Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

SOUTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA:

The Southern Region is one of four regions of Papua New Guinea. It includes the national capital Port Moresby and is administratively divided into six provinces: 1) Central, 2) Gulf, 3) Milne Bay, 4) Oro (Northern), 5) Western (Fly River) and 6) National Capital District (Port Moresby). The Southern Region of Papua New Guinea is dominated by southwestern lowlands, which form the largest contiguous lowland area in the country and home home to the Southeastern Papuan rain forests, Southern New Guinea freshwater swamp forests and Southern New Guinea lowland rain forests. There are large rivers, deltas and swamps. The Fly River, which is 1,050 kilometers (650 miles) in length, flows through one of the largest swamplands in the world to the south coast.

Western Province lies along Papua New Guinea’s southwestern coast, bordering Indonesia’s Highland Papua and South Papua provinces. Its capital is Daru. Tabubil is the largest town. Other important centers include Kiunga, Ningerum, Olsobip, and Balimo. Covering 99,300 square kilometers (33,840 square miles), Western Province is Papua New Guinea’s largest province. The Fly River and its major tributaries—the Strickland and Ok Tedi—cross the region, and Lake Murray, the country’s largest lake, is also located here. In the 2011 census the province had 201,351 people in 31,322 households, with an average household size of 6.4. Population distribution was: Middle Fly (79,349), North Fly (62,850), and South Fly (59,152). [Source: Wikipedia]

Gulf Province occupies Papua New Guinea’s southern coast, with Kerema as its capital. Its 34,472 square kilometers (13,310 square miles) landscape consists of mountains, river deltas, and wide floodplains. The Kikori, Turama, Purari, and Vailala Rivers all drain into the Papuan Gulf. With 106,898 residents (2000 census), it has the country’s second-smallest population. It borders Western Province to the west; Southern Highlands, Chimbu, and Eastern Highlands to the north; Morobe to the east; and Central Province to the southeast.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOTU — THE PORT MORESBY AREA PEOPLE — AND THEIR HISTORY, CULTURE, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MEKEO, MAILU, WAMIRA ioa. factsanddetails.com

OROKAIVA AND MAISIN PEOPLE OF ORO PROVINCE IN SOUTHEAST PNG ioa.factsanddetails.com

FLY RIVER PEOPLES — GOGODALA, BOAZI, KIWAI — AND THEIR LIFE, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

KERAKI OF THE TRANS FLY REGION: LIFE, SOCIETY AND SODOMIST INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

KALULI (BOSAVI): HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

NINGERUM PEOPLE OF CENTRAL NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

Gebusi

The Gebusi are an ethnic group that lives in the lowland rainforests of the East Strickland River Plain of the Western Province in Papua New Guinea near the Nomad River. Also known as the Gobasi, Bibo and Nomad River peoples, the Gebusi traditionally lived in longhouse communities, practiced a mix of foraging and horticulture, and engaged in practices such as sorcery, ritual violence, and distinctive sexual customs. A central cultural ideal was kogwayay—“good company”—which emphasized sociability and harmony even as sorcery accusations contributed to a high rate of homicide. The Gebusi see themselves as sharing cultural affinities with neighboring Nomad River peoples, including the Honibo and Samo, and, to a lesser extent, the Bedamini to the east. Although they had sporadic contact with outsiders beginning in 1959, they remained isolated for decades, lacking roads and basic infrastructure. From the late 1990s onward, many Gebusi converted to Christianity, entered the cash and market economy, attended government-run schools, and began participating in regional sports. [Source: Bruce Knauft, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Google AI]

The Gebusi inhabit a hot, humid, tropical rainforest environment with very high rainfall. Their traditional territory is bounded by the Hamam River to the north, the Nomad River and Nomad government station to the northwest, and the Rentoul River to the south. The landscape consists largely of relict alluvial plains cut by erosion into parallel ridges and valleys rising up to 75 meters, giving an illusion of flatness from the air despite an elevation reaching 200 meters above sea level. Soils are heavy clay with stones found only in major riverbeds. Primary rainforest covers nearly all the area except for garden clearings and riverbanks. Median monthly high temperatures range from 32.5°C to 38°C (90.5̊F to 100.4̊ F), with extremes reaching 42°C. (108̊F), Annual rainfall averages 416.5 centimeters (164 inches) with a variable dry season from June to early November; humidity remains consistently high.

In the 2020s, the Christian research group Joshua Project estimated the Gebusi population at around 2,800. In 1980–82, their population was roughly 450, at a density of 2.6 people per square kilometer. The Gebusi experienced significant depopulation due to epidemic influenza, tuberculosis, and other respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases, resulting in a natural population decline of about 24 percent between 1967 and 1982. This loss was offset by immigration—mainly from Bedamini groups to the east—leading to a small net increase of about 1.3 people per year within Gebusi territory during that period.

Language” The Gebusi speak Gobasi — a language in the East Strickland language family within the South-Central New Guinea stock of the Trans–New Guinea phylum. Variants include Oibae, Bibo, and Honibo. The Gebusi language forms part of a dialect chain extending from the Strickland River east to Mount Bosavi and Mount Sisa. A partial break in this chain occurs between the Gebusi and the Bedamini, who share only about 32 percent of cognates — a reflection of past Bedamini expansion into formerly intermediate linguistic territories.

