Home | Category: Animals / Marsupials

SUGAR GLIDERS

Sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps) are relatively small gliding possums. Their common name refers to their fondness sugary foods, particularly sap and nectar, and their ability to glide through the air like flying squirrels. They have very similar habits and appearances to flying squirrels even though they are not closely related at all — and are thus good examples of convergent evolution. Their scientific name, Petaurus breviceps, means "short-headed rope-dancer" in Latin, a nod their acrobatics in the canopy of the forest.

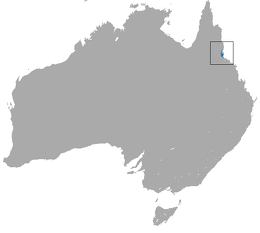

The range of sugar gliders has traditionally been placed in northern and eastern Australia, New Guinea and certain nearby islands and the Bismark Archipelago but this has changed (See Below). Now the sugar glider range is limited to the coastal forests of southeastern Queensland and most of New South Wales. Sugar gliders can live in forests of different types as along as there is an adequate food supply. They build their nests in the branches of eucalyptus trees inside their territory. The range of sugar gliders overlaps somewhat with the ranges of Krefft's gliders, squirrel gliders and yellow-bellied gliders, all of which coexist through niche partitioning where each species has different patterns of resource use. [Source: Jason Pasatta, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Sugar gliders have an average weight of 110 grams (3.88 ounces). Their head and body are approximately 12 to 32 centimeters (4.7 to 12.6 inches) long and their tail is 15 to 48 centimeters (5.9 to 18.9 inches) long. Sugar gliders are generally blue-grey on their, with somewhat paler undersides. A dark stripe runs down their back, beginning at their nose. Similar stripes are located on each side of the face running from the eye to the ear. The gliding membranes of sugar gliders extends from the outer side of the fore foot to the ankle of the rear foot and may be opened by spreading out the limbs. Females have a well developed pouch. Their average basal metabolic rate is 0.517 watts. Their average lifespan in captivity is 14.0 years.

Sugar gliders are quite common in Australia. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are classified as a species of “Least Concern” but being range-restricted they are sensitive to ecological disasters, such as the 2019-20 Australian bushfires, which significantly affected large portions of their habitat. In the last couple of decades sugar gliders have become popular pets. Its out out most of them are probably Kleppt’s gliders. In the U.S., the guidelines and rules for owning and breeding sugar gliders varies from state to state.

RELATED ARTICLES:

GLIDERS OF AUSTRALIA AND NEW GUINEA: MARSUPIAL EQUIVALENTS OF FLYING SQUIRRELS ioa.factsanddetails.com

POSSUMS OF AUSTRALIA AND NEW GUINEA: SPECIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BRUSHTAILED POSSUMS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SPECIES, PESTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSCUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSCUSES OF SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

Sugar Glider Behavior, Diet and Reproduction

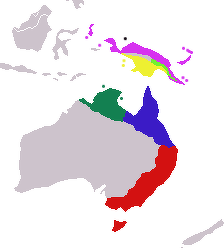

formerly recognized subspecies of sugar glider: A) P. b. breviceps (introduced in Tasmania) (red); B) P. b. longicaudatus (blue); C) P. b. ariel (now recognized as the species Savanna glider (Petaurus ariel) (olive green); D) P. b. flavidus (yellowish green); E) P. b. tafa (green); F) P. b. papuanus (purple); G) P. b. biacensis (now recognized as Biak glider (Petaurus biacensis)(black)

Sugar gliders are nocturnal (active at night), arboreal (live mainly in trees), territorial (defend an area within the home range), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Utilizing a membrane stretching between fore- and hindlimbs to glide, they are extremely active animals and can glide up to 45 meters. Sugar gliders are omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). They are especially found of the sweet sap which can be found in the eucalyptus tree. Their diet also includes pollen, nectar, insects and their larvae, arachnids, and small vertebrates. During the spring and summer sugar gliders predominately feed upon insects, mainly moths and beetles, and during the fall and winter months they feed on plant products, such as eucalyptus sap and pollen.

Sugar gliders live in parts of southern Australia where it can get cold in winter, and have developed strategies to deal with this. Groups huddle together to avoid heat loss, and individuals enter daily torpor for two to 23 hours to conserve energy while resting. Torpor differs from hibernation in that torpor is usually a short-term daily cycle. Entering torpor saves energy for the animal by allowing its body temperature to fall to a minimum of 10.4 °C (50.7 °F) to 19.6 °C (67.3 °F). When food is scarce, as in winter, heat production is lowered in order to reduce energy expenditure. With low energy and heat production, it is important for the sugar glider to put in weight and increase their body fat in the autumn (May-June) in order to survive the following cold season. When its hot, sugar gliders can tolerate air temperatures up to 40 °C (104 °F) through behavioural strategies such as licking their coat and exposing the wet area, as well as drinking small quantities of water.

