Home | Category: Animals / Animals / Marsupials

GLIDERS

Glider and possum species: 1) Lemuroid Ring-tailed Possum (Hemabelideus lemuroides), 2) Central Greater Glider (Petauroides armillatus), 3) Northern Greater Glider (Petauroides minor), 4) Southern Greater Glider (Petawroides volans), 5) Lowland Ring-tailed Possum (Pseudochirulus canescens), 6) Weyland Ring-tailed Possum (Pseudochirulus carols)

Gliders are gliding possums. Also called flying possums, they resemble flying squirrels but are not related to them and are found in Australia, New Guinea and neighboring islands. Gliders are primarily nocturnal animals that swoop down out of their homes, usually holes in trees, at dusk and travel from tree limb to tree limb with the help of membranes between their front and rear legs. There are several species. Cat-size great gliders and smaller sugar gliders can volplane, or glide, 100 meter. Each time before they take off they make a low whirring moan. Yellow-bellied gliders, sugar gliders and feathertail gliders feed of sap that oozes out of cuts they make with their claws in eucalyptus trees.

Ten species of glider are found in Australia.

1) Sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps)

2) Krefft's gliders (Petaurus notatus)

3) Savanna gliders (Petaurus ariel)

4) Squirrel gliders Petaurus norfolcensis)

5) Mahogany gliders (Petaurus gracilis)

6) Yellow-bellied glider Petaurus australis

7) Central and southern greater glider (Petauroides volans)

8) Northern greater glider (Petauroides minor)

9) Broad-toed feathertail gliders (Acrobates frontalis) and

10) Narrow-toed feathertail gliders (Acrobates pygmaeus)

Species of glider found in New Guinea

1) Sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps)

2) Northern glider (Petaurus abidi).

3) Guinea glider (Petaurus papuanus)

4) Biak glider (Petaurus biacensis)

Greater gliders are not closely related to the Petaurus group of gliding marsupials (including sugar, mahogany, squirrel and yellow-bellied ones described below). Greater gliders are more closely related to Lemuroid ringtail possums (Hemibelideus lemuroides), which are both in the subfamily Hemibelideinae.

Studies have shown that logging, especially when compounded with exposure to drought and fire, can have a string negative impact on glider species, reducing the habitability of an area. Deep gullies, unaffected by logging, were found to be crucial refuges for gliders. It is recommended that these gullies be maintained and protected in order to conserve habitat for all species of gliders. [Source: Barbara Lundrigan and Melinda Girvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Sugar gliders are commonly kept as exotic pets. Their presence in the pet trade is highly debated. In some places it is illegal to own or sell them. These pet animals are commonly referred to as "sugar gliders", but recent research indicate — at least for American pets — that they are not sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps) but are members of a closely related species, ultimately originating from a single source near Sorong in West Papua. This would possibly make them Krefft's glider (Petaurus notatus), but the taxonomy of Papuan Petaurus populations is still not completely understood. [Source: Wikipedia]

RELATED ARTICLES:

GLIDER SPECIES (SUGAR, MAHOGANY, GREATER, YELLOW-BELLIED): CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

POSSUMS OF AUSTRALIA AND NEW GUINEA: SPECIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BRUSHTAILED POSSUMS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SPECIES, PESTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSCUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSCUSES OF SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

Phalangeriformes

Petaurus Genus of Gliders

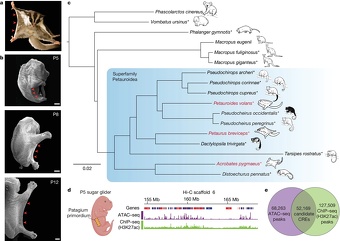

a) An adult sugar glider extending its patagium (red arrowheads) during gliding flight; b) Scanning electron micrograph showing dorsolateral views of P5, P8 and P12 sugar glider joeys; The patagium primordium (red arrowheads) becomes externally visible at P5 and continues to grow and extend in subsequent days; Scale bars, 1 mm; c) Species tree topology estimated from whole-genome data; Phylogeny is consistent with the independent evolution of patagia in three petauroid species (labelled in red font): P breviceps, P volans and A pygmaeus; Species for which we generated genome sequences and assemblies are indicated by asterisks; d, ATAC–seq and ChIP–seq traces from the P5 sugar glider patagium primordium; e) The experimental strategy used to identify the set of candidate cis-regulatory elements used for downstream analyses [Source: Nature]

