Home | Category: Animals / Animals / Marsupials

BANDICOOTS

Bandicoot Species: 3) Northern Brown Bandicoot (/soodon macrourus); 4) Western Barred Bandicoot (Perameles bougainville); 5) Eastern Barred Bandicoot (Perameles gunnii); 6) Long-nosed Bandicoot (Perameles nasuta), 7) Giant Bandicoot (Peroryctes broadbenti); 8) Raffray’s Bandicoot (Peroryctes raffrayana)

Bandicoots are small to medium-size shrew-like marsupials. They have strong hind legs well adapted for jumping and use their long nose and sharp claws on the forelimbs to probe sand and soil for roots and insects on which they eat. The term “bandicoot” is derived from the Indian-Telugu word for “pig rat”, which initially referred to a large rodent species, the greater bandicoot rat, from India and Sri Lanka., that is unrelated to bandicoots in Australia and New Guinea. |=|

Bandicoots average about 24 centimeters (9.5 inches) in length and weigh 172 to 296 grams (6 to 10.4 ounces). They have V-shaped faces, ending with a prominent noses that give them, and bilbies, an appearance family to elephant shrews of which bandicoots are distantly related. Like most marsupials, male bandicoots have bifurcated penises and females have pouches. his pouch is where their young, which are born in a very undeveloped state, develop further after birth. The pouch opening is unique, facing backwards to prevent dirt and debris from entering while the mother is digging for food

There are 20 species of bandicoot. They live mostly in hot places. They have large ears to dissipate heat. A dense network of tiny blood vessels run close to the surface of the skin in ears. Bandicoots also have low body temperatures and low basal metabolic rates which aides their survival in hot and dry climates. They also have low total water evaporative rate and effective panting mechanisms which further aid their survival in hotter temperatures.

Bandicoots are nocturnal. They feed mostly at night and can maneuver easily through thick underbrush. They mainly eat insects but sometimes feed on plant material. During the day they sleeps in shallow nests covered by plants and grass.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BANDICOOT SPECIES IN SOUTHERN AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BANDICOOT SPECIES IN NORTHERN, EASTERN AND WESTERN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

BILBIES: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

POSSUMS OF AUSTRALIA AND NEW GUINEA: SPECIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BRUSHTAILED POSSUMS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SPECIES, PESTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

GLIDERS OF AUSTRALIA AND NEW GUINEA: MARSUPIAL EQUIVALENTS OF FLYING SQUIRRELS ioa.factsanddetails.com

GLIDER SPECIES (SUGAR, MAHOGANY, GREATER, YELLOW-BELLIED): CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSCUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSCUSES OF SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

Peramelemorphia

Medium-size marsupials in Australia and New Guinea include bandicoots, bilbies and bettongs. Peramelemorphia (bandicoots and bilbies) is an order that comprises 21 divided into seven genera and two families: Peramelidae (bandicoots and echymiperas) and and Thylacomyidae (bilbies). There used to be 22 species eight genuses and three families until the species pig-footed bandicoot in the family Chaeropodidae became extinct in the early 20th century.[Source: Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bandicoots and bilbies have a rodent-like appearance with short legs, a stocky body, a short neck, and a long, pointy nose. They are largely nocturnal (active at night), and possess a well-developed sense of smell and eyes that are well adapted for night vision. Most bandicoots and bilbies have brownish-red or tan fur and are sometimes marked with stripes. Long, rabbit-like ears also characterize some species. They range in size from less than 100 grams to over five kilograms, though most are about the size of a rabbit or smaller.

Bandicoots and bilbies are omnivores (animals that eat a variety of things, including plants and animals) that eat mainly insects, but also consume a variety of vegetable material and some vertebrates as well. They occupy a wide range of habitats throughout Australia, New Guinea, Tasmania and the surrounding islands.

Bandicoot and bilby populations have been devastated by attacks from feral and domestic cats. Bandicoots and bilbies live, on average, one to two years in the wild. While only one in 10 offspring usually survive, once they reach maturity life expectancy ranges from 2.5 to three years. In captivity, mean longevity for bandicoots and bilbies is two to four years.

Bandicoot Species

There are are three bandicoots subfamilies: 1) Peramelinae, 2) Peroryctinae, and 3) Echymiperinae. Peramelinae includes genera like Isoodon (short-nosed bandicoots) and Perameles (long-nosed bandicoots). Peroryctinae contains Peroryctes, which are New Guinean long-nosed bandicoots. Finally, Echymiperinae includes Echymipera (New Guinean spiny bandicoots), Microperoryctes (New Guinean mouse bandicoots), and Rhynchomeles (Seram bandicoot).