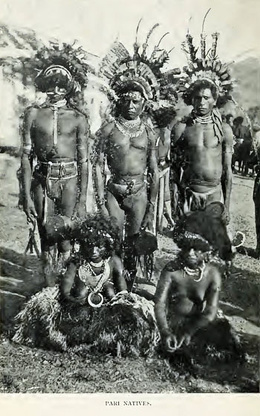

History: The Gebusi are among roughly a dozen cultural and linguistic groups in the Strickland–Bosavi region, each with its own language and distinct customs. Shared features across the area include: residence in communal longhouses where men and women sleep in separate sections; social organization based on small, dispersed patriclans linked through agnatic, affinal, and matrilateral ties; all-night spirit-medium seances addressing illness, curing, sorcery, and conflict; collective subsistence; a single-stage initiation into adult manhood; and inter-longhouse dance and songfest rituals featuring elaborately costumed dancers accompanied by plaintive singing. Intergroup raiding was common, and the Gebusi were frequently targeted by the more populous Bedamini to the north and east, who pushed into border zones.

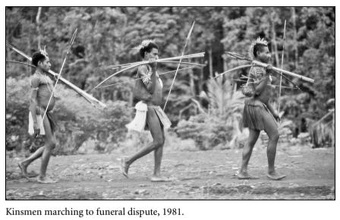

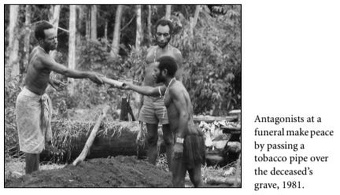

Warfare between Gebusi settlements was uncommon, especially compared with the organized raids conducted by the Bedamini. Ritualized fights between Gebusi communities could escalate into club-wielding clashes but rarely advanced to bow-and-arrow combat, and casualties were infrequent. Fights could also arise over unreciprocated marriages or accusations of adultery, but these too seldom led to serious injury. The most intense form of social conflict stemmed from sorcery accusations. Unlike many New Guinea groups, the Gebusi frequently made public accusations, subjected suspects to demanding divinatory ordeals, and carried out executions. From roughly 1940 to 1982, 29 percent of female deaths and 35 percent of male deaths were homicides, nearly all linked to sorcery attributions. This corresponds to an estimated annual homicide rate of at least 568 per 100,000 adults over 42 years. Yet no evidence indicates that actual sorcery packets are produced or used; sorcery among the Gebusi is a projective accusation of deviance. Most older individuals eventually face such charges. The appearance of impartiality in spiritual inquests helps secure consensus—including among diverse clan members—to execute accused individuals without provoking retaliation from their kin. Statistically, sorcery-related killings occur most frequently between affines connected through nonreciprocal marriages, with wife givers and wife receivers targeted at similar rates.

Government patrols pacified the Bedamini in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Gebusi themselves were first effectively contacted in 1962 and remained relatively isolated thereafter, interacting mainly with annual government patrols, a mission station established in the mid-1980s, and occasional geological survey crews working near Nomad. As late as 1980–82, spirit seances, sorcery investigations, male initiation rites, and ritual homosexuality were still practiced.

Gebusi Religion

According to the Christian-oriented Joshua Project, about 90 percent of Gebusi today identify as Christians—primarily Protestants—with an estimated 10 to 50 percent being Evangelical. Traditional Gebusi religion once placed strong emphasis on sorcery and shamanic practice, but these beliefs have largely been reshaped within a Christian framework in which God is regarded as the ultimate force confronting evil. [Source: Bruce Knauft, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

In their traditional cosmology, the Gebusi recognize a spirit world filled with beings associated with fish, birds, and other animals. Especially important are the “true spirit people” (to di os), who help reveal the causes of illness, identify sorcerers, locate lost pigs, and ensure successful hunts. Although spirits may cause temporary ailments, nearly all human deaths were traditionally attributed to other Gebusi through sorcery or homicide. Sorcery was also believed to predispose people to accidents and suicide. After being accused by spirits, suspected sorcerers were required to undertake corpse or sago divinations, though these rarely proved effective in clearing their names.

Religious Practitioners: Male spirit mediums communicate with spirit beings during all-night séances held roughly every eleven days. Sitting quietly in a darkened longhouse, the medium enters a trance in which his spirit departs and is replaced by beautiful spirit women who chant in high falsetto. A chorus of men echoes their songs line by line. During these séances, the spirits perform healing rituals and deliver authoritative pronouncements about sorcery. Mediums themselves have no special personal authority beyond what is conveyed through the spirits, and they receive no payment for their services, which are viewed as a civic responsibility.

Ceremonies: The benevolent harmony of the spirit world is celebrated in an all-night dance performed at major feasts and important gatherings. Male dancers wear elaborate, highly standardized costumes that visually unite spirits of the upper and lower worlds. These ceremonies also serve a social function, helping to repair tensions between hosts and visitors through feasting, kava drinking, dancing, and ribald male camaraderie. Male homosexual relations sometimes occur privately during these events. Gebusi traditionally believe that boys must be orally inseminated to gain male life force and mature into adulthood; this continues through adolescence and culminates in the initiation rite wa kawala (“child becomes big”) between ages 17 and 23. Initiation is largely benevolent: novices receive gifts and costume pieces from sponsors and reciprocate with food offerings. The initiates are eventually dressed in red bird-of-paradise—or “spirit woman”—costumes and honored during several days of communal celebration.