Most gliders, including squirrel gliders, sugar gliders, and yellow bellied gliders, belong to the genus Petaurus, also known as the lesser gliding possums. Their patagium (gliding membrane) of these animals connects from their front feet to their back ankles. They are capable of changing their direction and speed as when they glide from tree limb to tree limb. They also have opposable thumbs to assist in climbing trees and eating. Recently, they have been reclassified into eight distinct species. [Source: Audrey Bowman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The genus Petaurus is part of the clade Diprotodontia which consists of the "classic" marsupials like kangaroos, koalas, and wallabies. They are further classified as a part of the family Petauridae, which contain the arboreal possums of Australia. The subfamily Petaurinae originally included genus Petaurus with genus Gymnobelideus. Later research concluded that genus Gymnobelideus was more closely related to genera in other subfamilies. Members of Petaurinae have many common features such as three single-cusped upper pre-molars and slightly curved procumbent lower incisors. Although in separate sub families, Petaurus' closest relatives are other members of Petauridae like Gymnobelideus leadbeateri, and members of genus Dactylopsila.

The genus Petaurus is believed to have originated in New Guinea during the mid Miocene epoch, approximately 18 to 24 million years ago. The modern Australian Petaurus, along with New Guinean members of what were formerly considered sugar gliders diverged from their closest living New Guinean relatives nine to 12 million years ago. They probably dispersed from New Guinea to Australia between 4.8 and 8.4 million years ago, with the oldest Petaurus fossils in Australia being dated to 4.46 million years. This may have been possible due to sea level lowering from about 7 to 10 million years ago, resulting in land bridges between New Guinea and Australia. [Source: Wikipedia]

The lifespans of Petaurus gliders in the wild has not been widely researched. In captivity they have been recorded to live as long as 17.8 years. Yellow-bellied gliders are known to have lived at least six years in the wild. Since Sugar gliders have become a popular exotic pet, their captive lifespan is generally around 10 to 12 years, though they are considered old when they are five to seven years old, implying that is be close to their maximum lifespan in the wild.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has information on a few of the Petaurus species. Populations of sugar gliders, the most researched of members of Petaurus genus are and stable. On the IUCN Red Lest they are listed as species of least concern. Yellow-bellied gliders, northern gliders, squirrel gliders, and mahogany gliders are all have decreasing populations, and are at classified at varying levels of concern. Yellow-bellied gliders are considered near threatened; Northern gliders are Critically Endangered; Squirrel gliders are listed as least concern; and Mahogany gliders are Endangered. The IUCN has little information Biak gliders but they are considered a species least concern with unknown population as of 2015. The main threats to these animals are habitat destruction due to logging industries and urban expansion.

Their main known predators of Petaurus gliders are various quoll species, carpet pythons and goannas (monitor lizards) Species within the Petaurus this genus have very complex calling and chemical communication systems. They have specific alarm calls and maintain a home range with their community to keep in contact with each other for protection. In their region, the main predators are feral dogs and cats, owls, foxes, quolls, and a few larger, reptiles, such as goannas and pythons. |=|

Glider Habitat and Where They Are Found

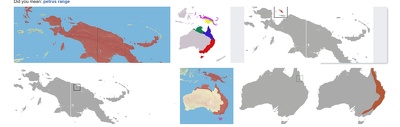

Top row (left to right): 1) Guinea glider (Petaurus papuanus); 2) formerly recognized subspecies of sugar glider: A) P. b. breviceps (introduced in Tasmania) (red); B) P. b. longicaudatus (blue); C) P. b. ariel (now recognized as the species Savanna glider (Petaurus ariel) (olive green); D) P. b. flavidus (yellowish green); E) P. b. tafa (green); F) P. b. papuanus (purple); G) P. b. biacensis (now recognized as Biak glider (Petaurus biacensis)(black) 3) Biak glider

Bottom row (left to right): 1) northern glider; 2) sugar gliders; 3) mahogany glider; 4) squirrel glider

Different species of gliders reside in Australia, New Guinea, and other surrounding islands. There is some overlap in the species’ range, which in the past has resulted in some incorrect classifications. Most live relatively near coasts, where there is more vegetation, and likely all originated in Australia before reaching and colonizing the nearby islands. [Source: Audrey Bowman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The eastern coast of Australia is home to squirrel gliders, mahogany gliders, yellow-bellied gliders, Krefft’s gliders, and sugar gliders. Northern gliders resides mainly on the island of New Guinea and savanna gliders resides mainly in the northwestern coastal region of Australia. In addition, Biak gliders predominantly inhabits Biak Island, just north of New Guinea.

