Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

CHAMBRI

Chambri boys Paga Hill Eastates

The Chambri people live in the swampy, shallow Chambri Lakes region of the East Sepik province in middle Sepik River area of Papua New Guinea. Also known as Chambuli, they are recognized for their unique social structures and the prominent "crocodile scarification" ritual for men. Historically, their society was noted for its reversed gender roles, where women were the leaders and primary food providers, handling tasks like fishing, a model studied by cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, who called them the Tchambuli. [Source: Deborah Gewertz, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, Google AI]

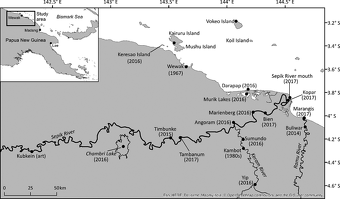

The Chambri live south of the Sepik River on an island Mountain in Chambri Lake in East Sepik Province of Papua New Guinea. Chambri Lake was created by the overflow of two of the Sepik's tributaries. This overflow occurs during the northwest monsoon season, from September to March, when rainfall nearly doubles in intensity from a dry-season average of 2.07 centimeters to an average of 3.72 centimeters per month. ~

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Chambri population in the 2020s was 4,700. Their main villages are Indingai, Wombun, and Kilimbit, with a combined population of approximately 2,900 people. In 1933, Mead reported that the Chambri population was approximately 500 people, but it is likely that this estimate was too low. It may well have excluded some 250 people: migrant laborers away on plantations, as well as their wives and children remaining on Chambri Island. In 1987, the total number of Chambri living on Chambri Island, and elsewhere in Papua New Guinea and beyond, was about 1,500. Of these, approximately one-half were living in the three contiguous home villages of Kilimbit, Indingai, and Wombun. The next-largest cluster of Chambri live in a settlement on the outskirts of the provincial capital of Wewak.

Language The Chambri people speak their own language, Chambri, which is a member of the Nor Pondo Family of Non-Austronesian languages and is related to Yimas, Karawari, Angoram, Murik, and Kopar.

Chambri History

Because the Chambri were a preliterate people, their early history can only be reconstructed through speculation and oral tradition. It is believed that their distant ancestors once lived in small, semi-sedentary hunting and gathering groups. Around a thousand years ago, these early Chambri likely united in response to the expansion of Ndu-speaking groups—particularly the ancestors of the Iatmul—and eventually settled in three villages along the shores of their fish-rich lake. [Source: Deborah Gewertz, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, Wikipedia]

Although geographically isolated, the Chambri established relationships with neighboring communities that encouraged cultural and economic exchange. Their most significant partners were the Iatmul people, with whom they developed a system of interdependence: the Chambri supplied fish in exchange for sago, and traded handmade tools and crafts for shell valuables. However, the arrival of Europeans and the introduction of metal tools disrupted this balance. As the Iatmul no longer needed Chambri tools, tensions rose, culminating in conflict that forced the Chambri to temporarily abandon their island. They returned in 1927 after peace was restored.

Chambri Lake is close to the Sepik River; it is a huge lake, where the waves can be dangerous for even large canoes; outriggers are not used on the lake

The first recorded contact between the Chambri and Australians occurred in the early 1920s, and by 1924 regular relations had been established. Labor migration to plantations began around 1927, further exposing the Chambri to outside influences. Anthropologists Margaret Mead and Reo Fortune conducted fieldwork among them in 1933, and in 1959 Catholic missionaries completed an elaborate church at Indingai village—the most prominent in the Middle Sepik region.

The Chambri have long been part of a complex regional trading network linking the peoples of the Sepik River, its tributaries, and the Sepik Hills. This network extends beyond the exchange of subsistence goods to include shared ceremonial traditions, connecting the Chambri to neighboring groups such as the Mali, Bisis, and Iatmul.

