Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

BIWAT (MUNDUGUMOR)

The Biwat live in the area of the central Yuat River in East Sepik Province. Also known as the Mundugumor and Mundokuma, they speak the Biwat (Mundugumor) language and Melanesian Pidgin. "Mundugumor" is an old name relating to their art styles. The Biwat refer to themselves as "Biwats," the name of one of their villages as well as the name sometimes given to the Yuat River. The Biwat language belongs to the Yuat family.[Source: Joshua Project; Wikipedia]

The dominant geographical feature of the region where Biwat live is the Sepik River, which winds from the interior mountains through the hills, swamps, and grassland plains of the province. One of its principal tributaries is the Yuat River, a swift and strongly currented waterway that floods periodically. While swamps and grasslands predominate to the north and south, the Biwat territory also includes areas of rainforest. The climate is tropical, with a rainy season extending approximately from November to March. [Source: Nancy McDowell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Biwat population in the 2020s was 5,700. Early in the 20th century, the Biwat population was estimated at roughly 1,000 people, sustained by ample land and environmental resources. Since then, population growth has produced increasing land and resource pressures. Many Biwat now migrate for wage employment in towns and cities or participate in resettlement schemes in nearby areas such as Angoram.

History: Little is known of Biwat history prior to European contact. Oral traditions suggest that the villages were founded by migrants from the west. A major historical event was the alteration of the Yuat River’s course, which left two villages inland (“in the bush”) and converted the other four into riverine settlements. Conflict was frequent in precolonial times, both within and between villages. Disputes arose over marriage exchanges, adultery, and reputation, while warfare and raiding sought to avenge insults and affirm prestige. Inter-village alliances were unstable and shifting, shaped by the ever-changing balance of power and kinship ties.

Western contact began in the early 20th century through German and Australian traders, administrators, and missionaries. As a result, warfare, raiding, and many ceremonial practices ceased, and men began working for extended periods on coastal plantations. Although a permanent mission station with an airstrip and resident priest was not established until 1956, missionary influence was already strong. Today, a school in Biwat village serves the area, and many young people pursue further education and skilled or professional employment in urban centers.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEPIK RIVER GROUPS: WHERE THEY LIVE, ART, SPIRIT HOUSES, CROCODILES ioa. factsanddetails.com

KWOMA (A SEPIK RIVER TRIBE): HISTORY, LIFE, ART ioa. factsanddetails.com

EAST (LOWER) SEPIK PEOPLE — BOIKEN, MURIK, SAWIYANO — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE LOWER (EAST) SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ABELAM AND ARAPESH OF THE SEPIK RIVER: LIVES, HISTORY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE: MASKS, FIGURES AND SHELL RINGS ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

IATMUL PEOPLE OF THE SEPIK RIVER: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHAMBRI: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CROCODILE MEN AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

WEST SEPIK HIGHLANDS PEOPLE — WAPI, TELEFOL, MIAN, GNAU, BIMIN — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

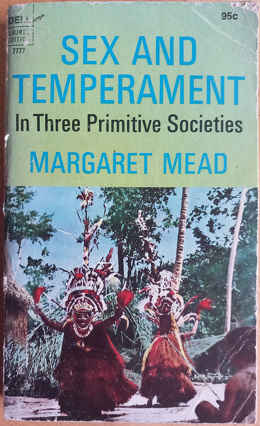

Margaret Mead and the Biwat

After completing a field trip to Nebraska in 1930 to study the Omaha Native Americans, anthropologist Margaret Mead and her husband, Reo Fortune, traveled to the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea, where they conducted two years of fieldwork. During this period, Mead undertook pioneering research into gender and temperament, seeking to understand to what extent differences between men’s and women’s behavior were shaped by culture rather than biology. Her findings were first published in “Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies” (1935) and later expanded in “Male and Female” (1949). [Source: Library of Congress]

Mead observed strikingly different patterns of male and female behavior across the three societies she studied, each contrasting not only with one another but also with Western gender norms of the time. Among the Arapesh, both men and women were gentle, cooperative, and nurturing. Among the Mundugumor ( Biwat), both sexes were aggressive, competitive, and assertive, striving for power and status. Among the Tchambuli (now the Chambri), gender roles were reversed from Western expectations: women were dominant, practical, and managerial, while men were more dependent and emotionally expressive. These case studies formed the basis of Mead’s argument that gender roles are culturally constructed, not biologically fixed — a concept that became foundational in the social sciences. However, critics later contended that Mead’s interpretations were overly schematic, suggesting she may have emphasized cultural patterns that supported her theory while overlooking contradictory evidence.

