Home | Category: Animals / Marsupials

BILBIES

Bilbies are long-eared desert-dwelling marsupials omnivores that eat both plants and animals. They belong to the Macrotis genus and are also known as rabbit-bandicoots. Members of the order Peramelemorphia, bilbies are very rare and found primarily in Australia’s Northern Territory. They are small and have rabbit-like ears. The Australia government has promoted "Easter bilbies" as a homegrown alternative to Easter bunnies.

At the time of European arrival in Australia in the late 18th century there were two species. The lesser bilby became extinct in the 1950s; the greater bilby survives but is endangered and is currently listed as a vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The decline of bilbies has been mostly attributed to by habitat loss and predation and competition by cats, foxes, and other introduced species. They now only exist in a handful of remote regions in Western Australia, Queensland, and the Northern Territory. [Source: Annie Roth, National Geographic, April 18, 2019]

Australian scientists have found that bilbies glow under ultraviolet light. University of Kansas biologist Leo Smith, an expert in biofluorescence, told NPR it was not clear what purpose the trait served in mammals. “It’s not something that you can necessarily come up with a really good explanation for why it might be there or what could be the advantage. Like a lot of things just evolve and they’re not good or bad, they’re just whatever,” Smith said.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BANDICOOTS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BANDICOOT SPECIES IN SOUTHERN AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BANDICOOT SPECIES IN NORTHERN, EASTERN AND WESTERN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

POSSUMS OF AUSTRALIA AND NEW GUINEA: SPECIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BRUSHTAILED POSSUMS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SPECIES, PESTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

GLIDERS OF AUSTRALIA AND NEW GUINEA: MARSUPIAL EQUIVALENTS OF FLYING SQUIRRELS ioa.factsanddetails.com

GLIDER SPECIES (SUGAR, MAHOGANY, GREATER, YELLOW-BELLIED): CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSCUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSCUSES OF SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

Easter Bilbies and Bilby Conservation

Bilbies have been popularised as a native alternative to the Easter Bunny by selling chocolate Easter Bilbies. Haigh's Chocolates in Adelaide made 950,000 chocolate bilbies between 1993 and Easter 2020, with proceeds donated to the Foundation for Rabbit-Free Australia, which does environmental work to protect the indigenous biodiversity of Australia. A National Bilby Day is held in Australia on the second Sunday in September to raise funds for conservation projects. Wall Street Journal Wikipedia]

Annie Roth wrote in National Geographic: Australian conservation groups such as the Foundation for Rabbit-Free Australia and Save the Bilby Fund have encouraged public awareness of the species by promoting the Easter bilby as an alternative to the Easter bunny. Although the campaign has seen a number of successes, including mass production of Easter Bilby chocolates, conservationists should up the ante. [Source: Annie Roth, National Geographic, April 18, 2019]

The new research has made Kevin Bradley, CEO of Save the Bilby Fund, more determined to conserve the species.“If we save the bilby, we will also be saving many other [species] that are less charismatic but none the less important. Australia has an appalling extinction record, and I am determined to not let the bilby join this list on my watch,” Bradley says. Bradley isn’t alone: The Australian government released a preliminary version of their latest bilby recovery plan, which outlines plans to improve the country’s control of invasive species, restore bilby habitat, and promote management of the species through partnerships with Aboriginal communities.

However, it may be several years before these plans are implemented. In the meantime, Australians who care about the bilby and other native species should continue celebrating it — even beyond Easter, says Sally Box, Australia's Threatened Species Commissioner. The Easter campaign “is a fantastic initiative to help improve awareness around the plight of the bilby,” Box said, “and can lead to Australians taking greater action to protect it.”

