Home | Category: Birds, Crocodiles, Snakes and Reptiles

CROCODILES IN AUSTRALIA

Large saltwater crocodile caught in the Johnstone River, Innisfail, in 1903; the dead crocodile is being displayed on a rail cart and has a log in its mouth to keep it open

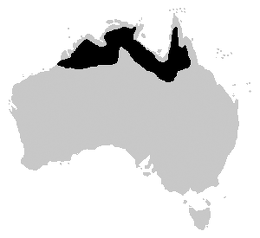

Australia has two kinds of crocodile: "freshies" — freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstoni) — and "salties" — saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). The latter can get very large and is responsible for most attacks on humans. Both are usually found in northern Australia. Their range overlaps somewhat, and sometimes the far more aggressive salties eat freshies

Ilsa Sharp wrote in “CultureShock! Australia”: If travelling the land, particularly in northern Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland, you should be careful when approaching coastal inlets, swamps and even large rivers quite far inland. In fact, frankly if I were you, I would never ever try to swim anywhere in such areas. [Source: Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Australia”, Marshall Cavendish, 2009]

If you are camping near such a spot, I am told it may be advisable to move camp every so often and generally, never to do the same thing twice in the same place at the same time of day. The crocodile apparently is quite cunning and may stalk you for several days to determine your habits before he strikes. The next time you go down to the billabong (oxbow lakes or backwaters or stagnant pools produced by floods) to fill your kettle for tea, at 5:00 pm, the same time as you always do, could be your last. Better still, don’t go near the water’s edge at all, not to get water, not to wash vegetables, not to wash yourself. Yes, they are that dangerous and you probably won’t see them until they hit you.

Global warming may be impacting crocodiles in Australia. Nesting periods, sex determination and the running and swimming speed of a hatchling are environmentally determined and influenced by temperatures and changes in temperature. While currently crocodiless in Australia are mostly found in northern parts of Australia, higher air and water could drive them further south.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CROCODILE CULTURE AUSTRALIA: URBAN CROCS, ABORIGINALS, DUNDEE, STEVE IRWIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

NEW GUINEA CROCODILES: TWO SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SALTWATER CROCODILES factsanddetails.com

CROCODILES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, DIFFERENCES WITH ALLIGATORS factsanddetails.com

PREHISTORIC CROCODILES: EVOLUTION, EARLIEST SPECIES, TRAITS factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE BEHAVIOR: COMMUNICATION, FEEDING, MATING factsanddetails.com

CROCODILES AND HUMANS: WORSHIP, THREATS, HANDBAGS factsanddetails.com

HOW TO CATCH A CROCODILE factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE ATTACKS IN AUSTRALIA: HOW, WHERE, WHY, DETAILS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE ATTACKS IN NORTHERN TERRITORY AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

SURVIVING CROCODILE ATTACKS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CROCODILE ATTACKS IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

SPECIES OF CROCODILES IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

Prehistoric Crocodiles in Australia

The fossilised remains of a 40-million-year-old crocodile were unearthed in central Queensland, scientists announced in 2005. eastern Australia. Al Jazeera reported: Monash University researcher Lucas Buchanan was the first to identify the fossilised remains, which were unearthed by a mining company in a lakebed at Gladstone. The almost complete skulls, one lower jaw, and parts of the legs, ribs and claws of two of the crocodiles have excited scientists studying the evolution of one of Australia’s more dangerous killers, still numerous across the country’s tropical north. “It’s important because it belongs to the earliest known genus of what’s called Mekosuchinae — a big group of extinct crocodiles that dominated Australia and developed a large degree of diversity,” Lucas Buchanan said. Buchanan said the new species of crocodile was very similar to the modern-day freshwater crocodile, suggesting the modern crocodile had changed little in millions of years of evolution. “The Queensland site has provided the richest and most plentiful supply of crocodile fossils from this time in history,” he said. [Source: Al Jazeera, 24 Feb 2005]

