays at the same time a bamboo trumpet that is Similar to the Australian didgeridoo. The drum has a wood skin traditionally carved with stone tools.

See Separate Article: ART FROM THE LOWER SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Yangoru Boiken Life, Family and Economic Activity

A distinctive aspect of Boiken material culture is the talipun, a traditional form of wealth and ceremonial currency. A talipun combines a carved or woven fiber mask with a large marine shell and serves as an important medium of exchange in bridewealth payments, compensations, and major ceremonies. [Source: Paul B. Roscoe, “Boiken,” Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Oceania, ed. Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Villages typically consist of fifteen to thirty-five hamlets, situated on forested ridges and housing 150–400 people. Each hamlet contains several houses belonging to one or two hring. Houses are either raised on stilts or built directly on the ground, with palm thatch roofing and sago-bark or cane walls.

Yangoru Boiken social life centers on the hring, a patrilineal descent group of about ten to fourteen members. Membership can also be obtained through long-term residence and participation in group obligations. Several hring form larger totemic or quasi-clan groupings that cooperate in exchanges and political affairs. Marriage is ideally between cross-cousins—though in practice, individual choice is common. Marriages are usually virilocal, with the bride moving to her husband’s settlement, and involve bridewealth payments in shell or talipun valuables. Once a wife has borne children, divorce is rare.

The Yangoru Boiken practice slash-and-burn horticulture, cultivating yams, taro, and sago as staples, supplemented by bananas, coconuts, greens, breadfruit, and sugarcane. Hunting and fishing were formerly important but have declined since World War II. Traditional trade linked mountain villages with coastal communities, exchanging pork, tobacco, and pottery for salt, shells, and piglets.

Sawiyano

The Sawiyano live in East Sepik Province Near the border between West Papua, Indonesia (formerly part of Irian Jaya) and Papua New Guinea. Also known as the Ama, they speak the Sawiyano language, w Which uses a Latin script with specific characters for certain sounds, and number around 1,500 people. Their primary religion is animism, which is the belief that natural objects have a spiritual essence. Their culture emphasizes respect for elders and traditional leaders. Content is often shared through oral traditions and community gatherings. [Source: Google AI]

The Sawiyano first came into sustained contact with outsiders during World War II. Elders still recount how terrifying it was when airplanes flew over their villages for the first time. Not long afterward, a few Sawiyano living near a tributary of the Sepik River encountered Japanese soldiers, marking their first direct contact with the outside world. Over time, the promise of steel tools—axes, machetes, knives, and matches—drew some men to nearby plantations, where they worked as cheap laborers in exchange for goods that transformed daily life. [Source: Tumbaba.org ]

In 1965, the Australian administration extended control into the area, suppressing intertribal warfare and cannibalism, jailing those who continued the practice. A small airstrip was cleared soon after, and the first missionary arrived in 1973. Two years later, Papua New Guinea achieved independence (1975), but by the early 1990s government officials had largely withdrawn from the region. A short-lived government school near the airstrip, along with missionary efforts, introduced literacy to a few Sawiyano men and women. Over the past fifty years, life has changed profoundly. Cannibalism disappeared, and tribal warfare subsided. Houses, once raised high on stilts for defense, are now built closer to the ground. Religious life has also diversified—some people follow Christianity, others adhere to traditional beliefs, and many combine elements of both.

Despite these changes, much of the ancestral culture (tumbuna ways) endures. Traditional crafts remain central to daily life: food is gathered much as it was half a century ago, and houses — though now occasionally built with nails — still rely on age-old construction techniques. The bilum, Papua New Guinea’s iconic woven bag, continues to be crafted by Sawiyano women using both natural fibers and modern threads, symbolizing a way of life that bridges old and new worlds.

