Home | Category: Jellyfish, Sponges, Sea Urchins and Anemones / Sea Life Around Australia

BOX JELLYFISH STINGS

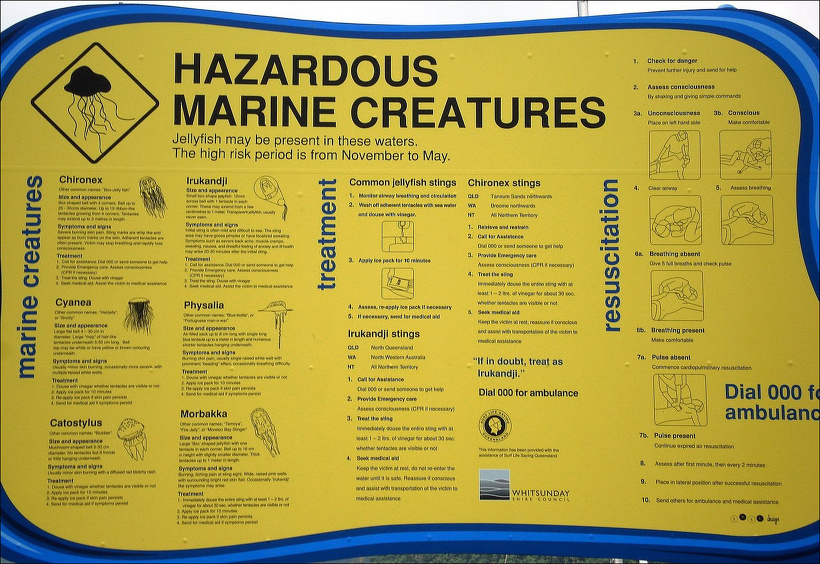

Box jellyfish warning sign in Australia Box jellyfish venom causes very rapid onset of circulatory problems. It has a high mortality rate because toxic reaction spreads very quickly throughout the body.The amount of venom injected into humans by box jellies has a big impact on whether a victim dies or lives. It is estimated that if six meters (20 feet) of tentacles comes into contact with human skin — and all nematocysts on those tentacles “fire” — the amount of venom injected is enough to cause death in just a few minutes. Humans that are stung typically have symptoms such as extreme pain, shortness of breath, and purple welts. Some victims have become irrational and suffered cardiac arrest. The symptoms usually begin within five minutes of being stung and can last up to two weeks before subsiding. [Source: Timothy Schmidt, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Box jellyfish don’t hunt humans but a random brush can lead to death within minutes. Survivors bear purple rope- like scars for life. Once while Hammer was carrying buckets with box jellyfish to his a truck, a breeze blew a single tentacle against some exposed skin on his arm. "I felt as if I had been branded by red-hot steel," he said. "My first instinct was to claw at my skin but I knew that dropping the bucket would be too dangerous. Wincing with pain, I managed to lift the bucket onto the truck. Then I examined the damage: a fiery welt, braided with characteristic bands of the box jelly's tentacle.”

"I was lucky," he continued. "Only about an inch of tentacle had stuck to my arm. It takes ten feet or more to deliver a fatal dose of box jelly venom. An inch was enough for me. A hundred that level of pain was unimaginable.” National Geographic showed some horrible photographs of sting victims from the Queensland Life Saving Manual. One was a little girl with nasty strings of welts on her torso and another was a child with scars that looked like thick concentration of varicose veins. Although both victims survived they were scared for life with macabre purple and scarlet tentacle marks. Survivors have described the pain as “like having a bucket of fire poured on me”.“Chironex is by far the world’s most venomous creature,” says Seymour. “It makes venomous snakes look like amateurs.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

BOX JELLYFISH: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

IRUKANDJI (EXTREMELY SMALL KILLER BOX JELLYFISH): CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

IRUKANDJI JELLYFISH: STINGS, VICTIMS AND DEATHS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR: CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION AND STINGS factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH-LIKE CREATURES: SIPHONOPHORES AND HYDROZOANS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH, SPONGES, SEA URCHINS AND ANEMONES ioa.factsanddetails.com;

JELLYFISH CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, BEHAVIOR AND DEVELOPMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH, PEOPLE, SWARMS, OTHER ANIMALS AND THE NOBEL PRIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH TYPES AND SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Box Jellyfish Victims

Box jellyfish stings can be fatal, with death occurring within minutes due to the highly potent venom which can cause rapid cardiac arrest. While official fatality records are scarce globally, estimates suggest dozens to over 100 deaths annually, with significant numbers reported in the Philippines and Australia. Most fatalities are documented in children and young adults in Australia. But not all of them are. in 1990 Chiropsalmus quadrumanus stung to death a 4-year-old boy in the shallows of a beach near Galveston, Texas. Chiropsalmus quadrumanus has also been reported in the waters off North Carolina, Brazil, Venezuela and French Guiana. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian magazine, June 2005]

An estimated 20 to 40 deaths occur each year in the Philippines, , though this is not officially recorded. At least 67 deaths have been associated with box jellyfish envenomation in Australia. Since 2008, there have been at least 15 recorded deaths from box jellyfish stings, including locals and tourists in Thailand.A Russian toddler died from a sting in Langkawi, Malaysia, in November 2025. A teenager died from a sting in Queensland, Australia, in February 2022, marking the second fatality in that region in 16 years. [Source: Google AI]

