Home | Category: History / Government, Military, Crime

BUSHRANGERS: AUSTRALIAN OUTLAWS

Bushrangers were armed robbers and outlaws who lived in the Australian bush from the 1780s to the early 20th century. The term originated in the early years of British colonization of Australia and was first used to describe escaped convicts hiding in the bush from the authorities. By the 1820s, the term evolved to refer to people who committed armed robbery as a way of life and used the bush as their base. [Source: Wikipedia]

The tradition of bushranging in Australia began with the arrival of the First Fleet. Convicts who escaped from the Sydney settlement, such as John "Black" Caesar, vanished into the surrounding bush. For more than a century, bushrangers struck fear into and fascinated the Australian population. Bushranging peaked during the gold rushes. Gold escorts and diggers returning from the goldfields were vulnerable to attack. Outlawed bushrangers could be shot on sight. One notorious example is the Kelly Gang and the standoff at Glenrowan in 1880. The popularity of the bushrangers and their ethos of "fighting before surrendering" was commemorated in bush songs and folklore. [Source: State Library, New South Wales]

Two of Australia's most enduring heroes are from come from the Murray River area near Melbourne — Ned Kelly and Jack Riley. Riley is the man that inspired the poem which in turn inspired the movie "The Man from Snowy River." His greatest love was chasing brumbies, or wild horses, in the Australian Alps. He once dove his horse off a cliff, a feat which inspired the poem. Riley has been called a bushranger but he wasn’t. The name "Riley" was also used by a notorious bushranger in the New England area, leading to the confusion.

One of Queensland's most famous outlaws is Henry Redford, a cattle rustler who brazenly stole a thousand head of cattle in 1870 and drove them a thousand miles across uncharted desert to a cattle market in South Australia. He would have gotten away with crime expect a distinctive white bull gave him a way. The public was so taken by Redford that during his trial the jury judged him not guilty on the condition he return the cattle. When an angry judge ordered them to reconsider the jury then ruled that Redford could keep the cattle.

Related Articles:

NED KELLY: HIS LIFE, GANG, WRITINGS, ARMOR, DEATH AND MISSING HEAD ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY CONVICTS IN AUSTRALIA: MEN. WOMEN, CHILDREN, THEIR LIVES AND LEGACY ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY FREE SETTLERS IN AUSTRALIA: DEVELOPMENT, SQUATTERS, SHEEP ioa.factsanddetails.com

SETTLERS EXPAND ACROSS AUSTRALIA: CONVICT-FREE STATES, EXPLORERS, GOLD RUSHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS AT THE TIME EUROPEAN COLONIZATION BEGAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA ABORIGINALS FROM 1900 TO PRESENT: DISCRIMINATION, ASSIMILATION, SOME RESTITUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALIA’S STOLEN GENERATIONS: VICTIMS, LAWS, RATIONALE, OUTRAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

'Brave' Ben Hall

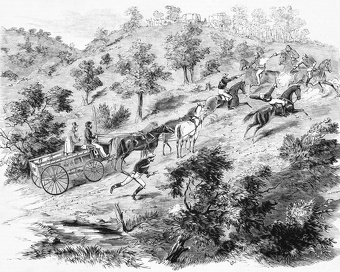

“Bushrangers on the St Kilda Road” by William Strutt's, 1887, depicts "one of the most daring robberies attempted in Victoria" in 1852

'Brave' Ben Hall (1837-1865) was born to ex-convicts in Maitland, New South Wales. One of Australia’s so-called “gentleman bushrangers,” he was a skilled stockman who once leased a run near Wheogo with a partner. Though his life was brief, the dramatic exploits of “Brave Ben Hall” have inspired films, television, music, and poetry. [Source: Australia Mint]

In 1862, Hall was arrested on the orders of Sir Frederick Pottinger, suspected of armed robbery. Soon after, his wife Bridget left him, taking their young son. Hall was detained again on a charge of gold theft, but released without trial. When he returned home, he found his house burned by Pottinger and his livestock gone—either stolen or scattered.