The PhD thesis “We Came from This: Knowledge, Memory, Painting and "Play" in the Initiation Rituals of the Sawiyanō of Papua New Guinea” by Philip Guddemi (1992) centers on a male initiation cult, for which different ritual houses are built, then abandoned after a ritual cycle's completion. “The most important ritual house, the yafi-nu, figures in mythic origin. Awoufaiso, the creator, thought the world, and then a yafi-nu, into being. He then thought ancestral men into being from sago spathe paintings in the yafi-nu. When these men and their wives and children refused to eat of a feast he prepared, because as a 'playful trick' he had placed pig-excrement-like mushrooms above the good food, he cursed them with mortality and sexuality, yet enjoined them periodically to re-create the yafi-nu ritual house, and to paint, as he had done, sago spathe paintings within it. Initiation rituals within this house take place in these paintings' presence. Such rituals also involve ordeals like that Awoufaiso attempted: initiates are led to believe bad things will happen to them, then reassured and feasted. Initiates are 'grown' by older men's magical 'nurturance,' and are separated from women while, as transvestite dancers and subsistence producers, initiates appropriate female roles.” [Source: “Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin, January 2006; Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

Banaro

The Banaro people live along the middle course of the Keram River, a tributary of the Sepik River in Madang and East Sepik provinces. Also known as Banar and Banara, they are known for their complex social structure, which was studied in detail by anthropologists Richard Thurnwald in the early 20th century and Bernard Juillerat in the late 20th century, and are also noted for its use of communal houses and patrilineal clans. The Banaro have a rich spiritual life, with beliefs in ancestral ghosts and mischievous goblins, and historically relied on magic and persuasion to lead their society. Magic is considered a primary means of manipulating the natural and supernatural worlds. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Banaro population in the 2020s was 4,800 and 90 percent were Christians. Other estimates list their population at around 6,900 people. In the 1990s, it was estimated the Banaro numbered about 2,500.

Language: Banaro (also known as Waran) is a Papuan language isolate within the Ramu language group. It is notably distinct from other members of the family, sharing remarkably few cognates. The Ramu family, comprising around thirty languages spoken across northern Papua New Guinea, was first identified by John Z’graggen in 1971 and later linked to the Sepik languages by Donald Laycock in 1973. Linguist Malcolm Ross has since classified them as one branch of the Ramu–Lower Sepik language family. Although Z’graggen originally included the Yuat languages in this group, that classification is now considered doubtful. With no full grammar yet available for any Ramu language, this family remains among the least documented in the Sepik–Ramu basin. [Source: Wikipedia]

Banaro in 1913, photograph by Richard Thurnwald

In the 1990s, the Banaro population was concentrated in two villages; previously, they had lived in four, two on each side of the Keram River. Each village consists of several hamlets (three to six), and each hamlet contains three to eight multi-family houses along with a communal structure sometimes called the “goblin hall.” Their subsistence economy centers on sago processing, supplemented by the cultivation of taro, yams, bananas, and sugarcane, as well as fishing and the hunting or raising of pigs. Land is owned by sib groups, and the Banaro also produce their own pottery and use bows and arrows. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Banaro society is composed of several patriclans, each divided into two subclans, which in turn contain localized patrilineages. Marriage is ideally based on sister exchange between exogamous clans, though the final decision often lies with the woman and her mother. A bride-price is customary. The basic domestic unit consists of a group of brothers, their wives, and children living together in a communal house divided into family apartments.

The Banaro live in large communal houses divided into sections for coresident brothers and their families. Each hamlet is made up of a single patriclan, with the two halves of the communal house belonging to separate subclans. These subclans are totemic and exogamous—members must marry outside their group—and they maintain alliances with other subclans through wife exchange. Alliances between subclans are sustained through reciprocal wife exchanges and often initiated or maintained by older, influential men. These leaders, who act as mediators in disputes and guide economic and military matters, rule not by command but by persuasion. Their authority rests largely on their exclusive knowledge of magic, which serves as a source of influence and social power.

Boys and girls both undergo initiation, with the girls marrying shortly thereafter. According to “Growing Up Sexually”: Among the Banaro, boy’s initiation into sexual life is experienced at the conclusion of his initiatory rites, with “an elderly woman, ordinarily the wife of the mother’s goblin initiator”. Thurnwald (1921) relates that wedding customs and puberty rituals were intimately connected. Specifically, boys were allowed sexual intercourse only after the rites.. The initiation ceremony for girls included defloration by a man who plays the part of a spirit. [Source: Thurnwald (1916)“Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin, September 2004]

