Home | Category: Birds, Crocodiles, Snakes and Reptiles

GOANNAS

Goannas are monitor lizards that live in Australia, New Guinea and some nearby island. Monitor lizards are lizards in the genus Varanus, the only extant genus in the family Varanidae. Known as varanids, they are native to Africa, Asia, and Oceania and have been introduced to some places in the Americas. About 80 species are recognized. They range in length and weight from tiny short-tailed monitors — which are 20 centimeters long and weigh 20 grams — to the Komodo dragons — which are up to three meters long and weigh up to 54 kilograms. [Source: Wikipedia +, Jennifer C. Ast, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The name goanna is derived from iguana — the name of a group of lizards that live in the Americas. Early European settlers in Australia likened goannas to iguanas. Over time, the initial vowel sound was dropped. The Australian term possum was derived from American opossums in a similar way. [Source: Wikipedia]

Goannas occupy a wide range of habitats, and different species can be primarily surface dwelling, burrowing, arboreal (live mainly in trees), or saxicolous ( living on or among rocks). Goannas have forked tongues. Their legs act as heat exchangers. They heat up and cool down faster than the rest of the body and the veins can be enlarged or constricted depending on how much hot or cold blood needs to circulated through the lizard's system. Most goannas either freeze (lying flat on the ground, and remaining very still until the danger has passed) or run if detected.

In late 2005, University of Melbourne researchers discovered that all monitors may be somewhat venomous. Previously, bites inflicted by monitors were thought to be prone to infection because of bacteria in their mouths, but the researchers showed that the immediate effects are caused by mild envenomation. Bites on the hand by Komodo dragons (V. komodensis), perenties (V. giganteus), lace monitors (V. varius), and spotted tree monitors (V. scalaris) have been observed to cause swelling within minutes, localised disruption of blood clotting, and shooting pain up to the elbow, which can often last for several hours. [Source: Wikipedia] See KOMODO DRAGON FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING BEHAVIOR AND VENOM factsanddetails.com

RELATED ARTICLES:

GOANNAS (MONITOR LIZARDS) factsanddetails.com

BIGGEST AND MOST COMMON MONITOR LIZARDS: ASIAN WATER AND BENGAL MONITORS factsanddetails.com

MONITOR LIZARDS OF NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LIZARDS IN AUSTRALIA: TYPES, SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

THORNY DEVILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

FRILLED LIZARDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SHINGLEBACK AND BLUE-TONGUED LIZARDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGONS: CHARACTERISTICS, HABITAT, SENSES, MOVEMENT factsanddetails.com

REPTILES: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, THREATENED STATUS factsanddetails.com

LIZARDS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES, ODDITIES factsanddetails.com

CROCODILES IN AUSTRALIA: HISTORY, SPECIES, BIG ONES, DWARVES, BATS, SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

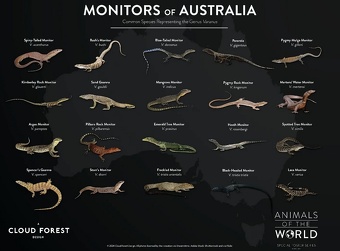

Goanna Species

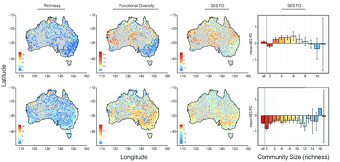

Maps of Australia showing patterns of richness (number of species) and functional diversity for monitor lizards (top row) and for monitor lizards and faunivorous marsupials together (bottom r row), with warmer colors indicating greater variety, from “Phylogenomics of monitor lizards and the role of competition in dictating body size disparity”, Researchgate

Australia is home to a diverse range of goanna species, belonging to the genus Varanus (comprised mostly of monitor lizards). There are at least 25 species found in Australia, accounting for roughly a third of all monitor lizard species. Goannas are carnivores known for their predatory nature. They have sharp claws, make a hissing noise and can be aggressive and dangerous. Large ones can take off a hand. Goannas are prominent in Aboriginal mythology and folklore. Aboriginals also like to eat them. Lace-backed goannas are considered a delicacy.

