Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

MOTU

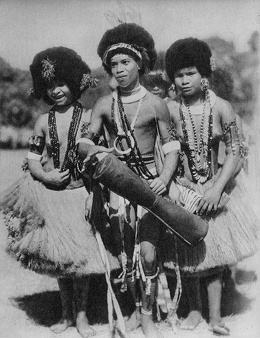

Motu in ceremonial clothes at the Hiri Festival Papua New Guinea Travel

The Motu are an Austronesian-speaking group that lives along the southern coastal areas of Papua New Guinea, They and the Koitabu people are the original inhabitants and owners of the land on which Port Moresby — the capital of Papua New Guinea — is located. The largest Motu village is Hanuabada, northwest of Port Moresby. Despite increased Westernization, the Motu people still engage in some traditional practices. These include valuing traditional music and dance, observing bridewealth, and retaining most land rights in the Port Moresby region. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Wikipedia]

The Motu (pronounced MOH-too) occupy a stretch of coastline that became the first area of permanent European settlement on the island of New Guinea. They figure prominently in the ethnographic record, largely because of their elaborate annual trading voyages across the Gulf of Papua. Their homeland lies in Papua New Guinea’s Central Province, with Port Moresby—built on land traditionally belonging to both the Motu and the Koitabu—now dividing their territory in half.

From April to November, the southeast trade winds make the Motu coast hot and dry; from November to March, the northwest monsoon brings rain and humid conditions. Behind and between the coastal villages are low hills, slopes, swamps, and valleys where the Motu traditionally maintained gardens and occasionally hunted. This hinterland was once covered in sparse tropical savanna dominated by dry grass and stunted eucalypts. Along the barrier reef, on inshore beaches, and in the lagoon waters, Motu communities fished. Today, some Motu live in small settlements on the outskirts of Port Moresby, while others reside in modern urban homes with electricity and running water.

According to the Christian research group Joshua Project, the Motu population in the 2020s was around 65,000. At first European contact, early missionary observations suggest the combined population of Motu villages—including small Koita minorities—was between 4,000 and 5,000. Numbers fluctuated during the early colonial period, but grew modestly overall. After World War II, rapid urbanization, wage labor, and improved medical services led to dramatic population growth. Records from 1954–1968 show an increase in the fourteen Motu villages from about 7,500 to 13,500. Although precise village-level figures are no longer available, the Motu population has continued to grow and may now exceed 25,000. Because of their proximity to Port Moresby, the Motu have played a historically significant role in the development of Papua New Guinea disproportionate to their size.

Languages spoke by the Motu include Motu (Hiri Motu), Tok Pisin, and English. Their indigenous language, Motu, is an Austronesian language in the Central Family, Eastern Subgroup, and is related to other Austronesian languages of coastal New Guinea and the broader South Pacific. Austronesian languages are a minority in Papua New Guinea and are mostly confined to coastal regions, reflecting later prehistoric migrations. Papuan languages dominate the inland areas. During their long-distance trading voyages, the Motu used a specialized form of their language known today as Hiri Motu. Recognizing its regional importance, the government made Hiri Motu one of Papua New Guinea’s three official languages, though it has since lost ground to Tok Pisin.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GEBUSI, PURARI, OROKOLO ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MEKEO, MAILU, WAMIRA ioa. factsanddetails.com

OROKAIVA AND MAISIN PEOPLE OF ORO PROVINCE IN SOUTHEAST PNG ioa.factsanddetails.com

FLY RIVER PEOPLES — GOGODALA, BOAZI, KIWAI — AND THEIR LIFE, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

KERAKI OF THE TRANS FLY REGION: LIFE, SOCIETY AND SODOMIST INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

KALULI (BOSAVI): HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

NINGERUM PEOPLE OF CENTRAL NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

