CATS IN AUSTRALIA

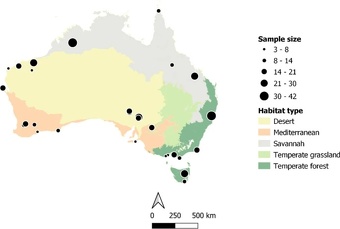

Data from telemetry studies on feral cats; Different colors represent the different habitat types; Black dots denote study locations, with dot size indicating the number of cats collared

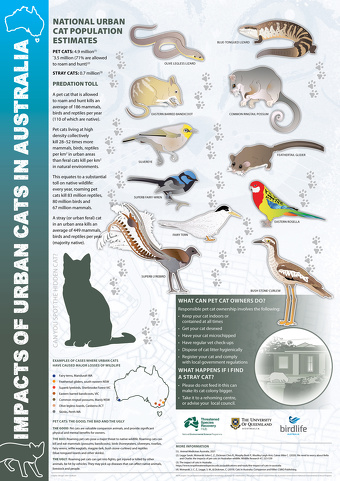

There are between 8 million and 11 million cats in Australia — about half of them pets and half wild feral cats (escaped pet cats or descendants of such cats). They are found throughout the mainland and on every major island of Australia. They are the second most popular pet by household (third most populous overall after dogs and fish). [Source: Wikipedia]

Cats (Felis catus) were initially introduced into Australia with the First Fleet of European in 1788. They were released throughout Australia in larger numbers around 1855 to control the population of another invasive species, European rabbits, as well as mice and rat populations. Domestic cats quickly expanded over the entire continent of Australia, killing many native species.

By the mid-1860s, cats were themselves at times considered a pest. At Barwon Park, Victoria in 1868, one of the first recorded cullings occurred, with over 100 feral cats found to be nesting in rabbit burrows. In the the 1880s, cats began to be promoted

under government policy for rabbit control and many were released in Victoria's Wimmera and the outback South Australia. By 1890 cats had spread to their approximate current mainland distribution. While the ability of cats to catch rabbits was often praised, rabbit trapping was considered a far more effective. Feral populations grew in remote Western Australia and Victoria at the same cats continued to be released throughout remote areas of Australia in an effort to control rabbits

Cats now inhabit 99.9 percent of Australia’s total land area. On a yearly average, an estimated 2.8 million feral cats roam the continent, but according to John Woinarski, a conservation biologist at Charles Darwin University and co-author of the book Cats in Australia: Companion & Killer, this number can balloon to 5.6 million in years of heavy rainfall. [Source: Anthony Ham, Smithsonian magazine, March 17, 2021]

RELATED ARTICLES:

INVASIVE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: RABBITS, FOXES AND MOUSE PLAGUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

LARGE FERAL ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA — CAMELS, PIGS, WATER BUFFALO, HORSES — DAMAGE, CONTROL AND CULLS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, UNIQUENESS, HABITATS, CLIMATE ioa.factsanddetails.com

DANGEROUS ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: SPECIES, THREATS, TRENDS, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Destruction Caused by Cats in Australia

Cats are the most destructive of the introduced, invasive and feral animals in Australia. They are the main drivers of extinctions in Australia, and have been the most economically costly species. Between 1960 and 2020, according to a 2021 study in PNAS by the experts sourced below, feral and unsuppervised domesticated cats cost Australians US$12.2 billion, mainly to control their numbers and limit their access through fencing, trapping, baiting and shooting. [Source: Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Flinders University; Andrew Hoskins, CSIRO, The Conversation July 29, 2021]

The Invasive Species Council has estimated that each year domestic and feral cats in Australia kill 1,067 million mammals, 399 million birds, 609 million reptiles, 93 million frogs, and 1.8 billion invertebrates.

