CONVICTS IN AUSTRALIA

In 1788 Britain established New South Wales — and then Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) in 1825 — as penal colonies. Britain and Ireland sent around 162,000 convicts to Australia before ending the practice in 1868. Convicts that served their seven year sentence in Australia were given the choice of returning to Britain or staying in Australia as free people. Those that stayed on received a land grant of 50 acres.

British Parliament designated New South Wales as a convict colony in 1784. The first colony was not established at Botany Bay as is often said. It was established present-day Sydney Harbor. The convicts were sent by British government to Australia under the Transportation Act — viewed as a humane alternative to the death penalty. Australia’s First census in 1828 counted 36,000 convicts and free settlers, as well as 2,549 soldiers.

The status of Australia as a penal colony lasted for about 60 years in the areas of major original settlement. The last shipment of convicts to eastern Australia or Tasmania arrived in 1853, The last in western Australia came in 1868. As late as the 1840s, a third of the population of New South Wales was still officially described as "convict." The penal colony ended in 1840 in New South Wales, with the abolition of transportation of convicts there, and in 1852 in Tasmania). Western Australia, which was founded in 1830 by free immigrants, added convicts to its population by its own choice from 1850 to 1868. Convicts were not sent to South Australia, which became a colony in 1836.

Australia is the only country in the world with a portrait of a convicted felon on its currency. Pictured on the ten dollar bill is Francis Greenway, a convict from England who designed many of Australia's most beautiful buildings. According to Archaeology magazine: “Between 1788 and 1868, men and women were brought halfway around the world, from crowded, draconian Georgian prisons to an uncooperative, alien wilderness more than 30 times the size of Britain. The Crown wasn't merely trying to get rid of these people — well, maybe some of them — it was also trying to start a self-sufficient colony 15,000 miles from home. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2011]

Book: “The Fatal Shore” by Robert Hughes (1986)

Related Articles:

DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA BY EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST EUROPEAN IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, SETTLERS AND SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

ABORIGINAL TASMANIANS: HISTORY, ABUSE, LIFESTYLE AND NEAR EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY FREE SETTLERS IN AUSTRALIA: DEVELOPMENT, SQUATTERS, SHEEP ioa.factsanddetails.com

SETTLERS EXPAND ACROSS AUSTRALIA: CONVICT-FREE STATES, EXPLORERS, GOLD RUSHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS BUSHRANGERS (AUSTRALIAN OUTLAWS): THEIR LIVES, EXPLOITS AND DEATHS ioa.factsanddetails.com

NED KELLY: HIS LIFE, GANG, WRITINGS, ARMOR, DEATH AND MISSING HEAD ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Joseph Banks and the Creation of a Penal Colony in Australia

Sir Joseph Banks, the famous scientist who accompanied Captain James Cook on the 1770 voyage which reached Australia, is credited with coming up with the idea of establishing a penal colony in Australia. Banks recommended Botany Bay to the British government as the place to set up the colony. Banks was impressed by Australia's potential, especially the natural resources, and used his influence as a leading naturalist to advocate for New South Wales as a suitable location for a settlement. The British government decided on this location largely due to Banks's recommendation. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2005 **]

In 1779, Banks told the House of Commons that Botany Bay was the perfect place to set up a convict camp. It was his idea to colonize Australia with undesirables after the Revolutionary War with America was over. Botany Bay was named after the profusion of new plants found there. Banks supported the colonization of New South Wales throughout his life and provided guidance to the new colony. After the first convicts arrived at Botany Bay it was decided present-day Sydney Harbor was a more suitable place to put a penal colony.

In 1786 the British government decided to adopt Bank’s recommendation. Lord Sydney announced that the king had selected Botany Bay as a place to send convicts under a policy called transportation. Before Australia was set up as a penal colony, many convicts were shipped to the British colonies in America. One of Bank’s arguments was Britain needed to find a new destination for convicts after the American Revolution. Considerations other than the pressing need to reduce the convict population may have influenced Lord Sydney, the home minister, in his action. There was, for example, some expression of interest in supplies for the Royal Navy and in the prospects for trade in the future.

