Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

ORO PROVINCE

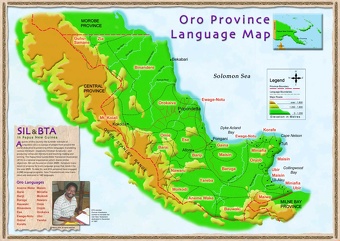

Oro Province— officially still known as Northern Province — lies on the Papuan Peninsula in southeastern Papua New Guinea. Covering 22,800 square miles (8,778 square miles), it had a population of 176,206 in the 2011 census and borders Morobe, Central and Milne Bay provinces. The capital of Oro Province is Popondetta.

Oro is the only province where the Anglican Church is the dominant denomination. Oil palm is the main industry. The province includes the northern terminus of the Kokoda Track at the village of Kokoda. During World War II, once the Kokoda Track opened access from Port Moresby into the interior, Oro’s northern coast became a major battleground, especially in the Buna, Gona, and Sanananda campaigns.

Oro Province is also where the active volcano Mount Lamington is located. In January 1951, Mount Lamington erupted catastrophically, sending ash 15,000 meters into the air, destroying villages and vegetation, and killing nearly 3,000 people. On the north coast, the Tufi resort in the Cape Nelson Rural LLG is renowned for diving and its dramatic rias—locally called “fjords.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOTU — THE PORT MORESBY AREA PEOPLE — AND THEIR HISTORY, CULTURE, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GEBUSI, PURARI, OROKOLO ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MEKEO, MAILU, WAMIRA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

KALULI (BOSAVI): HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

NINGERUM PEOPLE OF CENTRAL NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

Orokaiva

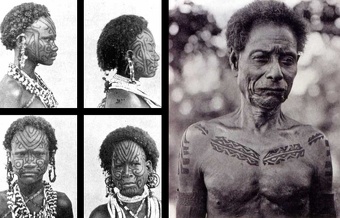

The Orokaiva are a group of culturally similar people living in the Oro Province of Papua New Guinea. They are also known as Aiga, Binandele, Hunjara, Mambare and Wasida, they are primarily an inland, agricultural society organized around village life and the authority of elders. Historically noted as formidable warriors, they also practiced distinctive female coming-of-age tattooing. Today, Orokaiva communities are strongly shaped by Protestant Christian influence. [Source: Christopher S. Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

According to the Joshua Project, the Orokaiva population in the 2020s is about 71,000. In the 1990s, roughly 26,500 of Popondetta’s 36,500 Indigenous residents were Orokaiva, though their numbers at the time of first Western contact are unknown. The term Orokaiva was introduced by Westerners; traditionally, groups identified themselves more specifically as Umo-ke (“River People”), Eva-Embo (“Salt-Water People”), or Periho (“Inland People”). The Orokaiva are concentrated in the Popondetta district, from the coast near Buna to the northern slopes of Mount Lamington and northward. Their homeland is a humid, tropical lowland with year-round agricultural potential. The wet season (December–March) brings high temperatures, humidity, and afternoon storms, while the dry season (May–October) is cooler with patchier rainfall.

Language: Orokaiva belongs to the Binandere (Binandele) language family, a group of eight related languages spoken across much of central Oro Province. Orokaiva is used by about half the population in the Orokaiva–Binandere region. Dialect differences within the Orokaiva area are relatively minor, roughly matching the boundaries of the Higaturu Local Government Council. While vocabulary varies considerably among Binandere languages, their grammar is closely related, allowing limited intercommunication.

History: Before European contact, aggression against members of other tribes took the form of organized raids, which were often accompanied by cannibalism. There were customary restrictions upon feuding within the tribe. Formerly, violent official legal penalties were meted out to criminals. Fear of the ancestors and the desire to avoid unfavorable public opinion remain major mechanisms of social control. ~

European involvement intensified after gold discoveries in the late 19th century. Relations between Papuans and miners were often violent. Papua was annexed by Britain in 1888 and transferred to Australian administration under the Papua Act of 1905. Australian authorities pursued a policy of “peaceful penetration,” introducing social and economic measures and appointing village constables as intermediaries between the government and local communities. The catastrophic eruption of Mount Lamington in 1951 destroyed many Orokaiva settlements, killing thousands. Survivors received government relief and were housed in evacuation camps. From around 1960, major development programs reshaped the region, including the introduction of cash crops, agricultural extension services, land-title reforms, improved roads, and expanded education.