When Mead and Fortune left the Arapesh, they looked for a culture without much Western cultural contact and which was not the province of any other anthropologist. They settled on the Mundugumor (now Biwat), along the Yuat River in what is now Papua New Guinea. There they encountered an aggressive culture in a land plagued by ferocious mosquitoes. They stayed only three months. Mead's most prominent theory about the Mundugumor is the “rope” kinship system, which has been debated by later anthropologists. These paintings are among those Mead collected from the Mundugumor.

The Biwat were first studied in depth by Mead, who called them the Mundugumor, during her 1931–1933 fieldwork. Their second major field site in the Sepik River region of New Guinea was a Biwat community, which, until only a few years earlier, had lived largely beyond colonial control and maintained social systems centered on warfare, headhunting, and cannibalism. With this in mind, Mead portrayed the Biwat as overtly masculine, aggressive, and competitive, emphasizing traits such as virility, jealousy, and dominance. She observed that gender relations and parenting among the Biwat were deeply shaped by these values, and that women’s experiences of marriage and motherhood reflected the wider ethos of discipline and control that permeated Biwat life. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the later stages of their Sepik expedition, Mead and Fortune met the British anthropologist Gregory Bateson, who was conducting research among the Iatmul people. The three collaborated on developing a comparative framework linking culture and personality. Mead and Bateson shared both an intellectual partnership and a personal connection, which ultimately led Mead to divorce Fortune and marry Bateson, marking the beginning of one of anthropology’s most influential collaborations.

When Mead revisited the Biwat in 1971, she initially believed little had changed. However, prompted by anthropologist Nancy McDowell, she began a more comprehensive reassessment. After Mead’s death in 1978, McDowell completed the study, publishing “The Mundugumor: From the Field Notes of Margaret Mead and Reo Fortune” in 1991. By then, Biwat society had transformed dramatically. The “rope” system and many traditional kinship terms had vanished, replaced by Melanesian Pidgin and Christian influence. Most Biwat were now Catholic, with access to education and modern livelihoods. McDowell herself described the Biwat she met in 1981 as “warm, open, and generous, as well as assertive and volatile.”

The Yuat River remained the community’s lifeline, now navigated by motorized canoes linking the Biwat to markets in Angoram, Wewak, and Madang. While slash-and-burn horticulture continued, cash cropping of tobacco and betel nut had become central, alongside the raising of pigs and cattle. McDowell’s reexamination of Mead and Fortune’s field notes revealed them to be exceptionally detailed and professional, allowing her to reinterpret Biwat kinship and culture more charitably and to reconstruct the general ethnography Mead had envisioned half a century earlier.

Biwat Religion

According to the Joshua Project, approximately 90 percent of Biwat identify as Christian, primarily Catholic, with an estimated 10–50 percent identifying as Evangelical. Prior to conversion, the Biwat recognized numerous unseen but manipulable spiritual forces. Religious life centered on attempts to influence these powers through ritual and magic. The Biwat pantheon was relatively simple, featuring water and bush spirits associated with particular tracts of land, as well as ancestral spirits of the dead. Some mythical figures were believed capable of tapping directly into the universe’s inherent, unnamed powers. [Source: Nancy McDowell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Death was typically attributed to sorcery unless a natural cause was evident. After death, part of a person’s nonphysical essence became a ghost, inhabiting areas associated with the patrilineal clan. Mortuary rituals ensured care for the body and released the ghost from the village.