Perentie (Varanus giganteus) are the largest goannas. Found in arid and semi-arid regions in central Australia, they can reach lengths of two meters (six feet) long and are the size of adolescent children. Some pygmy goannas are quite small. Short-tailed monitor lizards (Varanus brevicauda) are one of the smallest goanna species, reaching only about 20 centimeters (8 inches) in length. Lace monitors (Varanus varius), also known as tree goannas, live in eastern Australia. Heath goannas (Varanus rosenbergi) are found in southern South Australia and considered vulnerable in some regions. [Source: Google AI]

Some goannas have incrediblly beautiful markings,. Spencer's goanna has a black tongue and a yellow stomach. Stripe-tailed goannas (Varanus caudolineatus) are a smaller goanna species with a distinctive stripe pattern. Spotted Tree Monitors (Varanus scalaris) are small, arboreal goannas found in northern Australia. Yellow-spotted monitors (Varanus panoptes): Another arboreal species found in northern Australia. Several goanna species spend a lot of time in the water. Merten's water monitors (Varanus mertensi) are highly aquatic and found in northern Australia. Like all, reptiles, they must lay their eggs on land.

Sand Goannas

Sand goannas (Varanus gouldii) are common, ground-dwelling monitor lizards, found throughout Australia. Also known as sand monitors and Gould's goannas, they are widely distributed in both arid and tropical areas in deserts, woodland, grasslands, chaparral forest, and rainforest. They are associated with sandy soils and more often observed in the wet season than in the dry season. [Source: Kirsten McDonnell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|; Wikipedia]

Sand goannas are fairly large monitor lizards, reaching lengths of 140 centimeters (4.6 feet) and weighing as much as six kilograms (13 pounds). They are greenish-gray with ringed small yellow spots all over their bodies. The spots are faint towards the neck but are more prominent on the tail and lower torso. These lizards’ snake-like head is flat with the yellow pattern on the sides. The bottom quarter of the tail is long and solid yellow. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Adult female are not as long as males and weigh one-third of what adult males weigh.

Sand goannas are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. They have traditionally been eaten by Aboriginals and important animals in many Aboriginal cultures. Varanids are protected by state and federal laws. The largest threats to these lizards are poachers, vehicle traffic, birds of prey and habitat loss and degradation.

Sand Goanna Behavior, Diet and Reproduction

Sand goannas are terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active during the daytime), sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary. To get warm sand goanna bask in the sun, and retreat to their burrows to cool down. Males have larger territories and are more active than females. The entrance of a goanna burrow is often beneath a flat rock, a small shrub, or a fallen log. Sand goanna often use the warrens of introduced rabbits for shelter instead of constructing their own burrows. The burrows are important for providing protection from predators and weather. [Source: Kirsten McDonnell, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

While foraging, goannas' often dig for prey. When they do this they are often so absorbed in the activity they expose themselves to predation. When walking, goannas carry their bodies high off the ground and only a small portion of the tail near the tip touches the ground. When running the tail is lifted completely off the ground. When approached sand goannas adopt a threatening posture: they arch their backs, inflate their neck, and hiss loudly. They can bite, scrape with their claws and make powerful side-swipes with their tail. Sand goannas also reportedly sometimes rear up on their hind legs in response to a threat. |=|

All goannas and monitor lizards are carnivorous and active predators. Sand goannas primarily feed on mammals and, reptiles, but also eat birds, amphibians, reptile eggs, insects, and crustaceans. Many of the animals they eat are scavenged road kills. Goanna can cover long distances in their search for food, digging up prey in loose soil and decaying vegetation. They obtain most of their water from their food. Goannas walk with their snout held close to the ground when foraging. Their long forked tongue flicks in and out transferring scents to the Jacobson’s organs. They can quickly locate hidden prey this way, even if it is some distance underground. They then use their sharp claws as well as their snout to dig out the prey. Cannibalism has been observed among sand goanna. It may be just them feeding on carrion. |=|

Sand goanna breeding occurs during the wet season. Male goannas seek out the burrow of a female and and when they find one build a burrow of their own a few meters away. Over several days the male and female spend an increasing amount of time together. According to Animal Diversity Web: Eventually, they begin to copulate. They continue to mate over and over again for several days. During this period of intense breeding activity, the pair may share the same burrow. After many days the intensity of copulation declines and the goannas separate and forage independently.

When it is time to lay the eggs, the female locates an active termite mound. She digs a tunnel towards the center of the mound 50 to 60 centimeters (1.6 to 2 feet) deep. At the end of the tunnel she digs a large cavity. The female then sits on the top of the mound and lays 10 to 17 eggs into the tunnel. Afterwards she refills the tunnel, and the termites reconstruct the mound around the goanna eggs. The termites regulate the temperature and humidity, so this is an excellent place for development of the eggs. Delayed fertilization has been recorded in this species.