Orokaiva Religion and Culture

While traditional beliefs persist, most the Orokaiva people now identify as Protestant Christians. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 99 percent of Orokaiva are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent. Before missionization, Orokaiva religion centered on the spirits of the dead and their influence on the living. They had no high god and practiced a form of animism, believing that humans, animals, and plants possessed souls (asisi). The taro spirit was especially important and became the foundation of the influential Taro (Kava Keva) Cult. Even with strong Anglican influence in the Northern District, traditional ideas have not disappeared, creating a distinctive blend of Christianity and indigenous spirituality. [Source: Christopher S. Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

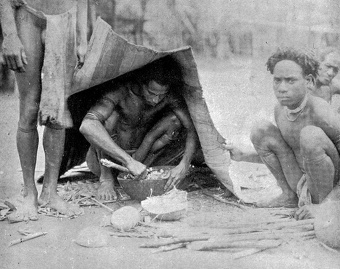

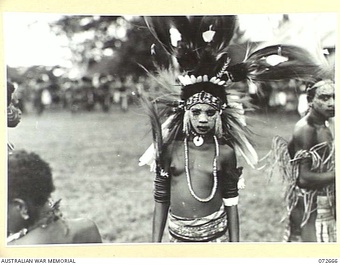

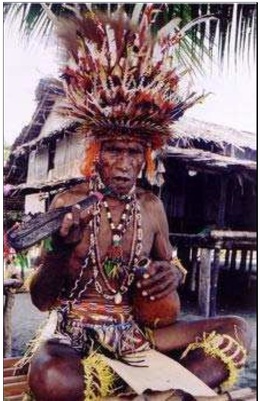

Ceremonies and Ritual Life: The Orokaiva were once renowned warriors, often portrayed with large stone axes, spears, and other traditional weapons. Young women traditionally received facial tattoos at maturity, marking readiness for marriage. Dances are frequent and accompanied by singing and drumming. At times, bigmen sponsor large redistributive feasts featuring pig sacrifices and communal food distribution. The major ritual system, beginning around 1915, evolved into a fertility and ancestor cult aimed at placating the spirits of the dead (sovai) who were believed to control taro productivity. Rituals led by taro men involved choral singing, intense drumming, feasting, and vigorous shaking movements.

Religious Practitioners and Healing: Taro men function as shamans, healers, weather magicians, and sorcerers. Illness and misfortune may stem from angry spirits, sorcery, or natural causes. Because sickness is seen as a foreign substance entering the body, cures focus on removing this intrusion—using pungent odors, rubbing, or sucking out the offending element. Practitioners with sivo (“special power”) are responsible for these treatments.

Death and Funerals: At death, the soul becomes a sovai. These spirits initially linger in the village before moving to places associated with the dead—such as rock outcrops or stagnant pools. Sovai discipline wayward kin by causing illness, misfortune, or death. Although death is explained with matter-of-fact realism, it is ultimately viewed as supernaturally caused.

Art and Music: The Orokaiva decorate tools and ceremonial objects with both abstract and figurative designs. Music holds a valued place in their culture; in former times they crafted wooden drums and pipes, conch-shell and wooden trumpets, and bamboo jew’s harps.

Orokaiva Family and Kinship

The household—made up of either a nuclear or extended family—is the basic domestic and economic unit among the Orokaiva. Children who misbehave are disciplined through scolding and sometimes beating. Most formal education is provided through mission schools, partly supported by the government. Inheritance is generally patrilineal, passed through the male line. [Source: Christopher S. Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

Marriage: Polygyny is permitted but uncommon. Clan exogamy is preferred—ideally marrying outside one’s clan or village—though this rule is not strictly enforced. Villages themselves are not strictly exogamous. Arranged marriages require a substantial bride-price, and in earlier times wives could also be taken by capture. Postmarital residence is ideally patrilocal, but in practice couples may choose to live with the husband’s or wife’s relatives or with affines, and may shift residence as circumstances change. The widespread placement of clan branches across several villages is linked to access to land, often influencing long-term decisions about where to settle. Divorce is permitted; fathers usually gain custody of young children, except infants.

