WAKA — MĀORI CANOES

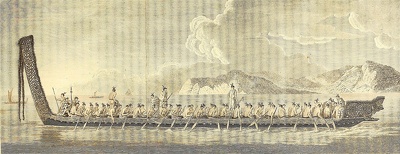

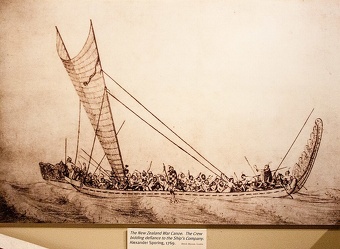

Māori waka with triangle sail drawn by Herman Spöring during Cook's first voyage to New Zealand in 1769

Large Māori canoes are doubled hulled vessels with elaborate carvings and feathers hanging along the waterline. A 120-foot Māori war canoe can hold 150 people and is steered with two rudder-like devices guided by two people at the stern. There are smaller versions too, New Zealand’s abundance of wide-girthed trees such as totara meant that Māori could build much more diverse canoes than in their Polynesian homeland. They developed a variety of vessels for coastal and inland waterways. Each had its special function, from the grand carved waka taua for war parties, to handy rafts for fishing.

Māori canoes are called waka. Both men and women paddle the canoes (but usually men do it). During traditional ceremonies, when a canoe is brought ashore it is welcomed by tattooed men in flax skirts who blow conch shells and do a haka. Among the greatest Māori works of art are Tauihu (canoe prows). One from Late Te Puawaitanga or early Te Huringa I period (1500–1900), attributed Ngati Toa, is from the lower North Island and is made of wood and paua shell. At the tauihu's top is the peaked head and protruding tongue of a human form. Two large carved spirals behind the head represent the parent deities of the Māori creation story, Ranginui (the sky father) and Papatuanuku (the earth mother). These tauihu became tribal heirlooms, passing from generation to generation. [Source: Māori Treasures from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tokyo National Museum, Heiseikan Special Exhibition Gallery 1 & 2, January — March 2007]

The significance of waka (canoes) for Māori has its roots in times past when waka voyaging forged links between Hawaiki, the ancestral homeland, and New Zealand, the cradle of Māori culture. According to legend, Maui, a god-like ancestor, traveled by waka into the Southern Ocean and fished up the North Island, which is known as Te Ika-a-Maui (Maui's Fish). The South Island became his waka, Te Waka-a-Maui (Maui’s canoe). The human ancestor Kupe is said to have discovered New Zealand later on during a waka voyage. His wife, Kuramarotini, is credited with naming the land Aotearoa, meaning "long white cloud" in Māori, the name now used for New Zealand. Many stories recount the subsequent arrival of various tribes' ancestors on numerous waka at important landing sites. Today, Māori trace their descent from the ancestors who arrived on these waka and from the founding ancestors of iwi (tribe) and hapu (subclan. [Source: Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

There is a lot to be said about Māori canoes. They are important in history, culture and art as well as serving as a means of transportation. The information here come mostly from an article by Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr in the Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand teara.govt.nz

RELATED ARTICLES:

MĀORI: POPULATION, LANGUAGE, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CUSTOMS: ETIQUETTE, THE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE IN THE PACIFIC REGION, POLYNESIA AND MELANESIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, CHRISTIANITY, CEREMONIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL MĀORI BUILDINGS, VILLAGES AND HOMES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI TATTOOS: HISTORY, HOW THEY WERE MADE, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI GOVERNMENT: KING, QUEEN, POLITICS, CHIEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MĀORI: ORIGIN, ARRIVAL IN NEW ZEALAND, LIFE, WARFARE

ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI AFTER THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

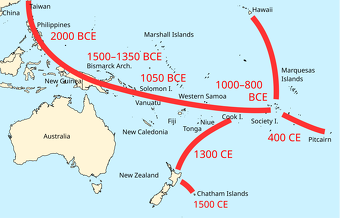

Seven Waka and Maori Beliefs About Their Origin

All Māori believe they are descendants of people who arrived on seven great canoes that came from the mother island of Hawaiki in A.D. 1350. Hawaiki is most likely Tahiti or one of the Cook Islands.