Extinct Lesser Bilbies

Lesser bilbies (Macrotis leucura) are now extinct. Also known as yallara, lesser rabbit-eared bandicoots and white-tailed rabbit-eared bandicoots, they don’t seem to have been that common except for in a few remote places. After their discovery in 1887, they were rarely seen or collected and remained relatively unknown to science until 1931, when Hedley Finlayson encountered many of them near Cooncherie Station in the northeastern part of South Australia. He collected 12 live specimens and said the animal was abundant in that area, but these were the last lesser bilbies to be collected alive. [Source: Wikipedia]

Lesser bilbies lived in grassland, shrub grasslands and sparsly-vegetated deserts in the Gibson and Great Sandy deserts of arid central Australia and northeast South Australia and adjoining southeast Northern Territory in the northern half of the Lake Eyre Basin. Their populations are believed to have declined drastically mainly as a result of predation by introduced foxes, and competition with introduced rabbits for forage and burrows. Natural predators included birds of prey, monitor lizards, and predatory marsupials. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Extinct. [Source: Angela Singh, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The last specimen ever found was a skull picked up below a wedge-tailed eagle's nest in 1967 at Steele Gap in the Simpson Desert, Northern Territory. The bones were estimated as being under 15 years old. Indigenous Australian oral tradition suggests that this species possibly survived into the 1960s. In addition to introduced animals, changes in the fire regime and the degradation of habitat have all been blamed for the extinction of lesser bilbies. However, Jane Thornback and Martin Jenkins wrote in the 1982 IUCN mammal red data book that the vegetation in the main part of the animal's range remained intact, with little evidence of cattle or rabbit grazing, and point to cats and foxes as the most likely cause of the extinction of the lesser bilby.

Lesser Bilby Characteristics and Behavior

Lesser bilbies ranged in weight from 300 to 1600 grams (10.57 to 56.39 ounces), with an average weight of 354 grams (12.48 ounces). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) was present: Males are larger than females. The body and head length of males was 36.5 to 44 centimeters (14.4 to 17.3 inches); for females, 32 to 39 centimeters (12.6 to 15.4inches) . Lesser bilbies had long tails, ranging from 11.5 to 27.5 centimeters (4.5 to 10.8 inches) in length, Lesser bilbies had very long, pointed, rabbit-like ears. Their back and sides were usually light gray, and their underparts and tail were white. A gray line extended to the rear of the body. Lesser bilbies had unique feet. The front feet were comprised of three stout toes with curved claws, and two very small toes. Their hind feet possed only three toes. The first toe is made up of the fusion of digits two and three, the second toe (digit 4) was very large, and the last toe (digit 5) was an average size; the first digit was missing. The pouch of females opened downwards and backwards. [Source: Angela Singh, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Lesser bilbies were solitary, terrestrial, nocturnal desert mammals that were mostly active at night. Unusually, they slept sitting up by squatting on their hind legs, with their snout tucked between their legs and their long ears folded over their eyes. Lesser bilbies had poor eye sight and relied on their keen senses of smell and hearing to capture food. They were are omnivores (ate a variety of things, including plants and animals), feeding mainly on ants, termites, beetles, larvae, seeds, fruits, and fungi. They didn’t need to drink water; the obtained enough of it from the insects, fruit and seeds they ate. As food was scarce in their desert habitat female lesser bilbies may have eaten their young to survive. A home range occupied by a female, male, and their young.

Their dens were a network of spiral tunnels in sand dunes. These tunnels were about three meters (10 feet) in length and one and a half meters (five feet) deep. The opening of the tunnels was concealed to prevent predators from entering. Unlike greater bilbies, lesser bilbies were described as aggressive and tenacious. Finlayson wrote they were "fierce and intractable, and repulsed the most tactful attempts to handle them by repeated savage snapping bites and harsh hissing sounds". This species would not reside in the deep and narrow part of its burrow in cooler seasons, remaining a short distance from the entrance; this habit was exploited by hunters who would collapse the tunnel behind their prey to force it toward the soft sand covering the opening of the burrow.

Lesser bilbies bred between the months of March and May. Their gestation period was 21 days. Litters arged in size from one to three young, which remained in the pouch for 70 to 75 days where they were attached to one of the mother's nipples from which they suckled milk. Fourteen days after leaving the pouch young began to be weaned. Mating occured again 50 days after a litter is born.

