Home | Category: History / Government, Military, Crime

NED KELLY

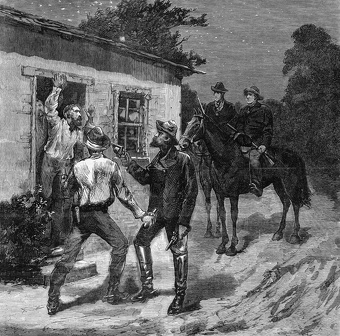

Ned Kelly in armor, Wood engraving published in The Illustrated Australian News, 1880 State Library of Victoria

Ned Kelly towers above the competition as Australia's most famous and popular folk hero. Described as an "Homeric epic hero," "The joking saint," "Australia's Petrushka" and "the prototype of the Australian's own idea of himself," he was a "bushranger" (an Australia equivalent of a Wild West outlaw) who killed three policemen, robbed two banks and battled police in suit of homemade armor. He was hanged in 1880 at the age of 26. [Source: Gavin Souter, Smithsonian]

To some Kelly was a folk hero and a symbol of resistance against British colonialism. To others he was simply a thug and a murderer. His story lives on in more than 150 books as well as films, television shows, a ballet and musicals. Mick Jagger, with a horrid Irish accent, played him in a 1970 film. A year later Johnny Cash recorded the song “Ned Kelly” for his album “The Man in Black.” More than a dozen other films about Kelly were made. “Ned Kelly” (2003) starred Heath Ledger as Ned and also featured Orlando Bloom, Naomi Watts and Geoffrey Rush. "I think a lot of Australians connect with Ned Kelly and they're proud of the heritage that has developed as a result of our connection with Ned Kelly and the story of Ned Kelly," Melbourne school teacher Leigh Olver, who is the great-grandson of Kelly's sister Ellen, told Reuters. [Source: Reuters, September 1, 2011; Rhys Blakely, The Times of London, September 2011]

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Kelly is one of the most iconic and polarizing figures in Australian history. He is the most famed of the guerilla bandits known as bushrangers, some of whom, in their day, personified revolt against the colony's convict system and against the excesses of wealth and authority. There's no real non-Australian analogue for Kelly — he was part Clyde Barrow, part Jesse James, part Robin Hood, but with media savvy and a strong political sense. To some, particularly Australians of Irish descent, he's a populist hero. To many others, he's a cop-killer, and his lionization is distasteful at best. He is, at the very least, an enduring subject of fascination. [Source:Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

Book: “True History of the Kelly Gang” (a novel) by Peter Carey (2001); “Ned Kelly: A Short Life” by Ian Jones (1995), an excellent biography

Related Articles:

FAMOUS BUSHRANGERS (AUSTRALIAN OUTLAWS): THEIR LIVES, EXPLOITS AND DEATHS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY CONVICTS IN AUSTRALIA: MEN. WOMEN, CHILDREN, THEIR LIVES AND LEGACY ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY FREE SETTLERS IN AUSTRALIA: DEVELOPMENT, SQUATTERS, SHEEP ioa.factsanddetails.com

SETTLERS EXPAND ACROSS AUSTRALIA: CONVICT-FREE STATES, EXPLORERS, GOLD RUSHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Ned Kelly and Australian Culture

Ned Kelly has been the source of some of Australia's most beloved folk stories, hundreds of bad songs and the really bad movie made in 1970 with Mick Jagger. The title of the popular Australian novel, “Such Is Life”, written by Joseph Furphy and published in 1903, was taken from Ned Kelly's last words before he was hung.

Kelly made his big screen debut in 1906 in six-minute silent feature “The Story of the Kelly Gang. The costumes included a suit worn by a real-life member of the gang. It depicted Kelly as “the last of the bushrangers,” a distnction which got the film banned in parts of Australia for glorifying criminality. Kelly's use of homemade armor to protect himself from police bullets was even given a nod during the 2000 Sydney Olympics, when actors on stilts dressed in similar armor were featured in the opening ceremony.

One of Australia's most beloved painters, Sir Sidney Nolan, made a name for himself painting paintings linked to the Kelly legend. Nolan once said, "The history of Ned Kelly possesses many advantages...Most of us had heard of it, in one way or another, during our childhood...It is a story arising out of the bush and ending in the bush."