In June 2021, in a paper published in the journal Scientific Reports, announced the discovery of a new species of crocodile that was determined to be seven meters (23 feet) long, based on a piece of its skull, and lived between two and five million years ago. Alex Fox wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Australia hosted super-sized crocs millions of years ago. Researchers studying fossils found in southeast Queensland in the 19th century have discovered a new species of ancient crocodile that was slightly longer than the biggest confirmed saltwater crocodiles but still well shy of the 40-foot extinct croc Sarcosuchus imperator. [Source: Alex Fox, Smithsonian magazine, June 18, 2021

The new Australian crocodile has been dubbed Gunggamarandu maunala, a name that incorporates words from the Barunggam and Waka Waka Indigenous languages spoken near where the fossil was found and translates to “hole-headed river boss.”The team arrived at their estimate of Gunggamarandu maunala’s size by first extrapolating the probable size of its skull, which they say probably measured at least two and a half feet long. The giant reptile is the largest extinct crocodilian ever found in Australia, write study authors Jogo Ristevski and Steven W. Salisbury, Queensland University paleontologists, in the Conversation. "We also had the skull CT-scanned, and from that we were able to digitally reconstruct the brain cavity, which helped us unravel additional details about its anatomy,” says Ristevski in a statement.

Wakka Wakka elder Adrian Beattie tells Lucy Robinson of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC News) that the discovery is significant to the local Aboriginal community. "It's astounding," Beattie tells ABC News. “I'm picturing him now, one hell of a big crocodile. He'd be certainly something to respect."Ristevski also tells ABC News that based on what they can see of its anatomy, Gunggamarandu maunala is part of a group of slender-snouted crocodiles called the tomistomines that had previously never been found in Australia. "Prior to our study tomistomine fossils had been discovered on every continent except Antarctica and Australia," Ristevski tells ABC News. "But now we have proved that tomistomines were here as well."

Tomistomines are called “false gharials” because they have a skinny set of jaws that resembles the fish-catching chompers of the gharial. This group has many extinct members but only one living representative, the Malaysian false gharial. The tominstomines appeared some 50 million years ago, according to the Conversation. Their range was very widespread, with remains found on every continent except Antarctica.

It’s unclear what caused this lineage to go extinct in Australia, but Salisbury tells the Guardian that “it’s very likely related to the gradual drying of the Australian continent over the last few million years, and in particular over the last few 100,000 years. The big river systems that once supported crocs like this have long since dried up from south-east Queensland, and with them so have the crocs.”

Saltwater Crocodiles

Saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) are the world’s largest reptiles and predators that lives on land. They are larger than all mammalian land predators, including tigers, lions and bears and are arguably the most dangerous of all 28 species of crocodilian species. They can exceed six meters in length and can live up to 100 years. According to Mike Osborn, a real-life Crocodile Dundee and outback guide, they "can weigh as much as a four-wheel drive truck... Once they get past fourteen feet they suddenly broaden out, double in size...You wouldn't believe how massive they are. Once they've got you in their death roll. You're finished." [Source: David Doubilet, National Geographic, June 1996]

Saltwater crocodiles are thriving in northern Australia, s, particularly in the multiple river systems near Darwin such as the Adelaide, Mary, and Daly Rivers, along with their adjacent billabongs and estuaries. The saltwater crocodile population in Australia is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000 adults. They range from Broome, Western Australia through the entire Northern Territory coast all the way south to Gladstone, Queensland. [Source: Wikipedia]

Because of their ability to swim long distances at sea, individual saltwater crocodiles appeared occasionally in areas far away from their general range, up to Fiji. Saltwater crocodiles generally spend the tropical wet season in freshwater swamps and rivers, moving downstream to estuaries in the dry season. Crocodiles compete fiercely with each other for territory, with dominant males in particular occupying the most eligible stretches of freshwater creeks and streams. Junior crocodiles are thus forced into marginal river systems and sometimes into the ocean. This explains the large distribution of the species, as well as its being found in the odd places. Like all crocodiles, they can survive for prolonged periods in only warm temperatures, and crocodiles seasonally vacate parts of Australia when prolonged cold weather occurs.

