LARGE FERAL ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA

Feral animals are animals have been domesticated by himans and escaped human confinement or are descendants of such animals. Australia has problems with large feral animals such as water buffalo, camels, horses, donkeys and pigs — as well as small ones likes cats, foxes and rabbits — that were introduced from outside Australia and multiplied to out-of-control numbers. Herds and groups of large feral animals — descendants of stock that strayed from herds imported by pioneers — roam the sparsely settled areas.

Donkeys were introduced around 1870 as beasts of burden. Some 100,000 feral donkeys range across the outback gobbling up scarce vegetation. Goats were introduced before 1800. Two million goats turns pastures in desert eating plants up from the roots. Sambar deer were introduced around 1905. The heavier ferals, such as buffalo, which love to wallow in muddy ground, and wild ponies, do immense damage to natural bush vegetation and soils, particularly in the case of hoofed animals.

Large feral animals are particularly a problem in the Northern Territory, where there were 80,000 feral camels, a million feral pigs, 250,000 horses, and thousands of feral donkeys and goats in the early 2000s. Feral water buffalo have killed people there.

RELATED ARTICLES:

INVASIVE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: RABBITS, FOXES AND MOUSE PLAGUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

CATS (AUSTRALIA’S MOST DESTRUCTIVE INVASIVE SPECIES), ENDANGERED ANIMALS, CONTROL AND ERADICATION: ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, UNIQUENESS, HABITATS, CLIMATE ioa.factsanddetails.com

DANGEROUS ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: SPECIES, THREATS, TRENDS, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Feral Pigs in Australia

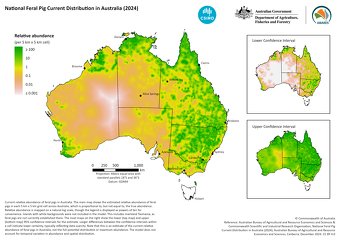

Feral pigs are a serious environmental and agricultural pest across Australia. They are found in all states and territories, particularly around wetlands and river systems. Pigs were introduced before 1800. Today, up to 23.5 million feral pigs are spread across about half of the continent, from western Victoria, through New South Wales into Queensland, and across northern Australia.. They are found in concentrations of 200 per square mile in some wetlands. Isolated populations can also be found on a few offshore islands.[National Geographic Earth Almanac, February 1992; [Source: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Australia government, 2011]

Feral pigs arrived in Australia with the First Fleet and first European settlers as a food source, and were transported around the country by 19th century settlers. Initially, the pigs that escaped or were allowed to wander were associated with human habitation, but truly feral colonies eventually became established. Their spread — mainly along watercourses and floodplains — is not well documented, but by the 1880s, feral pigs reached such numbers that they were considered a pest in parts of New South Wales.

Because they need to drink daily in hot weather, feral pigs are not found in the dry inland. In hot weather, they are usually found within two kilometers of water. Densities vary depending on conditions, with about one feral pig per kilometer square in eucalypt woodland, forest and grazing land, and as many as 10 to 20 per kilometer square in wetlands and seasonally inundated floodplains.

Feral pigs are active from late afternoon to early morning. They eat a wide range of foods — including plants and small animals, and they will scavenge on dead animals. Adult male feral pigs (boars) generally roam alone over an area of up to 43 kilometer square, while females (sows) range over areas smaller than 20 kilometer square. During dry conditions, groups of up to 100 pigs may gather around waterholes.

To breed, a male joins a group of 12 to 15 females. Feral pigs can breed from the age of seven to 12 months, and usually produce one or two litters of about six piglets each year. Many piglets are lost to dingoes and wild dogs, starvation and loss of contact with their mother. This rapid reproductive rate, similar to rabbits, can increase a population by up to 86 per cent each year in ideal conditions.