Perentie

Perentie (Varanus giganteus) are monitor lizard and among the largest living lizards on earth, after Komodo dragons, Asian water monitors, and crocodile monitor. Found west of the Great Dividing Range in the arid areas of Australia, they are is rarely seen because of their shyness and the remoteness of the places they live. Perentie are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. [Source: Wikipedia]

Perentie are found in the arid desert areas of Western Australia, South Australia, the Northern Territory, and Queensland. Their habitats consist of rocky outcroppings and gorges, with hard-packed soil and loose stones. Among many Aboriginal cultures, these goannas have totemic significance and are dreaming, as well as being a favorite food for desert Aboriginal tribes and as bush tucker for Europeans. Perentie fat was used for medicinal and ceremonial purposes.

Perenties are the largest living species of lizard in Australia. They can grow to lengths of 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) in) and weigh up to 20 kilograms (44 pounds). There are unverified reports of one as large three meters (9.8 feet) and 40 kilograms (88 pounds). Perenties are very lean for a a large monitor lizard. Komodo dragons, Asian water monitors, crocodile monitors and rock monitors are much bulker.

Perentie Behavior and Diet

Perenties are good diggers. They can excavate a burrow for shelter in a matter of minutes. Their long claws enable them to climb trees easily. They often stand on their back legs and tails to gain a better view of the surrounding terrain. This behavior, known as "tripoding", is quite common in monitor species. Perenties are fast sprinters and can run using either all four legs or just their hind legs. The perentie can lay its eggs in termite mounds or the soil. [Source: Wikipedia]

If cornered, perenties stand their ground and rely their claws, teeth, and whip-like tail to defend themselves. They can inflate their throat and hiss as a defensive or aggressive display and can strike at opponents with its muscular tail. It may also lunge forward with an open mouth, either as a bluff or attack. The bite of a perentie can do much damage, not only from the teeth but also because of venom and oral secretions.

Perenties are apex predators. Adults have no natural predators. They are highly active carnivores that feed mostly on reptiles, small mammals, and less commonly birds such as diamond doves. They hunt live prey, but also scavenge carrion. Prey is typically swallowed whole, but if it is too large, chunks are ripped off with the claws and teeth. Reptiles that perenties they eat include lizards such as skinks, central bearded dragons, long-nosed water dragons and other agamids and less commonly snakes. Among their most common prey are other monitor lizard species such as ridge-tailed monitors, black-headed monitors, Gould's monitors, and even Argus monitors and even other perenties. There is one case of two-meter (6.6-foot) perentie killing and eating a 1.5 meter (5-foot) perentie.

Perenties that live in coastal and island areas eat large numbers of sea turtle eggs and hatchlings and hide under vehicles to ambush scavenging gulls. Mammalian prey includes bats, young kangaroos other small marsupials, and rodents. They have also been occasionally seen foraging for food in shallow water. They are able to kill kangaroos and dismember those too large to be swallowed whole using their powerful forelimbs and claws.Although adults feed predominantly on vertebrate prey, young perenties eat mostly arthropods, especially grasshoppers and centipedes.

Lace Monitors

Lace monitors (Varanus varius) are also known as tree goannas. They are large monitor lizard that can reach two meters (6.6 feet) in total length and 14 kilograms (31 pounds) in weight. Lace monitors occur on the ground and in trees open and closed forests in eastern Australia, ranging from Cape Bedford on Cape York Peninsula to southeastern South Australia. They forage over relatively long distances — up to 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) a day — and are mainly active from September to May. When they are inactive in cooler weather they shelter in tree hollows or under fallen trees or large rocks. Lace monitors not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. [Source: Wikipedia]

Goanna remains have been found in middens in what is now Sydney. The Tharawal ate lace monitors eggs after collecting them in sand on riverbanks in the Nattai and Wollondilly. The Wiradjuri people eat the lizards themselves, preferably, according to local wisdom, chossing ones that came down from trees as those that had eaten on the ground tasted of rotting meat. Lace monitors are bred in captivity for the pet trade.

Venom glands in lace monitors have been confirmed. The venom is similar to that produced by snakes but not enough to cause serious harm. Bites on the hand by lace monitors have been observed to cause swelling within minutes, localised disruption of blood clotting, and shooting pain up to the elbow, which can often last for several hours. In vitro testing has shown that lace monitor mouth secretion impacts platelet aggregation, drops blood pressure and relaxes smooth muscle (the same activity as brain natriuretic peptide). Washington State University biologist Kenneth V. Kardong and toxicologists Scott A. Weinstein and Tamara L. Smith, have cautioned that labelling these species as venomous oversimplifies the diversity of oral secretions in reptiles, and overestimates the medical risk of bite victims.