See Separate Article: SALTWATER CROCODILES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Krys — the Largest Crocodile in Australia — and the Woman Who Shot It

Krys was the largest crocodile ever shot or captured in Australia. The saltwater crocodile was 8.63 meters (28.3 feet) long and was shot in July 1957 by Krys Pawlowski, a 30-year-old woman from Poland, on the MacArthur Bank of the Norman River. In Henry Park adjacent to the Shire Council Offices, in Normanton in northwest Queensland you can see a life-size replica Krys, affectionately nicknamed 'Krys the Savannah King'.

Krystyna 'Krys' Pawlowski had only been crocodile hunting for two years when she shot the 8.6-meter monster in 1957 and became famous afterwards. Outback folklore remembers her as "One Shot Krys" — the north Queensland hunter and taxidermist who shot 5000 crocodiles and missed only three. She lived outside Mareeba, west of Cairns, with another celebrated hunter, her husband Ron. By the 1980s, Pawlowski had become a conservationist rather than a hunter and said if she had to do it all over again she ould not have shot the giant crocodile. "I was really sorry I shot him, poor fellow," she said. "He never woke up, he didn't know we were there. We couldn't move him, he was too big. He was the most beautiful animal," Krys said.

Ndaman wrote in Opera News: “Hunters had tried to get this croc for decades and were astounded that a 'lady' did what no man could. Her shot made her family famous. Krys's famous croc-hunting career started in 1955 in Kaumba, in Queensland's Gulf Country when a 12-foot reptile started creeping up on her three-year-old daughter, Barbara. 'My brother came out and saw it and yelled "Barbara, crocodile!" and my father grabbed a rifle and shot it between the eyes,' Krys's son George Pawlowski told Daily Mail Australia. [Source: Ndaman, Opera News, 2021]

The Polish immigrants, who came to Australia in 1949 and had been struggling to get by, realised they'd struck gold when they took the beast to be skinned An old-timer in the town helped us skin the crocodile and we sent it off to a dealer in Brisbane and finished off getting 10 pounds for it,' Mr Pawlowski said. 'In those days 13 pounds was the basic weekly wage, so Dad (Ron Pawlowski) thought they were on to something.' Krys would go to find fame as 'One Shot', the petite 5'4'' crocodile hunter who would kill up to 10,000 reptiles over a 15-year hunting career with her husband — all while wearing long beautifully-manicured red nails.

Legend had it the mother-of-three only missed three shots in her lifetime and was able to hit a moving crocodile with ease — despite having never fired a rifle before she arrived in Australia just six years before her famous crocodile kill. She was also able to skin the reptiles faster than anyone else, and she would usually do it right after the kill — on the spot amid the mangroves and mosquitoes. She was better than me with a pistol and she was much better with a rifle at moving targets from a boat,' Ron once told reporters. 'We both could hit a bottle top at 100 yards, but Krys could shoot through the same hole the second time.' After taking the 8.6-meter monster down, Ron built a small boat out of scraps and called it 'Joey' and the family started their new lives as crocodile hunters.

Freshwater Crocodiles

Freshwater crocodiles(Crocodylus johnsoni) are also known as Johnson's crocs, Australian freshwater crocodiles, Johnstone's crocodiles, and freshies. A species of crocodile native to the northern regions of Australia mostly in the Northern Territory and Queensland, but also in northwestern Australia. They occupy various fresh water areas such as lagoons, rivers, swamps and billabongs (oxbow lakes or backwaters or stagnant pools produced by floods).Freshwater crocodiles are smaller, less aggressive and gentler than saltwater crocodiles. They are not known as man-eaters and seldom threaten humans. They do bite in self-defence, and brief, nonfatal attacks have occurred, apparently the result of mistaken identity. Children in particular have been targets.[Source: Wikipedia, Nikoma Boice, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Freshwater crocodiles are relatively small crocodilians. Males can reach a length of 2.3 to 3 meters (7.5 to 9.8 feet), , including tail, although individuals of four meters (13 feet) in length have been reported in the Lake Argyle and Katherine Gorge areas. Females top out at 2.1 meters (6.9 feet). Males commonly average around 70 kilograms (150 pouns), with large one weighing up to 100 kilograms (220 pounds) while females on average weigh around 40 kilograms (88 pounds).