Bitter and dispossessed, Hall joined the Canadian-born bushranger John Gilbert, eventually becoming leader of his own gang. In 1865, Hall and his gang were declared outlaws, and a £1000 reward was placed on Hall’s head. Hall’s gang was well-organized and fast-moving, often using stolen racehorses to outrun the police.

Hall himself was known for his courtesy and reluctance to use violence, a code not always observed by his companions. At times, his raids seemed more about defying authority than personal gain. In one famous incident at Canowindra, the gang held the town for three days, hosting a lively celebration with its residents before departing without taking anything.

Although Hall reportedly planned to abandon bushranging, he was betrayed by an informer and ambushed near Forbes in May 1865, where he was shot and killed by eight policemen. Ben Hall was buried in the Forbes cemetery. His funeral was said to be “rather numerously” attended—especially by women.[Source: Australia Mint]

Kenniff Brothers — Queensland’s Last Bushrangers

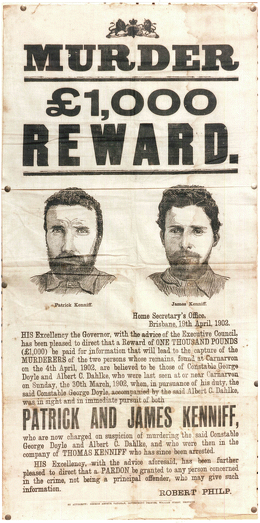

Patrick Kenniff (1863–1903) and James Kenniff (c.1869–1940) — The Kenniff brothers — are often called “Queensland’s last bushrangers”. They were the sons of an Irish-born selector from New South Wales. From a young age, both were involved in cattle duffing (the theft and illegal rebranding of livestock), setting them on a path toward bushranging. [Source: Australia Mint]

In 1893, the brothers moved to the Upper Warrego district and took up several land blocks. There they fell in with a group of known cattle thieves, stealing stock from neighbouring properties—especially Carnarvon Station, owned by Albert Dahlke. This rivalry deepened into open hostility.

When the government later cancelled the Kenniffs’ lease, the brothers turned fully to outlaw life. In 1902, police issued arrest warrants for the Kenniffs. A posse was formed to capture them, led by Dahlke and Constable George Doyle, accompanied by Sam Johnson, an Aboriginal tracker.

The posse located the brothers at Lethbridge’s Pocket, but the encounter ended violently. The Kenniffs escaped, chasing Johnson away from the scene. Soon after, the charred remains of Doyle and Dahlke were discovered, alongside evidence of a gunfight. A massive manhunt ensued, culminating in the brothers’ capture at Arrest Creek.

Their trial for murder created a sensation across Queensland. Public opinion was sharply divided—many believed the brothers had been framed or unfairly treated. Despite the controversy, both were found guilty and sentenced to death. Patrick Kenniff, maintaining his innocence to the end, was executed in 1903 at Boggo Road Gaol. Remarkably, his funeral drew over a thousand mourners, an unusual tribute for a condemned bushranger.

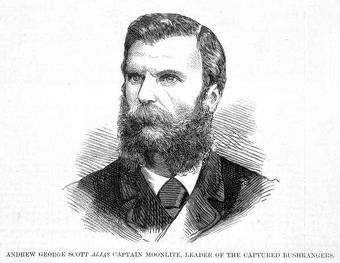

Andrew George Scott — ‘Captain Moonlite’

Andrew George Scott (1842–1880), better known by his self-styled alias “Captain Moonlite,” is remembered as one of Australia’s more romantic and tragic bushrangers, largely because of his deep affection for his companion James Nesbitt. Born in Ireland, the son of an Anglican clergyman, Scott received a good education and, in 1861, served in the New Zealand Wars against Māori forces. It was during this period that he is believed to have first been nicknamed “Captain Moonlight.” [Source: Australia Mint]

After the war, Scott migrated to Australia and, in 1869, became a lay reader at Mount Egerton in Victoria. There, he and two accomplices engineered a bank robbery, leaving behind a taunting note signed “Captain Moonlite.” Scott’s later years were marked by a string of frauds and thefts, including the passing of bad cheques and the stealing of a yacht. Arrested in 1870, he served time in Maitland Gaol—where he briefly feigned insanity—before being transferred to Pentridge Prison for a longer sentence. In Pentridge, Scott formed a close and devoted relationship with fellow inmate James Nesbitt. Upon Scott’s release in 1879, the two stayed together, assembling a small gang with three other disaffected youths from Melbourne’s streets.