According to Māori legend, New Zealand was created by the demigod Maui, who persuaded his brothers to sail to unknown waters south of their homeland on a fishing trip. Using his mother's jawbone for a hook and his own blood for bait, Maui caught a colossal fish (the North Island of New Zealand).

The Māori settled primarily on the North Island of New Zealand, which they called “Te Ika a Maui” (the Fish of Maui). The South Island is referred to as both “Te Wai Pounamu” (the Water of Jade) and Maui's canoe.

Adele Whyte, the Tuapapa Putaiao Māori Fellow at Victoria University in Wellington, said: "The story I was told when I was growing up is that there was a fleet of seven great waka (canoes) that came to New Zealand," she said. "Every tribe knows which waka their ancestors arrived in. My ancestors were in a waka called Takitimu. There might have been 20 people travelling in a canoe the size of a waka. Seven waka, that's about 140 people. And if, as we think, about half or 56 of these people happen to be women, it does

Ocean-Going Canoes That Brought the Māori to New Zealand

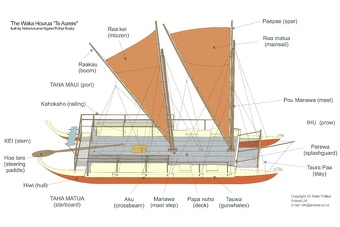

The exact details of the voyaging waka are unknown, but traditional Pacific canoes provide valuable clues. Their design and construction were shaped by the purpose of the vessel and the materials available. On many Pacific islands, where trees were small, canoe-building techniques were gradually refined over time. Simple dugout logs evolved into vessels fitted with outrigger floats for stability. Planks were added to the gunwales—the upper edges along each side—to raise the hulls higher above the waterline, improving seaworthiness. [Source: Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

The introduction of sails enabled canoes to travel further and faster under favourable conditions. Eventually, two hulls were lashed together to form double-hulled vessels capable of carrying larger numbers of people and cargo across vast ocean distances.

It is likely that ancestral voyaging canoes could both sail and be paddled, and that they carried enough food and water for voyages lasting a month or more. Experimental voyages in modern times have demonstrated that the journey from Rarotonga to New Zealand could take between two and three weeks. Māori ancestral waka were most likely large outrigger canoes or double-hulled vessels.

Double-hulled waka were observed during Abel Tasman’s voyage to New Zealand in 1642. Later, Sydney Parkinson, an artist on James Cook’s first expedition in 1769, and the German scientist Johann Reinhold Forster, who sailed with Cook in 1773, described waka fitted with outriggers (known as ama, amatiatia, or korewa). However, little detailed information exists on Māori outrigger canoes.

Although 19th-century ethnographers recorded double-hulled canoes being used as fishing platforms, there are no known accounts of such vessels undertaking long voyages or expeditions. Even during Cook’s time, double hulls were uncommon in the North Island, though still relatively numerous in the South Island. They gradually fell out of use during the 19th century, first disappearing from the North Island. The last examples appear to have been single-hulled canoes temporarily lashed together rather than purpose-built double hulls. The double hull was revived in the early 1990s with the construction of Te Aurere of Te Tai Tokerau (Northland), marking a return to traditional voyaging methods and technologies.

Related Articles: FIRST PEOPLE IN THE OCEANIA AND THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com ; EXPANSION OF PEOPLE ACROSS THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com

Waka Used Around New Zealand

As Māori tribes developed and grew, there was a corresponding change in waka culture. Descended from people who had lived on small Pacific islands—where land was scarce and survival often depended on the sea—they now occupied a land of vast forests and abundant natural resources. The need to build vessels capable of navigating long ocean voyages diminished, and canoe design, construction, and use adapted to new environmental conditions. [Source: Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

In Aotearoa, waka became predominantly single-hulled vessels, classified according to their size, shape, adornment, and purpose. These features were determined largely by the types and availability of native trees. On many Pacific islands, the narrow girth of local trees limited the beam (width) of a canoe. Builders were therefore compelled to construct narrow hulls and build up the sides to raise the freeboard, which often resulted in instability. To counter this, they attached an outrigger float with crossbeams to the hull.