Death and Afterlife: When divination confirms a sorcery accusation, the suspect’s execution and cannibalism traditionally followed, after which the person’s spirit was believed to reincarnate as a dangerous wild pig. Until recently, those killed as sorcerers were butchered, cooked with sago and greens, and eaten by the community—except for close relatives and patrilineal kin, who were excluded. Individuals who died from sickness or accidents were not cannibalized; instead, their spirits were thought to reincarnate as birds, animals, or fish appropriate to their age and sex. Such deaths were marked by a funeral feast.

Gebusi Family, Marriage and Sex

A married couple has traditionally formed the basic Gebusi gardening unit, though many subsistence, foraging, and household tasks are carried out collectively by groups of men or by groups of women. The effective domestic unit usually consists of two or three closely related nuclear families linked through agnatic, affinal, or matrilateral ties. Patterns of co-residence reflect these relations: in the 1980s and 90s adult male wife’s brothers/sisters’ husbands co-resided at 68 percent of the rate possible; mother’s brothers/sisters’ sons at 82 percent; father’s brothers’ sons at 85 percent; wife’s father/daughter’s husbands at 88 percent; and brothers at 92 percent. The settlement as a whole is made up of several interconnected extended-family clusters and functions as a unified domestic group for sponsoring feasts. [Source: Bruce Knauft “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Marriage ideally follows a sister-exchange system, and such same-generation exchanges between clans account for about 52 percent of first marriages. However, a competing ideal of unreciprocated romantic marriage is also strong. In either case, neither bridewealth nor bride-service is involved. Divorce and polygyny are relatively uncommon: 14 percent of completed marriages end in divorce, and 7 percent of married men had more than one wife in the 1980s and 90s. Polygyny most often arises through the levirate, as the small patriline or subclan holds primary rights to the widows of its deceased men and is likewise responsible for providing “sisters” in exchange for the wives of its male members. Postmarital residence may be uxorilocal/matrilocal, neolocal, or virilocal/patrilocal, with a general tendency toward virilocal residence.

Child socialization is characteristically gentle and nurturing. Both fathers and mothers indulge young children; older children are rarely scolded and almost never struck. Boys move gradually and without coercion to the men’s sleeping area of the longhouse between ages 4 and 7. Male initiation—occurring between ages 17 and 23—is celebratory in tone and marks a positive, nontraumatic transition into adulthood.

The Gebusi’s initiation for boy traditionally included homosexual acts and male insemination. The practice had largelt been stopped by the 1990s. In contrast to the “Sambia”, Gebusi did not say or imply that men had to be inseminated to reach adulthood; “this was simply an erotic act that could help them in this regard”. Bruce Knauft wrote in 2003: “Avid and openly pursued sexual relations between prospective initiates, who were generally between about 16 and 20 years of age. In addition to being inseminated by fully adult men, these novices, during the months prior to their initiation, joked bawdily with each other, engaged in ribald sexual horseplay, and sometimes paired up and brought each other reciprocally to orgasm, to the amusement and heightened joking of other men. Like the trysts between novices and adult men, these sexual engagements occurred privately and dyadically at night in the bush just outside the longhouse during the course of all-night spirit seances or ritual dances-that is, in a general context of ritually vaunted male ribaldry. The stereotypic nature of these events and their association with spiritual celebration suggested, at least for Gebusi MSM, that "ritualized homosexuality" was, at least in relative terms, a better term than "boy insemination.” [Source: “Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin, August 2005; [Source: Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

Gebusi Society

Gebusi social and political life is highly decentralized. There are no formal leaders—no big-men, headmen, senior elders, or war chiefs—and adult men tend to be egalitarian, uncompetitive, and self-effacing. Collective decisions arise through consensus. Despite the range of clan affiliations among co-resident men, the settlement functions as the primary political unit for hosting feasts and engaging in conflict. Full adult male status is achieved through a single-stage initiation and subsequent marriage. Little structural inequality exists between wife givers and wife takers; affines exchange food evenly regardless of the balance of marriage exchanges. Gift-giving and food-sharing reinforce relationships in a noncompetitive manner both within and between settlements. The Gebusi do not use bridewealth, bride-service, or homicide compensation, instead relying on direct reciprocity in marriage and, where deemed appropriate, in sorcery-related retribution. [Source: Bruce Knauft, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Gender relations form a major axis of sociopolitical organization. Men collectively control rituals, feasts, formal fighting, and large-scale cooperative activities. Women often participate as singers but dance only during initiations, are usually excluded from spirit séances, and can be beaten by husbands without community sanction. Women seclude themselves in their longhouse section during peak menstruation, and men express nominal beliefs about female sexual and menstrual pollution—ideas treated more as humorous banter than genuine anxiety. Despite these restrictions, many women exert meaningful influence in choosing spouses, even within the expectations of sister exchange, and day-to-day marital relations are generally harmonious. Male attitudes toward women are ambivalent: women are viewed positively as sexual partners and helpers—an image embodied in the benevolent spirit-woman figure—yet older women may be disparaged for their perceived diminished sexual, productive, and reproductive roles.