In November 1879, the group raided the Wantabadgery sheep station near Wagga Wagga, holding it for two days. When police surrounded the homestead, a violent confrontation followed. Two gang members were killed—one a 15-year-old boy, the other James Nesbitt. Overcome by grief at Nesbitt’s death, Moonlite surrendered. On 20 January 1880, he and one surviving accomplice were hanged.

While in prison awaiting execution, Moonlite wrote movingly about his love for Nesbitt. He wore a ring made from Nesbitt’s hair to the gallows and asked to be buried beside him in Gundagai. His wish was ignored, and he was instead interred in an unmarked grave at Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery. More than a century later, in 1995, a group of admirers succeeded in having Captain Moonlite’s remains exhumed and reburied beside Nesbitt, finally fulfilling his last request.

Dan ‘Mad Dog’ Morgan

Mad Dog Daniel Morgan (1830–1865) was among the most feared of Australia’s bushrangers. After his death he was described as “one of the most determined and bloodthirsty of colonial freebooters”—a reputation earned through his violent and unpredictable behaviour. Little is known of his early life, though he is believed to have been born Jack Fuller at Appin, New South Wales, the illegitimate son of Irish ex-convicts. Over the years he adopted several aliases, including John Smith, Down-the-River Jack, Billy the Native, and most famously, Mad Dog Morgan. Morgan’s fearsome appearance and terrifying demeanour inspired the 1976 feature film, Mad Dog Morgan. [Source: Australia Mint]

Morgan’s criminal career began in 1854 with a series of highway robberies. By 1864, his crimes had escalated: he had shot and killed a station overseer and two policemen, prompting authorities to place a £1000 reward on his head. A reign of terror followed, during which Morgan often targeted wealthy station owners known for mistreating their workers.

His behaviour was wildly erratic. At times sadistic and cruel, he took pleasure in humiliating his victims, even resorting to torture. Yet he could also display moments of strange courtesy—after killing in cold blood, he might weep and beg forgiveness. Witnesses spoke of his violent mood swings, which added to his terrifying mystique.

Morgan’s career ended in 1865 after he held up a homestead at Peechelba, north of Wangaratta, where he demanded that the owner’s wife play the piano while he dined. The following morning, as he prepared to steal a horse, armed police ambushed him, shooting him in the back. Morgan died of his wounds five hours later, bringing an end to one of the most notorious careers in Australian bushranging history.

Kelly Gang

The infamous Kelly Gang — comprised of Edward (Ned) Kelly (1855–1880) Daniel Kelly (1861–1880) Joseph Byrne (1856–1880) and Stephen Hart (1859–1880) — is arguably Australia’s most legendary group of bushrangers. It was led by Edward “Ned” Kelly, the son of Irish ex-convict John “Red” Kelly and his wife Ellen (née Quinn). Dan Kelly was Ned’s younger brother. Joe Byrne of Beechworth and Steve Hart of Wangaratta were their close friends. [Source: Australia Mint]

The Kelly family, long at odds with colonial authorities, saw themselves as victims of police persecution and were often in trouble with the law. In 1878, following a violent altercation with a police trooper, Ned and Dan fled into the Wombat Ranges near Mansfield. There they joined forces with Byrne and Hart, forming what became the Kelly Gang. Soon after, at Stringybark Creek, the gang ambushed a police party, killing three officers. Branded outlaws, they became the targets of an intense manhunt, with a large bounty placed on their heads.