Greater Bilbies

Greater bilbies (Greater bilbies) are also known as rabbit-eared bandicoots and bilbies. They have a head and body length of around 55 centimeters (22 inches). Their tail is usually around 29 centimeters (11 inches) long. The fur is usually grey or white and and they a long, pointy nose and very long rabbit-like ears. They are desert-dwelling creatures that once occupied over 80 percent of the Australian mainland

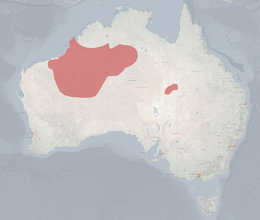

Greater bilbies were historically found throughout South Australia, Western Australia, the Northern Territory, and New South Wales. Small populations were also found in southwestern Queensland. Upon the introduction of feral cats and red foxes and rabbits by Europeans, the home range of Greater bilbies shrunk dramatically to 20 to 30 percent of their original range. Now they are found in the Great Sandy, Tanami, and Gibson deserts in northwest Australia and the south west tip of Queensland. They are now considered extinct in South Australia. Reintroduction programs have begun in southern South Australia, southwestern Queensland, western New South Wales, and areas of Western Australia with some success due to the addition of predator-proof enclosures and intense monitoring of reintroduced populations. [Source: Emily Brown, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Greater bilbies are commonly found in arid, hot areas including deserts, dunes, and grasslands. There are three main vegetation types commonly associated with bilby habitat. 1) tussock grassland commonly found on the hills and uplands, 2) mulga woodlands and shrublands, and 3) hummlock grasslands found on dunes and sandy plains. Greater bilbies are fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing) and found in areas of rocky and clayey soil that are good for making burrows and tunnels in.

Greater Bilby Characteristics and Diet

Greater bilbies range in weight from 0.6 to 2.5 kilograms (1.2 to 3.3 pounds) have a head and body length of 29 to 55 centimeters (11.42 to 21.65 inches). Their average basal metabolic rate is 2.4 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are twice as large as females. Males weigh 0.8 to 2.5 kilograms (1.9 to 3.3 pounds) and females weigh 0.6 to 1.1 kilograms (1.2 to 2.3 pounds). Males also have enlarged foreheads and longer canines The longest-living greater bilby in captivity lived about 10 years, although six to seven years of age is generally considered the maximum lifespan in captivity. The lifespan of greater bilbies in the wild is unknown. [Source: Emily Brown, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Greater bilbies are known for their large, relatively hairless, rabbit-like ears, and long pointed snouts with sensory vibrissae and a hairless pink nose. Their fur is soft, silky and bluish grey in color with a mix of fawn over the majority of the body. The belly is covered in white or cream fur. The first part of the tail is the same bluish grey as the body with the remainder of it being black and the final 40 percent being pure white. The pouch of females opens to the rear so as to avoid filling with dirt when the animal is burrowing. The forelimbs are strong and consist of three clawed digits and two clawless digits. Greater bilby hind limbs are slender and similar to those of kangaroos. Rather than hopping, bilbies use their legs to gallop around the desert. Their tongues are long, sticky, and slender, making it easy to catch termites. The ears of greater bilbies help dissipate hear and are used to help regulate body temperature.

Greater bilbies are opportunistic omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). Among the plant foods they eat are seeds, roots, tubers seeds, grains, nuts fruit. They also consume fungus. Animal foods include insects, non-insect arthropods such as spiders, mammals, reptiles, eggs and mollusks. Greater bilbies do not drink water, they obtain water from their food. Their diet consists primarily of seeds, especially those of the grasses Dactyloctenium radulans and Yakirra australiense, bulbs, larvae, termites, ants, spiders, fruit, fungi, lizards and occasionally eggs, snails, or small mammals. The proportion of insect to plant material in their diet depends on the habitat and season.

In addition to their keen sense of smell, greater bilbies put their excellent hearing to work when hunting. Placing their enormous ears against the ground, greater bilbies are able to hear termites and other insects burrowing underground. They then use their sharp claws and strong forelimbs to dig up them. The same digging skills are put to use to obtain bulbs, roots and other buried food. Greater bilbies have soft fur that does not protect their bodies well from termite and ant bites. They dig tunnels leading to termite chambers and lap them up with their long, slender tongues. Unfortunately, when they do this they also consume large amounts of soil and sand. Controlled fires benefit greater bilbies because fire promotes growth and seed production of preferred food plants.