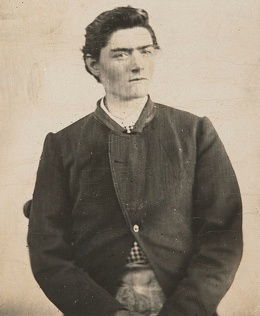

Ned Kelly's Early Life and Appearance

Kelly was born in 1855 in the town of Beveridge, 25 miles north of Melbourne. Baptized Edward Kelly, he was the son of John "Red" Kelly, an Irish Catholic from Tipperary sent to Australia with a sentence of seven years for stealing two pigs, and Ellen Kelly, the daughter of Irish free settlers. When Kelly was 11 his father died. In the 1860s, when Kelly was in his teens, his family moved into the mountainous sheep-and-cattle region of northeastern Victoria. Kelly turned to crime around that time.

Kelly was also widely regarded as a first rate horseman and a crack shot with a rifle and pistol. One policeman described him as "about six feet, dark complexioned, dark moustache, almond-shaped eyes, dark brown whiskers and hair. A raw bony man." Kelly had a love affair with Mary Hearn, who bore him a daughter

Kelly became the bareknuckle "champ" of northern Victoria at the age of 19 after he won a 20-round fight with a man called Wild Wright. Kelly later boasted, "While I had a pair of arms and a bunch of fives at the end of them they never failed to peg out anything they came in contact with."

Ned Kelly's Early Life of Crime

Ned Kelly’s early crimes included assault and cattle theft. His most ruthless crimes, such as killings, police gunfights and bank raids, began after he and his brothers were fugitives. When Kelly was 14 he was acquitted on charges of assaulting and robbing a Chinese pig-and-fowl merchant named Ah Fook, who testified that Kelly had told "I'm a bushranger." At the time Kelly may not have been a bushranger himself but he was associating with the gang of real bushrangers led by a man named Harry Power.

When Kelly was 16 he was charged with Power for armed robbery. Power was sentenced to prison but Kelly was acquitted. A few months after however Kelly was sentenced to three months in jail for assault and three months of indecent behavior. Apparently he struck someone who called him a horse thief and sent the accuser's wife a calf testicle and note that maybe her husband needed it.

In 1871, Kelly was sentenced to three year's in prison for receiving a stolen horse. After his release he worked as a sawmill worker, lumberjack, sheep shearer, stockman and a fencer. In his lifetime, Kelly and the 13 members of his family his family were arrested 71 times and given 26 prison terms. His home was considered a den of thieves. His mother was once charged with "furious riding" in a public place.

Ned Kelly, the Writer

Kelly left behind two documents written in his own hand: a 3,800-word apologia known as the Cameron Letter written to a member of the Victoria Parliament while he in the town of Eurora, and the 7,400-word statement known as the Jerilderie Letter in which he both thumbs his nose at authorities and defends his actions.

Although Kelly had trouble with grammar and punctuation marks he sometimes expressed himself quite eloquently. He wrote: “This history is for you and will contain no single lie may I burn in hell if I speak false... I'm sure you know I have spilled human blood when there were no other choice at that time I were no more guilty than a soldier in a war...It will pay the government to give those people who are suffering innocence justice and liberty if not I will be compelled to show some colonial stratagem which will open the eyes of not only the Victorian Police and inhabitants but also the whole British army.'

Describing his contempt for anyone of Irish ancestry who would think of joining the police he wrote it was cowardly and selfish "to serve under a flag and nation that has destroyed and massacred and murdered their forefathers by the greatest torture as rolling them down hill in spiked barrels pulling their toe and finger nails and on the wheel and every torture imaginable."

Kelly also wrote that those not tortured were sent to Australia "to pine their young lives away in starvation and misery among tyrants worse than the promised hell itself all of true blood, bone and beauty that was not murdered on their own soil, or had fled to America or other countries to bloom again another day were doomed to...Norfolk island and Emu plains and in those places of tyranny and condemnation many a blooming Irishman rather than subdue to the Saxon yoke were flogged to death and bravely died in servile chains but true to the shamrock and a credit to Paddys Island."

Kelly once called he Victorian police as a "parcel of big ugly, fat-necked wombat headed, big bellied, magpie legged, narrow, hipped splaw-footed sons of Irish bailiffs or English and lords." He once bragged he would peg police informers "in an ant-bed with their bellies opened their fat taken out rendered and poured down their throat boiling hot."

Ned Kelly's Life of Crime Picks Up

In 1877, four policemen tried to arrest Lelly for drunken behavior. An attempt to handcuff him produced a nasty brawl. Kelly later wrote: "When they could not" handcuff me a policemen and constable "Fitzpatrick tried to choke me, and Lonigan caught me by the privates and would have killed me but was not able. Mr McInnes came up and I allowed him to put the hand-cuffs on when the police were bested." Kelly vowed, "If ever I shoot a man, Lonigan, you will be the first."