Murik

Murik in 1977 Open Edition Journal

The Murik live in the mangrove lagoons and sandbanks at the mouth of the Sepik River in the East Sepik Province. Also known as the Karau, Kaup, and Mayet, they engage in fishing and trading, and are recognized for their carving. They have long been central to regional exchange networks along the northern coast. While traditional customs remain strong, Murik society is increasingly shaped by the cash economy and Christianity. In recent years, they have engaged in dialogue on climate change and rising sea levels, given their vulnerable coastal environment. [Source: Kathleen Barlow, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Murik population in the 2020s was 5,800. Their main language is Murik (Papua New Guinea). Their villages — Kaup, Big Murik (Mayet), Darapap, Karau, and Mendam — are built on narrow sandbanks separating mangrove lakes from the open ocean. The region experiences a wet season (November–May) with strong northwesterly winds, heavy rain, and storms, and a dry season (June–October) marked by calmer seas and ideal travel conditions. Village populations range from 80 to 450, with an estimated 1,500 residents across all settlements in the 1990s, though many Murik live and work in towns such as Wewak.

Murik villages face the mangrove lakes and are built on stilts (1–2.5 meters high) to withstand flooding. Houses are often grouped by descent group, though coastal erosion and land scarcity have disrupted older layouts. Each village maintains large ceremonial houses (taab) for secret rituals and men’s houses (kamasaan) for public meetings and carving work. Women’s ritual houses (sambaan iron) are maintained by senior women. Men and women both fish; women also collect shellfish and weave baskets. Sago, their main starch, is acquired through trade with inland villages. Exchange of fish, baskets, carvings, and shells for pigs, garden produce, and betel nut is ongoing. Trade partnerships are often inherited and maintained over generations, extending along the Sepik coast and river. Today, the Murik increasingly participate in the cash economy, earning income from fish sales, tourism carvings, and remittances from relatives working in towns.

Murik language belongs to the Nor family of Non-Austronesian (Papuan) languages, closely related to Chambri, Karawari, Yimas, Angoram, and Kopar. Multilingualism is common — many Murik also speak neighboring languages and Tok Pisin (Melanesian Pidgin). Historically, children were sent to live with trade partners in other villages to learn their language and strengthen trade ties.

History: Archaeological and oral traditions suggest that the Murik Lakes formed when the Sepik River filled an inland sea roughly 1,000 years ago. Murik origin stories trace their migration from Moim, near Angoram, to the coast about 400 years ago. Along the way, they interacted with Austronesian island peoples, resulting in a blend of Papuan and Austronesian cultural traits. Historically, warfare and headhunting occurred with neighboring inland groups, often linked to the sago trade. Conflicts also arose over sexual jealousy or membership disputes.

The first recorded mention of the Murik dates to 1616, when they encountered a Dutch expedition led by Jacob le Maire. German colonial forces later surveyed the area, but plantation activity was limited. A Catholic mission was founded at Big Murik in 1913 by Father Joseph Schmidt (S.V.D.), and a Seventh-Day Adventist church followed in Darapap (1952). During World War II, the Murik Lakes were occupied by the Japanese and bombed by Allied forces, causing major casualties. Under Australian administration, education and wage labor expanded, and after independence, Michael Somare of Karau Village became Papua New Guinea’s first Prime Minister (1975).

Murik Religion and Culture

Today, Christianity — especially Catholicism and Seventh-Day Adventism — is widespread among the the Murik but many Murik practice syncretic forms of faith, blending Christian beliefs with traditional spirit practices. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 90 percent are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being to 10 to 50 percent.

Traditional Murik religion centers on a multitude of local spirits and ancestor beings that influence health, fortune, and social order. Spirits inhabit carved figures and masks, and both men’s and women’s secret societies perform ceremonies to maintain community vitality. Illness or misfortune is often interpreted as a sign of social imbalance or ancestral displeasure. Illness is interpreted as both social and physical in cause. Healers diagnose ailments by identifying social tensions or spiritual offenses, then prescribe herbal remedies, bloodletting, or ritual appeasement. Common ailments like malaria or headaches are treated with modern medicines such as aspirin, though traditional healing remains vital. [Source: Kathleen Barlow, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Murik Female figure, 19th to early 20th century, wood, human hair, conus and nassa shell, rattan, pigment, De Young Museum

Murik ritual life integrates carving, dance, and costume. Spirit figures and masks are used by men’s age grades during initiation and ceremonial displays. Women’s weaving and performance also carry symbolic weight, expressing themes of fertility, continuity, and ancestral connection. Murik men are noted for their distinctive wood carvings — canoes, paddles, masks, and human figures — often imbued with spiritual significance. Women are renowned for twill-plaited bags and baskets, whose intricate designs are owned by families or descent groups. These items play a key role in expressing status, identity, and lineage and are widely traded or sold at markets.