Freshwater crocodiles have much narrower snouts and smaller teeth than more dangerous saltwater crocodiles. Their body color is light brown with darker bands on the body and tail. These bands tend to be broken up near the neck. Some individuals possess distinct bands or speckling on the snout. Body scales are relatively large, with wide, close-knit, armoured plates on the back. Rounded, pebbly scales cover the flanks and outsides of the legs. Freshwater crocodiles have approximately 68 to 72 teeth total with five premaxilla teeth, 14-16 maxilla (upper jaw bone) teeth, and 15 mandibular teeth.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Freshwater crocodiles are listed as a species of least concern. They have been hunted in the past by Aboriginals and Europeans for meat, eggs, and their leather-producing hide. Aboriginal hunting did not significantly affect the population. In the late 1950s, tanning processes made it possible to substitute the skins of this species, instead of those of the preferred saltwater crocodile to be used in leathermaking. Hunting did cause a decrease in populaton size but protective measures were taken in the early 1960s. They have been protected by law in Western Australia since 1962, and in the Northern Territory since 1964 . Queensland did not pass its protective laws until 1974. Illegal hunting continues. The main threats are habitat loss and degradation. Small scale ranching and farming of these crocodiles exists. |=|

Freshwater Crocodile Behavior, Diet and Reproduction

Freshwater crocodiles are shy, ambush hunters. They eat variety of invertebrate and vertebrates, including crustaceans, insects, spiders, fish, frogs, turtles, snakes, birds, and various mammals. Insects appear to be the most common food, followed by fish. Large individuals may consume terrestrial prey. When hunting, these animals use a sit-and-wait method in which the crocodile lies motionless in shallow water and waits for fish and insects to come within close range, before they are snapped up in a sideways action. However, larger prey such as wallabies and water birds may be stalked and ambushed in a manner similar to that of the saltwater crocodile. A freshwater crocodile was filmed being eaten by an olive python. It reportedly succumbed after a struggle of around five hours. [Source: Wikipedia, Nikoma Boice, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Freshwater crocodiles are saltwater tolerant but are generally outcompeted by saltwater crocodiles and are preyed upon by them. Freshwater crocodiles can live in areas where saltwater crocodiles cannot such as areas above the escarpment in Kakadu National Park and in very arid and rocky conditions such as Katherine Gorge, where they are common and are relatively safe from saltwater crocodiles during the dry season. However, they are still consistently found in low-level billabongs, living alongside the saltwater crocodiles near the tidal reaches of rivers.

Females freshwater crocodiles nest in holes that are exposed on sandbars during the dry season from August through September. Mating occurs three to six weeks before laying. Clutches average in size between 13 and 20 eggs and hatch in about 65-95 days. Egg laying usually occurs at night. Eggs are preyed upon by monitor lizards and feral pigs. High and low temperatures (33-34̊C, 91-93.2̊F) produce female embryos while intermediate temperatures (32̊C, 89.6̊F) produces male embryos. The nests of eggs are left unguarded, but the mothers reappear in late October. At the end of the incubation period, mothers carry newly hatched young to the water in their mouths. The mothers then stay close to the young and protect them for a short period of time. In addition to being hole nesters, they are also sometimes called "pulse nesters" because all females in a given population nest within a brief three week period each season. Individuals reach reproductive maturity when they reach 1.5 meters in length.

Dwarf Crocodiles — A Separate Species?