Curing rituals sought to identify the cause of illness—sorcery, soul loss, or taboo violation—and to restore balance through ritual acts and magical remedies. Religious specialists included curers, diviners, and ritual practitioners, though these roles were neither formalized nor hereditary. Individuals could own—by inheritance or purchase—spells, charms, and other means of control over supernatural forces. Ceremonial life included gardening rites (particularly for the long yam), life-crisis rituals, and initiation ceremonies in which young men, and occasionally women, were admitted to view sacred objects, each requiring a distinct initiation.

Biwat Marriage

Complex, competitive, and highly regulated, marriage formed the foundation of Biwat social organization, structuring both household life and long-term exchange relations. It was typically arranged through reciprocal sister exchange, in which a man acquired a wife by offering his own sister to another man. This system created strong bonds between fathers and daughters and between mothers and sons, but brothers and sisters were expected to avoid direct communication, viewing one another primarily as instruments of exchange. Men guarded their sisters’ marriage rights closely, sometimes competing with their own fathers or brothers for control.. [Source: Nancy McDowell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996' Wikipedia]

Ideally, Biwat marriages occurred between classificatory cross-cousins (the children of a brother and a sister), Men were prohibited from marrying women from their own clan or from their father’s clan, though these restrictions were often ignored. Marriage was valued less for companionship than for labor, fertility, and prestige, often generating conflict and jealousy between spouses.

Occasionally, marriages were secured by bride payment rather than exchange, often involving less-desired women or socially powerful men. Some leaders attracted wives without compensation, and women captured in raids were rarely reciprocated. Residence was typically patrivirilocal—wives joining their husband’s community—but a man who had not reciprocated a sister might be expected to live and work with his wife’s kin. Early marriages were often unstable, but stability increased after the birth of children. Polygyny was an admired ideal, though only prominent men could maintain multiple wives.

Despite the dominance of arranged marriage, love affairs and elopements were common, often accompanied by secrecy and violence. Encounters occurred in the forest, involving rough physicality that expressed passion and aggression.Men were more likely than women to engage in extramarital affairs, and many young girls’ first lovers were married men. Roughly one-third of Biwat marriages reportedly began as elopements, frequently leading to violent confrontation between the couple and the woman’s kin. Compensation—either a sacred flute or another woman—was often demanded afterward to settle the dispute.

Biwat Arranged Marriages, Virginity and Polygany

Most Biwat marriages were arranged, typically involving close family negotiation and mutual consent among kin groups. The brother–sister exchange formed the cornerstone of this institution, granting brothers significant authority over their sisters’ marital fates. In some cases, a sacred flute could be substituted as bridewealth, symbolizing purity and virginity. Men without sisters had to obtain wives through force or elopement, and families with many sons but few daughters faced chronic rivalry and violence.

Arranged unions could occur between very young adolescents, sometimes even before puberty. Girls were often sent to live with their betrothed husband’s family, which served both to secure the alliance and to prevent scandal if she later eloped. In such households, tensions frequently arose—girls might become objects of desire for the husband’s father or brothers, occasionally sparking violent competition. Virginity was highly prized, especially for exchange marriages; only virgins could be exchanged for virgins. Consequently, women who lost their virginity outside marriage saw their value reduced in marital negotiations.

Polygyny was the social ideal and both a status symbol and a source of tension. A successful man might have up to ten wives. Polygyny was Fathers and sons often competed for the same women, and older wives resented the acquisition of younger co-wives. Mothers, preferring to advance their sons’ prospects, frequently encouraged their husbands to exchange daughters for their sons’ future wives. Domestic conflicts were common, and defiant wives risked physical punishment.