Seram bandicoot (Genus Rhynchomeles): one species: Seram bandicoot (Rhynchomeles prattorum) is also known as the Seram Island long-nosed bandicoot and is endemic to the island of Seram in Indonesia, which is west of New Guinea. New Guinean Long-Nosed Bandicoots (Genus Peroryctes, Subfamily Peroryctinae): Two species

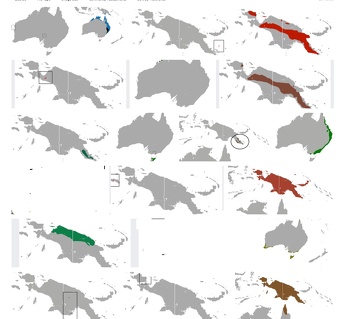

Range of different bandicoot species:

top row (left to right): 1) Western Barred Bandicoot (Perameles bougainville) (red — native, pink — reintroduced); 2) Northern Brown Bandicoot (Isoodon macrourus) (blue — extant, black — extinct); 3) David's Spiny Bandicoot (Echymipera davidi); 4) Mouse Bandicoot (Microperoryctes murina)

second row (left to right): 1) Raffray's Bandicoot (Peroryctes raffrayana); 2) Golden Bandicoot (Isoodon auratus); 3) Giant Bandicoot (Peroryctes broadbenti); 4) Eastern Barred Bandicoot (Perameles gunni) (green — native, pink — reintroduced)

third row (left to right): 1) Striped Bandicoot (Microperoryctes longicauda); 2) Papuan Bandicoot (Microperoryctes papuensis); 3) Long-nosed Bandicoot (Perameles nasuta)

fourth row (left to right): 1) Seram Bandicoot (Rhynchomeles prattorum); 2) Common Spiny Bandicoot (Echymipera kalubu)

fifth row (left to right): 1) Clara's Spiny Bandicoot (Echymipera clara); 2) Arfak Pygmy Bandicoot (Microperoryctes aplini)

bottom row (left to right): 1) Menzies' Spiny Bandicoot (Echymipera echinista); 2) Southern Brown Bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus); 3) Long-nosed Spiny Bandicoot (Echymipera rufescens)

Short-Nosed Bandicoots (Genus Isoodon): Three species:

Golden bandicoot (Isoodon auratus)

Northern brown bandicoot (Isoodon macrourus)

Southern brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus)

Southern brown bandicoot subspecies: Quenda or Western brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus fusciventer) and Cape York brown bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus peninsulae)

Long-Nosed Bandicoots (Genus Perameles): Three extant species:

Western barred bandicoot (Perameles bougainville)

Eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii)

Long-nosed bandicoot (Perameles nasuta)

Queensland barred bandicoot (Perameles pallescens)

The recently extinct species are:

†Desert bandicoot (Perameles eremiana)

†New South Wales barred bandicoot (Perameles fasciata)

†Southwestern barred bandicoot (Perameles myosuros)

†Southern barred bandicoot (Perameles notina)

†Nullarbor barred bandicoot (Perameles papillon)[5]

New Guinean Spiny Bandicoots (Genus Echymipera, Subfamily Echymiperinae): All Echymipera species are native to New Guinea. The common echymipera and long-nosed echymipera are also found on neighboring islands. Five species:

Clara's echymipera (Echymipera clara)

David's echymipera (Echymipera davidi)

Menzies' echymipera (Echymipera echinista)

Common echymipera (Echymipera kalubu)

Long-nosed echymipera (Echymipera rufescens)

New Guinean Mouse Bandicoots (Genus Microperoryctes): Five species:

Arfak pygmy bandicoot (Microperoryctes aplini)

Striped bandicoot (Microperoryctes longicauda)

Mouse bandicoot (Microperoryctes murina)

Eastern striped bandicoot (Microperoryctes ornata)

Papuan bandicoot (Microperoryctes papuensis)