In 1880, the gang staged their final, desperate act at Glenrowan, seizing control of the town’s hotel in an attempt to derail and rob a police train. For the confrontation, they famously donned homemade armour fashioned from plough mould-boards—an image now etched in Australian folklore. When police surrounded the hotel, a fierce gun battle erupted. Byrne, Hart, and Dan Kelly were killed, while Ned, severely wounded, was captured alive.

Tried in Melbourne for murder, Ned Kelly was executed at Melbourne Gaol on 11 November 1880. His reputed final words were either “Ah well, I suppose it has come to this,” or the now-immortalised phrase, “Such is life.” The story of the Kelly Gang has become an enduring part of Australian myth and identity. To some, Ned Kelly is a folk hero and symbol of resistance, representing the defiant spirit of the underdog. To others, he remains a ruthless criminal. Whatever the interpretation, the cylindrical helmet of Ned Kelly stands today as one of the most iconic images in Australian history.

Related Articles:

NED KELLY: HIS LIFE, GANG, WRITINGS, ARMOR, DEATH AND MISSING HEAD ioa.factsanddetails.com

Moondyne Joe

Moondyne Joe

Joseph Bolitho Johns (1827–1900), better known as Moondyne Joe, was Western Australia’s most notorious bushranger, famed not for violence or robbery, but for his audacious prison escapes. Believed to have been born in Wales or Cornwall, the son of a blacksmith, Johns was transported to Western Australia in 1853 for theft. By around 1860, he had settled near Moondyne Springs, from which he later took his nickname. [Source: Australia Mint]

A habitual lawbreaker, Johns was frequently arrested for minor offences and soon developed a reputation for his defiance of authority. Between 1865 and 1867, he made four escape attempts, three of them successful. During his final breakout, he spent four months at large in the Darling Ranges, bushranging with two companions.

When he was recaptured, authorities took extreme precautions. Johns was confined in solitary within a specially reinforced cell at Fremantle Prison, fitted with triple-barred windows and heavy irons. When his health declined, he was allowed daily exercise breaking rocks in the yard. Ingeniously, he used the rock pile to conceal a tunnel, eventually digging his way to freedom in 1867—his most celebrated escape.

For the next two years, Moondyne Joe roamed the hill country east of Perth, before being captured once again in 1869 and sentenced to another year in irons for escaping custody. Finally released in 1871 and granted a conditional pardon in 1873, Johns abandoned his bushranging life and lived quietly until his death in the Fremantle Asylum in 1900.

Though he never carried out dramatic holdups or shootouts, Moondyne Joe’s relentless pursuit of freedom made him a folk hero of Western Australia. His exploits inspired John Boyle O’Reilly’s romanticised novel, as well as later films, books, and poems. Today, the township of Toodyay celebrates his legacy each year with the Moondyne Festival.

Birdman of the Coorong

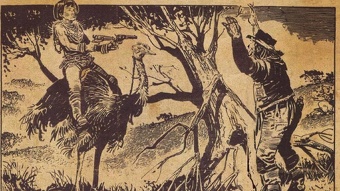

John Francis Peggotty (1864–1899) — the “Birdman of the Coorong” — is best known as the central character in one of the strangest Australia’s bushranger stories, which took place at The Coorong, at the mouth of the Murray River. According to the story, Peggotty was born in Ireland in 1864, a premature baby who never grew larger than a seven-year-old child. At some point he travelled to South Africa, where he is said to have learned to ride ostriches. Fond of gold and jewellery, Peggotty allegedly developed a talent for chimney climbing and burglary, for which he served five years in prison in England before emigrating to Australia. Settling first in Adelaide, he soon returned to a life of theft.

By 1898, Peggotty had moved to the Coorong region of South Australia, where he took to the bush and became a bushranger unlike any other. Travellers reported being held up by a tiny, bearded man riding an ostrich, stripped to the waist, laden with gold chains, and armed with two small ornate pistols. At first, the authorities dismissed such accounts as nonsense—until the body of a man was found surrounded by large bird tracks. In 1899, police patrols claimed to have sighted Peggotty and his ostrich; when they opened fire, the bird reportedly sprinted away over sand dunes their horses could not climb.

