Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

SEPIK RIVER

The Sepik River lazily winds through the swampy rainforests of northwestern Papua New Guinea. A placid, almost lake-like river, famous for its colorful tribes, spirit houses, wood carvings and rain forests, it runs for more than 1,100 kilometers (680 miles) and drains an area exceeding 80,000 square kilometers (31,000 square miles). Its winding channel measures between 250 and 500 meters (820–1,640 feet) wide and averages 8 to14 meters (26–46 feet) deep. Along most of its course, a 5–10 kilometer (3–6 mile) belt of active meanders has shaped a vast floodplain up to 70 kilometers (43 miles) wide, containing extensive backwater swamps and around 1,500 oxbow and other lakes — the largest being the Chambri Lakes. The river carries an estimated 115 million tonnes of sediment annually. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Sepik is the longest river on the island of New Guinea and ranks as the third largest in Oceania by discharge volume, after the Fly and Mamberamo rivers. Most of its length lies within Papua New Guinea’s Sandaun (formerly West Sepik) and East Sepik provinces, with a smaller portion running through Indonesia’s Papua province. The river’s large catchment encompasses swamplands, tropical rainforests, and mountain regions. It has often been described as one of the largest relatively unspoiled freshwater wetland systems in the Asia–Pacific region.

The Sepik basin remains largely undeveloped, with no major towns, mines, or large-scale logging operations. The April Salome Forest Management Area lies within the basin. The region has a tropical rainforest climate, with an average annual rainfall of about 339 centimeters (133 inches). The meandering Sepik River is a lifeline for the diverse tribes, serving as the central artery for the region and providing water, food, and transportation. Along its banks dense tropical forests provide a habitat for diverse flora and fauna, including various fish and plant species have been introduced since the mid-20th century.

The Sepik rises in the Victor Emanuel Range of Papua New Guinea’s central highlands near Telefomin. From its headwaters it flows northwest, exits the mountains near Yapsei, and briefly enters Indonesian Papua before curving northeast through the broad Central Depression. It receives numerous tributaries from the Bewani and Torricelli Mountains to the north and the Central Range to the south, including the Yuat River, which is formed by the Lai and Jimmi rivers. Throughout most of its course, the Sepik snakes through the landscape in sweeping bends reminiscent of the Amazon before emptying directly into the Bismarck Sea about 100 kilometers (62 miles) east of Wewak. Unlike many major rivers, it forms no delta and remains navigable for much of its length.

RELATED ARTICLES:

KWOMA (A SEPIK RIVER TRIBE): HISTORY, LIFE, ART ioa. factsanddetails.com

EAST (LOWER) SEPIK PEOPLE — BOIKEN, MURIK, SAWIYANO — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE LOWER (EAST) SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ABELAM AND ARAPESH OF THE SEPIK RIVER: LIVES, HISTORY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE: MASKS, FIGURES AND SHELL RINGS ioa. factsanddetails.com

BIWAT (MUNDUGUMOR): LIFE, RELIGION, FAMILY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

IATMUL PEOPLE OF THE SEPIK RIVER: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHAMBRI: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CROCODILE MEN AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

WEST SEPIK HIGHLANDS PEOPLE — WAPI, TELEFOL, MIAN, GNAU, BIMIN — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

Sepik River Groups

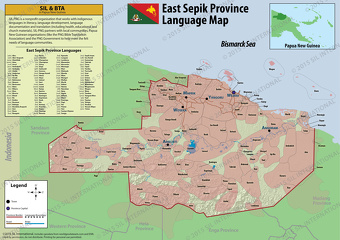

The Sepik River area is one of the world’s most culturally and linguistically diverse regions. More than 300 of the 839 recognized languages in Papua New Guinea are spoken here, with 200 separate tribes, speaking 800 dialects, each corresponding to one or more culture regions of related villages that exhibit similar social characteristics . The tribes along the Sepik River have maintained a variety of distinct traditions, languages, and social structures, although some share some common characteristics. Despite the changing world around them, the Sepik people remain committed to preserving their traditional lifestyle. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