In contrast, New Zealand’s forests provided trees of great size—such as tōtara, kauri, māngeo, rimu, kahikatea, and mataī—from which canoes of ample beam could be fashioned. With raised top strakes (planks running from prow to stern) attached to the gunwales, these canoes remained highly stable without the need for an outrigger. Tōtara, being light, durable, and widely available, became the most common material, while kauri was favoured in the north.

Canoes were now built for rivers, lakes, and coastal waters, rather than for transoceanic voyages. As a result, new types of waka became central to Māori life, including the waka taua (war canoe), waka tētē (canoe with a carved figurehead), waka tīwai (dugout canoe), mōkihi (reed raft), and the modern waka tangata (ceremonial canoe).

Making a Māori Canoe

Selecting a Tree: Trees were chosen for their strength, straightness, and length. Once selected, a tree was taunahatia (bespoken for use), and a clearing was made around it. Such a tree might remain standing for several years before felling. A karakia (incantation) was often recited to protect it from being toppled by Tāwhirimātea, the god of winds. [Source: Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Before felling, several factors were carefully considered—the location, the probable fall direction, any obstacles that might break the fall, and the practicality of moving the tree once it had fallen. A tohunga (expert or priest) would then perform karakia to remove tapu (sacred restriction) and to appease Tāne, the god of the forest. When the tree was finally felled, tapu was reinstated to ensure continued spiritual protection.

Construction: Each working day began with the imposition of tapu upon the craftsmen, which was lifted again at nightfall. The builders roughly hollowed out the trunk near where it fell, before hauling the hiwi (hull) to a more suitable working site. Dressed and carved timber was then added for the rauawa (topstrakes), increasing the freeboard and improving the waka’s seaworthiness.

When construction was complete, elaborately carved components—the tauihu (prow carving) and taurapa (sternpost)—were fitted to the ihu (bow) and kei (stern). A kawa ceremony (to remove tapu) was performed to make the vessel ready for use, followed by the recitation of a karakia at the moment of launching.

Waka Taua — Large War Canoes

Waka taua were the largest of all Māori canoes, ranging in length from about nine to over thirty metres. Some were capable of carrying as many as one hundred people, as observed by James Cook during his 18th-century voyages, and later confirmed by other witnesses in the 19th century. These canoes were also the most elaborately carved and decorated. They were sometimes referred to as waka pītau, a name derived from the perforated spiral carving (pītau) that supports the figurehead on the tauihu (prow). [Source: Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Named for their association with taua (war parties), these vessels were used to transport warriors on military expeditions and raids. As such, they were deeply connected with the outcomes of war—death, loss, and the return of the fallen. On occasion, waka taua carried home the remains of men slain in battle, endowing the vessel with enduring spiritual significance. Many tribes maintain strict rituals governing the construction, launching, and use of their waka taua.

The historian Hoani Nahe recalled two Ngāti Maru waka taua—Ōtuiti and Ōkūnui—in the late 19th century, describing them as the largest he had ever seen. Each could hold five ranks of men stretching from bow to stern, where three men were seated, two of whom would alternate with paddlers as they tired. The hulls were often built from three sections joined with haumi (mortise-and-tenon joints) and securely lashed together, creating strong, flexible vessels suited to New Zealand’s waterways.

Types of Waka

Waka Tīwai, also known as waka kōpapa, were probably the most common and numerous of all Māori canoes. They were formed from a single hollowed-out log, without gunwales, carvings, thwarts, or separate bow and stern pieces. Generally shorter and narrower than the waka taua and waka tētē, they were ideal for transporting small groups of people and their belongings along rivers and across harbours. Tribes living near waterways used them regularly for travel and everyday tasks.