Damage Caused by Feral Pigs in Australia

Feral pigs are environmental and agricultural pests. They cause damage to the environment through wallowing, rooting for food and selective feeding. They destroy crops and pasture, as well as habitat for native plants and animals. They spread environmental weeds and could spread exotic diseases should there be an outbreak. [Source: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Australia government, 2011]

Feral pigs prey on native animals and plants, dig up large expanses of soil and vegetation in search of food and foul fresh water. Feral pigs will eat many things including small mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs, crayfish, eggs, earthworms and other invertebrates, and all parts of plants including the fruit, seeds, roots, tubers, bulbs and foliage. [Source: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Australia government]

Environmental damage caused by feral pigs can be hard to measure. By wallowing and rooting around the edges of watercourses and swamps, they destroy the vegetation that prevents erosion and provides food and nesting sites for native wildlife. They compete with native animals for food, pose a threat to ground-nesting birds, and can spread Distribution of feral pigs in Australia environment.gov.au environmental weeds. Feral pigs have destroyed breeding sites and degraded key habitats of the endangered white-bellied frog, orange-bellied frog and corroboree frog.

Feral pigs can cause serious agricultural damage. They produce losses of an estimated 20 000 tonnes of sugarcane each year. In some areas, they kill and eat up to 40 per cent of newborn lambs. Feral pigs are hosts for pathogens such as brucellosis and leptospirosis, and could also carry diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease, African swine fever and rabies, should those diseases be accidentally introduced into Australia. In dirt on their feet and fur, they can also spread plant pathogens such as Phytophthora cinnamomi, which causes plant dieback.

Feral pigs damage fences and water sources, and competing with stock for feed by consuming or damaging pasture. Feral pigs move around to new sites with food and water, and can breed rapidly to recover from control programs or droughts, and the impacts of feral pigs are intensified when their populations are large.

Control of Feral Pigs in Australia

Most states and territories have clear legislative requirements to ensure that feral pigs are controlled appropriately. The responsibility to reduce feral pig densities on their property rests with the land owner/manager, whether it be park ranger, private landholder or indigenous community. A National Feral Pig Management Coordinator was announced in late 2019, with a National Feral Pig Action Plan published in 2021.[Source: pestsmart]

A number of techniques are available to control feral pigs. In open country, mustering and shooting from helicopters can be effective in the short term, and pigs shot in the wild may be used for their meat. Shooting from the ground is considered to only be effective in small accessible populations. The market for wild pig meat is worth approximately $20 million annually. [Source: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Australia government, 2011]

Feral pigs can be controlled using poison grain or meat baits, usually with compound 1080 (sodium monofluoroacetate). Poisoning requires freefeeding of non-toxic bait prior to the toxic bait to attract the pigs. Free-feeding also reduces the risk of poisoning to non-target animals. Traps baited with grain can be used to control feral pigs. Traps are built near areas where pigs are active, such as watering holes. Land-holders often leave traps erected permanently, but only activating the gate when pig activity is evident. Electric fences are also used to protect small areas of high conservation priority from feral pigs.

Which ever method of control is used, the feral pig’s rapid breeding cycle has to be taken into consideration. Because feral pig populations have the reproductive ability to double in size annually, control campaigns need to be highly effective to have an impact Research suggests that rapid knockdown of a feral pig population by 70 percent or more can suppress its growth potential.

Dangerous Feral Water Buffalo in the Northern Territory

Water buffalo were introduced to Australia around 1820 from Indonesia for meat. Their introduction has been a major environmental disaster in the tropical wetlands of northern Australia, where its wallowing devastates native flora. Around 140,000 water buffalo, create wallows in the freshwater marshes of northern Australia. Major culling operations have reduced their numbers, but they are still common in the region. Occasionally they hurt somebody.

In 2001, a newspaper reported: A man's crawled almost a mile for help after being gored by a water buffalo in the remote Australian wilderness of Arnhem Land, according to police. The 40-year-old man was riding a bicycle home from a yacht club when he struck the beast, police senior Sgt Steve Bradley added. The man was taken to a nearby hospital before being airlifted to the Royal Darwin Hospital for surgery on a broken leg. The incident happened in the bauxite mining town of Nhulunbuy. "It proceeded to gore him in the legs, chest and arms," Sgt Bradley said. "He crawled about one kilometer to the mine site conveyor belt where he was picked up by one of the mine workers.""It's nothing life threatening. He was sitting up laughing and talking before he left," Sgt Bradley said. The cyclist apparently had not seen the water buffalo on the road in the dark and hit the animal, he added. [Source: December 4, 2001]

Nhulunbuy pest controller David Suitor said the animal probably gored the cyclist because it had been startled. He added the accident happened near where a jogger was chased by a water buffalo in 2000. Two cars were also wrecked after hitting a water buffalo on the same road, and a man was gored to death in 1997 in Nhulunbuy when he walked into one on his way home from a party.