Kinship: Every Orokaiva person belongs by birth to the father’s clan. Members claim descent—often more symbolic than traceable—from a named founding ancestor. Each clan contains named subclans or lineages, each tracing its origin to its own ancestor. Orokaiva kin terminology follows the Iroquois system (bifurcate merging). 1) A father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters are addressed with the same terms as Father and Mother. 2) A father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers use different, non-parental terms (equivalent to “Aunt” and “Uncle”). 3) Parallel cousins (children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister) are classified as siblings. 4) Cross cousins (children of a brother and sister) are distinguished from siblings and are referred to with terms equivalent to “cousin.”

Orokaiva Society and Political Organization

Orokaiva society is marked by flexible rules for group membership and for the transmission of land rights. Most villages contain multiple clan branches, so a village is not necessarily a single landholding unit. People may have stronger kinship ties with relatives in other villages than with some of their neighbors. Even so, shared residence creates a sense of community and solidarity, reinforced by government policies that treat villages—rather than descent groups—as the main administrative units. [Source: Christopher S. Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Marriage between different clan branches within a village also strengthens village cohesion, expressed through daily food sharing, cooperation in work, and joint participation in rituals. A typical lineage includes about three households. Villages usually contain several clans, and members of any one clan are often spread across multiple neighboring settlements. Lineages, by contrast, tend to be more localized, often confined to a single village and occupying a particular section of it.

Orokaiva political life has no centralized authority and no hereditary leadership. Instead, influence rests with big-men (embo dambo) and respected elders who have proven themselves through generosity, hard work, wealth, sound judgment, and skill in organizing ceremonies. Their authority is moral rather than coercive; they cannot impose sanctions. There are roughly twelve Orokaiva tribes, each a loose political unit with no overarching leader. The tribe is the largest sociopolitical grouping, occupying a shared territory typically separated from neighboring tribes by tracts of uninhabited land.

Land Rights may be held by a clan branch, a lineage, or an individual, and the importance of each level varies by region and population density. Multiple descent groups may claim rights to the same land. Often the clan branch serves as the reference group for associating land, and in some areas it also serves as the primary right-holding group for hunting lands, such as grasslands. Garden land, however, is normally controlled by the lineage. Ultimately, land rights can usually be traced to individuals, who may distribute portions of land or other property before death to immediate family and more distant relatives. Traditional tree crops are scattered rather than planted in stands, and may grow on patrimonial land, affinal land, or land associated with matrilateral kin. Inheriting rights to trees does not necessarily confer rights to the land on which those trees stand.

Orokaiva Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The Orokaiva live in small villages, usually arranged around a central earth or grass square. on flat, carefully maintained clearings where grass is trimmed and rubbish is removed. Most villages have populations under 720 people. Houses, built by men, are spaced in a roughly rectangular layout around the square and typically shelter a single nuclear family. Bachelors’ houses, similar in size and construction, are also built. [Source: Christopher S. Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Orokaiva rely primarily on agriculture, with gathering and some hunting supplementing the diet. Their humid lowland environment supports a year-round growing season, and households serve as the main units of both production and consumption. Swidden (slash-and-burn) agriculture is the foundation of subsistence. Taro is the dominant crop, occupying about 90 percent of cultivated land. Other crops include bananas, sugarcane, edible pitpit, and introduced plants such as pineapple, tomatoes, beans, and sweet potatoes.Traditional arboriculture—coconut, sago, betel nut, and other trees—was relatively modest compared with the intensive attention given to taro. Under Australian influence, the Orokaiva adopted rubber, coffee, and coconut palms (for copra), which now provide important cash incomes.