An Australian government report released in February 2021 found that every year, each individual feral cat in Australia kills 390 mammals, 225 reptiles and 130 birds. That means that every year feral cats kill 1.4 billion native Australian animals — around the same number that died in the catastrophic 2019-20 bushfires when more than 73,000 square miles burned. Feral cats are not the only problem: The parliamentary report also found that Australia’s almost 3.8 million pet cats kill up to 390 million animals every year.[Source: Anthony Ham, Smithsonian magazine, March 17, 2021]

Cats and Endangered Animals in Australia

Cats have decimated wildlife in Australia, particularly West Australia, and significantly contributed to the extinction of at least 22 endemic Australian mammals since the arrival of Europeans. Feral cats are especially a threat to ground-dwelling birds and small marsupials such as bilbies, numbats, quokkas, quolls, bettongs, rock-wallabies like the black-footed rock-wallabies, and bandicoots like the western barred bandicoot, as well as numerous flying birds, reptiles, and frogs. Bilbies are marsupials with large, rabbit-like ears and pointed noses. Bettongs are small, hopping mouse-like marsupials. Feral cats are a major cause of decline for over 200 nationally threatened species, and they have already contributed to the extinction of more than 20 mammal species, such as the pig-footed bandicoot and the lesser bilby. [Source: Google AI, The Telegraph]

Cats kill two billion animals in Australia every year. There are 57 species in Australia labeled "highly susceptible" to cat predation, including 47 mammal species, according to a report from Australia's Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment, and Water.[Source: Katie Hawkinson, Business Insider, September 9, 2023]

Numbats have been driven to threshold of extinction by cats. According to Gizmodo: The numbat is the endearing marsupial anteater of Australia. Looking like a cross between a squirrel and a Tasmanian wolf, the numbat is endemic to Western Australia. Fewer than 1,000 individuals are thought to be alive today, and they are under threat from feral cats as well as foxes and habitat loss. [Source: Isaac Schultz, Gizmodo, November 25, 2021]

Orange-bellied parrots are a dazzling migratory parrot native to Australia. It’s been critically endangered since 2007, and a captive breeding program exists to help boost its numbers. But even in captivity, they aren’t safe from felines. In 2013, a cat snuck into an aviary holding the birds; according to Australia’s ABC News, a veterinarian said the birds died of head trauma, perhaps flying into walls in an attempt to get away.

Feral cats are highly efficient predators that hunt, kill, and eat a vast number of native animals every day, Particularly in the northern parts of Australia, they can have a devastating impact after fires, as they target areas where burnt vegetation makes it easier to hunt survivors of the fires. Anthony Ham wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Christine Ellis doesn’t like feral cats. As an Aboriginal Warlpiri ranger at Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary in central Australia’s Great Sandy Desert, she knows what they can do to Australia’s native animals: As she puts it, out there, “There are no stories without cats”. “Australia's biodiversity is special and distinctive, forged over millions of years of isolation,” says Woinarski. “Many mammal species that survived have been reduced to a minute fragment of their former range and population size, are now threatened and continue to decline. Left unmanaged, cats would continue to eat their way through much of the rest of the Australian fauna.” [Source: Anthony Ham, Smithsonian magazine, March 17, 2021]

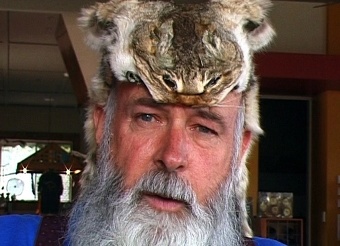

Dr John Wamsley — Australia’s No. 1 Cat Hater

Dr John Wamsley (born 1938), who runs Warrawong Wildlife Sanctuary in South Australia, is perhaps Australia’s best known cat hater, known for wearing a cat skin hat. He old ABC when he was child the Warrawong area “had potteroos and bandicoots and they were all there." By the time he was a teenager, many of his beloved animals were gone, he says, taken by cats and foxes. [Source: Prue Adams, ABC, March 27, 2005]

On the origin the cat hat Dr Wamsley said: "We were doing Yookamurra Sanctuary and eradicating cats, and a group of animal liberationists pointed out it was illegal to do anything about feral cats destroying my wildlife and they would take action against me if I did so I had to change the law. Proo was there and Adam O'Neill who had been shooting handed me this wonderful cat skin he'd shot at Arkaroola creek and Proo made it into a hat and put it on my head and we were going to a tourism awards night and I thought I'd wear it.

Dr Wamsley’s partner Proo Geddes said: "It was my idea for John to wear the cat hat, but he was the one that wore it and then wore all the flack that went with it and that was very much the relationship." "I knew exactly what newspapers had reported it, by where the death threats were coming from," Dr Wamsley said. "And it went on and on and on, it went several times around the world. People couldn't get enough. It changed the law; we can now shoot a cat on our sanctuaries even if it has a collar on and that's all we wanted to do.”