The Chambri were once known as fierce warriors and headhunters. Although they lived in relative peace with their neighbors, on occasion they were both perpetrators and victims of the head-hunting raids that were both sources and indicators of ritual power. The Chambri abandoned these practices after Papua New Guinea gained independence. Although European contact and missionary influence altered aspects of their material culture, the Chambri retained much of their social structure and interpersonal customs. Continued visits by anthropologists—including Mead, Deborah Gewertz, and Frederick Errington—brought new attention to their way of life. Some Chambri even traveled abroad to share their culture, returning with new ideas and perspectives. Despite economic challenges and the decline of traditional trade, the Chambri have endured. Their resilience and cultural pride have allowed them to adapt while maintaining the essence of their ancestral identity.

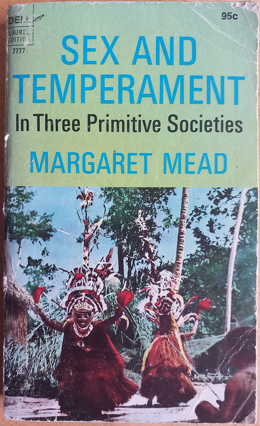

Margaret Mead and the Chambri

Margaret Mead studied the Chambri in the early 1930s along with two other Sepeik River tribes — the Abelam and Arapesh. Her influential book “Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies” became a major pillar of the women's liberation movement as it claimed that females had significant and dominant roles in Chambri society as breadwinners and leaders. [Source: Wikipedia]

After completing a field trip to Nebraska in 1930 to study the Omaha Native Americans, anthropologist Margaret Mead and her husband, Reo Fortune, traveled to the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea, where they conducted two years of fieldwork. During this period, Mead undertook pioneering research into gender and temperament, seeking to understand to what extent differences between men’s and women’s behavior were shaped by culture rather than biology. Her findings were first published in “Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies” (1935) and later expanded in Male and Female (1949). [Source: Library of Congress]

Mead observed strikingly different patterns of male and female behavior across the three societies she studied, each contrasting not only with one another but also with Western gender norms of the time. Among the Arapesh, both men and women were gentle, cooperative, and nurturing. Among the Mundugumor (now known as the Biwat), both sexes were aggressive, competitive, and assertive, striving for power and status. Among the Tchambuli (Chambri), gender roles were reversed from Western expectations: women were dominant, practical, and managerial, while men were more dependent and emotionally expressive.

These case studies formed the basis of Mead’s argument that gender roles are culturally constructed, not biologically fixed — a concept that became foundational in the social sciences. However, critics later contended that Mead’s interpretations were overly schematic, suggesting she may have emphasized cultural patterns that supported her theory while overlooking contradictory evidence.

In the later stages of their Sepik expedition, Mead and Fortune met the British anthropologist Gregory Bateson, who was conducting research among the Iatmul people. The three collaborated on developing a comparative framework linking culture and personality. Mead and Bateson shared both an intellectual partnership and a personal connection, which ultimately led Mead to divorce Fortune and marry Bateson, marking the beginning of one of anthropology’s most influential collaborations.

Mead and Fortune settled among the lake-dwelling Chambri in early 1933. They were led there by Gregory Bateson, who studied the nearby Middle Sepik culture of Iatmul. Mead wrote of the lake: “on its black polished surface, thousands of pink and white lotuses and blue water lilies are spread, and in the early morning white osprey and blue herons stand in the shallows.”

While Mead was not known for her linguistic abilities, her papers include notes she kept as she studied various languages in the field, as well as language notes made by others. Mead used a small notebook for recording vocabulary among the Chambri (Tchambuli). Mead wrote to anthropologist Clark Wissler (1870–1947), her department chairman at the American Museum of Natural History: “The language is the most difficult one we have struck.” The Chambri at this time numbered about 500 people, and their language was not understood outside the group.

In contrast to her studies of the Arapesh and Mundugumor cultures, which standardized the same personality for males and females, Mead found expectations of contrasting personalities for male and female among the Chambri, with the woman being dominant and the man responsive. At the time Mead and Fortune studied the Chambri, however, many of the men were away, which may have distorted Mead's conclusions.