First Convicts Arrive in Australia

On May 13, 1787 a total of 736 convicts were stuffed into the stuffy windowless holds of 11 ships, commanded by Captain Arthur Phillips, that left England and sailed for Botany Bay, carrying sheep, cattle and seed, cutting and living plants of peaches, pomegranates, limes, lemons, mustard, garlic, carrots, clover and dozens of other agricultural plants. In addition to the convicts, the first fleet carried nearly 400 administrative people, sailors and marines (who didn't have an ammunition.) There were only two mutinies and 48 deaths on the eight-month journey.

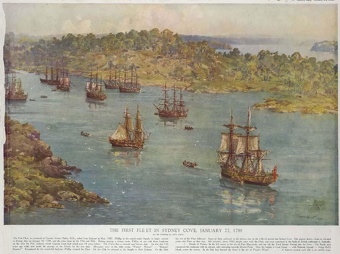

On January 26, 1788, the “First Fleet” landed at Sydney. Captain Phillip of the Royal Navy raised the British flag at Sydney Cove, which he decided was preferable to Botany Bay, slightly to the south, as a settlement site. The colony of New South Wales was formally proclaimed on February 7, 1788. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2005]

Many of the convicts were condemned for offenses that today would often be thought trivial. According to historian Deborah Swiss, the Transportation Act had a very clear economic motive. “The British wanted to beat the French to colonise Australia because it was rich in timber and flax. It was also social engineering in that the British government wanted to remove ‘the unsightly poor’ from their streets. The convict men were transported first and soon outnumbered women nine to one in Australia. You can’t have a colony without women so the female convicts were specifically targeted by the British government as ‘tamers and breeders’.” [Source: Angela Heathcote, Australia Geographic, June 4, 2018]

Penal Colony at Port Jackson (Sydney)

The first settlement — the British penal colony at Port Jackson (Sydney Harbor) — was established in 1788. The first convict settlers from Britain consisted of 548 males and 188 females.

On January 26, 1788, the first boatload of convicts landed in present-day Sydney Harbor. The ships first arrived at Botany Bay. Phillips was disappointed by the landfall and ordered his ships to sail northward until the found what has been described by some as the finest harbor in the world.

January 26 is now celebrated as Australia Day — Australia's national day. Some Australians believe that founding of their country should be celebrated on a different day, for example January 1, when the six colonies formed the confederation of Australia in 1901. Other say Australia was founded 1770 when Cook arrived and other still say the country was really discovered by Aboriginals 55,000 years ago.

At the time the first convicts arrived in Australia ,Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”, it was “as remote, alien and terrifying as the moon today. No other nation in the world has ever been founded on such an experience. These were the first white Australians. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

The first penal colony at Port Jackson was soon enlarged by additional shipments of prisoners, which continued through the mid-1800s. With the increase of free settlers, Australia developed, the interior was penetrated, and six colonies were created: New South Wales in 1786, Van Diemen's Land in 1825 (renamed Tasmania in 1856), Western Australia in 1829, South Australia in 1834, Victoria in 1851, and Queensland in 1859. In the end the convict colony proved to be very expensive for England. Sydney for example was not able to feed itself and food and supplies had to be shipped in.

Crimes of the First Convicts of Australia

At time Australia was established in the late 18th century, the Industrial Revolution was creating great numbers of urban poor who lived in squalid Dickensian ghettos in London and other cities in Britain. Britain's prisons were overcrowded because laws at the time called for imprisonment for debt and petty crimes.

The crimes of the first convicts were things like petty thievery, sheep stealing and pickpocketing. The petty crimes for which many were sentenced were committed to feed themselves and their families. One women was sentenced to seven years for stealing 24 yards of black silk lace. The worst crimes committed by the men were highway robbery and jewel theft.