The Ramu River, east of the Sepik River, is another major river in northern Papua New Guinea. Among the groups found in The Sepik-Ramu basin is home to the Torricelli, Sepik, Lower Sepik-Ramu, Kwomtari, Leonhard Schultze, Upper Yuat, Yuat, Left May, and Amto-Musan language families, while local language isolates are Busa, Taiap, and Yadë. Torricelli, Sepik, and Lower Sepik-Ramu are by far the three most internally diverse language families of the region. The largest language and culture group along the river is the Iatmul people. The Iatmul, Abelam, and Sawos are known for their rich artistic traditions, unique spirit houses, and elaborate rituals. The Arapesh and Biwat are relatively large groups. Many of these groups have historically been isolated, contributing to their distinct cultural practices, which include intricate wood carving, mask making, and ceremonial dances. [Source: Google AI]

The Iatmul are a large group that resides along the middle Sepik. The Abelam occupy a large a territory that stretches from the Sepik plains to the foothills of the Prince Alexander Mountains. They are known for yam cultivation and distinct dialects that vary by village. The Sawos inhabits the central coast area around the mouth of the Sepik River. The Arapesh are one of the smaller, more isolated groups whose artistic traditions are part of the broader "Sepik River style". The Boiken are particularly known for mask making. The Biwat, also known as the Mundugumor, resides along the Sepik River and has a rich tradition of art and cultural practices. The Gogodala are populous tribe with a territory that extends from the Aramia River to the lower Fly River, though not exclusively along the Sepik.

The region where many of Sepik tribes live has a warm, humid climate, with rain falling almost every day. This allows crops to be planted at any time of year. The territory of some groups consists of steep ridges with dense forest cover, rarely rising above 457 meters (1,500 feet), and adjacent swampy lowlands filled with sago palms. Birds are abundant, but feral pigs are the only large mammals. Around homes, people plant coconut and areca palms, pawpaw, breadfruit, and paper mulberry trees. Gardens are cleared by burning small patches of forest, and yams, taro, and greens are grown as the first crop, followed by bananas and plantains. [Source: Ross Bowden,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Art of Sepik River Groups

Well-known art from the Sepik River includes detailed wooden sculptures, particularly elaborate masks and figures that represent ancestors, spirits, and mythological beings. The art is diverse due to the many different language groups along the river, but common themes include spirituality, ancestor reverence, and ritual. Traditional artifacts are highly valued, though many older pieces are now in foreign collections. The Iatmul people in particular are well-known for their elaborately carved sculptures.

Art objects from the Sepik River are primarily made of carved wood, often painted with traditional colors and designs. The carvings can be naturalistic or abstract. Common recurring motifs include stylized hooklike forms and triangular shapes. Many pieces have a strong spiritual or ritualistic purpose, such as masks used in ceremonies or to represent spirits.

Sepik tribes demonstrate heir skill in crafting shields, masks, canoes with crocodile head prows, suspension hooks, spirit house posts, ceremonial hooks, orators’ stools, and garamut drums. Each carving tells a story, reflecting the tribe’s connection to their environment, myths, and spiritual beliefs. Among the common types of art are 1) Masks, used in rituals to embody spirits, ancestors, or mythical creatures, and can be ceremonial, oracle, or yam masks; 2) Sculptures, which often depict ancestral figures, mythical beings, or animals; 3) Ceremonial objects, including things like shields, drums, and canoe prows that are used in important community events; and 4) Pole top figures, a highly prized and collectible pieces. 5) Sepik river boats are carved with crocodile heads and other adornments..

Many Sepik river sculptures feature birds that represent the spirit flying away from the deceased person's body. Plastered skulls from Sepik River are similar to ancient skulls found in 10,000 year-old Jericho. Both consist of an actual skull with plaster for skin and sea shells for eyes. Each head is different from the other and some archeologists claim they were sealed "spirit" traps," designed to keep the soul from wandering around. The main difference between the Sepik and Jerich ones is that the Sepik river heads have swirling tribal patterns painted on the face, a pronounced nose and dreadlock-like hair. [Source: "History of Art" by H.W. Janson, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.]

Many art works are found in tambaran (ceremonial houses) (See Below). The arrival of Christianity led some traditional religious art to be neglected or destroyed. Missionaries sometimes became collectors, contributing to the removal of artifacts from the region. Today, artists continue to create traditional pieces, but also make art for tourists and new markets. Papua New Guinea has put controls in place to prevent the export of rare artifacts.