Biwat Family and Childrearing

Household composition varied. Ordinary men’s households usually included one or two wives and their children in a single dwelling. Leaders’ hamlets often had separate houses for each wife, one for adolescent sons, and another for the head of household. Each wife maintained her own hearth and cooked separately, though senior wives might cook for all the husband’s children. [Source: Nancy McDowell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

For Biwat women, motherhood was demanding and ambivalent. Pregnancy was met with anxiety rather than celebration. Husbands sometimes reacted with anger, fearing loss of sexual freedom or suspecting infidelity. Intercourse during pregnancy was taboo, believed to cause twins, and women risked desertion if they conceived too soon. Infanticide was practiced under certain conditions, particularly when a child’s paternity was in doubt or when the family preferred daughters for marital exchange. Unwanted infants were often strangled or cast into the Yuat River. Newborns who survived were treated with pragmatic detachment. Mothers resumed work quickly, while fathers rarely interacted with their children. Feeding was mechanical — breastfeeding occurred standing up, with minimal tenderness. Infants learned early to struggle for sustenance, a pattern Mead interpreted as the origins of competitive behavior in Biwat culture. Children were encouraged toward independence as soon as they could walk, and mothers showed little overt affection, often laughing at their children’s fears or tears. [Source: Wikipedia]

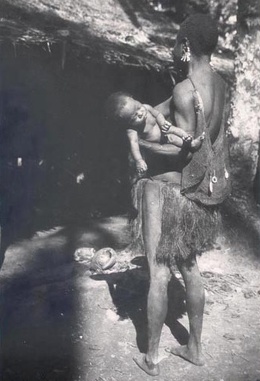

Mead reported that both Arapesh and Biwat mothers carried their babies suspended from their foreheads. While Arapesh generally women used net bags, which simulated the experience of the womb, Mead reported that the Biwat carried their babies in rough-plaited, rigid baskets. Older Biwat children would be carried on their mothers' backs with no support, holding on by grabbing the mother's hair. [Source: Library of Congress]

Inheritance was largely patrilineal with respect to land, but movable goods and ritual rights often passed to a man’s sister’s children, perpetuating bonds across generations. Before colonial control, Biwat families even exchanged their own children—usually sons—as hostages in trade alliances, demonstrating the transactional nature of kinship and the limited emotional value attached to children. Children were cared for but not indulged. Both parents viewed pregnancy and childcare taboos as burdensome, and childrearing emphasized toughness and independence rather than affection. Boys and girls alike grew up assertive and self-reliant.

Biwat Society and Kinship

Biwat society was organized into patrilineal clans, loosely tied to particular tracts of land. Marriage organization fostered gendered loyalties — sons to their mothers, daughters to their fathers. However, actual social and economic life was based on broad kin networks, including affinal and matrilateral ties. These connections underpinned generations of exchange transactions, metaphorically described by anthropologist Margaret Mead as “ropes”—a series of reciprocal exchanges initiated by one marriage and extending through several generations. [Source: Nancy McDowell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Biwat kinship was structured around a dual “rope” system: A male rope linked a man, his daughters, and his daughters’ sons’ daughters. A female rope connected a woman, her sons, and her sons’ daughters’ descendants. Land tenure was flexible. Land was nominally controlled by patrilineal groups, but individuals could use land belonging to any friendly relative, and requests for access were rarely refused.

Kinship terminology combined Hawaiian and Iroquois features. In the Hawaiian pattern, relatives of the parental generation were grouped as “Mother” or “Father,” and cousins were referred to as “Brother” or “Sister.” In the Iroquois pattern, distinctions were made between same-sex and cross-sex parental siblings: the father’s sister and the mother’s brother were labeled separately as “Aunt” and “Uncle.” Parallel cousins (children of same-sex siblings) were classified as siblings, while cross cousins (children of a brother and sister) were potential marriage partners.

Social life was anchored more in networks of kin than in rigid clan structures. Alliances were fluid and often shifted with circumstance. Leadership was achieved, not inherited, and depended on personal prowess in warfare, oratory, and exchange. Successful leaders—those able to attract followers—amassed wives, wealth, and supporters through strategic generosity. Social control was maintained through a combination of coercion, kinship obligations, and egalitarian norms that discouraged the consolidation of power. Strongmen who violated community expectations risked losing their followers. In contemporary times, Biwat communities participate in Papua New Guinea’s parliamentary democracy, electing representatives to local and national offices. Although traditional war leaders have disappeared, individuals excelling in education, business, or community affairs now hold influence.