Greater Bilby Behavior and Communication

Greater bilbies are fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), saltatorial (adapted for leaping), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), solitary and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). Their home territories range from 18 to 316 hectares (44.5 to 780 acres). Home range sizes of male greater bilbies are usually much larger than those of females. Female home ranges range from 18 to 150 hectares (44.5 to 371 acres) while those males range from 150 to 316 hectares (371 to 780 acres). [Source: Emily Brown, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Greater bilbies tend to live solitary lives, though some may live together in pairs (usually two females). They are the only members of the bandicoot-bilby family to construct their own burrows. They dig slightly spiraling burrows about two meters (5.5 feet) deep and up to three meters (10 feet) in length. These burrows may have multiple exits, which help thwart invasions by predators. A single bilby may have several burrows scattered through its home range. These burrows serve as protection from predators, heat and harsh environmental conditions and as a safe place for females to hide young while foraging. Greater bilbies tend to spend the day in their and emerge at night to forage and sometimes search for mating opportunities. They may periodically return to their burrow throughout the night to rest or escape a predator. Home ranges of males, females, and juveniles likely to overlap, but not much social contact occurs except during the mating season. Male greater bilbies in captivity possess a linear social hierarchy. While bilbies are somewhat less aggressive than bandicoots, they do defend their territory when necessary. Unlike bandicoots, the bilby social hierarchy is not maintained by high levels of aggression. Scent markings outside of burrows seem to signal where an animal is in the dominance hierarchy.

Greater bilbies sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. They have poor eyesight and mainly rely on hearing and olfaction for perceiving their environment. They have a keen sense of smell, which is used to sniff out food buried underground as well as perceive scent markings of other individuals. With their enormous ears, greater bilbies also listen for insects underground as well as predators (See Diet Above). However, hearing seems much less important than olfaction.

Greater bilbies communicate with chemicals and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. . Males mark the outside of their burrows by rubbing their urogenital area along the burrow entrance. They may also mark burrows where they have mated with a female. Scent marking appear to expressions of male dominance; dominant males mark over areas of less dominant males. Also, less dominant males tend to avoid entering burrows of dominant males. Females rarely scent mark their territories. Scent marks by males have little effect on the females since males are rarely, if ever, aggressive towards females. |=|

Greater Bilby Mating and Reproduction

Greater bilbies are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in year-round breeding. They can have up to four litters a year. The average gestation period is 14 days. The number of offspring ranges from one to 4, with the average number of offspring being 1-2, with the average number of offspring being two. [Source:Emily Brown, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Among greater bilbies the most dominant male typically mates with the most dominate female and additional females while lower males will mate with females equal or below them in the social hierarchy. Much of what is known about the reproductive habits of greater bilbies is based on the study of captive bilbies. Little of such behavior has been observed in wild bilbies. Emily Brown wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Males initiate sexual interactions by approaching and following a female. This is followed by the male sniffing the female around her face, shoulders, flanks, or under the tail as well as licking the female’s urogenital opening. Females may also sniff the male. Females may aggressively rebuff the advances of lower-ranked males. Copulation seems to take place underground with the longest mating sessions recorded taking place for around 18 hours. There is no evidence of pair bonding, though males will often scent mark the burrow after mating with a female. This is thought to ward off lower-ranked males. |=|

When breeding occurs depends on environmental conditions. In their arid environments, females may delay mating until conditions are appropriate to support the nutritional demands of lactation and independence of the young. When environmental conditions are favorable, a female bilby may produce up to four litters a year. Female greater bilbies reach sexual maturity at around five months old and males do so at eight months. The female estrus cycle lasts around 21 days.

Greater Bilby Mating Offspring and Parenting

Among greater bilbies parental care is provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. After birth, young greater bilbies climb into their mother’s pouch, attaches itself to a nipple where they remain until weaning which occurs after 75 days, with independence occurring on average at 14 days later. After that, the young will leave their mother's burrow and be left to fend for themselves.

During the period that young bilbies are in the pouch, they continue to grow at a very fast rate, reaching 200 grams by the time they leave the pouch. While in the pouch, they obtain all of their nourishment from mother’s milk. Bilby females have nipples both deep inside the pouch and nipples that hang outside the pouch. Each type of nipple provides a different type of milk for the offspring living outside the pouch versus inside the pouch.