In 2008, 30,000 people were treated for jellyfish stings in Australia, double the number in 2005. Some of this was the result of box jellyfish expanding their range as waters off of Australia become warmer. In 2003, seven-year-old Jarred Crook was swimming at Mission Beach in Queensland, Australia. Suddenly he screamed. His grandfather pulled him from the water, but the writhing boy soon collapsed. With an hour he was dead of cardiac arrest — a victim of a box jellyfish. [Source: John Eliot, National Geographic, July 2005]

In January 1992 a Cairns man spent two nights in the hospital after being stung on the neck, chest and back. The man, a local newspaper reported, was swimming a 150 meters north of a stinger resistant enclosure and was pulled out of the water by friends. Lifeguards "dowsed" him with vinegar. "Ambulance officers treated the man with pressure bandages," the report said, "and although he was heavily sedated with painkillers...he was screaming and writhing in agony."

Box Jellyfish Fatalities in Thailand

In 2015, there a number of box jellyfish stings were reportedly around Koh Samui, Thailand, including the recent death of a 20-year old German woman. These stings occurred at Chaweng, Lamai, Mae Nam, Lipa Noi and on Ang Thong island. Nearby Koh Phangan also reports stings including two fatalities in the past 12 months. Other victims have been hospitalised.

In October 2015 the 20 year old woman from Germany decided to take a dip with a friend at night. Boxjellyfish.online and the Samui Times reported: It was a fatal mistake. Lamai Beach on Samui's east coast was rocked by agonising screams as the women ran out of the water and collapsed on the sand. Help arrived and the two women were splashed with vinegar. But tragically for one of the girls, she had received such severe box jellyfish stings that no amount of vinegar could save her. She died on the way to hospital. Her friend was kept in for observation and thankfully survived.

“A jet ski operation at Lamai spotted jellyfish in the region on the day. While some effort was made to spread the word, it wasn't enough. There are no physical warning signs at Lamai Beach. There is no system or network of communication to disseminate information and warnings. Phuket is also busy but it has a 'dangerous jellyfish' strategy. There are warning and information signs and vinegar poles at beaches around that island. This is also the case on Koh Chang, Koh Mak and others.

In July 2015, a 31 year-old woman from Bangkok died after being stung by a box jellyfish on the island of Koh Phangan. The incident coincided with the island's Full Moon Party and occurred at around 8:00pm. he woman, Chayanan Surinwent swimming at Haad Rin beach , along with 3 friends Ms Surin was severely stung on areas including torso, arms and legs and sadly died within minutes of being stung. In August 2014 a five-year-old French boy suffered the same tragic fate on the other side of the island. Thai authorities managing the box jellyfish situation in Thailand have urged Koh Phangan locals to act though they have continually resisted any prevention activities made available to them.

Protection From Box Jellyfish

From October to May box jellyfish can be found on the northern and northeast coast of Australia, as far east as Rockhampton behind the Great Barrier Reef, and as far west Broom. During the summer one doctor said: "it is quite unsafe to swim the ocean in tropical northern Australia." Fortunately for the Australian scuba diving industry, box jellyfish are not found very often around the Great Barrier Reef. They prefer the extremely warm and placid water found in northern Australia during the summer.

The box jellyfish season runs from about November to June in Queensland. They are more active during the day than at night. They rely on a visual system to hunt their prey and this of course is easier during daylight. Many attacks happen at night because can’t see the jellfish. Box jellyfish are more or less transparent and are almost as difficult to spot during the day than at night. The only way to swim (day or night) and be 100 percent protected is to wear a lycra suit. Such suits are produced in Australia by the Stinger Suit Company.

Precautions against box jellyfish include staying out of the water, swimming inside stinger nets in "swimmer resistant" areas , wearing protective clothing such as pantyhose and tight fitting shirts. Surfers wear pantyhose on both their legs and arms to protect themselves from box jellyfish stings. Scientist put on long pants, long-sleeve shirts and gloves taped to their wrists when handling buckets of jellyfish on land. Lifesaver warn swimmers to wear lycra, but neoprene scuba diving outfits are not necessary. The reason for this is that box jellyfish have short singer capsules are too short to puncture skin covered by a thin layer of clothing.

Treatment for Box Jellyfish Stings

In the case of a severe box jellyfish sting, signs in northern Australia advise: 1) flood the sting area with vinegar; 2) give artificial respiration if breathing stops; and 3) give closed chest massage if the heart stops. For minor stings one should flood the sting area with vinegar and then apply a soothing cream or lotion. Health advisories say: if stung immediately pour at least two liters if vinegar over the adhering tentacles to deactivate the stinging cells. This does not reduce the pain. Do not rub the victim's skin, keep them immobile and use artificial respiration until medical assistance can be obtained.

There is an antivenin for box jellyfish. It was developed in the 1970s by injecting a small amounts of venom into sheep who then in turn produced antibodies with anti-venom. "It can be very effective," says one doctor, "Normally breathing often begins almost immediately, and pain relief usually occurs within minutes. Later scarring is frequently reduced."

Fatalities are now in decline. Many beaches now use stinger nets to keep them away from swimmers. City councils refer to computer models that predict the end of the box jellyfish season Because vinegar stops Chironex from firing venom, Australian lifeguards keep it on hand. [Source: John Eliot, National Geographic, July 2005]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025