In May 2005, a man was gored to death by a feral buffalo near Nhulunbuy. The Age reported: The body of the 46-year-old man was found in scrubland on the outskirts of Nhulunbuy in north-east Arnhem Land less than one kilometre from his home at an outstation. But a police investigation into his death has been compromised by his body being burnt in a bushfire. A group of about 25 buffalo has been running wild in Nhulunbuy, charging at locals and causing several traffic accidents in recent weeks. Police have shot two in the past couple of months, including one which wandered into the local fire station. "This is a tragic incident for the family," Nhulunbuy officer in charge Tony Fuller said. "Unfortunately occasionally incidents like these are bound to happen when we have a high concentration of people living in a remote area that is surrounded by natural dangers such as buffaloes, crocodiles and the like. "It is a risk that people acknowledge and one we try to limit and cannot necessarily control as we enjoy our outdoor lifestyle."

The dead man's family reported him missing on Sunday afternoon, after he left his house at the tiny East Woody outstation — about two kilometres from Nhulunbuy — to check the water supply line. His family became concerned after his two dogs returned later without him, prompting a police search which was hampered by a bushfire and thick scrub. His body was found the following day but it had been burnt in the fire, hindering NT major crime detectives and forensic officers flown in. [Source: The Age, May 27, 2005]

Local Parks and Wildlife Officer Phil Wise said authorities would step up their efforts to round up the buffaloes. "We will be trying to step it up a bit," Mr Wise said. "They are a dangerous animal and they are very unpredictable in nature. Some can be aggressive and some can be passive - you never know what you could be dealing with."

The animals have long been a pest to residents but the recent spate of incidents has been blamed on an increase in their numbers. They are thought to be drawn to Nhulunbuy by its abundant grass and water supply in the town's lagoon. First introduced into the Northern Territory in the 1840s, buffalo numbers in Arnhem Land have grown to more than 40,000. The fatality — the first in more than 12 years in the town —

Brumbies — Wild Horses in Australia

There are around 400,000 wild horses, know as brumbies, in Australia. By some reckonings it is the largest herd of wild horses in the world. Brumbies are smaller and weedier than standard horses. They are sometimes caught and broken and sold as children's ponies or used as breeding stock to produce tough trail mounts. Mature male brumbies are dangerous. They sometimes charge trail riders and fight other horses to death. There is a lot of anger when plans are floated for wild horse culls and sanctuaries exist where brumbies can run free with no worries..

Horses were introduced to Australia around 1800. The first brumbie herds are said to have originated in the mid-19th century when the O'Rorukers, early settlers, pulled up stakes and abandoned their livestock. The name brumby may have come from Maj. James Brumby, a late 19th century soldier who left his cavalry mounts to fend for themselves.

Before the age of the automobile there was a great demand for horses and brumbie catching was a lucrative side operation of mountain cattlemen. The famous A.B. (Banjo) Patterson ballad, “Man from Snowy River”, is about brumby running — chasing and roping wild horses in the high country of southeastern Australia. In the old days traps disguised as corals were constructed. These days the brumbies are located with dogs and pursued, sometimes for several days, and caught with ropes and halters,

Culling Brumbies

Brumbies are numerous enough in the Northern Territory to be considered a pest and are hunted and shot from helicopters because they compete for water and pasture sources with sheep and cattle. In 2000, 620 brumbies were culled from the air over three days in Guy Fawkes River National Park, reducing the park’s population of wild horses to 80. As an alternative to shooting brumbies from helicopters, some have suggested fencing off water holes and pastures.