Gathering remains vital, especially in the surrounding rain forest. Foraged foods include grubs, frogs, snails, rats, bush eggs, as well as leaves, roots, and fern fronds—particularly valued during the dry season. Fish are crucial both for food and for trade. Hunting plays a smaller role, focusing on small marsupials, birds, and pigs. The Orokaiva keep pigs, dogs, and fowl, though pigs are declining due to government hygiene campaigns. Dogs serve for hunting and later as food; fowl provide meat, eggs, and decorative feathers.

Work is highly gendered, with cooperation occurring mainly within sex-based tasks. Men hun,t build houses, make tools and equipmen, process sago, plant all crops (traditional and introduced), maintain yams and rubber, harvest rubber and market coffee Women cook, care for the sick, maintain taro and sweet potatoes, harvest taro, market root crops, both men and women:, fish, build fences, collect firewood, maintain and harvest coffee and market rubber. Cooperative projects involving an entire village are rare, but joint hunting and fishing expeditions do occur.

Orokaiva artisans produce rafts and canoes, pottery, bark cloth (tapa), mats and baskets of coconut or pandanus leaves, wooden bowls, musical instruments, and a range of weapons. Traditional intertribal trade centered on animal products, betel-nut goods, feathers, and high-quality specialty artifacts from certain districts. Although modest in volume, trade played an important political role, often helping to end hostilities between groups.

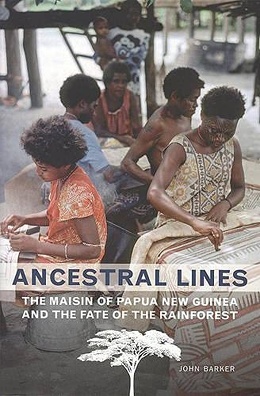

Maisin

The Maisin live in Oro Province. Also known as the Kosirau, Kosirava, and Maisina, they mostly reside in small villages scattered along the southwestern shores of Collingwood Bay, with one outlier community (Uwe) on Cape Nelson. Their settlements are far from major roads and markets, and the people rely on both land and sea—using the surrounding rain forest for swidden gardens, hunting, and materials for houses and canoes. Although their villages appear “traditional,” the Maisin have long been integrated into wider Papua New Guinea society. Internationally, they are best known for their finely painted bark cloth (tapa). [Source: John Barker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

Maisin communities occupy three areas in the Tufi Subdistrict. The Kosirau live in isolated settlements deep within the Musa River swamps. A second group shares Uwe village with Korafe speakers on Cape Nelson’s northeast coast. The majority live in eight villages along southern Collingwood Bay. Except for the more remote Kosirau, all identify simply as Maisin. Early Western accounts used the names Kosirava and Maisina for these groups. Behind the coastal settlements stretches an extensive, uninhabited region of forest, swamp, and mountains. The area remains highly isolated, accessible only by boat or by small aircraft landing on grass airstrips. The annual cycle includes heavy northwest monsoon rains from November to April and a drier, cooler southwest season beginning around May.

According to the Joshua Project, the Maisin population in the 2020s was about 5,300. The 1980 National Census recorded roughly 2,000 Maisin, with about 1,400 living in rural villages and the rest in towns. Today, a quarter or more live in urban centers, and their remittances are vital to the village economy.

Language: Maisin is the primary language. Two dialects are spoken: Maisin and Kosirava. The language attracted early scholarly interest as a rare example combining Austronesian and Non-Austronesian grammatical features, leading some researchers to classify it as a “mixed” or even “Non-Austronesian” language. Schools established by the Anglican mission in 1902, now government-run, have produced high literacy, and most adults speak basic English and Tok Pisin in addition to their own language.

Maisin History

Archaeological evidence indicates that southwestern Collingwood Bay has been inhabited for at least 1,000 years, with long-distance trade links to Goodenough and the Trobriand Islands. Maisin oral tradition holds that their ancestors emerged from underground several generations ago at the western edge of the Musa Basin. Those who remained became the Kosirau; others moved along coastal and inland routes to their current locations. [Source: John Barker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

At European contact in 1890 the Maisin were known as fierce warriors who raided by canoe. Warfare and raiding were common until around 1910. Maisin elders speak nostalgically of great warriors from the past. However, the only major conflict that living Maisin have witnessed was the one between the Japanese and the Allies during World War II. Today, most conflicts occur over land or sorcery accusations and rarely involve violence.