Motu History

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Motu—skilled seafarers with a distinctive maritime culture and ceramic tradition—settled their present coastal homeland relatively recently in the long history of occupation along New Guinea’s southern shores. Motu men built large sailing craft known as lagatoi, multihulled rafts made from massive logs lashed together and powered by crab-claw–shaped sails woven from coconut fiber. Each vessel required a crew of roughly thirty men. Although the great hiri trading voyages are no longer undertaken, the Motu continue to commemorate them through annual ceremonies and cultural events. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Wikipedia]

When Westerners first recorded contact in 1872, the Motu—an Austronesian-speaking people—lived in thirteen compact seaside villages along the south coast, immediately east and west of Port Moresby, the earliest center of European settlement. A fourteenth village was founded shortly afterward. Three villages—Elevala, Tanobada, and Hanuabada—stood together along the Port Moresby harbor shore, just west of the modern city’s docks and commercial district. The Motu shared this coastline with the non-Austronesian-speaking Koita, who maintained their own hinterland villages but also lived in small enclaves within several Motu settlements.

Oral traditions and early accounts suggest that the Motu engaged periodically in warfare or raiding against neighboring groups and, at times, even against other Motu villages. Such hostilities, once endemic throughout the region, were eventually curtailed after the establishment of British colonial administration in 1884. The Motu still inhabit the same fourteen coastal villages today, although many have moved into suburban areas surrounding Port Moresby. Traditionally, most of their villages were built over tidal shallows, facing a barrier reef that lay some distance offshore.

The Motu attracted early ethnographic interest, and by the late nineteenth century were the subject of some of the first regional studies. Early European observers consistently described the same fourteen villages still occupied today. In 1896, Friedrich Ratzel noted that Motu tattooing resembled designs found in Micronesia and reported a mourning practice among older women of darkening the skin with a glossy black earth pigment. Charles Gabriel Seligman, working among the Motu in 1904, observed that they did not practice exogamy, though intermarriage with the inland Koitabu was common. The annual hiri voyages were central to Motu life; women produced pottery that was traded across the Gulf of Papua. In the 1920s, American artist Caroline Mytinger visited Motu communities and painted portraits, including scenes from Hanuabada.

From the arrival of Christian missionaries in 1872 and throughout the colonial period that began in 1884, the Motu—particularly those around Port Moresby—played an active role in the social, political, and economic transformations that eventually led to Papua New Guinea’s independence in 1975. Early colonial administration relied on Motu speakers, including Solomon Islands policemen who learned a simplified form of the language while stationed in Port Moresby. This simplified speech, first called “Police Motu” and now known as Hiri Motu, spread widely and became an important lingua franca in Papua. Educated Motu from Port Moresby villages also entered clerical and commercial positions, though before World War II only a minority of Motu earned wages; most still depended on traditional subsistence activities.

After World War II, increasing road access and urban employment opportunities drew Motu from both nearby and distant villages into the workforce of Port Moresby’s expanding commercial and service economy. Today, nearly all Motu men—and many women—hold full-time wage jobs. Those from nearby villages often commute daily, while others live in town during the week and return home on weekends. As the Motu became embedded in the urban labor force, traditional economic activities gradually diminished and eventually disappeared, aside from a few modern commercial fishing operations. Historically, the Motu maintained peaceful trading relationships with some neighboring inland communities, exchanging fish for vegetables and fruit. Their long-distance hiri voyages brought them westward to the Erema and Toaripi peoples of the Gulf of Papua, with whom they exchanged pottery and ornaments for sago, canoe hulls, and areca nuts. Outside of these alliances, contacts with other groups before colonization were generally sporadic and hostile.

The Motu have undergone more intense modernization than many other Papua New Guinean groups, and numerous traditional practices have faded. Most of the customary life-stage rituals once central to Motu society have disappeared, with the bride-price remaining as the sole traditional rite of passage still widely observed. Transitions from childhood to adulthood, and later to old age and death, now follow patterns influenced by European customs; Motu families in Port Moresby celebrate birthdays, and traditional mortuary rites are no longer practiced, although a mourning period of roughly four weeks is still observed for nonessential activities.