Kinship: The only named, enduring kin group among the Gebusi is the patriclan, which can range from a single member to as many as sixty-seven, with an average size of about eighteen. Clans acknowledge nominal “sibling” relationships with a small number of other clans, based on claims of shared residence in the past. Genealogies are very shallow: patrilineal links are rarely traceable beyond first or second cousins. Although clans are theoretically unified groups, they are usually scattered across the landscape, and the subclans and patrilines within them operate with near-total autonomy, even when they contain only one to three adult men.

Kinship Terminology used by the Gebusi is bifurcate-merging system with Omaha-style generational merging. This means certain relatives—such as mother and mother’s brother’s daughter, or child and sister’s child—are classified under the same terms. Affinal ties extend from the whole wife-giving clan to the groom. In line with Omaha patterns, relatives are distinguished by both descent and gender: a father and his brothers share one term, as do a mother and her sisters, while their opposite-sex siblings are labeled with separate “aunt” and “uncle” terms. Parallel cousins (children of same-sex siblings) are treated as siblings, whereas cross-cousins (children of opposite-sex siblings) are distinguished as cousins.

Land Rights are nominally patrilineal, but in practice residence provides broad rights of use and access. Most Gebusi do not reside on or cultivate their fathers’ lands, though they may visit those areas to harvest sago palms, gather nuts, or exploit other foraging resources. Ideally, each patriclan possesses rights to clearly bounded tracts of land, yet members are often dispersed and may live outside these areas. Conversely, clans that have migrated into Gebusi territory—including refugee or intrusive groups—may lack ancestral land altogether but still become numerically or politically influential in their communities. Land rarely becomes a source of conflict, and there is no apparent scarcity. Aside from enduring resources such as sago palms or nut trees, there is little property to inherit. Material items—typically a pig or a pearl-shell fragment—are usually passed from father to son.

Gebusi Villages and Economic Life

From the air, Gebusi settlements appear as small clearings scattered across dense rainforest. In 1980–82, seventeen main residential sites existed, averaging about 26 people each, with populations ranging from 6 to 54. Although dispersed, smaller settlements gravitated socially toward larger ones, where initiations, major feasts, and dances were held. Larger communities featured a communal longhouse—over 20 meters long and roofed with sago leaves—with a central ground-level area for cooking and socializing and elevated, sex-segregated sleeping areas at the rear. These longhouses were complemented by small garden houses and temporary shelters used during extended gardening or foraging trips. Daily life was highly mobile: on any given night, about 45 percent of residents slept away from the village. [Source: Bruce Knauft, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Gebusi craftsmanship includes finely made initiation arrows, armbands, net bags, and elaborate dance and initiation costumes. Men hunt, fish, fell trees, build houses, and make weapons and ritual ornaments, while women process sago, carry garden produce and firewood, do most weeding and harvesting, and craft net bags, skirts, sago baskets, and bark cloth. Healing is largely spiritual rather than physical.

Subsistence blends small-scale gardening, sago processing, foraging, and fishing. Hunting is irregular, and pig husbandry is minimal. Bananas provide about 65–70 percent of dietary starch, sago contributes 25–30 percent, and root crops the remaining 5–10 percent. Gardens are typically unfenced and quickly cleared, dominated by banana plots. Protein comes mostly from opportunistic foraging—grubs, bird eggs, nuts, and river species. Despite this mixed diet, many children show signs of malnutrition, including distended abdomens and limited muscular development.

Crafts and everyday objects are modest but made with some skil: men craft bows and arrows, drums, tobacco pipes, palm-spathe bowls, ritual ornaments, and—after the arrival of steel tools—canoes. Women weave net bags, sago pouches, ritual chest bands, string skirts, and bark tapa. In the early 1980s, cash cropping, wage labor, and outmigration were rare, and no trade stores existed locally or at the Nomad station.

Indigenous trade was flexible and opportunistic, with no fixed exchange rates. Gebusi traded items such as tobacco and dogs’-teeth necklaces to neighboring groups in return for red ocher, cuscus-bone arrow tips, pearl-shell slivers, and—before colonization—stone axe heads sourced near the Strickland River.

Purari

The Purari live in the Purari River delta region of southern Papua New Guinea. Also known as the Koriki and Namau, they live in a swampy area characterized by waterways that serve as their main avenues for travel. They fish and cultivate sago, nipa palms, sweet potatoes, pineapples, and other vegetables. Historically, their culture included practices such as headhunting and the performance of elaborate rituals and funerals, some of which used bullroarers called "imunu viki" during funerals. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Purari delta is formed by the five mouths of the Purari River.The region is extremely wet and hot, dominated by mud, standing water, and scattered islands of firmer ground. Freshwater marshes support stands of sago and nipa palm, while nearer the coast, dense mangrove forests prevail. The waterways serve as the primary routes for travel and communication between settlements and provide an abundant supply of fish that is central to the local diet. “Namau” is a term used by neighboring peoples to refer both to the region and its inhabitants in the Purari River delta. though many local residents prefer to call themselves “Purari.”

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 11,000. In the 1990s, the number of Purari-language speakers was estimated to be around 6,500. The population declined during the early twentieth century but has grown slowly since the mid-1950s, partly due to improved access to Western health care. Within this broader population, several named tribes exist, including the Koriki, Tai, Kaimari, and Maipua. Language: The Purari language is classified as a linguistic isolate, unrelated to neighboring languages such as Northeast Kiwai to the west or Orokolo to the east.