Bandicoot Habitat and Range

Bandicoots are mainly found in Australia, New Guinea, and the surrounding islands. It is believed that they members of the subfamily Peroryctinae most likely originated and radiated in New Guinea. However, their origin is speculative due to a lack of fossil evidence. Only two out of the 11 species of peroryctine bandicoots, the rufous spiny bandicoot and the Seram bandicoot, are currently found outside of New Guinea having ranges that extend to the tip of Cape York and Seram Island, respectively. The northern brown bandicoot is the only perameline bandicoot that is found outside of Australia in Southern New Guinea. Eastern barred bandicoots and southern brown bandicoots are found in Tasmania. [Source:Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kathryn Frens wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Bandicoots occupy a wide range of habitats, with altitude and climatic differences heavily influencing the distribution of species. Members of the family Peramelidae inhabit a variety of ecosystems, ranging from deserts to subalpine grasslands to tropical lowland rainforests, while thylacomyids primarily live in arid areas. Eastern barred bandicoots and the now extinct pig-footed bandicoot prefer grassland habitats, golden bandicoots inhabit the Top End and Kimberly tropics of Australia, brown bandicoots live in more secluded forests and the only living species of bilby, the greater bilby, is a desert-dweller. By occupying a wide variety of habitats and vegetation types, bandicoots largely avoid competition.

In New Guinea, bandicoots (Peroryctinae) are distributed throughout a wide range of altitudes. However, several species may occur sympatrically at moderate altitudes. The northern brown bandicoot, giant bandicoot and most species of spiny bandicoots prefer lowland areas, though some may live as high as 2000 meters. Mouse bandicoots, striped bandicoots and Raffray’s bandicoots are upland species and typically live at elevations above 1000 meters. There is one known high altitude species, Seram bandicoots, that are only found at altitudes of around 1800 meters.

Bandicoot Characteristics

Bandicoots are terrestrial, ground-dwelling marsupials. Kathryn Frens wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Their bodies are compact in size with relatively short tails compared to the length of their bodies. Bandicoots have short necks, elongate skulls, and long, tapered snouts. Their ears are upright and can range from being small and rounded to fairly large and pointy. Males are usually larger than females and are socially dominant. [Source:Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The hind limbs of bandicoots are relatively long and exceptionally powerful. On the hind feet, the forth toe is the largest, while the bones of the second and third toes are fused, but still maintain separate claws (i.e., syndactyly). The front limbs are very short and well-adapted for ground foraging and digging. The first and fifth toes on the forefeet are either absent or lack claws if present. The second, third, and fourth toes have strong, flat claws for digging. They typically use their strong hind limbs to leap and hop through brushy habitats; however, when escaping danger they are able to run at a fast gallop. Their front and back legs work alternately. Characteristically, they land on hind and forefeet, and then take off with a push of their large hindfeet. |=|

Bandicoots can be most noticeably recognized by their unique marsupium, the pouch located on the venter used to carry immature young. Unlike teh marsupium of kangaroos and wallabies, the marsupium of bandicoots opens to the rear. Although this condition is present in some diprotodonts (such as wombats), it is probably uniquely derived in each lineage. |=|

Bandicoots are omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals) and their dentition is well-suited to a diet consisting of plants and insects. Unlike diprotodonts, which have only two lower incisors, bandicoots are polyprotodonts, having multiple lower incisors and anywhere from four to five upper incisors. Their incisors are flattened at the tips with the crown of the last lower incisor having two lobes. The canines are present and well-developed and they also have three premolars, which are narrow and pointed (plagialacoid) and four molars, which are tribosphenic or quadrate, in the upper and lower sets. This gives them the dental formula of 4-5/3, 1/1, 3/3, 4/4 = 46 or 48. |=|

Bandicoot Food, Eating Behavior and Predators

While adapted for insect-eating, most bandicoots are omnivores Bandicoots are omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). They consume a wide variety of invertebrates including termites, ants, earthworms, insect larvae, spiders and centipedes as well as plant matter such as grasses, bulbs and seeds. Some species feed on fungi, bird eggs and small vertebrates such as lizards and mice. [Source:Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bandicoots obtain food by digging or rooting through plant litter on the ground or in the ground itself. They forage by digging with their strong front claws and then using their long snout and tongue grab a hold of food items. Kathryn Frens wrote in Animal Diversity Web: While they can eat many different foods, each colony tends to show preference for one or two particular food types. This is most likely due to regional availability of each food type and helps reduce intraspecific competition for resources. Many bandicoot species acquire much of the water they need through their diet. Their front limbs are short and well-adapted for ground foraging and digging, and their dentition is ideally suited to a diet of plants and insects.