Motu Religion

The Motu were the first people on mainland Papua New Guinea to encounter Christian missionaries. According to the Christian research group Joshua Project, about 87 percent of Motu today identify as Christian, many as regular churchgoers, with 10 to 50 percent estimated to be Evangelicals. Missionary work in Motu territory was long dominated by the London Missionary Society, whose successor, the United Church, has significantly reshaped Motu religious life. Although some traditional beliefs and rituals persist, many older practices have been transformed or abandoned. For example, the Motu traditionally believed in the existence of witchcraft and sorcery but did not practice it themselves; instead, they thought such powers were held by neighboring groups and could be hired when needed. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditionally, the Motu believed that their well-being depended on the protection and favor of ancestral spirits. After death, these spirits were thought to travel westward across the sea to a land of abundance, while still maintaining concern for their living descendants. Households and iduhu (extended kin groups) conducted ancestral rites to promote success in gardening, fishing, and the hiri voyages. Ancestors were believed to watch over their descendants and punish wrongdoing with illness or misfortune.

Motu religion had few specialist practitioners. The only recognized experts were diviners, who identified certain illnesses or calamities as either ancestral punishment or the result of sorcery (mea) or witchcraft (vada). While the Motu believed that such powers were generally wielded by the Koita and other neighboring groups, individuals could hire these outsiders if they wished to use such forces.

Today, Motu communities celebrate major Christian holidays, as well as secular national holidays, reflecting their participation in Papua New Guinea’s wage-earning urban economy. The Hiri Festival is a particularly important annual event, allowing Motu people to honor their maritime heritage and display traditional dress, dance, and craft. In the past, ancestral support was sought through private household ceremonies at sacred places (irutahuna) associated with houses or canoes. Following the death of an important family member, a sequence of public rites unfolded over several years, culminating in a large feast with dancing (turia), during which the deceased’s bones were exhumed to ensure a successful passage into the ancestral realm.

Motu Family and Men and Women

The nuclear family is the core unit of social organization among the Motu. Traditionally, several households were connected by shared walkways and a communal cooking area. While food was pooled and prepared together, each nuclear family ate separately. Households—or, in some cases, individual nuclear families—maintained their own garden plots. Each household owned small fishing nets, whereas the larger nets were held and used collectively by the iduhu (the wider residential group). Houses and major household possessions were typically inherited by the eldest son. Although younger sons and their families might continue living in the same house for a time, they were expected eventually to establish their own separate households. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Marriage today differ significantly from marriage observed at first European contact. Modern Motu marriages are monogamous, whereas in precolonial times men of high status or wealth could have multiple wives. Marriages were traditionally arranged and subject to many restrictions, with child betrothal common. A series of gift exchanges accompanied the process, culminating in the final bride-price payment that formalized the union. Motu today are free to choose their partners, but rising wealth has driven up bride prices to some of the highest in Papua New Guinea—often exceeding 60,000 kina—which can delay the completion of marriage transactions.

Traditional norms also discouraged marriage with close cognates, though marriage within the village was preferred. This sometimes limited the number of eligible partners and encouraged flexibility in applying the rule to distant relatives. Gift exchanges formerly centered on arm shells, but today they include large sums of money. Bride-wealth inflation in recent decades, often led by wealthier Motu families, has increasingly slowed the final formalization of marriages.

Residence after marriage was traditionally viripatrilocal, with wives moving into their husband’s household or community. All members of the household helped raise children, though mothers carried most of the daily responsibilities. Boys learned practical and ceremonial skills from their fathers and senior men, while girls were instructed by their mothers and older women. Divorce was possible—requiring the return of bride-wealth—but was uncommon.

As a coastal society, the Motu do not display the strong sexual antagonism or segregation characteristic of many Highlands cultures. Men and women had clearly defined but complementary roles in the hiri trading expeditions. Women produced the pottery that men later exchanged for sago and other goods. While the men were away on these long voyages, unmarried girls remained secluded in their homes. During this period, they continued receiving elaborate tattoos and were taught proper female behavior and duties by senior women. During seclusion they were not allowed to bathe or comb their hair, and they ate only vegetables using special chopstick-like utensils called diniga.