Many of the first convicts where children who, after being arrested, were given the choice of being hung or sent to Australia. Matthew Everingham, a boy of 14 or 15, was representative of the convicts on the first ship. His crime was pawning two books belonging to an attorney. For this infraction he spent three years in jail in England and then was transported to Australia for a seven year sentence. [Source: "Children of the First Fleet" by John Everingham, National Geographic, February 1988 ~; "Australia at 200" by Ross Terrill, National Geographic, February 1988]

Among the new arrivals on the second fleet were a couple of hundred lady convicts, most of which were described as a "disgrace to the very name of woman." Despite their lack of attributes many of them found husbands and these couples produced the first native born Australians.

About a third of the convicts sent to new South Wales were from Ireland. Many of them had fought against the British. Most of the convicts were given seven year sentences of hard labor and had little hope of ever returning home. The military guards that watched over them were known for their cruelty.

Life of the Early Convicts in Australia

Being shipped off to Australia was the 18th century equivalent of being flown to the dark side of the moon. Unlike lush England, Australia was a barren land of poor soil and dense bush. Crops didn't grow very well and most the of the cattle the ships brought with them escaped. Robert Hughes provides an epic account in his book “The Fatal Shore”.

The first convicts and settlers in Australia nearly died of starvation. Ships that showed up two years later didn't bring supplies as promised. Instead they carried 739 more convicts. There would have been more but 160 people were dumped at sea after succumbing to disease and malnutrition.

Matthew Everingham, wrote: "I turned settler at Ponds on condition of his supporting me for 18 months in provisions and clothing...pretty well inured to hard work and having an agreeable partner...the first six months everything seemed to run against me; my crop failed and daughter died and my wife hung on my hands very ill...the whole colony was almost starving. [Source: "Children of the First Fleet" by John Everingham, National Geographic, February 1988 [~]

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”, The bestiality of their lives in their new home is hard to describe and even harder to contemplate... Despite the hardships of their initial landfall, many of the first Australians won their freedom within a short time and set out to make new lives in a new land. The Commander of the First Fleet in 1788, Captain Arthur Phillip, wanted Australia to be a free settlement and tried hard to release convicts onto the land, striving in many ways to relieve the convicts’ misery. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: Depending on when and where they were sent, convicts experienced a wide range of conditions and treatment — some were rapidly granted parole and given free land, while others were subjected to corporal punishment and solitary confinement. Many of them eventually established families and businesses and became the working class of a successful colony and a modern nation. Others, however, such as the men depicted here, were rogues who bounced in and out of the penal system for most of their adult lives. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2011]

Women Convicts in Australia

The Female convicts sent to Australia were predominantly young, single women who had been domestic servants and/or who had come from a semi-skilled background — such as an apprenticeship. The majority were first time offenders sentenced to transportation for minor theft. Angela Heathcote wrote in Australia Geographic: Transported to a distant land for crimes of poverty, Australia’s female convicts were charged with the task to tame and have children with convict men. After a harrowing six month voyage across the sea to the newly established British colony dubbed New Holland, convict women were either sold off for as little as the price of a bottle of rum or, if sent to Tasmania, then known as Van Diemen’s land, they were marched to the Cascades Female Factory — a damp distillery-cum-prison. Yet, despite their harsh treatment and dark experiences, the story of Australia’s convict women is ultimately one of triumph. [Source: Angela Heathcote, Australia Geographic, June 4, 2018]

Of the the estimated that 164,000 convicts. Who were shipped to Australia between 1788 and 1868 under the British government’s Transportation Act approximately 25,000 were women, mostly charged with petty crimes such as stealing bread. “Half the women landed in mainland Australia and half in Tasmania. Less than 2 per cent were violent felons. For crimes of poverty, they were typically sentenced to six months inside Newgate Prison, a six-month sea journey, seven to 10 years hard labour and exile for life. Clearly, the scope of their punishments far exceeded the scope of their crimes,” Deborah Swiss, the author of The Tin Ticket: The Heroic Journey of Australia’s Convict Women, tells Australian Geographic.