Peggotty is said to have committed a dozen robberies and at least one murder before his dramatic end later that year near Meningie. A gunman shot him and killed his ostrich with a single shot to the head. The headless bird bolted across the dunes with Peggotty clinging on. When the carcass was found days later, Peggotty himself had vanished—believed to have crawled away to die, taking with him a fortune in stolen gold and jewels.

Legend holds that the Birdman’s body still lies buried somewhere beneath the sands of the Coorong, his treasure yet to be found. Though the story’s truth has never been proven, it endures in South Australian folklore, and the town of Meningie commemorates the tale with a statue of an ostrich fitted with a saddle—a tribute to one of Australia’s strangest bushranging legends.

Frederick Ward — Last of the Professional Bushranger

Frederick Ward (1835–1870), also known as "Captain Thunderbolt," was the last professional bushranger in New South Wales, as well as one of the most successful. Due to his gentlemanly behavior and tendency to avoid violence during his bushranging escapades, he generated much support and sympathy. A highly skilled horseman, Ward's strong self-reliance and physical endurance enabled him to survive in the wilderness for extended periods. [Source: State Library, New South Wales]

Ward was born in Windsor, New South Wales (NSW). As a young man, he worked as a horsebreaker and drover on the Tocal Run on the lower Paterson River, where he acquired extensive knowledge of horses. He was first arrested in April 1856 for attempting to drive forty-five stolen horses to the Windsor sale yards. Found guilty, he served four years' imprisonment at Cockatoo Island before being released on a ticket of leave. In 1856 he was arrested for stealing horse and received a ten-year sentence of hard labor on Cockatoo Island.

In September 1863, Ward and another prisoner, Fred Britten, escaped Cockatoo Island by swimming to the mainland, presumably to the northern peninsula of Woolwich. They then headed north out of Sydney. Traveling toward New England and then Maitland, Ward began committing a series of robberies. According to bushranger lore, Ward earned the nickname "Captain Thunderbolt" when he startled a customs officer asleep in a tollbar house on the road between Rutherford and Maitland by banging loudly on the door. The startled officer, Delaney, purportedly remarked, "By God, I thought it must have been a thunderbolt."

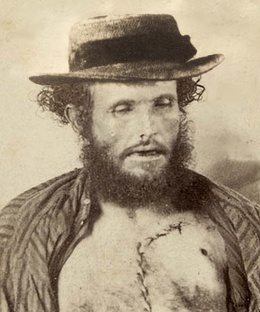

Adopting the alias "Captain Thunderbolt," Ward embarked on a bushranging career spanning much of New South Wales, from the Hunter Valley to the Queensland border. He was known for his gallantry, cunning, and restraint but was eventually shot by Captain Walker, an off-duty policeman, in 1870 after a dramatic showdown in which Walker shot Thunderbolt’s horse out from under him in swampland near Uralla. Ward's body was taken to the Uralla courthouse, where the Armidale photographer Mr. Cunningham took a portrait. The photograph sold for one shilling per copy. The body was also placed on public display, and hundreds came to observe the famous bushranger in death.

Captain Thunderbolt and The Captain's Lady

Frederick Ward and his partner Mary Ann Bugg (1834–1905) were known as "Captain Thunderbolt," and "The Captain's Lady." They were arguably Australia's most famous bushranging couples. Their exploits in the early 1860s made them legendary figures in New South Wales folklore. Ward met Bugg in 1860. She soon became pregnant with his child. He settled her in the Dungog area before got into trouble with the authorities for violating his parole and stealing horses and sentenced to 10 years at Cockatoo Island. After he escaped [Source: Australia Mint]

Bugg was born at the Berrico outstation in New South Wales. She was the daughter of a convict and his Aboriginal wife. Her childhood was unsettled; she was moved frequently under government efforts to "integrate" Aboriginal children into European society. As a young woman, she worked as a domestic servant and was briefly married before meeting Ward.