Colonial control began when British New Guinea established a station at Tufi in 1900 and suppressed intertribal warfare, and the Anglican mission opened a church and school at Uiaku in 1901. Over the next decades, most young people converted to Christianity, and men increasingly worked on distant plantations and mines. During World War II, although Collingwood Bay lay outside the Japanese invasion zone, all able-bodied Maisin men served as laborers for Australian forces. After the war, integration into national life accelerated; many pursued secondary and tertiary education and joined the professional workforce, while those at home experimented (mostly unsuccessfully) with small cash crops.

In the 1990s, the Maisin became nationally and internationally known for their environmental activism. Aligning with groups such as Greenpeace, they challenged illegal logging claims in their rainforests and promoted small-scale, sustainable development. Their legal victory in 2002 against a logging company drew international attention, though logging and mining pressures persist and opinions within the community remain divided. In 2007, catastrophic floods across Oro Province destroyed many Maisin gardens and damaged village housing.

Maisin Religion and Culture

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 95 percent of Maisin are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent. The Maisin have traditionally believed that the spirits of the recently deceased continue to influence the living, for both good and ill. Encounters with bush spirits are considered dangerous and can cause serious illness, especially among women and children. Despite attempts to suppress sorcery, most Maisin think that various forms persist—practiced by both villagers and outsiders—and they attribute many deaths to sorcery. [Source: John Barker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

God and Jesus are regarded as distant beings who may appear in dreams, yet faith in them is believed to protect against harmful spirits and sorcerers. With few exceptions, the Maisin are Christian: most coastal communities are second- or third-generation Anglicans, while the Kosirau converted to Seventh-Day Adventism in the 1950s. Although villagers embrace Christian teachings and worship, they also continue to acknowledge local spirits and ghosts and maintain practices such as garden magic and indigenous healing. Beliefs vary widely depending on education and experience outside the villages.

Religious Practitioners: Six Maisin men have been ordained as Anglican priests, and many others have served as deacons, religious brothers and sisters, teacher-evangelists, lay readers, and mission medical workers. Since 1962 the Anglican Church in the area has been fully indigenized and led by a local priest. Nearly every village also has healers—men and women with specialized knowledge of plant medicines, bush spirits, and the interactions between human souls and the spiritual realm. Illness may be attributed to “germs,” spirit attack, or sorcery, depending on whether it responds to Western treatment. Villagers use government medical aid posts and a regional hospital alongside home remedies and traditional healers.

Ceremonies and Healing: Before European contact, major ceremonies included funerals, mourning rites, initiations of firstborn children, and large intertribal feasts. These events involved extensive exchanges of food, shell valuables, and tapa cloth, and initiations and feasts often featured days or weeks of dancing. Today, the central communal celebrations are Christmas, Easter, and local patronal feast days, all of which may include major feasts and traditional dancing in local costume. Important life-cycle rituals, particularly firstborn puberty rites and mortuary ceremonies, remain key ceremonial occasions.

Death and Funerals: Traditionally, spirits of the dead were believed to dwell in the mountains behind the villages and to return frequently to help or punish their kin. Villagers still experience dreams and visions of the recently deceased, attributing good fortune or misfortune to them, though they now say that the dead reside in Heaven. Mortuary rituals—though reshaped by Christianity—remain the most visibly “traditional” aspect of Maisin culture. For three days after a burial the community mourns collectively, keeping quiet and avoiding garden work so as not to disturb the spirit or its relatives. Spouses and parents observe periods of semiseclusion, lasting from days to several years. Their affines eventually bring them out of mourning in a rite closely resembling firstborn puberty ceremonies, washing them, trimming their hair, and dressing them in clean tapa and ornaments.