Chambri Religion

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 70 percent of Chambri are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10-50 percent. Since the early 1960s, the Chambri have identified strongly as Catholics. Yet alongside their Christian faith, they continue to believe that all power—whether social, natural, or spiritual—derives from the ancestors. Religion, politics, and nearly all significant aspects of life revolve around invoking and embodying ancestral power, most often through the recitation of sacred, and often secret, ancestral names. Beyond the spirits of the dead, the Chambri recognize numerous autochthonous forces that inhabit the natural world—stones, whirlpools, trees, and, above all, crocodiles. These powers are thought to act independently but can also be influenced by those who know the proper rituals. [Source: Deborah Gewertz, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Religious Practioners: All adults possess some knowledge of powerful ancestral names, but the most influential men are those who know the greatest number. Knowledge of such names confers spiritual authority—and with it, the potential for sorcery. Some individuals, both men and women, are believed to be capable of spirit possession by ancestors from their maternal line, enabling them to diagnose illness, misfortune, or death. Others communicate with paternal spirits through dreams for the same purpose. Illness, according to Chambri belief, occurs when a person’s spiritual power has been depleted, often through sorcery or ancestral displeasure. Traditional healing practices aim to restore this lost vitality. Remedies may include compensating offended ancestors—sometimes through animal sacrifice—and applying or ingesting medicines imbued with ancestral power through incantation. Although the Chambri now have access to modern healthcare through mission and provincial hospitals, and a local aid post, Western medicine has not displaced traditional forms of diagnosis and treatment.

Ceremonies: Many Chambri ceremonies mark transitions in life, serving as rites of passage that integrate individuals more deeply into their patriclans. During these ceremonies, maternal relatives receive compensatory gifts recognizing their diminishing claim on the individual being initiated. The most dramatic of these rituals is male initiation, during which young men undergo hundreds of incisions on their backs, arms, and thighs—symbolically releasing the maternal blood that nurtured them in the womb (see Crocodile Men). Other clan-based ceremonies invoke ancestral powers to influence the natural world—ensuring the coming of the rains, the breeding of fish, or the fruiting of forest plants. Through these ritual obligations, a totemic division of labor arises in which each clan contributes to maintaining the balance and vitality of the universe.

Death and Afterlife: Chambri beliefs about the afterlife are fluid and sometimes contradictory. Spirits are variously said to ascend to the Christian heaven, remain in ancestral lands, or journey to a distant, unseen realm. Despite these differing views, the Chambri agree on one essential truth: the dead are never far away. The living and the spirits of the departed are believed to remain in constant interaction, each influencing the fate and fortune of the other.

Chambri Marriage

Chambri marriage traditionally involved the exchange of bride-wealth: shell valuables in the past and, more recently, cash. These prestations by the wife-takers are politically significant, serving as public demonstrations of clan wealth and prestige. In return, the wife-givers reciprocate with generous food offerings. Among non-Catholics, divorce can be initiated by either partner — often due to incompatibility or infertility — though it is discouraged by both families, since it requires the return of affinal payments. When divorce does occur, young children usually remain with their mothers until they are old enough to assume patrilineal responsibilities. [Source: Wikipedia; Deborah Gewertz, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Since the early 1960s, when the Catholic mission became firmly established in the region, polygyny among the Chambri has become increasingly rare. The preferred form of marriage remains mother’s brother’s daughter marriage, which reinforces kinship ties between clans. In the 1990s, about 30 percent of Chambri unions occurred between members of a matrilateral (mother’s side) cross-cousin’s clan. Although recent years have brought some changes, most marriages still occur within the village, and nearly all are between fellow Chambri. Because Chambri settlements are compact and closely connected, women who relocate to their husband’s clan land typically remain near their natal families.