Sugar gliders nest in groups of up to seven adult males and females and their young, all of whom are related. Jason Pasatta wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Groups of sugar gliders are mutually exclusive and territorial. Each group defends a certain number of eucalyptus trees which provide the group with its staple food source. The adult males of the group regularly mark this territory with their saliva and with the secretions of their anal, hand, and foot scent glands. Sugar gliders also have scent glands located on the forehead and chest that are used by the males in a group to mark all of the other members. There is usually one dominant male in each group of sugar gliders, who is responsible for most of the marking of the territory and the group. This male is usually heavier, produces more testosterone, and mates more frequently with the females of the group. When another animal is detected that it does not belong to the group because it does not have the group scent, it is immediately and violently attacked. Within groups, no fighting takes place beyond threatening behavior. Sugar gliders can also communicate through the variety of sounds they can produce, such as an alarm call which sounds like the barking of a small dog. The territory size of a group of sugar gliders are around 2.5 acres. [Source:Jason Pasatta, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Sexual maturity in sugar glider females occurs around eight months; for males it is around late 15 months. Females have an estrus cycle of approximately 29 days. In southeastern Australia young are born from June to November. Gestation usually lasts around 16 days. Sugar gliders usually giver birth to one or tow young, each of which weigh about 0.19 grams at birth. Young first leave the pouch after 70 days, and after about 111 days, they leave the nest and become independent shortly thereafter. Females are not pregnant while young are still dependent on them. Sometimes females may become hostile towards their young so that they leave sooner and female may become pregnant again.

Biak Gliders, Krefft's Gliders and Savanna Gliders

Studies have found significant genetic variation within populations traditionally classified in sugar gliders and this has resulted in sugar gliders being divided into four species. The subspecies P. b. biacensis, from Biak Island off of New Guinea, was reclassified as a separate species, the Biak glider (Petaurus biacensis). Wall Street Journal Wikipedia]

In 2020, a landmark study suggested that sugar gliders actually comprised three cryptic species (animals difficult or impossible to distinguish based on outward appearance (morphology) but are genetically distinct and reproductively isolated): 1) Krefft's gliders (Petaurus notatus), found throughout most of eastern Australia and introduced to Tasmania; 2) savanna gliders (Petaurus ariel), native to northern Australia; and 3) more narrowly defined sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps), restricted to a small section of coastal forest in southern Queensland and most of New South Wales.

On top of this, other sugar glider populations throughout this range (such as those on New Guinea and the Cape York Peninsula) may represent undescribed species or be conspecific with previously described species. This indicates that contrary to previous findings of a large range (which in fact applied to Krefft’s gliders and, to a lesser extent, to svanna gliders.

Sugar gliders and Krefft’s gliders are estimated to have diverged about 1 million years ago, and may have originated from long term geographic isolation. The early-mid Pleistocene saw an uplifting of the Great Dividing Range, contributing to and coinciding with aridification of the interior of Australia, including on the western side of the range. This, as well as other climactic and geographic factors, may have isolated the ancestors of sugar gliders breviceps to the eastern, coastal side of the Great Dividing Range — an example of allopatric speciation.

Squirrel Gliders

Squirrel gliders (Petaurus norfolcensis) are nocturnal gliding possums. One of the wrist-winged gliders of the genus Petaurus, they are found in eastern Australia throughout eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria, and southeast South Australia. They favor dry sclerophyll (hard leaf) forest and woodlands, but are not found in dense coastal ranges. In northern New South Wales and Queensland they inhabit coastal forest and some wet forest areas that border rainforest.