Traditional Motu education was divided by gender: boys learned male tasks from male relatives, and girls learned female tasks from female relatives. Today, public schooling is widely available, and most families take part. Some Motu continue on to higher education at national institutions, such as the University of Papua New Guinea in Port Moresby.

Motu Society and Political Organization

Two major corporate groups structure social life in a Motu village: the household, made up of one or more nuclear families, and the iduhu, a cluster of households occupying a defined residential section of the village. Nuclear families within a household, and households within an iduhu, are usually connected through patrilineal ties—links between fathers, sons, and brothers at the household level, and between descendants of the founding ancestor at the iduhu level. Some rights, such as access to an iduhu’s communal fishing catch, extend to sisters and their children, while others—such as land rights—are shared more broadly among bilateral descendants. Nonetheless, the core membership of an iduhu, with the strongest claims to its resources and rituals, consists of patrilineal relatives. Although women marry out, they maintain close ties to their fathers and brothers. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Relations between Motu villages include acknowledged historical connections, but traditionally each village was politically independent, with no overarching authority above the village level. Leadership within an iduhu typically fell to its senior married male patrilineal relative, who also headed his household. Status among other men was based on genealogical seniority. Villages had no formal hierarchy, but influential men—usually iduhu leaders—competed for prestige by sponsoring major undertakings such as hiri voyages, feasts with dancing, large bride-wealth contributions, and, in precolonial times, demonstrating military prowess. In the contemporary cash economy, successful Motu men continue to pursue influence and public standing through bride-wealth payments, hospitality, and other forms of conspicuous expenditure.

Kinship Terminology follows the Hawaiian type, in which all female relatives of the parental generation—mothers as well as maternal and paternal aunts—are referred to by the same term. However, Motu do distinguish between relatives on the mother’s side and those on the father’s side.

Land Tenure is based on descent from the original cultivator or occupant. In principle, all descendants—male or female—hold rights to use or transfer a piece of land. In practice, traditional residential and garden rights were exercised mainly by patrilineal descendants, since men and their families remained within the iduhu and cultivated their fathers’ land, while women relocated upon marriage. During the colonial and postcolonial periods, when land began to be sold for cash, all descendants of the original occupant shared in the proceeds.

Political decisions within the village were traditionally reached through public debate. Leaders, or “big-men,” used persuasive rhetoric grounded in their achievements and prestige to shame rivals into withdrawing, allowing a victor or consensus to emerge. In the post-independence era, political decisions affecting the Motu are made through formal democratic mechanisms; Motu politicians build on local support and negotiate alliances within political parties and governmental institutions at local, regional, and national levels.

Conflict and competition were long-standing and integral aspects of traditional Motu life. Public rivalry in political debate motivated individuals and groups to strive for achievement. Victories were often temporary, and defeats seldom final; disputes could be settled by consensus, confrontation, or by gifts offered to appease the momentary winner, yet most disagreements simply paused until the next contest. Within the iduhu, social order was maintained through patrilineal authority reinforced by ancestral ritual sanctions.

Motu Villages, Houses and Urbanization

Motu villages were once tightly clustered, with houses built in rows over the water and linked by wooden walkways above the tidal flats. Each line of houses corresponded to a descent group—people tracing their origins to a shared ancestor. While many Motu still live in these over-water settlements, increasing numbers now build houses onshore. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Village houses today often feature corrugated metal walls, thatched roofs, and plank floors. In more traditional communities, electricity may be absent, so people rely on kerosene lanterns and battery-powered radios for lighting and communication. Urban Motu households vary widely, ranging from modest dwellings to large, fully modern homes owned by professionals.

Before European contact, travel between Motu villages was done mainly by canoe, and sometimes on foot. Today, all Motu settlements are connected to Port Moresby by road, though canoes remain in regular use. The Motu are especially well known for the large ceremonial canoes used in their historic hiri trading voyages.