Although Chambri society is patrilineal and marriages are often arranged, the process involves cooperation between both male and female relatives. Men commonly negotiate marriages that strengthen inter-clan alliances, but women also play an active role in selecting partners, preferring men who possess strong ancestral power. Bride price is a respected custom rather than a demeaning one; the shells used in these exchanges are deeply symbolic, representing feminine qualities such as fertility, menstruation, and the womb.

Within marriage, Chambri gender relations are marked by both cooperation and tension. Men, who guard secret ancestral names linked to spiritual power, often fear their wives might inadvertently—or intentionally—reveal them. This anxiety is heightened by women’s access to intimate substances such as their husbands’ hair, saliva, and semen, which could, in theory, be used by sorcerers. Yet this very fear is sometimes interpreted by men as a sign of status: if a wife covets her husband’s secret names, it is evidence of his power and importance. In this way, Chambri marriage reflects a balance between dependence and autonomy, tension and respect—a system where alliances, power, and gendered beliefs intertwine to sustain the fabric of community life.

Chambri Family

In the past, Chambri women lived together in large multi-family clan houses that symbolized both family unity and affinal (marital) interdependence. Each wife arranged her cooking hearth within the section of the house belonging to her husband and hung a carved hook displaying the totemic emblem of her own patriclan. From this hook, she suspended a basket containing part of her inheritance in shell valuables—objects of both economic and symbolic value.Today, influenced by Catholic teachings and the growing cash economy, these communal houses have largely been replaced by smaller, single-family dwellings. Clan members often prefer this arrangement, as it allows them to better safeguard privately purchased goods such as radios and tools from communal or patrilineal claims. [Source: Wikipedia; Deborah Gewertz, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Within traditional Chambri families, the relationship between brothers and sisters represents one of the most balanced and mutually supportive forms of gender interaction. Unlike the tension that sometimes exists between husbands and wives, fear and rivalry are absent in sibling relations. Brothers and sisters depend on one another: men rely on their sisters for political alliances and social support, while women depend on their brothers for assistance and protection, particularly concerning their children. A man plays an especially important role in the lives of his sister’s sons, who in turn often become instrumental in supporting their uncle’s political ambitions.

This reciprocal relationship between a maternal uncle and his nephew reflects a broader pattern of interdependence between matrilateral kin. The terms “brother” and “sister” are also used more broadly within the clan, extending beyond biological siblings to include members who act as kin during times of mourning or hardship. For women, the death of a clan member represents the loss of emotional support, whereas men experience it as the loss of a political ally within the community structure.

Child Rearing and Socialization: Mothers bear the main responsibility for raising and socializing young children, though they often entrust childcare to their sisters or other women when occupied with work—especially when fishing. Men are affectionate but seldom tasked with direct childcare, as contact with bodily waste is considered polluting. Among children, one of the most significant relationships is with the mother’s brother, who serves as both protector and mentor. When upset or in need of comfort, children often turn to these maternal uncles. The maternal uncle also plays a central role in his nephew’s initiation rituals, including the scarification ceremonies that mark the boy’s transition to manhood. Through this enduring bond between sisters’ sons and their maternal uncles, the Chambri reaffirm the strength of matrilateral ties within an otherwise patrilineal society.

Chambri Women

In her 1933 field research in Papua New Guinea, Margaret Mead observed the Chambri (then known as the Tchambuli) and proposed an interpretation of gender relations that challenged prevailing assumptions about male dominance across cultures. Mead suggested that, in Chambri society, women held a position of primary power and influence within the village—an inversion of what was then considered the global norm. [Source: Wikipedia]

Her conclusion was based largely on economic observations. Mead noted that Chambri women were the principal food providers, responsible for fishing — a task typically reserved for men in many other societies. Women not only caught fish to feed their families but also managed trade, carrying surplus catches into the surrounding hills to exchange for sago and other necessities. To Mead, this economic independence and control over essential resources indicated a matriarchal or female-dominant structure, where women’s contributions were central to communal survival.