History: Information about Purari history before European contact is limited. Oral traditions among the Kaimari and Maipua suggest possible migration into the region from the southwest, though other groups have no such narratives. Traditionally, the Purari had a reputation for warfare, and both headhunting and ceremonial cannibalism played important roles in ritual life—especially in male initiation. Before European contact, warfare between tribes was not uncommon, though it was very rare within the tribe. Conflicts could arise from accusations of sorcery, theft, or wife-stealing, and raids were often conducted against other Purari groups. Battles typically involved two opposing lines of warriors exchanging volleys of arrows, with efforts made to maintain roughly equal casualties on each side.

European contact began in 1894, followed by colonial administration, labor recruitment, missionary activity, and modernization initiatives. Many Purari men served in the Papuan Infantry Battalion during World War II, and their wartime experiences—combined with exposure to Western goods and ideas—fueled local dissatisfaction afterward. This unrest gave rise to the Tommy Kabu movement, an ambitious attempt to create a cooperative economy, dismantle older ceremonial systems, and assert regional political autonomy. Lacking government backing and sufficient trained personnel, however, the movement had little lasting success and had largely dissipated by 1955.

Purari Religion and Culture

According to the Joshua Project, about 99 percent of Purari today identify as Christian, with an estimated 10–50 percent identifying as Evangelical. Historically, however, Purari religion combined animism, ancestor veneration, and a rich ceremonial tradition. The core of traditional Purari belief was imunu, an all-pervading spiritual force comparable to mana in other parts of Oceania. Every being, object, and natural feature possessed its own form of imunu: river spirits were regarded as the mythic ancestors of river clans, and various animals and environmental features embodied their own spiritual powers. Ancestral ghosts, along with the spirits of slain warriors, were believed capable of troubling the living. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Religious Practitioners and Rituals: Ritual knowledge was restricted to men, and women were excluded from the esoteric teachings of a patrilineage’s river spirit or totem. Each ravi (patrilineage) had two or more hereditary priests who oversaw major ceremonies. Sorcerers—always assumed to be male—were feared for their ambition, antisocial behavior, and neglect of ritual obligations. Traditional ritual life included the use of bullroarers (imunu viki, “weeping spirits”) during funerals for prominent men. Large wickerwork masks and effigies were central to initiations, life-cycle ceremonies, and rituals linked to warfare and victory. Marriage, in contrast, involved no formal ceremony. Illness and misfortune were attributed to the actions of spirits, sometimes aided by sorcery. Healing focused on persuading or appeasing the offending spirit, typically through the work of a ritual specialist. Western medical care became available after 1949, when the London Missionary Society established a hospital; today each large Purari settlement has a clinic.

Death and Afterlife: In earlier times, mourners marked grief by covering themselves with mud and observing food taboos. The dead were wrapped in mats and left to decompose in their houses—later abandoned—while the bones were kept as relics or charms. Under missionary influence, burial became more common. A funeral feast gathered the entire tribe: the spirit of the deceased was believed to consume the essence of the food, leaving its physical form to be shared among mourners. The feast lifted mourning taboos, though the spirit was still thought to linger nearby and might return as a troublesome ghost.

Art: Purari artistic expression reached its height in woven masks. Two main types existed: large kanipu masks kept in the men’s house, and aiai masks made for specific ceremonies and burned afterward. A stylized face motif dominated mask design as well as carvings on bowls, spoons, canoe prows, and other objects. Additional decorative arts included carved bark belts, combs, drums, and pearl-shell breastplates. Bodily adornment featured nose and ear plugs, scarification, shaved or styled hair, and other forms of ornamentation.

Purari Family and Kinship

Traditionally, Purari marriages were polygynous. Cowives shared a single dwelling but maintained separate sections for themselves and their young children, where they ate and slept. Women managed their own gardens and cooked for their children. In recent decades, the nuclear family has become the primary residential and work unit. Young children are largely cared for and disciplined by their mothers. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Initiation rites guided children, especially boys, into adulthood. Around age 8, boys were taken upriver to join the totemic groups of their patrilineal clans. By age 13, boys of the same patrician underwent seclusion and ceremonial training in a specially built ravi, after which they assumed the status of warriors. Heritable property passed patrilineally: sons inherited shell ornaments, canoes, pigs, and dogs from their fathers, while daughters inherited their mothers’ tools and personal items.

Marriages were often arranged in childhood, though wife stealing occurred and could spark conflict. Bride-wealth was customary, and postmarital residence was patrilocal. Wife exchange was common, and divorce was generally unavailable to women. Husbands had legal authority over their wives, and relationships among cowives were frequently tense. By the 1950s, traditional marriage practices and their connections to the descent system had largely dissolved, giving individuals more freedom to choose partners and placing the nuclear family at the center of social life.

Kinship Purari society is patrilineal ((based on descent through the male line), with membership in several river clans named for local rivers and associated totems. These clans were traditionally exogamous (marrying outside the group) and organized into moieties (things with two parts). By 1955, the clan and moiety systems had largely lost social function, and Purari society shifted toward a kin-based system. Settlement and garden land, as well as waterways, are linked to local patrilineal groups rather than individuals, and land rights are inherited by all sons of a father’s group.