The main natural predators of bandicoots are owls, quolls, and dingoes. Bandicoots have relatively good defenses against these animals but this is less the case with introduced species such feral and domestic cats, dogs, foxes, which are considerable threats to many local populations. In the past, bandicoots could often be found in Australian suburbs, however, domestic animals have significantly reduced their population. To protect themselves from predators, bandicoots make nests in shallow holes in the ground, which they line with leaf litter. Leaf litter helps hide them from predators and protects them from inclement weather. A few species have calls, which can ranged from shrill alarm calls to low, huffing noises accompanied by barred teeth. |=|

Bandicoot Behavior

Bandicoots are fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and territorial (defend an area within the home range). All bandicoots are nocturnal (active at night) or crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), but the recently-extinct pig-footed bandicoot was diurnal (active mainly during the daytime). [Source: Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bandicoots are solitary, coming together only to breed. Kathryn Frens wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Both males and females select territories, although male territories are larger and generally overlap with those of several different females. Most bandicoots are hostile toward one another, defending their territory with fighting, chasing, and scratching. Males often warn each other with puffing sounds and may attempt to chase each other. Smaller males usually do not defend themselves against larger individuals when attacked. The only time bandicoots do not exhibit intraspecific aggression is when an estrus female encounters a male. Bandicoots are nocturnal (active at night).

While most bandicoots live in burrows that are constructed from piles of vegetation covering small ground depressions, some species are known to occupy tree hollows or abandoned rabbit burrows. Bilbies are the only members of the bandicoot-bilby family to construct their own burrows; however, some species of bandicoot are known to burrow into the sand to escape hot weather.

Bandicoot Senses and Communication

Bandicoots sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Like other nocturnal mammals, they depend greatly on their senses of touch, smell, and hearing while hunting. [Source: Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bandicoots communicate with vision, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also employ pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) and Many species possess a scent gland just in back of the ear, which is present in both genders in some species (such as northern brown bandicoot) and only present in males in others. These glands are used for marking territorial boundaries, and during male-male competition for mates or territory.

Males are extremely territorial, and during an encounter, they often mark the ground and surrounding plants with scents from their ear gland. Males warn potential rivals with by making puffing sounds and exhibit aggression with open-mouthed fighting and chasing. Captive bandicoots have been observed to make “soft spitting noises” when threatened. A few species have calls, which can ranged from shrill alarm calls to low, huffing noises accompanied by barred teeth.

Bandicoot Mating and Reproduction

Direct observations of bandicoot mating are rare but, based on certain behaviors, it has been deduced they are probably either polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) or polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. Although bandicoots are solitary, male territories overlap with those of several females. During the mating season males much of their time searching for receptive females in estrus. When they find one they follow her until she is ready to be mounted. Females may mate with more than one male. Also, they generally mate at about the time their previous litter leaves the pouch, so the weaning of one litter coincides with the birth of the next. [Source: Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bandicoots females have an estrus cycle, which is similar to the menstrual cycle of human females and polyestrus (females have multiple estrous cycles, periods of sexual receptivity, per year). Kathryn Frens wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Bandicoots are known for their accelerated breeding process, which enables a single female to give birth to as many as 16 young per year. Unlike all other marsupials, they have a chorioallantoic placenta, which replaces the more typical yolk sac placenta a few days into gestation. Unlike the placenta found in 'true mammals', the placenta of bandicoots lacks villi, resulting in relatively shorter gestation when compared to 'true mammals', which developed the chorioallantoic placenta independently.

Some bandicoots species engage seasonal breeding, typically in the spring, while others engage in year-round breeding. Day length, food availability, and weather conditions appear to have a significant impact on the timing of breeding in seasonal breeders. Year-round breeders occasionally show a decline in birthrate during times of food scarcity or drought. Gestation time is variable, from as little as 12.5 days in long-nosed bandicoots (among the shortest in any mammal) to about 14 days in several other species. Litters range in size from two to five offspring, but usually no more than four survive.

Bandicoot Mating Offspring and Parenting

Parental care by bandicoots is provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth, weighing about 0.2 grams at birth. Immediately after birth, young crawl into their mother’s pouch and attach to a nipple. They leave the pouch after about 60 days, and are weaned in about 70 days. [Source:Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Birth is very short, probably lasting less than 10 minutes, with the young weighing only about 0.5 grams. Another mating may occur about 50 days after birth, shortly after the weaning of the first litter. The new litter is born approximately 12 days later. In bandicoots, every offspring has its own teat, and receives the same amount of milk. Towards the end of the pouch period, the young are left in the nest, and approximately 8-10 days later they go foraging or hunting with their mother. [Source: Rebecca V. Normile, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kathryn Frens wrote in Animal Diversity Web: While the ranges of male and female bandicoots extensively overlap, females likely dictate distribution as they select and defend high-quality habitats for nesting and foraging. While some species, such as northern brown bandicoots create terrestrial nests with an internal chamber, others, such as eastern barred bandicoots make several different kinds of nests, including subterranean chambers that are used during birth.