Murik Society and Family

Murik social life is structured around exchange, kinship, and ritual obligations. Leadership rests with the elders of descent groups, who control sacred regalia called suman — ornaments of shell, feathers, and fiber that symbolize peace and authority. Disputes are settled publicly, often through compensation in pigs or goods, and social harmony is maintained through gossip, joking, and mocking performances by designated partners. [Source: Kathleen Barlow, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Marriage is typically monogamous and exogamous, ideally between partners who are at least third cousins. Bride-service, where a man works for his wife’s family before establishing a household, is customary. Nuclear families are the primary domestic unit, but sibling cooperation in food production, trade, and childcare remains central. Inheritance follows a rule of primogeniture (favoring firstborns), though property and titles may pass through either maternal or paternal lines. Children are raised with an emphasis on independence and responsibility, and firstborns often assume leadership roles within sibling groups.

Kinship: Descent is ambilineal — traced through both male and female lines — and organized into named corporate groups linked to founding ancestors. Leadership within descent groups is expressed through ritual sponsorship, trade organization, and feast-giving. Land is categorized into village sites, coconut plantations, gardens, and mangroves, with fishing rights shared communally. Ownership and use are regulated by senior siblings, usually the eldest of the senior generation. Kinship terminology follows the Hawaiian system, in which all parental generation males are called “father” and all females “mother,” while all same-generation males and females are “brothers” and “sisters.”

Murik Adolescent Sexuality

According to Kathleen Barlow (1985), “Boy babies are often handled and stimulated sexually by their mothers while they are nursing…Their mothers tease them about their little penes and poke them playfully. When angry they threaten to cut them off or yell at the little boys for appearing before them naked. “Don’t stand there in the ay with the rope bobbing up and down!” “Get out of here before I cut off that little snake of yours!” [Source: Kathleen Barlow, “Learning Cultural Meanings through Social Relationships: An Ethnography of Childhood in Murik Society, Papua New Guinea” Ph.D. Dissertation. La Jolla: University of California, San Diego (1985); “Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin, February 2006; Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

Also, “Modesty in little girls of this age [toddlers] is encouraged but not enforced. They are usually naked until at least five or six years old, when their own increasing awareness of their difference from boys makes them willing to put on clothes. But women are embarrassed by little girls’ nakedness and try to teach them to cover their genitals with their hands or a piece of cloth when they are sitting in a group of people. Traditionally neither boys nor girls wore anything until they were initiated around the time of puberty. Grandmothers reluctantly put clothes on little girls, saying, “Now the white man has come and they have taught us this way. Before, not at all.”

Boy initiations include “beatings, penis bleeding, and other forms of hazing...Much of [the] teasing is flirtatious, and as brothers and sisters approach adolescence it is, unsurprisingly, about infatuations, flirtation, and sexual relationships”. “Because they understand the heavy responsibilities of marriage and family, parents are concerned about preventing their children from becoming sexually active and from marrying at a very young age”

“Children have an early, though non-participatory awareness that sexuality and fighting are associated in non-sibling cross-sex relationships. They are often present when their parents fight, and hear others predict that another child will soon be on the way…children develop an early awareness of sexuality as a strong impulse in everyone, male and female. There are joking relationships between certain categories of affines, and with classificatory mothers’ brothers and fathers’ sisters. The content of the joking is often explicitly sexual and children are taught to make the standard jokes even before they are aware of their meaning. Older people, particularly of grandparents and senior joking partners do not hesitate to describe sexual intercourse explicitly to children and watch them recoil in disgust or better yet learn to participate in the joking repartee that the subject inspires”.

Children are publicly shamed on occasion. “During adolescence boys and girls begin to explore the domain of sexual relationships”. “Marriage is accomplished when either the young man or woman fails to go back to his or her parents’ house in the morning, or when one of them moves his/her belongings to the other’s house. The parents’’ consent is then requested […]” (p. 149).

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025