Ching-Ching Ni wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Public outcry forced the government to halt the helicopter shooting in this part of the country, but it could not stop aerial and ground assaults, often carried out in secret, in other parts of the vast Australian outback. More than 10,000 horses are expected to be shot in Queensland in the next three years, according to an investigation by a newspaper in the state.[Source: Ching-Ching Ni, Los Angeles Times, Feb. 14, 2008]

Animal rights activists are looking for a gentler solution to horse overpopulation, but that pits them against an unlikely foe — environmentalists who want to stop the Australian version of the mustang from trampling pristine land. "Horses are exotic animals that don't belong in Australia," says Keith Muir of Colong Foundation for Wilderness, a Sydney-based environmental group that supports the culling of wild horses. "If kangaroos got loose in America, they would be like the horses here. You'll be shooting them like mad to try and control them."

Horse advocates want a federal policy that bans shooting everywhere and manages overpopulation through infertility drugs and adoption programs. Some have proposed using the horses as tourist attractions, much like the Dartmoor ponies of southwest England. In the late 2000s "Save the Brumbies," a non-profit group staffed by four full-time volunteers took in more than 250 horses. But that's a tiny portion of the number of animals rounded up with nowhere to go but the abattoir.

In 2023, the Australian government announced plans to kill 3,000 wild horses over four years at Kosciuszko National Park in New South Wales by shooting them from the air. About 19,000 wild horses lived in the park at that time. "There are simply too many wild horses in Kosciuszko National Park," Penny Sharpe, environment minister for New South Wales, said. "Threatened native species are in danger of extinction, and the entire ecosystem is under threat. We must take action. This was not an easy decision.”

Feral Camels in Australia

Camels were introduced to Australia around 1850. They were brought to help transport stuff across the dry Outback. Australian feral camels are of dromedaries (one-humped camels) like you find in the Middle East, but some are Bactrian camels.. Imported from British India and Afghanistan, they were used during the colonisation of the central and western parts of Australia. In the 19th century, camels were once the only way to get around the outback. The town of Maree was a great camel station and stopover on the three month journey from Adelaide to Darwin. The men who drove the camels were often Afghani.

Many camels were released into the wild after motorized transport replaced the use of camels in the early 20th century. With no natural predators and vast sparsely-populated areas in which to expand, the camels flourished and feral population grew fast. They have sometimes been killed for their meat. [Source: Wikipedia]

Today there are around 750,000 wild camels in Australia but estimates vary. Camels roam freely across an area of 3.3 million square kilometers (1.3 million square miles) encompassing the states of Western Australia, South Australia and Queensland, as well as the Northern Territory.

Problems Created by Feral Camels in Australia

The camels in Australia have had a huge impact on the outback environment. They are known to cause serious degradation particularly during dry conditions mainly by eating up sparse outback vegetation. They can damage fences, farm equipment and settlements, and also drink water which is needed by people and domesticated animals. "One of the biggest problems is that they drink large amounts of water. They gulp down gallons at a time and cause millions of pounds worth of damage to farms and waterholes which are used to water stock. They also drink dry waterholes belonging to the Aborigines," says explorer and writer Simon Reeve. "Camels are almost uniquely brilliant at surviving the conditions in the outback. Introducing them was short-term genius and long-term disaster."[Source: Sarah Bell, BBC News, May 19, 2013]

Lyndee Severin runs a one-million-acre ranch west of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory that has been overrun by the camels. "They do a lot of damage to infrastructure for us, so there's a lot of damage to fences. They break tanks, they break pumps, they break pipes, they break fences — fences have been our biggest concern," she told the BBC.

But her concern is not confined to her own business — the camels put pressure on native Australian species by reducing food sources and destroying their habitats. "They will just take everything in the landscape and if they destroy the trees and eat the grasses there's no kangaroos, no emus, no small birds if there's no trees, no reptiles," she says. Severin and her team shoot the beasts, often from helicopters, and leave them to rot where they fall. "It's not something that we enjoy doing, but it's something that we have to do."