Waka tīwai were also used for recreation and continue to feature in regattas today, particularly in the Waikato region, where regular racing series are attended by many local schools. The canoes were sometimes called waka peke (“leaping canoes”), because during some regattas competitors raced by jumping their canoes over logs raised just above the water surface. This activity, often described as canoe hurdling, was last practised at the Tūrangawaewae Regatta in the early 1990s. [Source: Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

East Coast Mōkihi (Rafts): The nineteenth-century Ngāti Porou leader Tuta Nihoniho described a form of mōkihi (raft) built by his people for inshore fishing. Also known as amatiatia (outriggers), these craft were made from buoyant woods such as whau or houama, fastened together with mānuka pins. A second layer of smaller timbers was placed over the main frame, and the structure was bound securely with kareao (supplejack vine). Two floats were typically placed about one metre apart and joined by three or four crossbeams. Two people would sit astride the craft—one on each side—and paddle. These rafts were used primarily for fishing and for setting and retrieving crayfish traps.

South Island Mōkihi, (also called moki) were constructed differently, using raupō (bulrush) and harakeke (flax) to accommodate different challenges presented by the South Island. They existed in two main forms. The simpler type consisted of a single bundle of dry bulrushes or flax flower stalks on which a person could sit, paddling with their hands or a short piece of wood. The larger, more elaborate form was made by lashing several bundles together to resemble a canoe. These rafts were used to transport people and goods along inland waterways. Although less durable than canoes made from tōtara or kauri, they were quick to build, required only local materials, and provided an effective temporary means of transport, especially where timber was scarce.

Moriori Waka were used by the Moriori people of Rēkohu (Chatham Islands), about 800 kilometres east of mainland New Zealand. There were four main types of waka: waka pūhara, waka rimu, waka pahi, and waka rā. These are often described as rafts rather than true canoes, largely because the Chatham Islands lacked trees large enough to produce dugout hulls. Despite this, when properly assembled, these vessels were sturdy, buoyant, and remarkably safe—capable of carrying over fifty people.

Waka Pūhara, also known as korari, had two keels made from poles or small beams and a flat bottom. The sternpost (koua in Moriori) and puremu (two projecting pieces of wood at the stern) were carved, while the bottom and sides were formed from the dry flower stalks of flax. Inflated kelp was stored in the base to increase buoyancy. Waka Rimu were similar in construction, except that the sides and base were covered entirely with sheets of bull kelp (rimurapa), giving the vessel excellent flotation.

Waka Pahi were a deep-water vessel used for journeys to the outlying islands. Built on two matipou keels up to nine metres long, they featured a sternpost made from akeake wood that could exceed three metres in height, with a slightly shorter puremu. Bull kelp was again used for flotation, making the vessel seaworthy for open-water travel.

Waka Rā was constructed from bracken stems and flax stalks,and resembled the South Island mōkihi but had a more ceremonial role. The sides were low, and instead of people, carved human figures were placed inside, each holding a paddle. The waka was then set adrift as an offering to Rongotakuiti, a deity representing seals and blackfish, to ensure an abundance of marine food resources.

Waka Tete

The waka tete (also known as the waka pakoko) was generally shorter and simpler than the large waka taua. Some were constructed from single logs, while others had joints similar to those of the waka taua. The basic components were the same for both types of waka: the hull, gunwales, thwarts, bow piece, and stern post. Gunwales were usually undecorated, and the bow piece and stern post were less intricately carved. The bow piece typically took the form of a stylized face with a protruding tongue. This feature is described as tete or pakoko, by which the vessel is classified. [Source: Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

These canoes were used in many ways and were not subject to as many ritual restrictions as waka taua. They carried goods, produce, and people along many coastal and inland waterways. Early settler records describe the crowded Auckland waterfront of the mid-1800s with these waka laden with wares for trade.

A late 20th-century development is the construction of canoes for educational purposes. Known as waka tangata, these canoes are very similar to waka tete, with uncarved gunwales and simple ornamentation on the stern posts. Free from the religious restrictions many tribes associate with waka, they can be used by everyone — waka tangata means "the people's canoe."