Chambri women Remotelands travelogues

However, later anthropologists, including Deborah Gewertz and Frederick Errington, re-examined Mead’s findings and argued that her interpretation reflected a partial view of Chambri social life. While women indeed dominated in food production and trade, men retained authority in other critical spheres — particularly in politics, ritual life, and spiritual power. These domains were largely closed to women and formed the foundation of male influence within the community. Despite women’s prominent roles as providers and traders, marriages were typically arranged by men, reflecting the persistence of patriarchal organization in kinship and alliance-making. Yet, within these unions, men and women often interacted with the familiarity and cooperation of siblings, underscoring a deep-seated mutual dependence rather than submission or rivalry.

Gewertz and Errington concluded that neither men nor women were socially dominant over the other; rather, Chambri society operated on a complementary balance of power. Each gender held authority within distinct but interdependent domains. Men and women relied on one another economically, socially, and ritually, creating a system based not on hierarchy but on reciprocity. In this light, the Chambri illustrate how gender roles — and the balance of power between them — are shaped not by universal hierarchies but by local customs, economic organization, and cultural meaning.

Chambri Society

Chambri society is largely egalitarian, with all patricians—except those connected through marriage—considered potential equals. In affinal (marriage-based) relationships, however, wife givers are regarded as superior to wife takers, reflecting the value placed on marital exchange and alliance. Gender relations among the Chambri are also marked by relative equality, with men and women operating within largely autonomous spheres. The Chambri never developed a strong male-oriented military organization, in part because their position as valued producers and traders of specialized commodities shielded them from frequent warfare. Their emphasis on trade and exchange also discouraged male dominance, as control over women and their productive labor could not significantly increase the flow of valuables to men. [Source: Deborah Gewertz, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Kinship: The Chambri are divided into over thirty exogamous patricians (clans whose members must marry outside the group). These are further grouped into two overlapping systems—one affinal and the other initiatory—that together form partially cross-cutting patrimoieties. Each patrician is a landowning, residential, and ceremonial group, named after a founding ancestor. Members identify themselves as “people of the same totems,” highlighting their shared inheritance of totemic names, symbols, and powers.

All members of a patrician share collective responsibility for affinal debts—both the giving and receiving of payments associated with marriage exchanges. Through his own marriage(s) and those of his male relatives, a Chambri man becomes enmeshed in a complex web of reciprocal obligations that offer opportunities for political advancement. The competition to make impressive marriage payments drives men to demonstrate their equality—or superiority—to others in their ability to compensate wife givers. Those unable to compete effectively in these exchanges often become clients of more successful and influential men or patricians.

Chambri Kinship Terminology follows the Omaha system, which organizes relatives according to both descent and gender. In this system, an individual’s father and his brothers are referred to by a single term, as are the mother and her sisters. Marriages typically occur between members of different clans, reflecting the exogamous nature of the society. The

Property and Land —including fishing areas, ritual prerogatives, sacred objects, and inherited powers — are inherited patrilineally, passing through the male line. Women gain access to fishing areas through their husbands, though it is not uncommon for individuals to obtain temporary use of resources belonging to their maternal kin.

Social Control among the Chambri was historically maintained through violence or threats of violence, often tied to fears of sorcery or acts of raiding. Disputes were typically resolved through debate in men’s houses, where leaders and elders reached settlements. Today, the Chambri also use the formal judicial system of Papua New Guinea, including local and regional courts. Since Papua New Guinea’s independence in 1975, the Chambri have also engaged in modern political life, participating in local, regional, provincial, and national elections and sometimes providing their own candidates. For Chambri residing in Wewak, the police are sometimes called in to help manage conflicts. In most cases, after police involvement, disputes are resolved through a community meeting, followed by payment of damages and a ceremony of reconciliation to restore social harmony.