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: Young Kelly ran afoul of the law throughout his teens, but his bushranging career didn't really begin until April 1878, when a constable arrived at the family home to arrest Ned's brother Dan, and afterward claimed that the Kelly family had attacked him. The brothers, who denied the accusation, took to the bush. Their mother, Ellen, was charged with attempted murder for the incident and sentenced to three years, fueling Ned's hatred of the police and distrust of government. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

According to one account, Fitzpatrick showed up at the Kelly family compound without a warrant and attempted to arrest Kelly’s brother Dan. According to another account he went there to ask Kelly’s sister’s Kate out for a date. In any case, Kelly's mother reportedly hit Fitzpatrick over the head with a shovel and three shots were fired at him, one of which wounded Fitzpatrick in the hand. Who fired the shots is mystery. Historians believe it was either Ned or Dan although Ned claims he was in New South Wakes at the time.

After the incident warrants were issued for Ned and Dan on the charges of attempted murder. Ellen was arrested for aiding and abetting their attempted murder. Afterwards, Ned and Dan teamed up with their friends, Joe Byrne and Steve Hart. Together, they formed the Kelly Gang, which spent the next 21 months ramping up their exploits.

Kelly Gang Kills Three Policemen at Stringybark Creek

In October 1878, four mounted policemen rode off in pursuit of the Kelly gang in the Wombat ranges. They camped at Stringybark Creek and were discovered by Kelly's gang before they discovered them. Because they were outgunned, according to one source, the gang ambushed the policemen and three policemen were killed by Kelly, including the aforementioned Lonigan. The fourth man was disarmed and allowed to return, presumably to tell the story of what happened.

Kelly wrote in the Cameron Letter: "I could not help shooting them or else lie down and let them shoot me." In the Jerilderoe Letter he wrote: "Those men came into the bush with the intention of scattering pieces of me and my brother all over the bush and yet they know and acknowledge I have been wronged. And is my Mother and infant baby and my poor little brothers and sisters not to be pitied more so, who has got no alternative only to put up with brutal and unmanly conduct of the police who have never had any relations or a Mother or must have forgot them

After the Stringybark Creek incident, the “reward for the gang's capture went from £100 to £500 per man, dead or alive. In December, they took 22 hostages at a sheep station and then robbed the National Bank in Euroa of £2,000. The reward doubled. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

Ned's violence is often seen as the inevitable and tragic result of police persecution of poor Irish settlers. Jane Rogers wrote in The Observer: The motivation for the first murder Ned actually commits, at Stringybark Creek, is devastating. His mother has pointed a gun at a dishonest policeman, Fitzpatrick, who has betrayed Ned's sister. Despite being rescued by Ned, Fitzpatrick later accuses him, his mother and his brother of attempted murder. The mother is imprisoned for three years and the brothers go into hiding, where word is brought to them of police preparations to pursue them. [Source: Jane Rogers, The Observer, January 7, 2001]

The preparations include the manufacture of 'undertakers', long leather straps for buckling a corpse on to a horse. imaginng what Kelly might have thought Peter Carey wrote: 'We imagined our undertakers the leather straps lay fully revealed like giant tapeworms nestling in our guts all our lifetimes growing larger every day.' The gang decide to confiscate the police weapons, but when they creep up and yell to the police to stick up their hands, one takes cover and raises his gun. 'What choice did I have? I squeezed the fateful trigger. The air were filled with flame and powder stink Strahan fell thrashing around the grass moaning horribly... on the ridges the mountain ash gleamed like saints against the massing clouds but down here the crows and currawongs was gloomy their cries dark with murder.'

Kelly Gangs Robs Two Banks and Throw the Police in Jail

The Kelly gang robbed two banks. The National Bank in Eurora, and two months later they took £2,410 from the Bank of New South Wales in Jerilderie. In Jerilderie, Kelly and his gang locked up the town's entire police force in jail and put on a show of horsemanship, wearing the policemen's uniforms, in front of a cheering crowd. The gang burned the bank's mortgage deeds, claiming (erroneously) they were freeing debtors from the clutches of the bank. Kelly gave children the day off from school and entertained people at the local saloon with stories from his life.

In Jerilderie, in February 1879, the gang took over a police station of locked up the officers there while they robbed the Bank of New South Wales wearing police uniforms, after which they rounded up 60 people at the Royal Hotel next door. There, Ned dictated a fiery, quasi-political, 8,000-word manifesto about his Irish roots and the injustice of the courts and convict system. The reward was doubled again and Aboriginal trackers were brought in to find them. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

Kelly was an example of what the English sociologist E.J. Hobsbawm called a social bandit. Hobsbawm once wrote, "the point about social bandits is that they are peasant outlaws with the lord and state regard as criminals, but who remain within peasant society, and are considered by their people as heroes, as champions, avengers, fighters for justice."