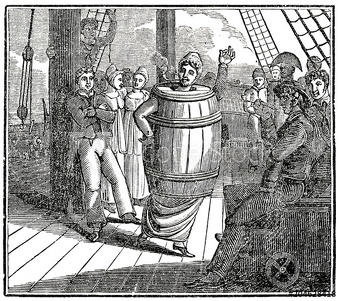

Punishment of disobedient female convict on ship Lady Juliana at a 1789 trip from Britain to Australia

Deborah said: If you were a working-class girl in London or Dublin in the 1800s you had two choices: enter prostitution, which was not a crime or steal food or clothing to be able to live another day. ” According to detailed ship journals, most of the female convicts had never even travelled on a rowboat, let alone a large ship before, so most experienced extreme sea sickness during the voyage. “The women were housed on the orlop deck, the lowest and the smelliest where they slept on wooden bunks that measured eighteen inches wide,” says Deborah.

Records of the lives of convict women living in Tasmania are well-preserved, while those documenting the lives of their counterparts in Sydney have been destroyed. According to the NSW Government many of the records were ordered to be destroyed by the military because they had no use, however some 20th century reports have led Deborah to believe that records may have been destroyed by convict descendants eager to wipe their past clean.

Lives of Women Convicts in Australia

Angela Heathcote wrote in Australia Geographic: Prior to their voyage to Australia, most of the women were incarcerated at Newgate Prison in London, which Deborah says was often referred to as “the prototype of hell”. It was here that the women came into contact with Elizabeth Gurney Fry, the first internationally known female social reformer. Elizabeth gained the nickname the ‘Angel of Prisons’ for her work with female inmates at Newgate, who she regularly visited for over three decades. “Inside Newgate, [Elizabeth] set up a school room where children imprisoned with their mothers could learn to read and write. She also taught the female convicts how to sew so that they would have a skill once freed in Australia,” says Deborah. [Source: Angela Heathcote, Australia Geographic, June 4, 2018]

As they boarded the transport ships, Elizabeth and her volunteers gave each woman a bag that contained scraps of cloth, needles and thread. “Aboard ship the women could make a quilt which could later be sold in Australia for a few coins each.” Only one convict-made quilt has survived the test of time. The Rajah Quilt — named for the ship aboard which the women prisoners and the materials for the quilt arrived in Hobart in 1841 — is now on display at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.

Based on arrest records, court transcripts, description lists, ships journals and newspaper accounts available to her, Deborah was able to create an accurate picture of Tasmanian women’s day-to-day lives. “The newspapers in Van Diemen’s Land reported colorful escapades like the first female flash mob in 1840. They were known to sing and dance naked under a full moon, rebelliously removing their miserably scratchy shifts, which were purposely designed to be uncomfortable,” Deborah says.

And when it came to meeting their future partners, they were very creative. “At the Cascades Female Factory, one of the many rules was that the women were not allowed to speak to men. To find a way to communicate with prospective lovers, the women devised a scheme whereby they smuggled love letters inside chickens that were delivered to a corrupt warden.” Today, the Cascades Female Factory, located in Hobart, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and regularly holds exhibitions on the lives of the convict women housed there.

During her research Deborah came across countless stories that she says exemplify the human spirit. “They were ordinary women who found the courage to become extraordinary because they had no other choice,” she says. Deborah was particularly taken by the story of 12-year-old Agnes McMillan who was transported to Australia for stealing stockings. “Agnes McMillan was left to fend for herself. Her story centers on how human beings find hope where none has the right to exist,” she says. “Her best friend and surrogate big sister Janet Houston was transported and imprisoned with Agnes. Surprisingly, The Tin Ticket also became a story about the power of women’s friendship to see us through the worst of times.”