Gliders live mainly in forests and rainforests but also live in wooded savannas (the savanna glider). They evolved in an area where incomplete canopies were dominant, and their gliding membranes helped them get from tree to tree. Since they are also great climbers, most of their time is spent up in the canopy of the eucalyptus trees, away from predators and then only glide down when they have a reason to. Their omnivorous (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals) diet works well with this habitat since they get most of their nutrition from nectar, sap, and insects which are found in the trees.

Glider Characteristics

Gliders are best known for their gliding membrane — their patagium — that stretches from the front to hind limbs and connects to the body and limbs from their front feet to their back ankles. They are larger than most flying squirrels. The heads and bodies of gliders range from 12 to 32 centimeters (4.7 to 12.6 inches) and their tails range from 15 to 48 centimeters (5.9 to 15.9 inches). The largest, yellow-bellied gliders, weigh 435 to 710 grams (15.3 to 25 ounces). The smallest, sugar gliders, weigh only 79-160 grams (2.8 to 5.6 ounces). Skull size has been used to classify different species and was recently used to support the splitting of sugar gliders into distinct species. [Source: Audrey Bowman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

There are several features that distinguish gliders from other gliding mammals. One of the main ones is they often have semi-prehensile and fully-furred tails that flying squirrels don’t have. Also female gliders have pouches. They also have large, forward-facing eyes and short, pointed) faces. Their long flat tails serve as rudders while gliding.

Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is generally not present in gliders: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. There are a few morphological difference between the sexes. Males have bare patches on their head and throat where secretions can more effectively be released. The pouches of all species are fully formed, but Yellow-bellied gliders have a well-furred septum dividing its pouch into two compartments. Juveniles don't differ greatly from adults, their fur just being more downy and slightly longer than most adults.

All species of Petaurus genus gliders have countershading, mostly grey on their back side and lighter coloring on their undersides Yellow-bellied gliders differ in that they are browner in color on the back side, and are an orange-yellow color on their bellies, the source of their common name. Many species have a dark dorsal stripe that extends from their nose to the base of their tails. This stripe varies in thickness across the body and can vary from individual to individual. Most species also have have dark fur around their eyes and ears that generally connects around the nose. This darker fur can also be found on the upper side of their forelimbs and occasionally on the hindlimbs.

Glider Behavior and Diet

Gliders glide and are arboreal (live mainly in trees), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They generally rest in tree hollows in the day and come out at night. Dominant males survey the area more, keep up territory protection and organize the rest of the group. [Source: Audrey Bowman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

When environmental conditions are harsh, gliders are able to achieve temporal heterothermy for up to 16 hours a day. Temporal heterothermy refers to the ability of an animal to switch between being a homeotherm (maintaining a constant body temperature) and a poikilotherm (allowing body temperature to fluctuate with the environment) at different times. This often involves entering a state of torpor or hibernation to conserve energy when resources are scarce or environmental conditions are harsh.

Gliders communicate with sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Dominant males mark their territory with scent. Gliders have a few unique calls. Those of yellow-bellied gliders are the most studied. have specific calls for different predators, and ones to define their territory to intruders. Gliders have good vision and other adaptations for nocturnal living.

Petaurus gliders are generally omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals), feeding on what is available in their environment. Eucalyptus of various species is available across the majority of their range and feed on the sap which they often extract like rubber tappers — cutting into the tree with their claws and consuming crystallized sap that oozes out and hardens. They will also feed on nectar and pollens of various flowering plants and insects they find in tree bark. Occasionally they feed on small birds and smaller mammals.

The patagium of gliders is used to glide from tree to tree when foraging. Mahogany gliders, spends approximately 44 percent of their foraging for food. While being relatively small, they will aggressively protect a food sources and their nests from larger animals meal, using their claws and teeth.