Art and Tattoos: Maisin women are widely renowned for producing beautifully painted tapa (bark cloth). Once the traditional clothing of both men and women, tapa remains central to ceremonial exchange and provides an important source of cash income, sold through church and government channels to urban artifact markets. In the past most women received distinctive facial tattoos in late adolescence, featuring curvilinear designs that cover the entire face and are unique to the region.

Maisin Family and Kinship

The basic economic and social unit among the Maisin is the household, typically centered on a nuclear family that gardens and eats together. Households are often enlarged by parents, grandparents, adult siblings, aunts, uncles, and other close kin. As older relatives become less able to work, their children may build small satellite houses where they live in partial seclusion. Infants and children are raised collectively by parents, close kin, and siblings, with older children caring for younger brothers, sisters, and cousins. Adults guide children through example and gentle correction, with punishment used rarely. From about age six or seven, children spend much of their time in school. [Source: John Barker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

In earlier times all boys underwent brief initiations into their patriclans, and elaborate rites were held for firstborn children of both sexes. These major ceremonies still occur occasionally. Many Maisin girls continue to receive facial tattoos during puberty, though such practices are declining as more youth attend distant high schools or leave the villages for work in town. Ritual property is generally given to the eldest child—especially the eldest son. Sons inherit land equally, while married daughters may garden their father’s land but cannot pass this right to their children.

Marriage has traditionally taken place with a partner who lived within the vicinity of one’s home villages, but always outside their own clan. Sister exchange was traditionally preferred because it required no bridewealth, though such arrangements often broke down. These traditions have become less the norm as migration to towns has became common. But as in the past, individuals today exercise considerable choice in marriage partners. Premarital relationships are common, and many people live with several partners before settling into a long-term union, often after children are born. Husbands are expected to provide bridewealth, and both spouses should make formal presentations to the wife’s kin to mark the birth and maturation of their firstborn. Many villagers note that these obligations are now frequently delayed or ignored. Some couples marry in church early, but most wait—sometimes until after they have children—before seeking a priest’s blessing. Newly married couples usually stay with the husband’s clan relatives before building their own house in the patriclan hamlet. Although the church discourages divorce, it is common and informal. Monogamy prevails, but a few polygynous marriages exist in most villages.

Kinship: Patriclans living in hamlets within the village are the most stable kin groups. Their size and composition vary widely: some consist of a single lineage, while others include several named subclans occupying different sections of a hamlet or separate hamlets. Clans with land in different settlements often share close historical ties. Patriclan identity is expressed through land claims, emblems (such as tapa designs, ritual practices, magical traditions, lime-spatula motifs, and body ornaments), and origin or migration stories. The Maisin distinguish two clan ranks—the higher-ranked kawo and the sabu. Kawo clans traditionally held certain ritual privileges, such as hosting feasts and dances in their hamlet plazas and wearing specific ornaments like chicken feathers. Whatever significance these ranks once held in times of warfare and intertribal feasting, they have little practical importance today. In everyday life, patriclans matter less than flexible networks of close cognatic kin and affines who form work groups and assist in ceremonies and exchanges. Descent is formally patrilineal, though—like much of Melanesia—many exceptions occur.

Kinship Terminology follows the Iroquois (bifurcate-merging) kinship system, which distinguishes both gender and the parental generation’s same-sex versus cross-sex siblings. A father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters are addressed with parental terms (“father,” “mother”), while a father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers are labeled with non-parental terms (“aunt,” “uncle”). Parallel cousins—the children of these same-sex siblings—are considered siblings. Cross-cousins—the children of a father’s sister or a mother’s brother—are not regarded as siblings and are referred to with separate cousin terms. [Source: Wikipedia]