Then there’s Ludlow Tedder, whose sad story has a bittersweet ending. “As a widow and mother of four children she didn’t make enough to support them. She made the mistake of stealing eleven spoons and a bread basket that she pawned as a means to send her youngest child Arabella to school For her crime, Ludlow received a 10-year sentence. Arabella was transported with her and Ludlow had to leave her other children behind who she would never see again. Once in Van Diemen’s Land, authorities took children away from their mothers and placed them in an orphanage because they wanted the children to be pure of their mother’s sins. By the time she was freed, Ludlow had cleverly saved enough money to essentially buy Arabella back from the orphanage. They left Tasmania for the goldfields in New South Wales and went on to become respected property owners.”

Convict Mothers and Woman’s Prisons in Australia

According to Archaeology magazine: In the first half of the nineteenth century, 12,000 British female convicts were sent to the prison colony in Van Diemen's Land, now known as Tasmania. The island had a reputation for brutality, though the women, who were employed in sewing and textile production, had a variety of ways to subvert the colony's draconian rules, including obtaining alcohol and tobacco while in solitary confinement. One of those rules forbade convicts, held in work camps called "factories," to have contact with their babies except for breastfeeding. But a recent find at the Ross Female Factory shows that they skirted that rule, and may have actively resisted separation from their children. In the prison's Nursery Ward, Eleanor Conlin Casella of the University of Manchester uncovered lead seals (above) that were attached to bolts of cloth, along with fragments of buttons and thimbles. These show that convicts were working with textiles in the nursery, and must have been allowed informal contact with their young children — at least until the children turned three, when they were transferred to a distant orphan school. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2012]

Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney was home to two nineteenth-century institutions for women: the Female Immigration Depot, which housed newly arrived immigrants who stayed for a short time before joining their families or other households as domestic workers, and the Asylum for Infirm and Destitute Women, which housed women unable to support themselves. The official diet served in these institutions was bread, meat, and boiled vegetables, but archaeological investigations have revealed that residents supplemented these monotonous rations with a cornucopia of fruits. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2025

Archaeologists working at the barracks several decades ago discovered more than 3,500 pieces of plant remains trapped beneath the building’s floorboards. Kimberley Connor, an archaeologist at Stanford University, recently studied this collection and found that more than four-fifths of the remains were pits or stems from stone fruits such as cherries, apricots, and plums. Peaches were by far the most popular fruit—1,469 peach pits were recovered. “Peach trees aren’t native, but they grew really well in the environment around Sydney,” Connor says. “There are historical accounts of people feeding pigs fresh peaches by the wheelbarrow full.”

It’s unclear whether authorities condoned the women’s snacking. Connor notes that many of the discarded items were so large that residents would have had to lift the floorboards in order to hide the evidence of their fruit consumption. Women were allowed to periodically leave the barracks to attend church or visit friends, and these forays would have offered opportunities to purchase or harvest fruit. In addition to stone fruits, residents also favored oranges, dates, and bananas. Among the rarer fruits in the collection are a few scraps of lychee skin and a set of 19 seeds from what appears to have been a single cherimoya, a fruit native to South America, the first find of its sort in Australia’s archaeological record. “The sheer range of fruits women in these institutions were eating is really remarkable,” says Connor.

Australian Convict Sites — UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Australian Convict Sites are a collection of sites inscribed as a single UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2010, According to UNESCO: The property includes a selection of eleven penal sites, among the thousands established by the British Empire on Australian soil in the 18th and 19th centuries. The sites are spread across Australia, from Fremantle in Western Australia to Kingston and Arthur's Vale on Norfolk Island in the east; and from areas around Sydney in New South Wales in the north, to sites located in Tasmania in the south. Each of the sites had a specific purpose, in terms both of punitive imprisonment and of rehabilitation through forced labour to help build the colony. [Source: UNESCO]

The sites illustrate the different types of convict settlement organized to serve the colonial development project by means of buildings, ports, infrastructure, the extraction of resources, etc. They illustrate the living conditions of the convicts, who were condemned to transportation far from their homes, deprived of freedom, and subjected to forced labour.