Difficulty of Cat Control in Australia

Conservation efforts to protect native wildlife from feral cats include: Fenced Exclosures, fenced reserves and islands where cats are fencing is erected to keep cats out of areas with vulnerable species insidel 2) Island Eradication: efforts to make islands, such as Kangaroo Island, free of cats to protect the unique wildlife that lives there. Exclosure fences capable of stopping cats requires complex construction and are extremely expensive. They are usually used to create a "safe haven" from cats. The best natural barrier against cats is water, which is why , makes control on islands less difficult.[Source: Wikipedia, Google AI]

Feral cats are very difficult to control as they are capable of bypassing control barriers and have adapted to harsh desert conditions by burrowing and obtaining water by preying on moisture-rich small desert marsupials. Cats are able to burrow under and climb over barriers and fences, breed prolifically and resist trapping and baiting. Shooting has its limitations and is viewed as ineffectual due to the high costs as cats are good at hiding if they detect a threat andbecause of their ability to climb, burrow and survive injury.

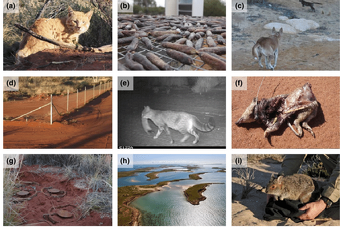

Some mammal species threatened by feral cats in Australia: a) greater bilby Macrotis lagotis; b) Tasmanian pademelon Thylogale billardierii; c) golden bandicoot Isoodon auratus; d) pale field rat Rattus tunneyi; e) juvenile woylie Bettongia penicillata; f) burrowing bettong Bettongia lesueur

Baiting is used as most native animals have a high tolerance to it, but its use with cats is seen to be generally not effective. Cats prefer live game and are tolerant to high doses, so specialised baits are required for cats. Baiting is expensive and its effectiveness as a means of control for cats is inconclusive. There are also issues with animal welfare groups in some areas that advocate for more humane alternatives. The idea of reintroducing Tasmanian devils has been proposed, due to their effectiveness in cat control in areas where they are present.

Eradicating feral cats from Australia remains a huge, if not impossible, challenge. Katherine Moseby, from the University of New South Wales, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “Control of feral cats is challenging as they are found in very low densities over large home ranges and are shy, making them difficult to locate. They are also extremely cautious in nature,” the Australian government said in a briefing paper on the problem. “Shooting cats is labour intensive and requires a lot of skill.” [Source: Nick Squires, The Telegraph, June 28, 2023]

Project Noah — Government Plan Control Cats in Australia

In February 2021, Australia’s federal parliament released a report that confirmed that cats were the primary drivers of mammal extinctions in Australia and recommended things like cat registration, nighttime curfews and spaying and neutering. Anthony Ham wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The report asserted that Australia leads the world with 34 species wiped out by cats and a further 74 land mammal species under threat. Faced with this crisis, the report launched “Project Noah,” a plan to increase the number of exclosures and recommended greater cooperation between all levels of government in dealing with Australia’s feral and pet cats. Some of the earlier critics are now behind this latest eradication effort to remove the island's last remaining invasive species. "Without this action, there will be serious long-term consequences for the majestic seabirds...and for the health of the island ecosystem as a whole," said Dean Ingwersen, Bird Australia's threatened bird network coordinator. [Source: Anthony Ham, Smithsonian magazine, March 17, 2021]

Set up in June 2020, the committee conducted hearings and received more than 200 submissions from scientists, conservation organizations and animal welfare groups throughout the second half of 2020. To reduce the impact pet cats have on native animals, the report recommended three major steps. 1) Pet owners should be required to register their cats, a measure designed to encourage responsible pet ownership and ensure revenue reaches local councils who enforce cat-control regulations. 2) Cat owners should be required to spay and neuter their cats to reduce the number of unwanted litters and the dumping of stray cats. And 3), Most controversially, the report also urged governments to mandate night-time curfews to prevent domestic cats leaving their homes after dark.