The accelerated reproductive cycle of Bandicoots results in minimal parental care to young. The unique placenta of bandicoots reduces direct contact between mother and fetus. However, the umbilical cord remains attached for a few hours afterbirth to serve as a safety rope while young leave the uterus and crawl into the rear-opening marsupium. Juveniles may continue to live in the mother’s nest for some time after leaving the pouch, but it is not known if they remain in their mother's nest after weaning. There is no contact between mother and offspring after young leave the nest. Young bandicoots can reach reproductive maturity in as little as four months, however, only 11.5 percent of young survive to adulthood.

Endangered Bandicoots

Three bandicoot and bilby species have gone extinct relatively recently and several are currently facing threats and are listed as endangered or threatened. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, three species of bandicoots and bilby have recently gone extinct, four are classified as Endangered, two are vulnerable, one is near threatened, nine are of least concern, and the remaining three are data deficient. The Golden Bandicoot is listed as vulnerable, both as a species and for its Barrow Island subspecies. The Eastern Barred Bandicoot is listed as endangered in South Australia and Victoria. The Western Barred Bandicoot has a complex listing, with the mainland subspecies considered extinct and the Shark Bay population listed as endangered. Long-nosed bandicoots are classified as least concern on the IUCN Red List, but some localized declines are noted in the southern part of its range.

Threats to bandicoot populations include: habitat loss and degradation through development, agriculture, and other land-use changes. Predation by introduced species, particularly foxes and feral cats, is a major threat to bandicoots, especially in arid and semi-arid areas. Some introduced species such as rabbots compete with bandicoots for resources. Disease outbreaks and fires can also impact bandicoot populations.

The mainland population of Eastern barred bandicoots is listed as endangered. It was previously listed as extinct in the wild, but was reclassified as endangered due to successful conservation efforts. Habitat loss and predation by foxes were major factors in their decline. Southern brown bandicoots are also listed as endangered under both Victorian and Australian legislation. Habitat loss and predation from introduced species like foxes, cats, and dogs, as well as competition from rabbits, contribute to their decline.

Bandicoots, Humans and Conservation

Bandicoots have little direct impact on humans although the giant bandicoot is still hunted by locals for bushmeat trade and for its fur. It was estimated that mean and pely from one animals could be sold for six U.S. dollars in the 2000s. They also sometimes venture into suburban areas and dig up lawns and gardens in search of food. They carry ticks, mites, and fleas, which can be transmitted to domestic animals and humans.[Source:Kathryn Frens, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kathryn Frens wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Species adapted to arid and semi-arid habitats have experienced significant declines since European settlement. A major threat to bandicoots is the changing of fire regimens for agriculture and grazing animals across Australia and New Guinea. As fire regimens change and grazing increases, ground cover becomes reduced and predation increases. By occupying a wide variety of habitats and vegetation types, bandicoots largely avoid competition. However, the introduction of sheep, cattle, and European rabbits has caused many species to become threatened, and in some cases extinct, due to increased competition for resources. Some introduced species carry diseases that can be transmitted bandicoots. For example, toxoplasmosis, which is fatal to many species of bandicoot, was first introduced by cats. The giant bandicoot, which is Endangered, is hunted and sold as food by local people.

Recovery efforts include: 1) Habitat restoration and protection, particularly restoring native vegetation; 2) Predator control, with a focus on reducing populations of foxes and feral cats through trapping, baiting, and other methods; 3) Captive breeding and reintroduction programs; and 4) Raising public awareness and encouraging community involvement in conservation efforts is essential.

Zoos Victoria has played a key role in breeding and reintroduction programs for Eastern barred bandicoots, with populations now established on fox-free islands and fenced mainland sites. For Southern brown bandicoots, captive breeding programs and secure, predator-free habitats are crucial for their survival. The Western barred bandicoots (Shark Bay Bandicoot) is also considered endangered and has been the subject of reintroduction efforts in New South Wales.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025