Once the young emerge from their mothers pouch, they do not return. Many times, the female has already mated and a new neonate enters the pouch soon after the previous litter has left. These young juveniles are cached by the mother in one of her burrows where she returns regularly over the next two weeks to allow her babies to suckle. After these two weeks, the young leave the burrow and must fend for themselves with no additional parental care. It is estimated that only 25 percent of offspring produced will reach adulthood while the rest will become prey for predators or succumb to the elements.

Benefits of Bilbies

Greater bilbies have been called “ecosystem engineers” — “organisms that modify, maintain, create or destroy structure within the physical environment”. They dig 25-centimeter (10-inch) -deep pits when they forage for bulbs, seeds, and insects. These pits become areas where seeds, water, and other organic matter collect, decompose and turn into “fertile patches” in the Australian desert in which other seeds germinate and have enough fertilization to grow. Studies comparing environments with greater bilbies and a similar digging animals such as bettongs and those without such animals found that environments without the native digging animals suffered from losses of native Australian fauna despite the presence of rabbits, which also dig burrows. [Source: Emily Brown, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Greater bilbies also play an important in arid Australian outback ecosystem by digging burrows that provide habitat for dozens of species. Annie Roth wrote in National Geographic: Bilbies live in notoriously inhospitable regions of Australian outback, where temperatures can reach 104 degrees Fahrenheit and wildfires are a regular occurrence. Bilbies shelter themselves from these environmental extremes by spending most of their time in burrows nearly seven feet deep. By building these holes in what would otherwise be a largely flat and featureless landscape, bilbies transform the outback into an oasis for wildlife, says Stuart Dawson, a zoologist and research associate at Murdoch University in Western Australia and lead author of new research on bilbies. [Source: Annie Roth, National Geographic, April 18, 2019]

In 2014, Dawson set up motion camera traps outside 127 bilby burrows in the northern region of Western Australia to determine how many species take advantage of these subterranean shelters. Over the next two years, his cameras photographed hundreds of birds, reptiles, and mammals entering and foraging outside of bilby burrows. Dawson suspects that the animals observed inside the burrows were using them to escape predators and stay cool.

“This study really highlights the fact that if you lose the micro-habitats that bilbies provide, other species in the ecosystem become more susceptible to predators, temperature extremes, and other forces,” says Brendan Wintle, professor of conservation ecology at the University of Melbourne, who wasn’t involved in the study. Despite their small size, bilbies are capable of digging several burrows a day, which also aerates the soil and makes their ecosystem more hospitable to plant life, Wintle adds.

Greater Bilbies, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, greater bilbies are listed as Vulnerable; On the U.S. Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. Greater bilbies are promoted as a mascot for the Commonwealth of Australia Endangered Species Program. [Source: Emily Brown, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

In the past greater bilbies were hunted for food and fur for Aboriginal peoples. Their rarity and protected status of greater bilbies has meant that such practiced have ended. Bilby populations are believed to have declined drastically as a result predation by introduced foxes and cats and competition with introduced rabbits for forage and burrows. In addition to predation by introduced species, these invasive animals have also introduced new diseases and parasites that greater bilbies are highly susceptible to. The bilbies have been infected when they come into contact with feces of introduced species while digging. Without immunities to fight these parasites and diseases, many have died. The introduction of both European rabbits and livestock has greatly reduced the abundance of grasses, seeds, and other plant matter typically fed upon by native greater bilbies. Greater bilby habitat has also been destroyed and degraded as a result of human development and some have been hit by cars on roads.

Greater bilbies are protected under Australian law. A number of breeding and reintroduction projects are underway, as well as projects to control populations of harmful invasive species. The conservation status in each of the Australian territories is as follows: Queensland — extinct, Northern Territory — threatened, Western Australia — vulnerable, South Australia — Endangered, New South Wales — presumed extinct.

Their main known predators of greater bilbies are red foxes, domestic cats, dingoes, carpet pythons, monitor lizards and raptors. Red foxes were brought to Australia for the purpose of recreational hunting in 1855 by European settlers. Within 100 years of their introduction, red foxes spread across continental Australia and currently inhabits all regions of the continent with the exception of the tropical northern region of Australia. Domestic cats were originally released throughout Australia around 1855 to control the population of another invasive species, European rabbits, as well as mice and rat populations. Domestic cats quickly expanded over the entire continent of Australia, killing many native species.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025