Squirrel gliders range in weight from 190 to 300 grams (6.70 to 10.57 ounces) Squirrel gliders have pale grey fur on their back side, with a dark brown or black stripe down the middle. They possess a prehensile tail, an opposable big toe and a long gliding membrane that extends from the outside of the forefoot to the ankle. |Squirrel gliders have long, sharp, diprotodont lower incisors. Their molars are bunodont, and they possess a total of 40 teeth. Their average lifespan in captivity is 11.9 years.[Source: Barbara Lundrigan and Melinda Girvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Squirrel gliders are similar to sugar gliders in appearance, but are twice as large and have more distinct facial markings, a longer face, and a bushier tail than sugar gliders. At times though, these two species can only be reliably distinguished by the larger molar teeth of squirrel gliders

Squirrel gliders are not endangered or threatened. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are classified as a species of “Least Concern”. In some habitats, density of Squirrel gliders are as high as three individuals per hectare. But in the southern part of their range their numbers have delcines as result of the mass clearing of woodland for agriculture and forestry. The animals rely on trees for food and nesting sites. |=|

Squirrel Glider Behavior, Diet and Reproduction

Squirrel gliders are nocturnal (active at night), arboreal (live mainly in trees), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They utilize the membrane stretching between their fore- and hindlimbs to move from tree to tree. They nest in tree hollows where they construct a bowl-shaped nest lined with leaves. They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. |Males have well-developed scent glands on their foreheads which they use to mark their territory. Squirrel gliders engage in some vocal communications. They produce gurgling chatters; soft, nasal grunts; and repetitive, short gurgles. [Source: Barbara Lundrigan and Melinda Girvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Typical squirrel glider family groups consist of a mature male of over two years of age, one or more adult females, and the young of that season. In captive situations, established family groups have been reported to attack newly introduced individuals and antagonistic behavior has been displayed between communitites of Squirrel gliders

Squirrel gliders are an omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). Typical foods include insects (mainly beetles and caterpillars), acacia gum, sap from certain eucalypts, nectar, pollen, and the green seeds of the Golden Wattle. Nectar and pollen are the most important dietary items, but in the absence of these foods the squirrel glider will more heavily utilize sap and gum. |=|

The breeding season of squirrel gliders is in June and July. The average gestation period is 20 days. Females have a well-developed pouch from June to December that opens towards the head and has four nipples. From January through May, the female's pouch is small and dry, indicating anestrus. Male Squirrel gliders produce sperm throughout the year. Females give birth to one or two young. These young stay in the mother's pouch for approximately 70 days after birth. The young are fully furred at approximately 76 days and open their eyes at 84 to 85 days. Young remain in their mother’s nest for another 40-50 days after emerging from the pouch. At the age of 110-120 days, young gliders begin to venture out and forage with their mother. |=|

Mahogany Gliders

Mahogany gliders (Petaurus gracilis) are an endangered gliding possum that live in a small region of coastal Queensland in Australia between Toomulla and Tully and about 40 kilometers inland. They live in highly fragmented open Eucalyptus woodlands as well as swampy coastal lowlands at elevations between 20 to 120 meters (65.6 to 393.7 feet). They were described in 1883 when they were thought to be a subspecies of more common squirrel gliders. Then they weren’t seen for over 100 years. They were "rediscovered" in 1989 and attained the status of species in 1993. [Source: Breah Goff, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mahogany gliders are the second largest species of glider in Australia. They range in weight from 310 to 500 grams (10.9 to 17.6 ounces) and have an average length of 60 centimeters (23.62 inches), including their tail. They are grey and brown in color with a long black stripe along the back of their coat. Their underbelly is creamy mahogany in color — the source of their common name. Mahogany gliders have a thin fold of skin between their front and rear legs that stretches out like a parachute when they leap, allowing them to glide distances of 30 to 60 meters. Their long tail is used to stabilize them as they glide. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Adult males weigh from 337 to 500 grams (11.9 to 17.6 ounces) while females weigh from 310 to 450 grams (10.9 to 15.7 ounces).It is believed that the lifespan of mahogany gliders are similar to that of the sugar glider of Australia, which is aproximately six years in the wild

Mahogany gliders are primarily herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) but also recognized as , folivores (eat leaves) and nectarivores (eat nectar from flowers),. Animal foods include insects. Among the plant foods they eat are fruit, nectar. pollen. flowers. And sap or other plant fluids They primarily feed on nectar and pollen from a variety of trees and shrubs within their home-range, including many species from the family Myrtaceae such as Corymbia (Corymbia intermedia), Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus cloeziana) and Melaleuca (Melaleuca dealbata). At higher elevations, Bankasia trees such as Bankasia aquilonia and Bankasia plagiocarpa are also likely sources of food. When little else is flowering, mahogany gliders also consume Acacia trees, including Acacia crassicarpa, A. flavescars and A. mangium. Most plants in the diet of mahogany gliders are available during certain times of the year. Timing and availability of food affects time and energy invested in foraging, including the distance traveled to obtain food. During times of a high flowering index, mahogany gliders tend to travel further and maintain a larger home-range. During times of a low flowering index, they appear to maintain a smaller home range.