Kinship Terminology follows the Hawaiian, or generational, system. This simple classification distinguishes relatives only by generation and gender. In the parental generation, all females (mother, aunts, and wives of men in that generation) are called “Mother,” and all males (father, uncles, and husbands of women in that generation) are called “Father.” In the children’s generation, all brothers and male cousins are “Brother,” and all sisters and female cousins are “Sister.”

Purari Society, Life and Economic Activity

Traditional Purari society was structured around exogamous moieties, river clans, and localized patrilineages, guiding marriage and affinal relations. At the settlement level, the ravi united men from multiple patrilineal groups, though each group maintained its own ritual obligations and masks. Cooperation across lineages occurred for large projects like house building, warfare, and collection of bride-wealth. Villages and moieties each had a chief whose authority relied on physical strength, success in warfare, and raiding, but leadership required consent and generally did not extend beyond the hamlet. The Tommy Kabu movement attempted to unite Purari communities politically and economically, establishing temporary police, courts, and jails, but these were eventually replaced by provincial and national government systems. Traditional social control was based on totemic beliefs and taboos. Sorcery fears served as a check on antisocial behavior. Husbands could discipline wives for failing duties, and adulterous wives risked severe punishment.

Traditionally, Purari settlements, housing up to 2,500 people, were built on islands of drier land scattered throughout the swamps. Houses were elevated on stilts, with high front elevations reaching 20 meters, sloping to 4–5 meters at the rear, to protect against flooding. Men and women had separate dwellings, both internally partitioned. Women’s houses had individual alcoves for each woman and her young children, while the men’s house, or ravi, served as a ceremonial center. Alcoves in the ravi were assigned to small patrilineal groups of men and initiated youths, each with its own hearth. Modernization, including the Tommy Kabu movement, has introduced European-style houses and relocated settlements to drier areas; traditional men’s houses are no longer built. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Men’s work included cooperative house construction, canoe building, carving masks and effigies, hunting, tending gardens and coconuts, and sport fishing with bows and arrows or spears. Women fished more seriously using hand traps, nets, and stream nets, processed sago floated downriver by men, gathered crabs and other foods, and made baskets, skirts, and other utilitarian and ritual items. While all men were expected to be able to craft essential items, some became recognized specialists, particularly as carvers or boat builders.

The Purari diet relied on taro, sweet potatoes, sago, coconuts, and bananas, supplemented by fish, crabs, wild pigs, wallabies, birds, and grubs. Rattan, obtained on upriver expeditions, was essential for house building and ritual objects. After Western contact, Purari men worked for wages on European plantations. Purari crafts include building houses and canoes, making weapons and fishing gear, and creating ritual and ornamental objects from feathers, pearl shells, and rattan. Many items feature carved totemic designs. Canoes were primarily for local use but sometimes sold. Outside ceremonial exchanges, the only significant trade was with Motu canoes participating in the hiri trading system.

Orokolo

The Orokolo live in the Gulf Province of Papua New Guinea, between the mouths of the Vailala River (to the east) and the Aivei River (to the west). Also known as Elema, Ipi, Western Elema, They have traditionally lived along the beaches of the 20-mile-wide Orokolo Bay in the Gulf of Papua. Their territory consists of a broad coastal strip lined with coconut palms, beyond which stretch the sago swamps that supply much of their food. Although the region is tropical, it experiences an unusual reversal of New Guinea’s typical monsoon pattern. From October to April, the northwest monsoon brings a relatively dry, calm season, while the normally gentle southeast trade winds blow straight into the gulf for the rest of the year, producing heavy rains and rough surf. [Source: Richard Scaglion, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Orokola population in the 2020s was 49,000. In 1937, the ethnographic present for this report (when F. E. Williams completed his major monograph on the Orokolo), the population was 4,500. In the 1990s, it is in excess of 7,500. The term “Orokolo” generally refers to all Western Elema people living around Orokolo Bay, though it is also the name of one of the five Eleman languages, the major dialect of that language, and one of the five principal Orokolo villages—Arihava, Yogu, Orokolo, Auma, and Vailala. In both language and culture, the Orokolo are closely related to the Eastern Elema (or Toaripi). According to the Joshua Project the Toaripi, or East Elema, population in the 2020s was 88,000. [Source: Joshua Project]

Language: Orokolo belongs to the Eleman Language Family, a set of roughly five closely related, mutually intelligible non-Austronesian languages usually grouped within the Purari-Eleman stock. The family includes about eight dialects. As with cultural divisions, the main linguistic divide is between the Eastern and Western Eleman groups, which are separated by Raepa Tati—a more distantly related language spoken near the provincial capital at Kerema. Toaripi, or East Elema, is a Trans–New Guinea language.

History: European contact along the Gulf of Papua began well before 1900 and soon became widespread. Missionaries and labor recruiters were active early on, and by 1912 the region was considered fully “controlled.” By 1919, reports emerged of the “Vailala Madness,” one of the earliest recorded Melanesian cargo cults, occurring among the Orokolo. These movements are generally interpreted as responses to the rapid sociocultural upheavals brought by European presence and the accompanying erosion of traditional practices. “Vailala Madness” involved episodes of mass hysteria in which many people became dizzy, lost control of their limbs, and staggered about. The condition, locally called haro heraipe (“one’s head is turning around”), was linked to teachings that the spirits of the dead would return and that old ceremonies and traditions should be abandoned. In Eastern Orokolo villages, bullroarers and masks associated with sacred rites were removed from men’s houses and publicly burned before women and uninitiated boys. Although the movement persisted for several years, traditional practices eventually resumed, though in a more limited form.