Chambri Villages, Life and Art

The Chambri have traditionally lived in three main villages — Kilimbit, Indingai, and Wombun — which stretch along the shores of Chambri Island in the Middle Sepik. In the 1990s, each village had a population ranging from 250 to 350 people. At that time every village maintained around five men’s houses, though at any given time some might stand only as sacred sites rather than active buildings. Traditionally, women who married into a clan lived in large multifamily houses, each household organized around the husband’s lineage. Today, these have largely given way to smaller family dwellings. Many Chambri now reside in Wewak, the capital of East Sepik province, where they live in a crowded squatter settlement composed of small houses made from bush or scavenged materials. The social layout of the settlement mirrors that of Chambri Island, with migrants from Kilimbit, Indingai, and Wombun living in their own respective sections.

Finial ornament with human figure surmounted by a totemic bird from the Chambri Lakes area, Aibom Village, Aibom People, red clay with white pigment

In their ideal form, Chambri men’s houses are impressive two-story structures with high gabled ends, carved finials, large oval second-story windows, and elaborately carved and painted interior posts. Perched at the physical and spiritual center of a settlement, these Haus Tambaran serve as the core of male ritual life. It is where men debate clan matters, prepare for ceremonies, and commune with ancestral spirits. Only men are allowed inside. Membership in a men’s house is patrilineally inherited, including men from several related patricians. [Source: Deborah Gewertz, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Chambri diet continues to center on fish and sago. Fish are caught in the lake waters surrounding the island, while sago is acquired from the Sepik Hills, either through barter or purchase. The Chambri supplement their staple diet with greens, fruits, and cultivated crops such as watermelons, yams, beans, and vegetables grown on the exposed lakebed during the dry season. Chickens and ducks are common household animals—far more so than pigs.

Chambri women are primarily responsible for fishing, marketing, and food preparation. Men handle house building, canoe making, carving, and ritual duties. In the past, warfare and the production and trade of stone tools were also important male occupations.

Chambri art is a vivid expression of ancestral identity and clan heritage. Whether seen in drums, masks, carved house timbers, or decorated suspension hooks, each form embodies the presence and power of ancestors or references clan-based claims to those powers. Traditional Chambri artworks often feature a minimal color palette of black, white, and red, emphasizing bold contrast and spiritual potency. In modern contexts, similar designs are created for sale to outsiders, preserving aesthetic traditions even as their ritual significance fades.

Chambri Economic Activity

Chambri women traditionally have conducted the fish-for-sago trade, traveling to barter markets held on a six-day cycle in the surrounding hills. These markets bring together Chambri women and others from neighboring highland villages. Unlike their historical trade relationship with the Iatmul — once marked by tension — today these exchanges are conducted on a basis of relative equality.

Fish-for-sago barter markets remain a defining feature of Chambri economic life, complemented by cash markets held twice a week on Chambri Island where food and other goods can be purchased, In the late 1980s, roughly 15 percent of the Chambri’s sago was still obtained through barter, though cash income had become increasingly important. Principal sources of money now include the sale of smoked fish to migrant laborers in town and the sale of carvings and woven goods to art dealers and tourists.

Before European contact, the Chambri were renowned producers of specialized goods used throughout the Middle Sepik region. Women wove large mosquito bags from rattan and reeds, while men quarried and shaped stone tools from Chambri Mountain for regional exchange. Today, both men and women continue to produce for the tourist trade, with women weaving finely crafted reed baskets and men carving wooden figures, masks, and hooks inspired by traditional ritual designs. While these carvings retain ancestral motifs, they are no longer imbued with sacred power, having shifted into the realm of art and commerce.

Chambri Crocodile Men Initiation

In Chambri cosmology, the crocodile — or pukpuk in Tok Pisin — is more than a powerful river creature; it is an ancestor and creator being. Two myths explain the tribe’s origins. In one, a young girl is carried into the river by a crocodile and later gives birth to the first crocodile people. In another, men once lived among crocodiles to learn their secrets and were eventually transformed by that sacred power. Because of this ancestral link, the crocodile symbolizes strength, protection, and transformation. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The Crocodile Men initiation — one of the most striking coming-of-age rituals in Papua New Guinea — honors this spirit, marking the passage from childhood to manhood through pain, sacrifice, and rebirth. The scarification ritual forms the heart of the ceremony. Deep cuts are made across the chest, back, and buttocks of initiates, creating patterns that resemble the scales of a crocodile’s hide. The scars are not merely decorative — they represent a symbolic shedding of the mother’s blood, separating the boy from the world of women and infusing him with the strength of the crocodile spirit.