Glider Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Gliders are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). They engage in seasonal breeding and year-round breeding. Gestation ranges from two to three weeks, Parental care is provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. [Source:Audrey Bowman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Gliders nest in groups of up to seven males and females and their offspring. One or two dominant males do most of mating. Audrey Bowman wrote in Animal Diversity Web: The dominant males are generally heavier, have higher testosterone, and lower cortisol. Mating is done in some monogamous pairs, but when food is abundant, polygynous units are popular. Breeding time is variable depending on species and range, some have specific cycles, while others breed year round when their circumstances allow. They have a 29 day estrus cycle, with generally only one to three young per female, depending on the species. If the first litter is lost or weaned, and if it is still during the breeding period and resources are abundant, the mother can have a second litter.

Since the dominant male does the majority of the mating, courting behaviors are not common. In monogamous pairs, males spend around half of their active time within 25 meters of their partner, and 55-85 percent of their sleeping time with their female partner. Having a larger body mass contributes to higher reproduction rates but less flying efficiency so balancing these features is necessary in their reproductive physiology.

Young climb into their mother’s pouch after birth and attach themselves to a nipple inside the the pouch. They spend around six weeks attached to the nipple, emerges from pouch at around 10 weeks, leave the nest after another six weeks and are then relatively independent. They reach sexual maturity at about a year, a little less for females, a little more for males, and are producing young until around eight years of age. Gliders have a relatively low infant mortality rate.

How Gliders Developed Their Ability to Glide

Several marsupial species, including sugar gliders, independently evolved a way to make membranes that allow them to glide through the air. This ability has evolved at least three times independently in closely related glider species, including sugar gliders. But scientists have long been puzzled by how it evolved. In 2024, a team of researchers announced that they had uncovered the genetic basis for the evolution of this novel adaptation: a gene called Emx2, which plays a critical role in making the patagium. [Source: Viviane Callier, Scientific American, April 24, 2024]

Viviane Callier wrote in Scientific American: In sugar glider babies (which are called joeys and live in their mother’s pouch for several weeks after birth), Emx2 is expressed in the skin on the left and right flanks, where the gliding membrane will form. The activity of this gene is required for the normal development of the patagium: when researchers repress the gene, the patagium fails to form properly. Surprisingly, the researchers discovered that Emx2 is also expressed on the flanks of developing lab mice but only transiently, whereas in the sugar gliders, the gene remains active for much longer. Although it is not known why the gene is expressed temporarily on the flanks of developing mice, Emx2 is known to have important roles elsewhere: it is essential for brain and bone development, where it is involved in cell proliferation.

To investigate how sugar gliders’ patagium evolved, evolutionary developmental biologist Ricardo Mallarino of Princeton University and his then graduate student Jorge Moreno teamed up with Olga Dudchenko and Erez Lieberman Aiden of Baylor College of Medicine, along with other collaborators in the U.S. and Australia, to sequence the genomes of 15 marsupial species. These included old specimens from museum collections, some of which were endangered species. Several of the marsupials had a gliding membrane, and some did not. By comparing the genomes of gliding and nongliding marsupial species, the researchers could identify regions of the genome that evolved faster in the gliding species than in the nongliding ones. The results were published April 24, 2024 in Nature.

The team identified more than 1,000 regions on the marsupials’ genome that showed accelerated evolution, or faster rates of DNA mutations, in the gliding species (and thus were candidates for genetic changes that could contribute to the evolution of the gliding membrane). But not a single “glider accelerated region”—one that exhibited an accelerated rate of mutations—was shared across all three gliding species studied. At first that was a disappointment because there was no smoking gun—no clear gene candidate to go after. But after more thought, the team realized that many of these glider accelerated regions were regulating the activity of other genes and that it was possible to computationally infer the target genes that each of these regions were regulating. Furthermore, the researchers knew which genes were activated in the developing patagium from previous work. When they focused on genes activated in the patagium that were regulated by the accelerated regions in all three species, a single gene stood out: Emx2, a transcription factor that orchestrates the activity of many other developmental genes.

“Each individual species is experiencing their own evolution,” says Moreno, now a postdoctoral fellow at the Stowers Institute in Kansas City, Mo. “What we think is going on is that they’ve converged around this key developmental gene that they can deploy in a way that essentially achieves the same outcome. But the way you get to that outcome can be different. That’s what these different enhancer evolutions show us.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “How Sugar Gliders Got Their Wings” by Viviane Callier scientificamerican.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025