Maisin Society

The Maisin live in a largely egalitarian society in which kinship obligations—expressed through continual informal and formal exchanges—help equalize differences in wealth and influence. These obligations also ensure support for the elderly and those in need. People who act too independently or set themselves above others are generally frowned upon. Even so, certain relationships carry recognized authority: parents over children, elders over younger people, kawo clans over sabu clans, wife givers over wife takers, and men over women. Social order is maintained primarily through informal sanctions such as gossip, community expectations of respect and equality, and the powerful cultural fear of sorcery. When informal measures fail, the entire village may convene to address the issue, and serious cases can be taken to the subdistrict government court. [Source: John Barker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Political Organization: Maisin distinguish three arenas of political life: the “village side,” the “mission side,” and the “government side.” Village side affairs include life-cycle ceremonies, exchanges, and disputes over land or sorcery. These matters are handled among kin groups, with patriclan elders playing central roles. The mission side includes church councils and Mothers’ Unions, which provide moral and financial support to clergy and teachers. The government side encompasses the activities of the Local Government Council and village business groups that promote development and organize for provincial and national elections. Often, the same men become leaders in all three domains, drawing on their personal authority, education, and experiences outside the rural area. Senior women exert indirect but significant influence, particularly in village- and mission-related matters, though men dominate formal public politics.

Land Tenure: Low population density and a moderate climate provide the Maisin of southern Collingwood Bay with abundant land for subsistence. Land is generally inherited through the male line, although people often cultivate gardens on the lands of affinal and matrilineal relatives. Patriclans also hold claims to extensive areas of forest, grassland, and sometimes stretches of coastline.

Maisin Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The Maisin have traditionally practiced shifting, slash-and-burn agriculture, moving their gardens every two to three years. Their staple foods include taro, sweet potatoes, plantains, and sago, supplemented by coconuts, papayas, sugarcane, watermelons, squash, and sweet bananas. Gardening is done with digging sticks and machetes. Villagers rely heavily on fish and shellfish, collected by hand, line, net, and spear. They also hunt wild pigs, cassowaries, wallabies, and birds in the surrounding forests using spears and, increasingly, shotguns. Store-bought items such as white rice and tinned meat and fish round out the diet. Chickens, dogs, and cats are kept, although pigs were banned from villages by the Local Government Council in the mid-1960s. A small commercial trade exists for copra and a larger one for tapa, but most cash and store goods come from relatives working in towns. [Source: John Barker, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Work is strongly gendered. Men clear and burn garden plots, build fences against wild pigs, and assist with planting. They also hunt, fish, and construct houses and canoes. Women plant, weed, and harvest the gardens; gather wild foods; carry firewood and produce back to the village; and prepare meals. They also weave string bags and make tapa. Both men and women participate in sago preparation, often working together.

In the 1990s, the nine coastal villages varied in size from under 100 to more than 300 residents. Most stand in clusters of two or three neighboring communities, and populations fluctuate as people move between villages and town. While a few villages are formed around a single kin group, most consist of multinucleated settlements made up of patriclan hamlets stretched along the shore. Typically, hamlets are arranged in two roughly parallel lines facing the water, though higher-ranking clans may occupy circular house arrangements around a central plaza used traditionally for dancing and feasting. Footpaths link hamlets to gardens, fishing areas, and nearby settlements.

The three largest villages contain simple churches, schools (with teacher housing), medical aid posts, and small community trade stores. Before foreign contact, Maisin houses were built on mangrove posts 3–4 meters above the ground, with a lower platform for cooking and work and an upper room reached by ladder for sleeping. Since the 1920s, houses have followed colonial-influenced designs—rectangular structures with windows and verandahs—though still raised on posts and mostly made of bush materials. From the mid-1980s onward, some families, supported by remittances, began building houses with metal roofs.

The Maisin continue to produce much of their material culture, including string bags, tapa cloth, houses, and outrigger canoes. Certain items—such as clay cooking pots—are purchased from neighboring groups. Increasingly, factory-made goods have replaced handmade ones, particularly clothing, nets, and household utensils. In early colonial times, the Maisin exchanged tapa, stone axe blades, and food for shell valuables and obsidian with groups on Cape Vogel and Goodenough Island. Today, they still trade occasionally with interior groups for net bags, dogs, and feathers, and with the Wanigela for pottery. Payment may be in tapa, though cash is more common. Small household-based trade stores sell tobacco and a few tinned goods, and some villages hold weekly markets where women sell or exchange garden produce and tapa.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025