a) A feral cat Felis catus; b) Eradicat ® 1080 poison baits; c) dingo Canis dingo chasing a cat; d) cat exclusion fence at Matuwa; e) cat with a golden bandicoot Isoodon auratus in its mouth; f) radiocollared golden bandicoot preyed on by a cat outside the fence at Matuwa; g) padded foot-hold traps used to catch cats; h) Hermite Island, where feral cats and black rats Rattus rattus were eradicated and native mammals translocated to; i) spectacled hare-wallaby Lagorchestes conspicillatus being released on Hermite Island

Some conservationists hoped the report would go further. Night-time curfews “would benefit native nocturnal mammals, but won’t save birds and reptiles, which are primarily active during the day,” wrote Woinarski and others in response to the report. “Pet cats kill 83 million native reptiles and 80 million native birds in Australia each year. From a wildlife perspective, keeping pet cats contained 24/7 is the only responsible option.”

Cat containment measures even have the support of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), Australia’s peak animal welfare organization. RSPCA animal shelters take in 65,000 cats every year, and around 40 percent of these are euthanized. In a 2018 policy document that was cited favorably in the 2021 parliamentary report, the RSPCA agreed that “Cat containment regulations need to mandate 24-hour containment, rather than night-time curfews, if they are to significantly reduce wildlife predation, breeding of unwanted cats and cat nuisance.”

One area of commonality between animal welfare groups in the two nations is support for a program called Trap-Neuter-Release, also known as Trap-Neuter-Return, which involves trapping and spaying feral cats, then returning them to the wild. The report went on to consider further measures for controlling feral cats. One of these, gene-drive technology, would allow scientists to genetically engineer cats and make them, for example, less fertile or more susceptible to toxins. But the technology has only been tested successfully in yeast and other single-cell organisms. “It’s at least 20 years away,” says Woinarski, “and there’s no guarantee that it will work either.” “The ethics of it start to get tricky,” says Sarah Legge, a wildlife ecologist at Australian National University. “Think of the public’s reaction to genetically modified food. Then you’re talking about super-charging a cat. It just gets a lot harder.”

Australian officials want to curb the negative impact of pet cats with cat curfews, ownership limits, and indoor mandates in suburban areas. Several local governments in Australia already have such rules in place and the national government of Australia wants standardize the rules and give local governments more authority to expand them according to their needs. Despite a love for pet cats in Australia the Australian public appears largely supportive of the measures. "Maybe our job is easier in Australia, unfortunately, because we've lost so many species," Sarah Legge, professor at the Australian National University, told the New York Times. "The public is much more supportive of managing cats, including pet cat owners."[Source: Katie Hawkinson, Business Insider, September 9, 2023]

Aboriginal Cat Hunting

Anthony Ham wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Indigenous hunting of cats is a more immediate tool for reducing feral cat numbers. Aboriginal communities have hunted feral cats for food since at least the 1890s, and feral cats became an increasingly important part of the local diet throughout the 20th century as cats replaced native mammals in Australia’s Western Deserts. In the last two decades, cat hunting has also become a conservation tool. [Source: Anthony Ham, Smithsonian magazine, March 17, 2021]

As part of what was at the time the world’s largest feral cat eradication project, Ellis, the Newhaven ranger, would track cats on foot in the reserve as her ancestors once tracked kangaroos. She examined footprints in the sand to determine how recently the cats had passed, followed the tracks and then killed the cats with a single blow to the head, usually with a heavy iron bar. She still hunts feral cats in the unfenced areas of Newhaven, and from finding footprints to catching each cat rarely takes Ellis longer than an hour. The practice is, however, dying out as more Indigenous hunters abandon traditional hunting techniques in favor of vehicle-based hunting with guns, and younger generations of Indigenous populations move to the cities.

Traditional cat hunters operate only at Kiwirrkurra, an unfenced Indigenous community area covering 17,700 square miles in the Gibson Desert west of Newhaven. These hunts have helped to save local populations of two threatened species — the greater bilby, a small, large-eared native marsupial, and the great desert skink. But Indigenous hunting can’t operate on the scale required to counter the impact of feral cats.