This transportation and associated forced labour was implemented on a large scale, both for criminals and for people convicted for relatively minor offences, as well as for expressing certain opinions or being political opponents. The penalty of transportation to Australia also applied to women and children from the age of nine. The convict stations are testimony to a legal form of punishment that dominated in the 18th and 19th centuries in the large European colonial states, at the same time as and after the abolition of slavery.

The property shows the various forms that the convict settlements took, closely reflecting the discussions and beliefs about the punishment of crime in 18th and 19th century Europe, both in terms of its exemplarity and the harshness of the punishment used as a deterrent, and of the aim of social rehabilitation through labour and discipline. They influenced the emergence of a penal model in Europe and America. Within the colonial system established in Australia, the convict settlements simultaneously led to the Aboriginal population being forced back into the less fertile hinterland, and to the creation of a significant source of population of European origin.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Australian Convict Sites by UNESCO whc.unesco.org

Archaeological Remains and Photographs from Australia's Convict Era

In Sydney's oldest neighborhood, The Rocks, archaeological remains from the convict era — when Australia was a British penal colony — have been preserved in situ beneath a modern hostel.Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: The posh new youth hostel in The Rocks, is built on stilts. Below and around this backpackers' haven is a tableau of everyday life from modern Australia's first years, when it was a penal colony and the most remote branch of the British Empire. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2011]

The foundations and other artifacts here were revealed during extensive archaeological digs in 1994 that uncovered almost two full blocks between Cumberland and Gloucester streets. Wayne Johnson, an archaeologist with the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority, beams with pride about the hostel, which was designed to preserve in situ the remains of 48 houses and shops occupied by convicts and ex-convicts. The city really seems to embrace its criminal heritage, though in some parts of the country, the convict "stain" is still a sore point.

Very few photos exist from the convict period, but the Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority in Tasmania maintains a collection convict portraits, most from later in the convict era, when photography was available. These short bios were assembled by Julia Clark and the portraits supplied by Susan Hood, both of the Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority.

Legacy of Australia's Convict Era

About 22 per cent of Australians today are descended from convicts and the convict days are not all that long ago for some Australians. Survivors of the last convict ships, which arrived 1868, lived until the 1920s .The dual heritage of convicts and free settlers and what this means is still alive today. In his book, The Fatal Shore, Robert Hughes argues that the "convict strain" — described as the social ostracising that came with having convict heritage — is present for much of confusion by Australians about their identity and purpose.

As of 1988 Matthew Everingham, described earlier had left behind 6,500 descendants. Among them was the inventor of the world's first fool-proof instant souffle; a fire and brimstone preacher who smuggled a million Bibles from Hong Kong to mainland China; and a station manager who fallen off a windmill, rolled three cars and survived various barroom brawls. At the last count he had 32 mended broken bones. [Source: "Children of the First Fleet" by John Everingham, National Geographic, February 1988]

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”, Ever since 1788, Australians have consciously or subconsciously been concerned to remove from their lives what Robert Hughes has called ‘The Stain’ of their convict past, studiously donning a camouflage of almost stultifying respectability for a while. Even in the 19th century, it was ill-mannered to use the term ‘convict’ in Australia; the euphemism ‘government man’ was preferred. This has changed in recent years to a sort of inverse snobbery where it is considered a proud pedigree to be able to trace one’s genealogy to a convict ancestor. It is in this convict context, however, that one can begin to understand why any imposition of authority, any infringement of personal liberty, no matter how seemingly petty, will arouse Australian passions to fever pitch. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

Many of the convict women’s descendants that Deborah interviewed for her book suffered from the ‘convict stain’. However, Deborah told Australian Geographic says that revisionist history is starting to set the story straight. “I was intrigued by the convict maids because women have been largely ignored in history as have the lives of the working class. I view the female convicts as heroic because they triumphed over tragedy as their lives transformed from desperation and injustice to freedom alongside a new start in a new land.The miracle of their story is that the vast majority of these women went on to become loving mothers and grandmothers. [Source: Angela Heathcote, Australia Geographic, June 4, 2018]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, National Library of Australia

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025