Orokolo Religion and Culture

According to the Christian organization Joshua Project, about 98 percent of Orokolo people identify as Christian, with an estimated 10 to 50 percent considered Evangelical. Traditionally, however, the Orokolo did not believe in a supreme god or gods, and their religious concepts were somewhat diffuse. Their worldview included an animistic sense of mana—an impersonal force believed to reside in certain objects—but the core of their religion centered on two types of spirits: the spirits of the dead and the spirits of the natural world. Both were considered capable of influencing human life, but the latter—beings who once lived, whose deeds are told in myth, and who now inhabit particular features of the landscape—were the primary focus of ritual magic. Individuals sought to influence events by partially reenacting episodes from myth. [Source: Richard Scaglion, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Death and Afterlife: A death in the village suspends all but the most essential activities. Bodies are buried in shallow graves—traditionally within the village compound, though now outside it—with the feet pointed toward the sea. Mourning is intense and accompanied by a sequence of mortuary feasts. Spirits of the dead are believed to linger near their homes for a time, affecting the living, before eventually departing for a vague “land of the dead.”

Ceremonies and Religious Practitioners: Traditional Orokolo ceremonial life is exceptionally rich. Like other Elema groups, they maintain a bullroarer cult and perform a range of elaborate masked rituals. Their most important masked ceremonies are the kovave and the hevehe, the latter comprising a long, multi-stage ritual cycle that can take up to twenty years to complete. Although everyone practices some form of magic, certain part-time specialists are recognized for their skill in garden magic, diagnosing illness, healing, and sorcery. Traditional medical beliefs are closely connected to ideas about sorcery. Healers fall into two main categories: diagnosticians—“men who see sickness with their eyes”—and practitioners—“men who treat sickness.” Treatments often involve “blood sucking” to remove excess blood believed to cause pain, “phlegm sucking” in which healers spit out phlegm supposedly drawn from the patient, and the extraction of objects such as crocodile teeth or glass fragments thought to have been magically inserted by a sorcerer.

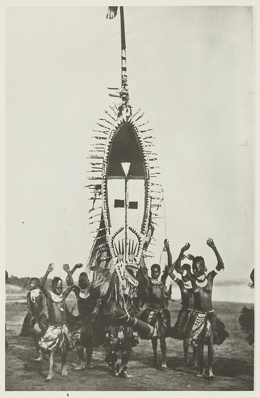

Art: Everyday and ceremonial objects among the Orokolo are elaborately decorated. Wooden items, including musical instruments such as bullroarers and drums, are carved with distinctive designs. The most striking examples of Orokolo art are the towering hevehe masks—intricately constructed and decorated structures reaching 9 to 10 feet in height. Elema people used to wear masks with a four-foot-long shark effigy on the top made from bark cloth and cane that was part of the hevehe ritual in which villagers invoked spirits of totem animals during the building of a new meeting house.

Orokolo Family, Marriage and Sex

The basic domestic unit of the Orokolo is the household, typically made up of a married couple and their children. In polygynous marriages, co-wives live together in the same household. Households may also include related individuals—such as widowed parents, unmarried or newly married siblings, or orphaned children—either temporarily or permanently. [Source: Richard Scaglion, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Marriage is guided by somewhat flexible social rules. Although most marriages are monogamous, polygyny is permitted. Traditionally, young men married soon after emerging from the age-grade seclusion that marked male initiation, creating a kind of marriage “season.” Young women generally married age mates at the same time. Ideally, women marry outside their own lineage but within their home village. Bride-price, consisting of shell ornaments and a live pig, is paid by the husband’s family to the wife’s family, and both sides exchange shell valuables. After marriage, the bride usually resides with her husband’s family, although matrilocal residence—living with the wife’s relatives—is also common. Marriages are generally enduring but can be dissolved through the return of shell ornaments.

Socialization: Among the Orokolo, direct coercion—especially physical coercion—is considered inappropriate. Children are no exception; by Western standards they are treated indulgently. Parents play frequently with their children and avoid giving direct orders, and even very young children enjoy considerable freedom of action. Children learn primarily by observing and imitating adults and are assigned few formal responsibilities. Boys pass through several age grades, which traditionally included a period of seclusion lasting six to twelve months around age 14 or 15, with each age grade marked by a distinctive costume. Women do not undergo formal age grades but do belong to age groups corresponding to those of men.

Kinship: The Orokolo recognize about ten named, totemic, exogamous patrilineal clans, each divided into patrilineal lineages. Every clan maintains a rich mythology—often expressed through distinctive art forms—relating to its ancestors and totems. Kinship terminology follows the Iroquois (bifurcate merging) system, which distinguishes parental siblings by both sex and relation. A father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters are addressed by the same terms used for Father and Mother. A father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers, however, are referred to by separate terms, typically translated as “Aunt” and “Uncle.” Parallel cousins—the children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister—are classified as siblings, while cross cousins—the children of opposite-sex siblings—are not considered siblings and are referred to by terms equivalent to “cousin.”