Bugg—resourceful, intelligent, and fiercely loyal—was a vital part of the operation. She acted as a scout, lookout, and supplier and was renowned for her ability to ride and shoot as well as any man. She often dressed in men's clothing to travel unnoticed, earning her the nickname "The Captain's Lady."

Ward roamed across a vast area of New South Wales, from the Hunter Valley to the Queensland border. Sometimes he was accompanied by Bugg and their children. From November 1863 to January 1864, the entire bushranging family went on a spree in Dungog, Stroud, and Singleton. They were pursued by police and volunteers in the rugged hill country near Dungog, but Ward, Bugg and the children escaped. Thunderbolt evaded his pursuers by leaping down a cliff face above the Allyn River. Fortunately for the horse, they landed in a sandy area.

By the time Thunderbolt’s long run came to an end in 1870, Mary Ann had settled in Mudgee, where she lived quietly and raised her fifteen children, the last of whom was born in the 1870s. Today, the legend of Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady endures in films, songs, and literature, as well as in a statue at Uralla and a famous painting by Tom Roberts, celebrating the story of Australia’s “gentleman bushranger” and the remarkable woman who rode beside him.

Governor Brothers — Last Proclaimed Outlaws of New South Wales

Jimmy Governor (1875–1901) and Joe Governor (died 1901) were the last proclaimed outlaws in New South Wales, and were responsible for what became the largest manhunt in Australian history. Governors were Aboriginals. They were raised in Gresford, Paterson, and Vacy, but, like many Aboriginal families in the early 1890s, they were moved onto reserves. Joe and Jimmy, along with their father Tommy, worked as cattlemen and horse-breakers on stations along the Paterson River and Allynbrook, including the Boydell property. [Source: State Library, New South Wales]

In 1896, Jimmy joined the New South Wales Mounted Police as a tracker, stationed at Cassilis for a year, but left frustrated by lack of advancement and tensions with colleagues. Two years later, in December 1898, he married 16-year-old Ethel Page, a union controversial at the time due to prevailing attitudes toward interracial marriage. The couple moved to Breelong in the Gilgandra region, where Jimmy worked as a fencing contractor and Ethel as an unpaid maid for the Mawbey family. Disputes over rations, unpaid work, and racial slurs escalated tensions.

On 20 July 1900, Jimmy, accompanied by Joe, Ethel, and a friend, Jack Underwood, confronted the Mawbey family. While negotiations with Mr. Mawbey ended peacefully, Jimmy later attacked Mrs. Mawbey and the family’s teacher, Ellen Kerz, who, along with two girls, attempted to flee. In the ensuing violence—later called the Breelong Massacre—five people were killed and one seriously wounded.

News of the massacre spread quickly, prompting a massive search. Ethel fled to Dubbo with her baby, while Underwood was captured. The Governor brothers remained on the run for three months, evading around 2,000 police and civilians across 3,000 kilometres of northern New South Wales—the largest manhunt in the nation’s history. During this period, Jimmy took revenge on perceived enemies, travelling through the Goulburn River region and targeting former employers. Despite being heavily pursued, the brothers relied on Jimmy’s tracking skills and knowledge of police tactics to stay ahead, even committing over 80 crimes, including the rape of a 15-year-old girl. By October 1900, the NSW legislature officially declared them outlaws, raising the reward for capture to £1,000.

The end came in late October. While crossing a river, the brothers became separated. On 27 October, Jimmy—severely wounded—was surrounded by armed locals near Gresford, including members of the Moore family. After a brief chase, he was captured. Joe survived a few days longer, but on 31 October, he was found asleep in a gorge near St Clair and shot at close range by a local grazier. Jimmy was transferred to Sydney and, on 19 November 1900, was arraigned at the Central Criminal Court for the murder of Ellen Kerz. Extensive evidence, including testimonies from Ethel Governor and George Mawbey, was presented. Jimmy provided detailed accounts of the Breelong Massacre and his months on the run. Found guilty, Jimmy was sentenced to death by hanging, which took place at Darlinghurst Gaol on 18 January 1901.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! Australia, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025