Waka Equipment

Paddles: Paddling was the most common method of propelling waka. The paddle was known as a hoe or hirau, while longer paddles were called hoe whakatere, hoe whakahaere, or urungi. They were usually made from kahikatea wood, though mataī was also valued for being both light and strong. According to Tuta Nihoniho of Ngāti Porou, paddles could also be fashioned from mānuka, maire, the heartwood of pukatea, or tawa. [Source: Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

The steering oars were straight, whereas the blades of regular paddles were set at a slight angle. The face of the blade used for pushing against the water was flat, while the reverse side was rounded. Handles were typically straight, although in the Waikato district curved handles were sometimes used. Most paddles were unadorned, but some were painted with scrolled kōwhaiwhai designs, and ceremonial paddles were often elaborately carved. On coastal voyages, one man usually acted as steersman. However, on long ocean journeys, up to four men might steer—two positioned at the stern and two near the bow.

Sails: Triangular rā (sails) were occasionally used. They were usually made from the light leaves of raupō (bulrush), though harakeke (flax) or kareao (supplejack) could also be used. The sails were often attached to a main mast with a sprit, allowing them to be extended or retracted. Another type, the rā kaupaparu, was mounted on a short mast with two booms, though it is unclear whether this design was indigenous or introduced. Usually a single sail was carried, but larger waka could use two or even three.

Poling or Punting: On rivers, waka were often propelled upstream using a toko (pole). Poling required great strength and endurance, giving rise to the saying: “He waka tuku ki tai, tururu ana ngā tāngata o runga; he waka toko, tau ana te kōhakoha.” (When a canoe drifts downstream, those aboard crouch in ease; with a poled canoe, expect exertion.)

Anchors were known as punga. The main stern anchor was called punga whakawhenua, while the smaller bow anchor, punga karewa, was lowered to steady the vessel in rough seas. A lighter stone, the punga terewai, though not strictly an anchor, was used for sounding depths and determining currents. Anchors were made from stones by various methods. A rope might be passed through a hole bored in the stone or wrapped around a narrowed middle section. In other cases, a stone was enclosed in a net of flax or vines, or several stones were placed together in a basket. Long, thin stones could be lashed to two sticks bound in the form of a cross.

Bailers: In waka fitted with a floor or decking, designated bailing wells were known as puna wai or tainga a wai. A person was usually assigned to each well, though sometimes two would bail from the same one. Bailers—known variously as tata, tiheru, or tā wai—were made from several types of wood and were often carved with decorative designs.

Māori Reject Call to Bring Lifejackets on Their Waka

In 2000, the New Zealand Herald reported: After three waka accidents — one fatal — Māori were divided over whether lifejackets should be carried on the ceremonial war canoes. Hec Busby, captain of the Waitangi waka which came to grief on New Year's Eve, says that if carrying lifejackets is made compulsory, the great canoe will never be used again. He received support from Māori cultural expert Dr Pita Sharples, who was "definitely not in favour of lifejackets" being worn on ceremonial or spiritual occasions. "The physical dress is totally interwoven with the cultural and spiritual essence of the occasion," he said. [Source: Tony Stickley, New Zealand Herald, June 29, 2000]

Nor did he want lifejackets stowed on board the craft, preferring better education in reading weather and water conditions. In "traditional times" the waka would not go out if the weather turned nasty, and the same should apply today, he said. Lifejackets could be worn when crews were training in the war canoes in rough weather. In ancient times, Māori canoeists had a much greater affinity with the sea and were more physically able to survive. They also used gourds as flotation devices.

But other prominent Māori favour having lifejackets on board the traditional vessels, even on special occasions. The Minister of Māori Affairs, Dover Samuels, supported having "some form of lifejacket" on the waka, whether during practice or on ceremonial occasions when kuia, kaumatua or children might be on board. Waka ceremonies had cultural significance, he said, but "at the end of the day we can't trade that off against loss of life."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New Zealand government, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Live Science, Natural History magazine, New Zealand Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! New Zealand, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025