See Separate Article:

ART FROM THE LOWER SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE: MASKS, FIGURES AND SHELL RINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Haus Tambaran — Sepik River Spirit Houses

The villages in the Sepik River region are known for their awesome and colorful haus tambarans. These spirit houses vary from village to village. They are a place where men hang out, smoke and make music. Only men are allowed in, it is taboo in fact for a woman to enter one or sometimes even go near a path that leads to one. Men feel if a woman were to enter all hell would break loose with spirits which are believed to live in the jungles and mountains. Every chicken, pig or human death within a 169 kilometers (100 mile radius) of the village would be blamed on her trespass.

“Haus Tambaran” is Tok Pisin phrase that translates into “Spirit House”. They are specific the Eastern Sepik region. They are large A-framed buildings — sometimes three of four stories high, but generally around two stories — that are made from woven-mating and have grass thatched roofs. They have no windows and the sides of the roofs touch the ground. The triangular part of the structure which faces the central square in the village is wondrously decorated with paintings of the spirits which the villagers believe inhabit the forest. According to Lonely Planet the best houses are in Mapril.

Spirit Houses feature thatched, high-gabled roofs supported by intricately carved wooden support beams. They serve as communal spaces for discussing village matters and conducting rituals. The Iatmul people are particularly known are renowned for their superb artistic ability in painting and carving. Their talents are often exhibited in the construction of these structures. The open sides of the haus revealed interiors filled with intricately carved totems and stools, slit drums (garamut) and masks.

When a dilapidated haus tambaran must finally be replaced its elaborately carved main support pole is usually left standing. Beneath these poles, in the old days, skulls from head hunting expeditions were buried. Today often times the poles are sold by the younger generation, who are more enthralled by the modern world than the spiritual traditions, for an outboard motor or something else. The authentic haus tambaran support poles as well as other Sepik river carvings can fetch thousands of dollars. The more sacred they are the more valuable they are. For many Sepik river villagers selling their culture like this is only way they can make descent money.

Purpose and Symbolism of Sepik River Spirit Houses

Each clan maintains its own Spirit House, located at the physical center and highest point of the village. The Spirit House serves as the focal point of the clan’s social and ceremonial life, particularly for its adult men. It is where men gather daily to talk, chew betel nut, or rest after work. The house also functions as a public forum where men discuss village and clan affairs, and, in former times, planned for warfare. In addition, it is the site for male rituals and initiation ceremonies—rites believed to be essential to the community’s economic, political, and ancestral well-being. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Spirit carvings adorn both the exterior and interior of these houses. Although the Spirit House is an exclusively male domain, its design and artistic symbolism intentionally blend male and female elements to express the idea that “men make men.” The central ridgepole, for instance, is phallic and associated with spears and warfare, while the overall structure is conceived as a female body—its interior likened to a womb. Even the entrance is shaped symbolically as a vagina; to enter the upper story, one climbs a staircase and passes through hanging grass fibers that represent pubic hair.

Latonia Gray wrote in Soul-O-Travels: I was perplexed by the fact the Haus Tambaran entrance is symbolic of the female sex organ and there were representations of reproduction and the womb throughout the structure. This didn’t make sense to me that this would be the very place where males would undergo a ritual to REMOVE all vestiges of female influence upon their lives. Adding to my confusion was the fact that this symbolism was juxtaposed against the carved columns featuring giant phalluses representing male virility. This space became a place where masculinity was based paradoxically upon the mimicry and appropriation of the female anatomy and role as life-giver. I never was able to resolve these contradictions in my mind. I had to accept it for what it was and move on and continue learning about the Sepik culture.

Inside Sepik River Spirit Houses

Male tourists often get invited inside the haus tambarans. Village men sit around inside the dark, smokey building smoking roll-up cigarettes and chewing betel-nut, spitting the lurid betel juice out of trap doors. Eery looking carved masks hang from the ceiling beams and are draped along the walls. Skulls from headhunting expeditions used to be displayed inside these houses as well. According to Soul-O-Travels: The treasures housed here are considered culturally sacred with many representing ancestral spirits. Ngwalndu are huge flat painted faces that represent ancestral spirits. It is believed that the spirits of the ancestors can be summoned and used for consultation.