Mahogany gliders are listed as Endangered on the Red List of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Australian Endangered Species Protection Act of 1992. Less than 20 percent of their habitat remains because of clearing for agriculture, intensive grazing, weed invasion, forestry, and human settlement. Their arboreal habitats keeps them out of range of foxes and cats. Among the natural predators that prey on them are Amethystine pythons, Rufus owls, Barking owls, Masked owls, Sooty owls, and Carpet pythons. Their population is currently estimated to be 1,500 individuals and is declining. Because mahogany gliders require near continuos vegetation, roads, power lines, and railway lines prevent movement to potential habitats. A recovery plan was created in 1999 to help them. It recommended establishing protected reserves, altering barbed wire fences which have injured and killed gliders and setting up artificial den boxes which can be used by mahogany gliders for nests.

Mahogany Glider Behavior and Reproduction

Mahogany gliders are arboreal (live mainly in trees), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and territorial (defend an area within the home range). The average territory size for females is 10 hectares (24.7 acres); for males, 20 hectares (49.4 acres). Mahogany gliders are very defensive of their territory, viciously attacking other mahogany gliders that intrude on it. Individuals of both sexes travel the border of their territory in a "foraging loop" every two to three nights either early in the evening before feeding or after feeding prior to returning to their den. This loop appears to have two purposes: to maintain defensive borders as well as to locate trees that may be fruiting or flowering in the near future. Well developed scent glands on the front of their heads as well as on the front of the chest of males help to maintain the home range of mahogany gliders. Scent marking is also performed by urinating on the branches of trees. [Source: Breah Goff, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mahogany gliders are generally solitary although they do appear to be socially monogamous. Males and females do not forage with one another, and they generally sleep in dens in hollows of trees alone but sometimes do so with a member of the opposite sex. Mahogany gliders use 10 or more dens per season. Dens are usually made in hollows in Eucalyptus and bloodwood trees and are lined with a thick mat of leaves. Mahogany gliders can glide distances of 30 to 60 meters.

Mahogany gliders communicate with sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. They are very quite animals, rarely vocalizes more than once a night, when they emit a nasal sounding "na-when" call. This vocalization lasts no more than 10 minutes, and responses from either sex are rare. Vocal communication appears to be aimed at members of the opposite sex. . Even when defending their territory, mahogany gliders make few sounds. Most communication is carried out through scent marking. Mahogany gliders have scent glands in the front part of their head, and in males on the front of their chest, which they rub on trees in their territory. They also urinate on tree branches to mark territory. |=|

Mahogany gliders are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and engage in seasonal breeding. Mahogany gliders generally breed only once a year and the breeding season is between April and October. The number of offspring ranges from one to two, with the average number being 1.55. Occasionally, females breed twice in one season when the first litter is born early enough in the season to permit a second attempt at breeding. They may also breed twice in a season if the first litter of offspring dies.

Parental care is provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Females carry their young in their pouch until they are weaned at four to five months of age. They have been observed raising young in up to 12 different nests per season. Once weaned, juveniles disperse from the nest to survive on their own; this generally occurs within their first year. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 12 to 18 months. It has been suggested that the breeding rate of females does not fully peak until their second year when they reach full adult size and weight. Although mahogany gliders appear to be monogamous, males don’t appear to be involved in parenting.

Yellow-Bellied Gliders

Yellow-bellied gliders (Petaurus australis) are also known as fluffy gliders. They are an arboreal and nocturnal gliding possums that live in native eucalypt forests along the eastern and southeastern coasts of Australia in Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria. They can found in inland up to several hundred kilometers and have an extensive, but fragmented patchy distribution. They are is generally found in low densities and its rare to see them throughout most of their range, although it can be locally common such as in east Gippsland in Victoria.[Source: Ross Secord, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Yellow-bellied gliders favor coastal and open foothill forests and woodlands, and wet eucalypt forests. In eastern Australia they live only in tall, mature eucalypt forests in regions of high rainfall, with temperate to subtropical climates. The northern Queensland they tend to live in forests at high altitudes with lower temperatures. They occurs in the highest densities in coastal and foothill forests and woodlands, and in lower densities in wet eucalypt forests. Winter flowering eucalypts (e.g. Eucalyptus maculata) may be important in habitat preference in southern Queensland. Higher numbers seen in New South Wales may correlate to a continuous supply of nectar due to a greater diversity of eucalypts.