Lace monitors are close to the top of the food chain, though dingo packs, wedge-tailed eagles, and wild boars occasionally prey upon them. Monitors can potentially live to reach over 20 years of age.

Lace Monitor Characteristics and Patterning

Lace monitors are the second-largest monitors in Australia after perenties. Their snout–vent length (SVL), which doesn’t include the tail, is 76.5 centimeters (2.5 inches). The tail is long and slender and about 1.5 times the length of the head and body. The tail is cylindrical at its base, but becomes flatter towards the tip. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are generally larger than females.Males reach sexual maturity when they have a SVL of 41.5 centimeters (1.4 feet), with a maximum SVL of 57.5 centimeters (1.9 feet). Females reach sexual maturity when they have a SVL of 38.5 centimeters (1.3 feet). [Source: Wikipedia]

lace monitor range

Lace monitors are found in two forms: the normal phase and Bell's phase. The normal, main form is dark grey to dull bluish-black with numerous, scattered, cream-coloured spots. The head is black and the snout is marked with prominent black and yellow bands extending under the chin and neck. The tail has narrow black and cream bands, which are narrow and get wider towards the end of the tail. Juveniles have more defined and prominent banding, with five narrow black bands on the neck and eight bands on the body.

Bell's phase lace monitors have a base color of yellow-brown or yellow with fine black mottling and broad, black or dark brown bands from the shoulders to the tail. The top of the head is black. This form is typically found in mainly southeast Australia west of the Great Dividing Range from Woodgate, Eidsvold, and Mitchell in Queensland to Bourke, Macksville and Port Macquarie in New South Wales. It has also been reported from Healesville, Rushworth, and Murchison in Victoria and the Flinders Ranges in South Australia.

Lace Monitor Behavior. Diet and Reproduction

Despite its large size, lace monitors are agile climbers. One was observed climbing a brick wall to seek shelter in a thunderstorm. Young lace monitors are more arboreal than adults. They often spend most of their adult lives in the same area; one individual was recorded living in the same tree for years.A field study in Burragorang, New South Wales found that males over five kilograms ranged over home territories of 55 to 75 hectares (136 to 185 acres). They were much less active and moved around less in winter.

Lace monitors are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and feed primarily on carrion — already dead carcasses of other wildlife. Captured prey includes insects, reptiles and small mammals. Birds, eggs, young birds and mammals make up a larger portion of their diet in spring and early summer. They frequently attack the large composting nests of scrub turkeys to steal their eggs, and often show injuries on their tails inflicted by male scrub turkeys pecking at them to drive them away.

Lace monitors search for food on the ground, retreating to nearby trees if disturbed. They also forage in areas inhabited by people, occasionally raiding chicken coops for poultry and eggs, and rummage through garbage bags and rubbish bins in picnic and recreational areas. A 2012 study in Gippsland found that lace monitors near two rubbish areas were around twice as heavy and there were 35 time more lizards than populations in natural forests. Lace monitors, particularly larger ones, declined in numbers when cane toad entered their range. At the same time, lace monitors are abundant in some areas where cane toads had been established for many years. Fieldwork published in 2016 found that larger individuals were less cautious in what they ate, but all lace monitors quickly learned to avoid toads after they had been poisoned.

The breeding season of lace monitor lizards in temperate areas is in the summer. As many as six males may gather around a receptive female to try and court her. Males fight each other by grappling while standing on the hind legs. Mating occurs over several hours. Females lay an average of eight eggs in active termite nests either on the ground or in the trees, although they may lay as many as 12 eggs. When such nests are in short supply, females often fight over them or lay the eggs in burrows and perhaps hollow logs. The eggs overwinter to hatch six to seven months later. Hatchlings remain around the nest for about a week or more before leaving the area. Females may return to the same termite nest to lay their next clutch of eggs.

Mertens' Water Monitors

Mertens' water monitors (Varanus mertensi), often misspelled Mertin's water monitor, are a species of monitor lizard named after German herpetologist Robert Mertens. They are found in coastal areas and inland water bodies across much of northern Australia, from the Kimberley region of Western Australia, across the Top End of the Northern Territory and the Gulf Country, to the western side of the Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland. Among all monitor species, including even the water monitors of the Philippines and Southeast Asia, Mertens' water monitors are morphologically the most well adapted to an aquatic lifestyle. They are able to seal their upwards facing nostrils when underwater and are the only known monitor species capable of using their sense of smell to locate and capture prey underwater. They can also swallow prey underwater — a skill which has ability not been reported in any other monitor species other than Borneo earless monitors (Lanthanotus borneensis).