Slit Drums: Carved from a single felled tree, the slit drum—known locally as the garamut—is the most important musical instrument in the Sepik River region. It is intricately carved and painted in stages and used during ceremonies held in the Haus Tambaran (Spirit House). The people of the Sepik interpret the drum’s sound as its “voice,” capable of carrying over long distances to announce gatherings, summon individuals, issue warnings, or communicate with neighboring villages. These messages are conveyed through complex rhythmic patterns and tonal variations produced with a wooden beater. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The drum rests on two wooden supports so that its body does not touch the ground. Rather than being struck, it is stamped on its surface to create resonant vibrations. Keeping the drum’s belly suspended allows its lower parts to vibrate freely, producing a rich tone that varies depending on where it is stamped. Playing the slit drum requires considerable strength, and during all-night ceremonies, players take turns every 20 minutes. The garamut is central to male initiation rituals and other major ceremonial events.

Sacred Flutes: According to Kaningara mythology, men were once the “life givers,” capable of bearing children, while women held control over the Spirit Houses. Women also possessed a set of magical flutes through which they communicated with the spirits. One night, as the story goes, the men stole these flutes while the women slept, taking with them the power to summon the spirits “that speak to men” during boys’ initiation ceremonies. Since that time, the flutes have been sacred male instruments—strictly forbidden for women to touch or even hear.

Tambuan Costumes: Tambuan costumes are woven from natural materials such as cane, grass, leaves, or the spathe of the sago palm. Masks are fashioned from bark or tapa cloth, mounted on a frame to form a conical helmet. A skirt-like base of raffia fibers completes the full-body costume, often adorned with fresh flowers for ceremonial use. These costumes are worn during sacred dances and special rituals, representing the spirits of birds, animals, or natural forces. When not in use, they are suspended from the gables of the Spirit House, where they remain as both sacred objects and visual reminders of the ancestral world.

See Separate Article:

ART FROM THE LOWER SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE: MASKS, FIGURES AND SHELL RINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Crocodiles — Sepik River Food Sources, Totems and Symbols

Crocodile hunting, an ancient practice handed down through generations, continues to be practiced by the communities along the Sepik River while affirming the crocodile’s deep cultural and totemic importance. The region’s masterful wood carvings — ranging from spirit house adornments to ritual objects — often feature crocodiles. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

For the Sepik River tribes, the crocodile is far more than a formidable creature; it is a sacred being and a totem that embodies divinity, strength, and manhood. Within their mythology, crocodiles are often depicted as ancestral spirits—beings that once emerged from the river, shed their reptilian forms, and became the first humans.

Rooted in both necessity and spirituality, crocodile hunting carries layers of meaning. It provides food and valuable resources such as eggs and skins, yet it also reinforces the sacred relationship between humans and their totemic ancestors. Through this practice, the Sepik peoples continue to honor the crocodile not only as a source of livelihood but as a living link between the physical and spiritual worlds.

See Separate Article: NEW GUINEA CROCODILES: TWO SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Crocodile Men and Sepik River Initiation Ceremonies

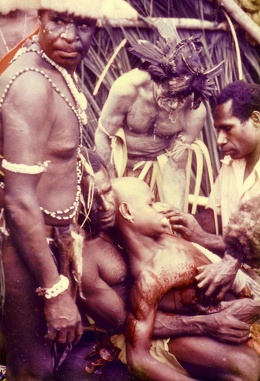

The tribes of the Sepik River engage in a variety of rituals and ceremonies that highlight the significance of tradition in their lives. One such ritual is skin-cutting, practiced by the Chambri and Black Water tribes in East Sepik Province. Occurring every four to five years, this rite involves scarification that mimics the pattern of crocodile skin. It is a transformative experience that marks the transition from boyhood to manhood. The resulting scars, resembling a crocodile's back, become symbols of pride and identity for the men who undergo the ritual. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

Similarly, the Yangit tribe holds male initiation ceremonies, while their female counterparts undergo a unique rite of passage known as Kraku Bandi. During this ceremony, young girls undergo skin cutting after experiencing their first menstrual period. They are kept in isolation for three to four months, culminating in a grand ceremony before they reunite with their families. These ceremonies underscore the importance of rites of passage in Sepik culture, shaping individuals' identities and strengthening community bonds.