Yellow-bellied gliders Are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Since yellow-bellied gliders is strongly tied to certain species of eucalypt trees, removal or damage to these trees hurts them and reduces their habitat. Eucalypt forests in Australia are cut for timber or cleared for agriculture. The removal of old growth elements from unlogged forests or from previously lightly-logged forests results in a decline in density of these animals. Because the species requires a variety of trees to feed on in mixed forest over large home ranges, and because it needs hollow trees for nesting, its conservation requires the preservation of large tracts of forests. There is also evidence that expansion of rainforest into the wet sclerophyll (hard leaf) forests preferred by yellow-bellied gliders has diminished their range. Rainforest expansion is believed to be due to a reduction in the intensity of fires along the western margins of rainforests, possibly caused by controlled burning of undergrowth by cattle ranchers.

Yellow-Bellied Glider Characteristics, Diet, Behavior, Reproduction

Yellow-bellied gliders range in weight from 435 to 710 grams (15.33 to 25.02 ounces) and have a body and head length of 27 to 30 centimeters (10.6 to 11.8 inches) and tail length ranges from 42 to 48 centimeters (16.5 to 18.9 inches). The pouch of females has two incompletely divided compartments divided by a well developed septum, a feature unique among marsupials. The tail is prehensile and fully covered in fur. The fur of yellow-bellied gliders is fine and silky. Their back dusky grayish-brown in color and their undersides are creamy to yellowish-orange — the source of their common name. They have black feet, an oblique dark strip on their thigh, semi-naked ears and a pink nose. A gliding membrane is connected from their wrists to their ankles. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Their average lifespan in captivity is 10.0 years. [Source: Ross Secord, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Yellow-bellied gliders are extremely active, arboreal (live mainly in trees), nocturnal (active at night), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and motile (move around as opposed to being stationary). Researchers have recorded glide distances up to 114 meters. Yellow-bellied gliders are the most vocal of the gliders, and often lets out a loud call when they glide. They usually carry their a vertically erect manner, similar to felids. As they are territorial they can be very aggressive towards trespassers in their home range. They are social to some extent: many live in small family groups comprised of one adult male and one or two females with their offspring. They typically reside in a leaf-lined nest in a hollow tree and sleep there during the day.

Yellow-bellied gliders are primarily herbivores (eat plants or plants parts), folivores (eat leaves), (eat leaves) but are also recognized as omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). Their diet consists mainly of nectar, pollen, and the sap of eucalypts. Sap is obtained by incising the bark on the upper branches and trunks of Eucalyptus resinifera trees with their claws and drinking the ooze. Some individual trees are clearly favored and become very heavily scarred. They also eat insects, arachnids, grubs, and possibly small vertebrates.

On average male and female yellow-bellied gliders reach sexual or reproductive maturity at two years of age and the number of offspring is usually one, occasionally two. Breeding is limited to August through December in Victoria but occurs throughout the year in Queensland. Mating is done while clinging to the underside of a branch. Females have two nipples in the incompletely divided pouch. Young are carried in the mother's pouch for about 100 days, after which time they are left in a nest for an additional 60 days. Both parents provide care for the young, which become independent after 18 to 24 months.

Greater Gliders

It was long thought that greater gliders were a single species comprised of three subspecies but in recent years these subspecies have been elevated to species status. They are: 1) Greater gliders (Petauroides volans); 2) Central Greater gliders (Petauroides armillatus); and 3) Northern Greater gliders (Petauroides minor). The distinction first widely appeared in print in 2012 and 2015 in field guides written by Colin Groves and Stephen Jackson and was confirmed by a 2020 analysis which found significant genetic and morphological differences between the three species, which have subsequently been recognized by the American Society of Mammalogists. The Australian Government's Species Profile and Threats Database (SPRAT) recognize two species: ) Central and Greater glider (Petauroides volans) and Northern greater glider (Petauroides minor). [Source: Wikipedia]

The three greater glider species mainly differ in where they live and in their size, with the northern greater glider only growing to the size of a small ringtail possum, while the Greater glider grows to the size of a house cat. The central greater glider is intermediate between these two. Greater gliders are found from southern Victoria northwards into New South Wales and perhaps Queensland (its precise northern boundary is still debated). Northern greater gliders are found in the northern part of the greater glider's range but southern boundary of its range has been clearly established. Central greater gliders occupy the range between the northern and southern species, extending north from Victoria, but its northern extent is also not fully defined.