In 2020 Aboriginal communities in the area of Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) — a sparsely-populated part of South Australia reported large groups of camels damaging towns and buildings. "They are roaming the streets looking for water. We are worried about the safety of the young children", says Marita Baker, who lives in the community of Kanypi."We have been stuck in stinking hot and uncomfortable conditions, feeling unwell, because all the camels are coming in and knocking down fences, getting in around the houses and trying to get water through air-conditioners." [Source: BBC, January 8, 2020]

In 2009, there were reports of thirsty camels turning on water tapes in central Australia. According to ABC: Camels are coming into communities in central Australia and turning on the taps, the Macdonnell Shire Council says. The shire has applied to the Federal Government for a $4.5 million slice of infrastructure funding to build camel-proof boundaries around 14 communities. Wayne Wright from the shire says thirsty camels are causing significant damage. "In a number of our communities it's quite common for camels to enter the community and if there are any taps adjacent to houses they're quite capable of either turning the taps on or knocking the taps off so they get water.” The intention is to put cattle grids at the entrances of the communities and place fencing around them. The fencing would also protect the communities from other feral animals, such as donkeys and horses. Mr Wright says the animals rip up plants and thwart efforts to improve the aesthetics of the communities. [Source: ABC, March 30, 2009]

Camels can also be a road hazard. In June 2023, a school bus driver died after he crashed into a pair of escaped camels at 5:00am in on a rural road in Livingstone Shire, Queensland,. The Miami Herald reported: The driver was headed to pick up students when he hit the animals and skidded down an embankment, investigators told Sky News Australia. The animals are thought to have escaped through a fence at The Big Camel farm, which isn’t far from where the crash occurred, the outlet reported. The driver, a man in his 40s, died at the scene, police said. He was the only person on board. The two camels were also killed, police said. Camel racer and breeder John Richardson said he was “devastated” after learning his animals had been hit, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported. “I’ve never had a gate come off like that,” Richardson told the station after finding one off its hinges. “I couldn’t work (it) out … they don’t try to get out (normally).” Livingstone Shire is about 405 miles northwest of Brisbane. [Source: Tanasia Kenney, Miami Herald, June 6, 2023]

Camel Culls in Australia

By 2008, it was incorrectly feared that Central Australia's feral camel population had reached to about one million and was projected to double every eight to 10 years. Pastoralists, representatives from the Central Land Council, and Aboriginal land holders in affected areas were amongst the complainants. An AU$19 million culling program was funded in 2009, and by 2013 a total of 160,000 camels were slaughtered, estimating the feral population to have been reduced to around 300,000. A post-kill analysis projected the original count to be around 600,000, an estimating error from the original number greater than the totality of the cull. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sarah Bell of the BBC wrote: Helicopters and modified off-road vehicles are used to round up the camels. In 2010 the Australian government endorsed a control plan, the Australian Feral Camel Management Project, which aimed to reduce camel densities through culling and mustering the animals for sale.Between 2001 and 2008 it was estimated there were up to a million feral camels in the outback, but thousands were culled under the project. Animals Australia, a pressure group, described this as a "bloodbath". For its part, RSPCA Australia says it would support a national approach to feral camel management, only if "the programmes are clearly explained and justified... and use the most humane methods available". [Source: Sarah Bell, BBC News, May 19, 2013]

But many farmers feel that they do not have much choice — and must do what they can with or without a national programme. The economic cost of grazing land loss and damage by feral camels has been estimated at 10 meters Australian dollars (£6.6m). "Killing them seems a tragic waste to many of us but the sheer logistics involved mean there is little choice. It is an issue I find more and more as I travel around the world. Humans introduce animals into fragile ecosystems. What do we do about it?" says Reeve, who is presenting a new series on Australia for BBC television "It's not enough for us to stand back and say I can't bear to see animals being killed. If we are going to make ourselves gods by meddling with an ecosystem then we have to take the responsibility to sort it out."

In January 2020, thousands of camels in South Australia were shot dead from helicopters during a five-day cull connected with pressures from extreme heat and drought. Some feral horses were also killed. The BBC reported: The marksmen who shot the animals come from Australia's department for environment and water. The slaughter took place in Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) described above. "There is extreme pressure on remote Aboirignal communities in the APY lands and their pastoral [livestock] operations as the camels search for water," says APY's general manager Richard King in a statement. "Given ongoing dry conditions and the large camel congregations threatening all of the main APY communities and infrastructure, immediate camel control is needed," he adds.