Cat-Free Sanctuaries in Australia

Anthony Ham wrote in Smithsonia magazine: With its 23 ecosystems, Newhaven — an area in northwest Australia about one-third the size of the U.S.’ Yellowstone National Park — encompasses 1,023 square miles of sand dunes, salt lakes and red-rock escarpments. At the sanctuary’s heart is a fenced, 36-square-mile reserve from where Ellis and her colleagues from the Australian Wildlife Conservancy removed feral cats to create an area where native species could recover. [Source: Anthony Ham, Smithsonian magazine, March 17, 2021]

The fence at Newhaven was completed in March 2018 and the exclosure — an area built to keep unwanted animals out — was declared feral-predator-free the following year. Inside the fence, threatened and reintroduced native species such as the red-tailed phascogale and western quoll are making a comeback.

Newhaven is on the front line in Australia’s fight to protect its native animals from cats. The recently fenced area at Mallee Cliffs National Park in New South Wales is similar in size to Newhaven. Also in the state, Yathong Nature Reserve will soon enclose nearly 155 square miles of critical habitat. And the Australian Wildlife Conservancy plans to expand the Newhaven exclosure, one of eight such protected zones in its portfolio, to 386 square miles.

In 2019, the Australian Wildlife Conservancy notched a major conservation milestone at Newhaven when it reintroduced the mala, a miniature kangaroo-like marsupial that became extinct in the wild in the 1980s, to the exclosure.Free to roam without human interference and safe from feral cats, the mala and other reintroduced species are making a remarkable comeback, establishing territories and breeding successfully. Stepping inside the fenced area is like stepping back centuries. “You’ve got to watch where you step,” says John Kanowski, an ecologist and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s chief scientific officer. “A lot of these animals are burrowing or at least dig holes.”

Toxic-Goo Laser Used to Kills Feral Cats in West Australia

In 2023, Australian authorities introduced a new device to hunt and kill feral cats — lasers that squirt them with a deadly toxic goo. Nick Squires wrote in The Telegraph: The deadly new device uses lasers to identify the profile of a feral cat, so as not to accidentally target a native animal. The box-shaped machine, called a Felixer Grooming Trap, then squirts the cat with a toxic gel. The cat licks itself to try to get rid of the sticky substance, in the process ingesting the deadly gel. [Source: Nick Squires, The Telegraph, June 28, 2023]

Each time the device sprays a squirt of gel, it takes a photograph, so that conservationists can check whether it targeted the right creature. “In thousands and thousands of tests, it’s been able to correctly identify a feral cat as opposed to a native animal,” said Reece Whitby, Western Australia’s environment minister. “These feral cats are incredibly devastating on native animals. We need to do something — this is a major increase in our activity. We’re trying to give native species a fighting chance against this voracious predator.”

The solar-powered devices each contain 20 sealed cartridges of toxic gel and automatically reset after firing. The device can also identify and squirt foxes, which were introduced to Australia by European settlers and have a similarly devastating impact on native wildlife. They can even be programmed to play a range of sounds designed to attract feral cats and foxes. They are to be deployed at sites across Western Australia but may be extended to other states and territories, having been given approval by federal authorities.

The technology has been developed by a company called Thylation, which describes it as “a novel, humane and automated tool to help control feral cats and foxes”. Thylation has exploited that natural grooming behavior with the development of the Felixer. It says that feral cats are “notoriously difficult to control as they are reluctant to take baits or enter traps” but notes that “all cats are fastidious cleaners that groom regularly”.

The company has leased 16 of the devices to the government of Western Australia. Although the state spans a vast area, proponents of the technology say the devices can be very effective when strategically placed in spots with plenty of cat footfall — along fence lines, for instance, or in a narrow gully. They could also be used in relatively small, fenced areas where conservationists are trying to reintroduce threatened species. The devices are low maintenance and can be used where shooting cats might not be appropriate, according to experts from the Western Australian Feral Cat Working Group. They will be used in tandem with traditional strategies such as wide-scale baiting — Western Australia is to scatter up to 880,000 baits for feral cats each year. The units were successfully put to the test against cats and foxes in a conservation reserve called Arid Recovery in South Australia in 2020. “We put 20 Felixers out in an area where we had about 50 feral cats and we also had animals in there like bilbies and bettongs,”Katherine Moseby, from the University of New South Wales, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “We looked at how the cats declined over a six-week period and what we found was about two-thirds of the cats were killed by the Felixers,” Ms Moseby said. “We were able to show, quite convincingly, that the Felixers were successfully controlling cats in that area.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025