Armored Showdown at the Inn in Glenrowan

Kelly’s most audacious and iconic moment came at an Inn in Glenrowan during his final shootout, when he donned makeshift metal armor and attempted to flank the police. In 1880, Kelly devised a plan to shoot a former friend who became a police informer on a 250-kilometers (160-mile) stretch of railway between Melbourne and Mangaratta. The informer was killed according to plan on June 26, 1880. The rails were torn up after the last passenger train had passed through Glenrowen in an attempted to derail a special police train sent to bring them in..

It took the police a few days to arrive. In the meantime the gang took over the Ann Jones Inn in Glenrowan and drank and partied with sympathizers and hostages and fashioned armor suits to wear in the climatic shoot-out. Kelly's armor suit was made out of plow steel and weighed 44 kilograms (97 pounds). It consisted of a cylindrical helmet with an eyeslit, breastplate and skirt.

The gang was finally tracked down at the Ann Jones Inn with the help of a former teacher and hostage. The police approached quietly before dawn and opened fire. Kelly was heard saying, "Fire away you bloody dogs!" The four members of the Kelly gang held off the police who peppered the rustic building with shots for hours.

Kelly was the only member of his gang to survive the shootout. Joe Byrne was shot seconds after pouring himself a brandy at the bar. All the hostages and sympathizers escaped although two children and an old man were shot. Byrne was killed in the shootout and Dan Kelly and Steve Hart took poison before the police set the building on fire.

At around seven in the morning, Kelly emerged from the hotel in his suit of homemade armor. He managed to flank the cops and come out of the shadows in his armor, shooting a pistol. The police tried to kill him by aiming at the slit in the helmet but succeeded only in bruising his face. His legs weren't protected and he was finally brought down with two shots to the legs. Kelly was shot in the foot and arm early in the battle and received 30 wounds even though he wore armor.

Archaeology Excavations in Glenrowen

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Adam Ford, founder of archaeological consulting firm DIG International, led a 2008 excavation of the site where the inn once stood. The plot had seen three different structures: the first Ann Jones Inn, which burned down at the end of the siege; a second hotel built by Jones, which was also lost to fire; and a brick wine shanty (a sort of unlicensed watering hole) that was demolished in the 1970s. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

Ford worried that construction and decades of artifact collection — which began feverishly immediately after the siege — would leave little evidence behind. "I was quite fearful that I'd get there and there wouldn't be any remains left," Ford says. But the site was surprisingly intact: Around and beneath the foundations of the wine shanty were carbonized wall and floor timbers, bits of ceramic and melted glass, and, most importantly, nearly 100 pieces of ammunition.

“Ford and his team approached the site as a battlefield, looking for patterns that might say something about the shootout between the gang and police. The archaeologists found a line of some 40 deformed bullets where there had been a wall separating the inn's front and back rooms. Behind that wall, in just one square yard of space, the team found approximately 30 cartridges and percussion caps, including one that matched a gun said to be Kelly's. The pattern suggests that the gang found little protection in the inn's three front rooms, so they retreated to the back rooms to reload before coming out to resume firing. "We were able to identify the actual movements, and perhaps even the motivations, of the members of the Kelly gang in their final hours," says Ford. "It is a powerful vision of these four young men who, for whatever reason, had got themselves into a situation they were never going to get out of."

Ned Kelly’s Death and the Fate of His Remains

Ned was the only member of the Kelly Gang to survive. After being given time to recover from his wounds, he was tried for the murder of Lonigan and was found guilty and sentenced to death. A few months later, November 11, 1880, he was hanged at the age of 26 at Old Melbourne Gaol. A gaol is a prison. Reportedly, 8,000 fans and sympathizers turned out at a rally for his reprieve. His last words are said to have been, "Ah well, it has come to this." .