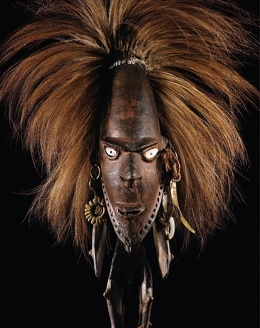

Biwat Art

The Biwat live in the area of the central Yuat River in East Sepik Province. Also known as the Mundugumor and Mundokuma, they speak the Biwat (Mundugumor) language and Melanesian Pidgin. "Mundugumor" is an old name relating to their art styles. The Biwat refer to themselves as "Biwats," the name of one of their villages as well as the name sometimes given to the Yuat River. The Biwat language belongs to the Yuat family.[Source: Joshua Project; Wikipedia]

Biwat art was primarily sacred in purpose, aiming to influence supernatural forces. Sculpture and painting predominated, showing stylistic influence from the Middle Sepik artistic tradition.Eric Kjellgren wrote: Biwat art is particularly remarkable for the delicacy and virtuosity of its intimately scaled wood carving-primarily personal ornaments worn in the hair or attached to the belts and armbands of dancers. Likely worn as an element of festive or ceremonial attire, this hair ornament has an unadorned, pinlike base, which would have been inserted into the wearer 's coiffure. Some sources, however, state that such hair ornaments were intended not to adorn the human head but rather to be inserted among the ornaments that decorated the heads of flute-stopper figures. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

One Biwat hair ornament in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection comes from the Yuat River area of the lower Sepik region. Dated to the late 19th-early 20th century, it is made of wood, paint and is 15 inches (40.3 centimeters) tall. Many Biwat ornaments were used interchangeably to adorn flute stoppers or the human body, so it is possible that the hair ornaments served both functions. Nonetheless, the size of the surviving hair ornaments, often nearly as tall as the flute stoppers themselves, suggests that they served primarily for personal adornment. The form of Biwat hair ornaments, whose central elements are encompassed within a series of concentric hooks, is strikingly similar to that of the larger hook images produced by the Yimam people of the Korewori River, whose headwaters lie nearby, as well as those of the more distant Bahinemo people..

The peoples of the Sepik are linked by an elaborate network of exchange in which songs, ceremonies, and ceremonial objects circulate widely. Thus, it is possible that the diminutive hook figures on Biwat hairpins were inspired by Yimam objects-such as the smaller hook figures used by Yimam men as hunting charms-obtained through trade.

See Separate Article: ART FROM THE LOWER SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Biwat Life, Villages and Economic Activity

Traditionally, the Biwat comprised six villages—four located along the Yuat River and two inland. Populations ranged between 100 and 200 people per village. Settlements were dispersed clusters of hamlets rather than compact nucleated villages, and lacked central plazas or permanent men’s houses. Today, the four river villages have expanded and nearly merged, though traditional architecture persists. Houses, built of sago ribs, palm bark, and hardwood posts, stood about 1.5 meters above ground, with some families constructing temporary shelters near distant gardens. [Source: Nancy McDowell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Biwat traditional economy centered on sago production, supplemented by fishing, hunting, and gardening. Gardens produced bananas, coconuts, taro, sweet potatoes, and yams. Pigs, cassowaries, marsupials, and birds were hunted, and small numbers of pigs were domesticated. Betel nuts and tobacco were key trade commodities that once gave the Biwat prominence in the regional trade system. Today, they remain important alongside cash crops such as coffee, rubber, copra, and rice; cattle, pigs, and chickens are also raised.

There were no craft specialists; most adults made what they needed. The Biwat traded tobacco, betel nuts, and garden produce for pottery and baskets from inland groups. Lacking local stone, they exchanged shell valuables obtained from downstream groups for stone tools and mountain products from upriver peoples.

Division of labor was primarily by gender: men conducted rituals, cleared land, hunted, built houses and canoes, and waged warfare; women managed subsistence work, gardening, fishing, cooking, and child care. Both sexes participated in sago processing, with men felling trees and women scraping the pith.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025