The Motu Koitabu are the Indigenous people of the Port Moresby region, numbering about 30,000. They are the traditional landowners of what is now the National Capital District. Since Papua New Guinea’s independence in 1975 and the city’s rapid expansion, Motu Koitabu political, economic, social, and cultural life has been increasingly marginalized. In response, community leaders held the Inaugural Summit on Motu Koitabu in Baruni village in 1999, producing the “Baruni Declaration,” which outlines agreed-upon priorities for social, economic, and environmental reform. Issues such as garbage accumulation and pollution in Port Moresby and its surrounding villages now pose serious challenges for Motu Koitabu communities.

Motu Life

Because many Motu now live and work in Port Moresby, their greetings and farewells follow urban social norms. The most meaningful part of these interactions is the choice of language. Motu typically greet one another in Hiri Motu, but they may also use English or Tok Pisin. The language selected signals the nature and closeness of the relationship between the speakers. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditionally, Motu labor was divided by gender. Men built houses and canoes, made fishing nets, fished, and took part in long-distance trading voyages. Women produced the pottery traded on hiri expeditions, prepared food, fetched water, and gathered a wide range of marine and terrestrial resources. Both men and women worked in the gardens, where only limited crops could be grown. Today, Motu men and women alike pursue wage labor—usually in nearby Port Moresby—and many hold professional, white-collar positions. Most traditional crafts have largely disappeared, surviving mainly as demonstrations revived during festivals and ceremonies.

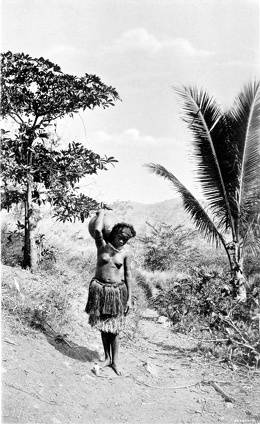

Clothing for Motu women traditionally was skirts made of grass fiber, with no footwear and no upper-body covering. Their torsos were often tattooed. On ceremonial occasions, both men and women oiled their skin and adorned themselves with feathers, flowers, and croton leaves, which were also tucked into armbands. Traditional attire continues to be worn for events such as bride-price ceremonies, weddings, and canoe races, while urban Motu dress entirely in Western clothing.

Traditional Foods were fish, yams, bananas, and gathered shellfish and crabs. The Motu also traded locally and through long-distance voyages for additional foods. In some western Motu communities, a thriving tuna-fishing industry persists, tied to an important origin myth. Today, imported foods have become staples: tinned fish, canned Indonesian curries, rice, and tea are common, and Port Moresby shops stock American items like boxed cereals, soft drinks, and hot dogs. Although food is often pooled and prepared communally, individual nuclear families typically eat separately.

Preserving cultural identity in the rapidly modernizing environment of Port Moresby is one of the Motu’s greatest challenges. Their language is losing ground to Tok Pisin among younger generations, especially those growing up in the city and its expanding suburbs. Broader national issues—alcohol and drug abuse, the spread of HIV, and enforcement of laws restricting ammunition and pornography—also affect Motu communities. The ban on pornography is partly intended to protect respect for women’s traditional attire. During the Miss Papua New Guinea pageant, contestants are required to wear traditional dress, which for many involves appearing topless. Both the government and society emphasize preserving the cultural significance of this clothing and preventing its objectification.