Known locally as the Wagan (or Wakan) ceremony, the ritual is also a celebration of ancestral return. To endure the ordeal without showing weakness is to prove one’s courage, discipline, and worthiness as a man. The resulting scars become permanent badges of honor and spiritual connection.

Initiation begins long before the first cut. For two months prior, the young men live in seclusion within the Haus Tambaran — or Spirit House — a sacred men’s house found in every Chambri village. During this period of seclusion, maternal and paternal uncles instruct the initiates in clan genealogies, sacred chants, and mythic lore. Whispered lessons reveal the tribe’s most closely guarded secrets — an education that binds each initiate to his lineage and prepares him for the responsibilities of adulthood.

The initiates must also submit to strict rules of sacrifice and discipline. They live on a restricted diet of fish, sago, and greens, prepared only by men. They must not speak to or look at women — who are believed to possess powers that can weaken or “unmake” a man. They are forbidden to wear shoes, smoke, chew betel nut, or engage in any pleasure. Even mealtimes are conducted in silence, facing the wall. If an initiate breaks these taboos, he is punished by the elders. The process teaches self-control, humility, and endurance, all considered essential virtues of manhood.

Chambri Crocodile Men Initiation Ceremony

The night before the ceremony is one of exhaustion and heightened emotion. The initiates sing and dance throughout the day and night, chewing ginger roots to dull their senses. At dusk, they are led into the jungle, each accompanied by a male guardian who escorts him on brief visits to friends and relatives. There is no sleep that night — only ritual movement and anticipation. As dawn breaks, they are taken to the Blackwater River to soak for over an hour. The purpose is twofold: to harden their resolve and to soften the skin for cutting. Emerging from the river, the young men are ready to face the ordeal that will transform them. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Inside the Spirit House, banana leaves are spread across the floor. Each initiate lies down, cradled by his maternal uncle — the man who will “return the mother’s blood” by overseeing the cutting. Traditionally, this act symbolized the uncle giving his sister’s child back to the men’s world. A professional cutter performs the scarification using blades — once sharpened bamboo, now replaced with disposable razors to prevent disease. No anesthesia is used, save for a leaf chewed to distract from the pain. Over the course of an hour, more than a thousand cuts are etched into each man’s skin — first on the chest, then across the back and glutes. Each mark follows a precise pattern that, once healed, forms the body of the crocodile: 1) The eyes are cut around the nipples; 2) The nostrils along the abdomen; 3) The legs and tail carved into the back

As they emerge from the Spirit House to have their backs cut, they are greeted by friends and family chanting encouragement. Pain is seen as the crucible through which a boy is reborn as a man. After the cutting, the initiates are taken back inside to rest. Fires are lit to keep the air hot and dry. A special mixture of river mud and oil from the Kaumever tree is applied with a feather to encourage controlled infection — the swelling and raised keloids that give the scars their distinctive crocodile texture. The wounds are carefully tended over several days as the initiates recover, enduring the heat and pain in silence. The process is dangerous; infections sometimes prove fatal. But the scars that remain are considered a mark of spiritual rebirth and ancestral power.

A week later, the young men are brought before the community in a graduation ceremony. They are honored by elders and kin, praised for their strength, endurance, and courage. The scars glisten under the sun — a visible testament to their transformation. In the eyes of the Chambri, these men are no longer boys. They are Crocodile Men, bonded to their ancestors and to one another through suffering, courage, and shared initiation. The ritual remains one of the most powerful and painful rites of passage still practiced in the world today.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025