Alternatives ot Camel Culls in Australia

Sarah Bell of the BBC wrote: Helicopters and modified off-road vehicles are used to round up the camels. In 2010 the Australian government endorsed a control plan, the Australian Feral Camel Management Project, which aimed to reduce camel densities through culling and mustering the animals for sale.Between 2001 and 2008 it was estimated there were up to a million feral camels in the outback, but thousands were culled under the project. Animals Australia, a pressure group, described this as a "bloodbath". For its part, RSPCA Australia says it would support a national approach to feral camel management, only if "the programmes are clearly explained and justified... and use the most humane methods available". [Source: Sarah Bell, BBC News, May 19, 2013]

Ian Conway, who runs the 1,800 square kilometers Kings Creek cattle ranch, also near Alice Springs, believes there is a better way of managing their numbers — rounding camels up and selling them for their meat. Camels range over a vast area and can travel more than 40 miles in a day, so his team uses a helicopter to spot "mobs" of camels. They are then rounded up using heavily-modified off-road vehicles and put into a holding pen, before being sold to the Middle East.

Conway, who has been mustering animals for more than 40 years, says: "There's no difference to camel and beef, in fact to a lot of people who live on camel like we do, prefer it to beef." Some are also sold as riding camels, he adds. "The Saudis are always interested in them but they are looking for a specific camel. I've got a bloke who wants beauty camels at the moment. The bulls are no good. They like the cows because of their thin heads, but the cows have got to have their lips hanging, for what reason I don't know," says Conway.

He thinks a round-up is more humane than the alternative. "They just shoot them and nothing is done with them. We don't know if they lay there for days. I'd like them to come into the yard like this and be sold as meat or riding camels," he says. In many outback areas it is not cost-effective to round up and sell the camels. But Conway is convinced that with the right investment this could become a profitable way of protecting ranches and the environment.

Feral Deer Set to Became Australia’s “Next Rabbit Plague”

Deer are not native to Australia. Populations of feral deer increased tenfold between the early 2000s and early 2020s, with numbers too high to be managed by recreational hunting or other control measures. Lisa Cox wrote in The Guardian: Numbers of the invasive species are now so large in some parts of the east coast that a new national strategy by federal and state governments proposes establishing a “containment zone” to stop the spread of the animals westward across the country. Environment groups and some land managers say the plan is necessary to suppress a species that is emerging as “the next rabbit plague” and to prevent “wall-to-wall deer across the continent”. ‘‘The deer plague has already taken over most natural areas on the east coast,” the chief executive of the Invasive Species Council, Andrew Cox, said. “Scientists now predict that without action feral deer will inhabit every habitat in every part of Australia.” [Source: Lisa Cox, The Guardian, December 15, 2022]

Feral deer were introduced to Australia for hunting and farming. Over time, particularly with the decline of the venison industry in the 1990s, deer escaped, were released or were relocated for hunting. Their numbers have exploded due to a failure by governments to control small populations. In 1980 there were an estimated 50,000 deer in Australia. In 2022, the number is estimated to be one to two million and the range inhabited by feral deer has almost doubled.

While they have not received the attention of other invasive species such as feral cats, their effect on vulnerable ecosystems is also destructive: they overgraze, trample vegetation, damage cultural sites, cause erosion and degrade water quality. They also pose a biosecurity threat as potential carriers of disease and with large deer weighing in at more than 200 kilograms, are a major road safety risk. “A few years ago when I talked to the panel beater in Jindabyne, he said he was now fixing more cars from running into deer than from kangaroos,” said Ted Rowley, a beef cattle farmer.

Rowley was the chair of national working group for feral deer. He said in southeastern New South Wales the deer problem reduced the stocking rate on farms, particularly in dry years. He said land managers were spending tens of thousands of dollars a year just managing deer populations. “Many of the farmers and other land managers I work with see them as the next rabbit plague,” he said.

Under the draft strategy, large populations of deer along the eastern seaboard that are already too large to be eradicated would be controlled through measures such as aerial culling to keep their numbers at manageable levels. A national “containment buffer zone” would be mapped to stop the establishment of new large populations in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria and to stop populations in South Australia and eastern Tasmania from spreading west. The goal is to eradicate deer that enter the buffer zone. Small feral deer populations beyond the containment zone would also be eradicated. As a third measure, governments would develop — or reassess — specific plans to reduce deer in important environmental and cultural sites, such as Ramsar wetlands and heritage sites.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025