Sex: According to “Growing Up Sexually”: “Both male and female children were initiated at puberty although the females were not required to participate in all three stages of initiation. Females entered a period of seclusion at the time of their first menstruation and were required to perform a purification ritual before being released from seclusion. There were three stages of initiation as outlined by F.E, Williams (1930). They were: the 'terror', the 'seclusion', and the 'investiture' (Reay 1953). J. Newton wrote in 1985: “While secluded in the house it appears that there is some opportunity for socialization of the girl towards womanhood. Such norms of behaviour were verbalized in the old ceremonies described by Williams. On receipt of valuable ornaments 'a woman is told to lend an ear to what her husband says, and never to give him 'strong talk' in return; to accompany him wherever he goes; to be faithful to him; and to keep her hands off other women's property'. While there is no formal statement of such values in Koropata, the sedentary, passive existence of the girls does seem to make them amenable to advice. Older female relatives impress the importance of diligence in garden work and cooking. Girls are advised to marry a man who works well in the garden or an urban worker who provides food money and does not drink too much. Husbands should allow visits to natal families and should not lose their tempers. Sexual knowledge has already been imparted over a long period by older sisters and cousins. When she leaves the house, the pubescent girl does become more of an adult person in both productive and sexual matters. She is expected to have her own garden and be a responsible childminder, and she may begin to court young men, writing notes and whispering through floorboards at night. Actual sexual relationships do not generally occur until the girl is 16 or 17”. [Source:“Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin, Last revised: May 2005; Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

Orokolo Society, Life and Economic Activity

Orokolo social organization is highly complex, made up of multiple overlapping groups based on residence, descent, and age. In residential terms, the Elema are divided into tribes—of which the Orokolo are one—then into village groups, villages, and village segments called karigara. Each segment is tied to a men’s house (eravo). These eravo communities are further divided into bira'ipi, units that combine both descent and residence. Descent is organized through patrilineal clans and lineages, and social life is further shaped by fictive friendship ties and a system of named age groups that move through eight successive age grades. [Source: Richard Scaglion, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Orokolo are fundamentally egalitarian. Influence is earned through ability, personality, age, and experience. Each eravo community is divided into two halves, each headed by a nominal “chief,” and the village as a whole has a “village chief,” traditionally a descendant of early landholding settlers—often the same person as an eravo chief. In practice, these leaders have little coercive authority; decisions are made by group consensus. Without formal mechanisms of enforcement, social control relies heavily on public opinion, obligations of reciprocity, and fear of supernatural sanctions. Conflicts often arise over sexual infidelity or unequal exchanges, and disputes are resolved in group meetings mediated by influential men. Traditionally, each clan also had a bukari or clan “chief,” whose authority to settle disputes derived from his control of the clan’s bullroarer.

Orokolo adults are generalists, producing most of their own art, tools, clothing, and everyday items. Although some individuals are known for their skill in crafting canoes, drums, ceremonial masks, or carvings, such work is not commercialized. As in many small-scale societies, labor is divided largely by age and sex. Orokolo people often say that women’s work is in the village and men’s work is outside it, though this is only partly accurate. Women care for children, cook, clean, maintain the household area, feed pigs, collect water and firewood, and produce skilled craftwork such as nets. They also play a major role in making sago. Men fell sago palms, split the trunks, and scrape out the pith, while women wash, beat, and carry the processed sago home. Men are responsible for nearly all gardening, hunting, fishing, and construction.

Villages, often around 800 meters long but only about 54 meters wide, stretch in narrow bands along the beach. Large fenced areas separate sections of the village and control the movement of pigs. Open spaces between these fenced zones give the settlement the appearance of a series of elongated rectangles. Within each enclosure stand the houses—built in several styles but generally raised on piles, with veranda platforms and small entrances. Towering over the ordinary dwellings are the men’s houses (eravo), impressive structures about 30 meters long and 15 meters high, accompanied by one or two smaller versions used by boys. These rectangular compounds are kept remarkably clean and free of weeds.

Agriculture, Hunting and Fishing: The Orokolo depend heavily on the sago palm, which grows so abundantly that it requires no cultivation. Gardens—commonly fenced and divided into individually tended strips—provide other staples, including yams, taro, and bananas. Coconuts and domestic pigs are also important foods. Hunting, done with bows and arrows or spears and often assisted by dogs, targets wild pigs and cassowaries as well as smaller marsupials and birds. Fishing is practiced using nets, bows and arrows, or spears from elevated platforms in the water. Despite their coastal location, marine foods form only a minor part of the Orokolo diet.

Trade: Local trade consists mainly of practical barter and small exchanges of ornamental shells with groups to the east. Historically, their most significant intertribal exchange was the famous hiri trade with the Motu of Central Province. During seasonal droughts, the Motu sailed annually to the eastern Gulf of Papua to trade clay pots, shell ornaments, and stone blades for sago; this is how the Orokolo acquired their cooking pots. A pidginized form of Motu evolved as the trade language, blending Motu vocabulary with Toaripi–Orokolo grammar. Known as “Police Motu” or “Hiri Motu,” it later became the lingua franca of Papua and is now one of Papua New Guinea’s official languages.

Land is abundant, and ownership is flexible. In principle, land belongs to the bira'ipi—fluid groups defined by both residence and descent—but is effectively divided among larava, or patrilineal lineages. The senior male of each lineage formally “controls” the land, but in practice permission to use land is freely granted, and entire village segments may garden on land belonging to a single lineage. Inheritance follows the male line.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025