Motu Culture

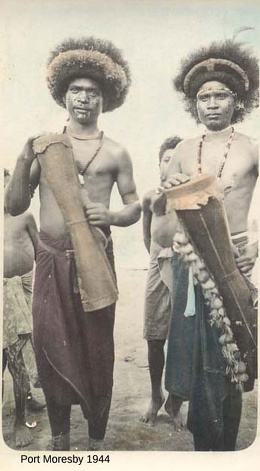

Traditional Motu dances were striking spectacles. Dancers—both men and women—wore elaborate face paint and feathered headdresses and performed large, synchronized routines accompanied by drumming and occasional singing. The drum most commonly used was the kundu, a hand-held hourglass drum found throughout Papua New Guinea. Christian missionaries discouraged dancing, and as a result many ceremonial performances disappeared and survive only in memory. Some dances are still presented on major occasions and for visiting tourists. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Urbanization and formal education have also contributed to the rapid decline of Motu folklore and mythology. Many children today no longer hear the traditional stories that once passed from generation to generation. Among the tales that remain, older Motu still recall accounts of conflicts with neighboring groups, including ancestral raids. Myths about Motu origins, the discovery of fire, and the history of the hiri trading expeditions have been written down and published in small booklets. Many other Papua New Guinean communities have taken similar steps to preserve their traditions, even if in altered form.

Rugby is a major sport throughout Papua New Guinea, enjoyed both as a spectator and as a participant activity; Motu living and working in Port Moresby can easily attend league matches. Canoe racing—using vessels modeled on traditional designs but built from modern materials—remains a popular recreational activity. For those in the Port Moresby area, entertainment also includes movie theaters, clubs, and pubs. The national “Miss Papua New Guinea” beauty pageant is an important annual event in the capital, and Motu contestants are consistently well represented.

Art: Motu artistic traditions centered mainly on pottery made by women and the intricate tattoos traditionally worn by women. Pottery—cooking pots, water jars, and platters—was functional and elegantly shaped but minimally decorated. The most spectacular artistic expressions appeared in dance regalia: feather headdresses, vivid face paint, arm shells, plaited amulets, women’s grass skirts, and men’s perineal bands, all set in motion to the rhythms of wooden drums. Early missionaries condemned dancing as morally dangerous and banned it. For generations, Motu society was divided between Christians, who avoided dancing, and “pagans,” who continued it. Although Christian norms eventually prevailed, some dance forms survive today as cultural presentations for tourists or historical celebrations.

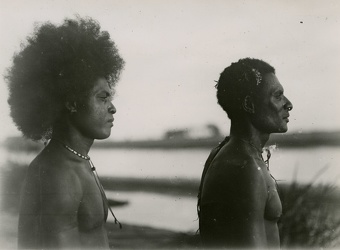

Tattooing of Motu women was a notable tradition. While men were tattooed only across the chest to mark success in headhunting raids, women were tattooed extensively, from head to toe. Designs were passed from mothers to daughters, and the process began early: girls received their first tattoos on the backs of their hands around age five, with additional patterns added at specific ages until a young woman was fully tattooed by the time she married after puberty. Today, many girls reproduce the designs with felt markers rather than enduring the painful and permanent traditional method, though some continue to receive real tattoos. Motu tattoo patterns are geometric, and in recent times some Christian motifs have been incorporated into the designs.

Motu Agriculture and Economic Activity

Traditionally, the Motu cultivated yams and bananas, along with a few minor crops, in garden plots scattered along the shoreline and across nearby hills. They also maintained clusters of coconut palms near their villages, kept pigs mainly for ceremonial purposes, fished extensively, and collected shellfish and crabs. These activities, however, did not produce enough staple food to meet their needs, so the Motu supplemented their supplies through trade—exchanging fish, pottery, and ceremonial ornaments with neighboring groups and with partners reached through overseas trading voyages. [Source: Murray Groves, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The Motu had no craft specialists in the traditional sense; the only clear division of labor was by gender. Men fished, built canoes and houses, made fishing nets, and took part in the hiri trading expeditions. Women gathered shellfish and crabs, made pottery, cooked, and fetched water. Garden work was shared: men initially broke the soil, women weeded and cleared it, and both sexes planted, tended, and harvested crops together.

Most trade took the form of reciprocal gift exchange, though direct barter also played a role during the hiri voyages. Ceremonial exchanges involving valuables—such as arm shells, ornaments, pigs, and yams—took place between individuals and groups from different villages or iduhu at feasts with dancing, often linked to mortuary rites, and between kin and in-laws during marriage transactions. With the exception of a few commercial fishermen, the Motu have made little effort to market traditional goods or develop new cash crops.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025