Mertens' water monitors reach lengths of about two meters (6.6 feet), including their tail. They are dark brown to black on their back and sides, with many cream to yellow spots. Their underparts are paler — white to yellowish — with grey mottling on the throat and blue-grey bars on the chest. Their tail — which is key to swimming — is vertically flattened with a high median dorsal keel, and is about 1.5 times the length of head and body. The nostrils of Merten's water monitor are situated near the top of the snout, and can seal shut when underwater.

Mertens' water monitors are wide-ranging, opportunistic predators. They are strong swimmers and seldom far from water. They are often seen basking on midstream rocks and logs, and on branches overhanging swamps, lagoons, and waterways. When disturbed, they enter the water and can stay submerged for long periods, even sleeping underwater. Mertens' water monitor spend a lot of time actively foraging and feed both on land and in the water, mainly on fish, frogs, crabs, crayfish, shrimps, amphipods, and carrion, also taking terrestrial vertebrates, insects, spiders, and human rubbish when available. One study found that freshwater Holthuisana crabs, make up 29 percent to 83.7 percent of the biomass found in gut and scat samples, followed by 11.5 percent for fish. They have a good sense of smell and may dig up prey when foraging, including the eggs of freshwater turtles. While eggs and frogs are infrequently eaten, large amounts of them are eaten when found. Arthropods including spiders, beetles and water bugs. While frequently eaten, they make up a small proportion of ingested prey biomass.

Mertens' water monitors are classified as endangered in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. They are threatened by the spread of cane toads through their range, by being poisoning from eating them and habitat loss and degradation. Females lays eggs in a burrow. Egggs are generally laid early in the dry season and hatch in the following wet season, within 200–300 days after laying, depending on temperature. Hatchlings able to enter the water and swim immediately after hatching.

Spiny-Tailed Monitors

Spiny-tailed monitors (Varanus acanthurus) are also known as Australian spiny-tailed monitors, ridge-tailed monitor, Ackie dwarf monitors, and ackie monitor. They are adapted for life in the desert and arid environments and occur in northern Western Australia, in the Northern Territory and in the western and north-western parts of Queensland. They like arid rocky ranges and outcrops. There are three subspecies: 1) V. a. acanthurus of northwestern and northern Australia from Broome on the west coast, through the Kimberley and the Top End, to the Gulf of Carpentaria; 2) V. a. brachyurus of western and central Australia, Queensland, found in the center, western, and eastern parts of the ackie's total range, as far west as Carnarvon and as far east as Mt. Isa.; and 3) V. a. insulanicus of Groote Eylandt and the islands of the Wessel group.

Spiny-tailed monitors are smallish monitor lizard, reaching lengths of 70 centimeters (2.3 feet), including the tail. The tail is about 1.3 to 2.3 times as long as the head and body combined. The lizard’s back dark brown with bright-yellowish to cream spots, which often enclose a few dark scales. Spiny-tailed monitors look a lot like black-spotted ridge-tailed monitors and northern blunt-spined monitors and can be distinguished from them by the presence of pale longitudinal stripes on the Spiny-tailed monitor’s neck

Spiny-tailed monitors are diurnal, solitary ground-dwellers who spend a lot of time foraging. They tend to shelter under rock slabs, wedged among boulders or in rock crevices, and in burrows. Only rarely do they hide in spinifex bushes. Sheltering underground helps they keep cool and conserve water on their hot habitat. They prey mainly on arthropods, such as grasshoppers, beetles, cockroaches, spiders, isopods, caterpillars, cicadas, snails, stick insects, centipedes, crickets, ticks, small lizards such as skinks, geckos, dragon lizards, and possibly smaller monitor lizards About 70 percent of their water intake comes from food.

In captivity, female spiny-tailed monitors lay up to 18 eggs. The young hatch after three to five months of incubation, and measure 15 centimeters (6 inches) when they hatch. Males most likely mature at 30 centimeters (12 inches) snout-vent length, while females mature at 25–36 centimeters (10–14 inches) snout-vent length. Ovulation occurs in August and November. The eggs are deposited in self-dug tunnels. In the wild, females sometimes share massive burrows and nesting communally.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025