Greater gliders are not closely related to the Petaurus group of gliding marsupials (including sugar, mahogany, squirrel and yellow-bellied ones described above). Greater gliders are more closely related to Lemuroid ringtail possums (Hemibelideus lemuroides), which are both in the subfamily Hemibelideinae. Hybridization between the different greater glider species occurs. Greater gliders live in eastern Australia in tall eucalyptus forests — and never rainforests — in eastern Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria. Greater gliders are associated with high basal areas of over-story, and they need large patch sizes of old-growth forest. They are most often found in sites containing many trees with hollows. A single glider may use 4-18 den sites Patches of old growth must be at least 20 hectares to sustain a population of these animals.

Greater gliders are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Although widespread and abundant in some areas, they are scarce in other areas. Great gliders were never hunted so much. Although their fur is long and thick, it is rather loose and soft which makes it difficult to work with. Fur traders rarely wanted their skins. But since greater gliders require large patches of old growth habitat their needs can conflict with those of humans who want to cut the trees for timber or .

Greater gliders are very sensitive to clear-cuts and fragmentation of their old-growth eucalyptus habitat. One study found that over 90 percent of gliders displaced by a clear-cut die rather than establish a new territory in suitable habitat nearby. This may due to 1) greater gliders are specialist feeders, and only eat the leaves of some eucalyptus trees; 2) they only carry limited quantities of body fat, and are likely to undergo rapid changes in body condition under adverse conditions; and 3) they are very awkward on the ground, and so have difficulty in crossing open tree-less areas.

Greater Glider Characteristics and Diet

Southern greater gliders are the largest of the gliding possums. About the size of a cat, they range in weight from one to 1.5 kilograms (2.2 to 3.3 pounds) and have a head and body length of 30 to 48 centimeters 11.8 to 18.9 inches). Their is 45 to 55 centimeters (17.7 to 21.7 inches) long. Their average basal metabolic rate is 3.191 watts. Northern greater gliders are smaller and central greater gliders are between the two.

Greater gliders have a short snout and large round ears covered by thick fur. The patagium (gliding membrane), which is also covered with fur, extends from the knee to the elbow. This different than sugar gliders and other Petauridae, whose patagium extends from the ankle to the wrist). Greater gliders have a triangular shape when in the air . The long, furred tail, which is not prehensile, is used as a rudder. Females have a well-developed pouch and two mammae. Color varies more among greater gliders than that of any other marsupial. The very long, dense fur is typically brownish-black, but can range from pure black with a creamy underside, to dusky browns and grays, cinnamon, red, yellow, and completely white. [Source: Juliet Nagel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Greater gliders are folivores (eat leaves), subsisting almost entirely on eucalyptus leaves that they break down with bacterial fermentation in an enlarged cecum. Their specialized diet means they are very difficult to keep in zoos. Greater gliders rarely need to drink. Their average lifespan in wild is six years. They can live up to 15 years.

Greater Glider Behavior and Reproduction

Greater gliders are solitary, nocturnal (active at night), arboreal (live mainly in trees), territorial(defend an area within the home range), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and sedentary (remain in the same area). They have with a home range of one to 2.2 hectares (2.5 to 5.4 acres). Home ranges of females overlap. Males keep separate territories. Greater glider nest in tree hollows high up in both living and dead trees. The hollows are occasionally lined with strips of bark or layers of leaves. They sometimes transport nesting material rolled-up in their tails.

Greater gliders are awkward and slow on the ground, but they are agile in trees and in the air. When they glide, they bend their forearms, with the hands almost meeting in front of the chest. They use their long, furred tail as a rudder. Greater gliders may use their patagium as a blanket to reduce heat loss by wrapping it around themselves like a bat. On hot days, they lick their fur to lose heat through evaporation. Owls may represent the largest threat to gliders. Powerful owls and sooty owls both prey upon them. Dingoes and introduced foxes also take them. Because they are gliders, it is likely that they can escape predators by gliding away.

Greater gliders are are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). The breeding season begins in March, and young are born between April and June. Males and females will normally share a den from the onset of breeding until the young emerge from the pouch. The number of offspring is one. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age two.

Parental care by greater gliders is carried provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Development must be completed in the mother's pouch. While some males are monogamous and others are polygynous, they are generally not involved in the care of young. Offspring are ensconced in the mother’s pouch until September, suckling on one of her teats then, when the weigh about 300 grams, ride on the their mother’s back until November or December. In January, when they weigh about 600 grams, they become independence. Until weaning, approximately half of the offspring produced are male. After the weaning period, the proportion of the population that is male drops to 39 percent.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025