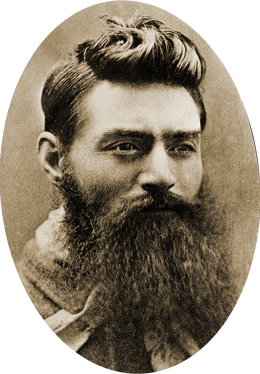

Kelly sat for a portrait the day before his execution in 1880. The photograph shows a man with a popular-style haircut, piercing feminine eyes and a long John-Brown-style black beard. Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: “In the photo, Ned Kelly's eyes are fixed in a firm, defiant gaze. Though much of his face is hidden beneath a thick beard, it is possible that a little smile plays about his lips. But it's hard to tell for sure. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

Kelly's death mask is on display in the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. After his execution at the Old Melbourne Gaol he was buried within the prison grounds in a narrow graveyard in what was known as the old men’s yard alongside 40 or so other prisoners. The initials of the executed men were etched into the wall above each plot. For Edward "Ned" Kelly, "EK" was etched. In May 1881, rumors circulated that his body had been illegally dissected by medical students, sparking public outrage and fears of civil unrest. The governor of the gaol was forced to publicly deny the claim. {Source: Wikipedia[

When the Old Melbourne Gaol closed in 1929 for demolition works, the remains of executed prisoners were unearthed. Workers and onlookers looted skeletal parts from several graves before the remains were reinterred in a mass grave at Pentridge Prison. Among them was a grave marked “E.K.”, located apart from the others. The skull from this grave was handed to police, later stored by the Victorian Penal Department, and in 1934 sent to the Australian Institute of Anatomy in Canberra. It went missing for decades before being found in a safe and later displayed at the Old Melbourne Gaol from 1972—until it was stolen in December 1978.

In 2008, archaeologists announced they had discovered what they believed to be Kelly’s burial site at Pentridge Prison, among the remains of 32 executed felons. The stolen skull was eventually returned in 2009 for forensic testing alongside the newly recovered remains. However, DNA analysis in 2010–11 confirmed that the skull was not Kelly’s. Kelly’s skeleton was identified among the Pentridge remains through DNA testing and by matching bullet wounds consistent with those he received during the Glenrowan siege. The skull remains missing, though the occipital bone of the skeleton shows cut marks consistent with dissection.

In 2012, the Victorian government authorised the return of Kelly’s remains to his descendants, who requested that his skull also be repatriated. On 20 January 2013, following a Requiem Mass at St Patrick’s Catholic Church in Wangaratta, Ned Kelly was reburied in consecrated ground at Greta Cemetery, near his mother’s unmarked grave. His coffin was encased in concrete to deter future grave robbing. Kelly’s original headstone, along with others from the Old Melbourne Gaol, was repurposed during the Great Depression—the bluestone slabs used to build sea walls protecting Melbourne’s beaches from erosion.

For a more detailed look on all this see “Final Resting Place of an Outlaw” by Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012 archaeology.org; “Ned Kelly's skull is still missing, and the mystery continues to grow 138 years after his death” by Anna Priestland, ABC, November 11, 2018 abc.net.au

Analysis of Ned Kelly’s Remains

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The mtDNA from the surviving Kelly ancestor was a match to a set of remains from the third pit” at Old Melbourne Gaol. “Surprisingly, the matching remains were among the most complete of any of the Pentridge burials. They were missing only a few cervical vertebrae, some small bones, and the skull, except for a palm-sized fragment — further proof that the intact Baxter skull could not have been Kelly's. "The Kelly remains are almost complete. It's one of the best sets of remains from the entire site. That I did not expect at all," Jeremy Smith, an archaeologist at Heritage Victoria, told Archaeology magazine. "It contradicted the historical evidence that Kelly's burial had been targeted by trophy collectors." [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2012]

“Closer examination of the bones showed unmistakable evidence of Kelly's injuries from the shootout at the Ann Jones Inn. Injuries to the top of the right tibia, the left arm, and the right foot all matched those documented by prison surgeon Andrew Shields when he examined Kelly after arrest. Using an otoscope and dental instruments, Ranson even removed two lead pellets from the tibia. "We had genetic evidence and a lot of anthropological evidence, and then when we looked at the historical evidence as well, it really tied it all together," says Soren Blau, the forensic anthropologist who examined the remains. Smith describes the outcome as "staggeringly conclusive."

“The skull fragment with the Kelly remains came from the back of his cranium, and shows saw marks across the top and down the sides. The cuts clearly continue on the cervical vertebrae below. A physician had explored the remains of Kelly with more than his eyes. In that era, authorities were concerned with whether hanging was indeed an instantaneous, humane form of execution. Hangings were known to have been botched, resulting in long, drawn-out choking rather than death from a hangman's fracture — a quick, decisive snap of the neck. "This piece of skull suggests the individual had been subject to a limited autopsy, probably to investigate the interior back half of the neck following an execution," says Blau. "That was probably not uncommon given that there was interest in whether hangings were effective or not, and it was important for the jail to say that it was a successful hanging."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025