Before their dramatic initiation ceremonies boys spent most of their days with the village women and looked upon the haus tambaran and the mysterious spirit music that emanated from within with great wonder. When the ceremony began, there was much crying and weeping from both the mothers and the 11- or 12-year-old boys, as the bond between them was symbolically broken.

During the first part of the ceremony, a mock battle sometimes took place. The initiates rushed the haus tambaran and were fought off by the initiators. After this, the boys crawled into the haus tambaran, where they underwent a ritual in which their mother’s blood — believed to be inferior — was symbolically cast out and replaced with their own virile blood. In the ceremony, the boys’ backs were cut by village elders, creating scores of incisions from shoulder to waist. Ash, mud, and oil were then applied in white and black stripes. This mixture caused small welts to rise on the boys’ skin, leaving permanent scars that made their backs resemble the textured hide of a crocodile.

The ritual flute was another important element of traditional Sepik River culture. Before initiation, boys believed that the sound of the flutes came from forest spirits. The flutes were played during initiation ceremonies and other significant rituals — for example, to help heal a sick girl. Made from bamboo and decorated with animal carvings, the flutes were played through openings on the side, with the player’s fingers positioned between the flute and his mouth. During rituals, men inside the haus tambaran dressed in elaborate costumes to perform the music. These costumes were spectacular—some resembled Hawaiian-style skirts that extended from the shoulders, topped with a mound of fruit and a mask shaped like a housefly’s head. Photographer Malcolm Kirk recorded the sound of the flutes and described it as “a haunting noise that curdled the blood.” The flutes could later be bought by male tourists, but they were wrapped in taro leaves so that women could not see them.

Crocodile Men Tribes

Chambri Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are known for their elaborate skin-cutting ceremonies, unique art, and cultural practices. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea ]

Iatmul Tribe in the Middle Sepik. They are renowned for their distinctive art, including intricate wood carvings and masks, and the construction of spirit houses.

Abelam Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are known for their vibrant yam cult, traditional dances, and distinctive bark paintings.

Kwoma Tribe in the Middle Sepik. They are Celebrated for their distinctive art, especially their intricately decorated ceremonial houses and masks.

Yangoru Boiken Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are known for their distinctive art and carvings, including ancestral figures and masks.

Baiyer River Tribes in the Western Highlands, contributing to the Sepik River region. They are Diverse tribes with unique cultural practices, including engaging with the Sepik River.

Korogo Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are Recognized for their contributions to Sepik art, including wood carvings and traditional masks.

Kaunga Tribe in the Middle Sepik. They are known for their traditional dances and art, with a focus on woodcarvings and storytelling.

Kombio Tribe in the West Sepik Province. They are known for their traditional lifestyles, engaging in subsistence activities and preserving cultural practices.

Kwalea Tribe in the Sepik Plains. They are known for their unique cultural traditions and practices, contributing to the diversity of the region.

Kwanga Tribe in the Sepik Plains. They are Engaged in traditional activities, contributing to the cultural diversity of the Sepik River.

Biwat Tribe in the Middle Sepik. They are known for their artistic expressions, including intricately carved objects and traditional ceremonies.

Wosera Gawi Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are Engaged in traditional agriculture and maintaining unique cultural traditions.

Ambunti Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are known for their cultural practices, including traditional dances and art.

Angoram Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are Engaged in riverine activities, contributing to the cultural diversity of the Sepik River.

Murik Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are known for their participation in the Crocodile Festival and cultural practices centered around crocodiles.

Kanganaman Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are Engaged in traditional practices and contributing to the cultural richness of the region.

Iwam Tribe in the Sepik Plains. They are known for their traditional lifestyles and unique cultural traditions.

Ninggerum Tribe in the Sepik Plains. They are Engaged in traditional practices, contributing to the cultural diversity of the Sepik River.

Arafundi Tribe in the East Sepik Province. They are known for their unique cultural practices, art, and contributions to the Sepik River region.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025