Dwarf crocodiles, also known as pygmy or "stunted" crocodiles. Males grow to a maximum of 1.7 meters (five foot six inches), and females only reach 0.7 meters (two foot three inches). They are are half the size of other freshwater crocs. Dwarf crocodiles are thought to be stunted due to a lack of available food. There is no evidence that the rare pygmy is genetically different to other freshwater crocodiles.[Source: AFP, July 3, 2013]

There are no recognized subspecies of freshwater crocodiles in Australia although darker-colored dwarf specimens have been identified in the Northern Territories. There are some who think they should be recognized as separate species even though there is no scientific evidence to back up the claim. Fred McCue wrote in the Northern Territories News, “Melbourne reptile expert Raymond Hoser claims he has finally been vindicated in his claim that the Top End’s pygmy crocodiles are a separate species to what he refers to as the “bog standard” freshie. Mr Hoser is also demanding an apology from Top End crocodile experts who he claims have “publicly lampooned” him in the past. But the Top Enders are unmoved. They say Mr Hoser’s claims are a total crock and science is on their side. [Source: Fred McCUE,Northern Territories News, November 19, 2014]

Zoologist Dr Adam Britton with a dwarf crocodile in the Northern Territory, photo from Charles Darwin University

The pygmy, or dwarf crocodiles were discovered in the mid-1980s. There are only a few hundred living in clusters in the Liverpool River in Arnhem Land and Bullo River, near the West Australian border. Mr Hoser has seized on a report on ABC Radio, quoting Charles Darwin University crocodile researcher Dr Adam Britton, to support his latest demand for new species status. “He’s quite wrong about that,” Dr Britton said. “We’ve done the genetics and we can safely say these are Australian freshwater crocodiles and they are not a separate species. “Raymond Hoser just wants to name them.”

Mr Hoser has previously attempted to have the Top End’s pygmy crocodiles named after his daughter Jacky. He wants them recognised as Oopholis jackyhoserae rather than Crocodylus johnstoni. Chief scientist at Darwin’s Crocodylus Park, Charlie Manolis, said DNA evidence was against Mr Hoser and so was the view of the Crocodile Specialist Group, 500 of the world’s leading experts.

Dwarf Crocodiles Feed on Poisonous Cane Toad By Eating Only Their Back Legs

Emilia Terzon reported on ABC Radio Darwin: In 2006, researchers were excited to confirm a new cluster of dwarf crocodiles near Bullo River, about 11 hours' drive south of Darwin. After an infestation of cane toads moved into the river in 2008, there were grave concerns for the small crocodiles' survival. The introduced American cane toad has toxic glands in its shoulders, eyes, ovaries and eggs. Charles Darwin University crocodile researcher, Dr Adam Britton, said the notorious pest presented a "toxic prey" for the rare reptiles. "If these crocodiles...grab [the cane toads] in their mouths and bite down into their toxin glands, they get enough toxin to kill them," he said. [Source: Emilia Terzon, ABC Radio Darwin, November 17, 2014]

One year after the cane toads arrived, Dr Britton and his partner recorded a 75 per cent drop in the Bullo River crocodile population. "We were worried that they were completely going to disappear," Dr Britton said. Yet they were also intrigued to discover the bodies of some unusually dismembered toads near the river. "[My partner] found a large number of toads with twisted back legs and they had little teeth marks on them," he said.

There are no toxins in the hind legs of cane toads, meaning this part of its body is able to be consumed. The nibbled cane toad bodies were therefore a hopeful sign that the dwarf crocodiles were figuring out how to safely eat their prey. "If any crocodile actually seizes a toad by its back legs and successfully rips them off and eats them, it's going to learn that it can get a meal without being poisoned. "They were learning and adapting to this toxic prey."

Last month, the team once again surveyed the area and found more dead cane toads with either whole or partial missing back legs. They also found dwarf crocodiles in areas from which they had previously disappeared, adding weight to the team's cane toad adaptation theory. "It's pretty conclusive that's what is going on," Dr Britton said.

Return of Large Crocodiles in Australia

Nick Squires and Catriona Davies wrote in The Telegraph: Crocodiles were once considered an endangered species in Australia, where hunting took them to the brink of extinction. But since hunting them was banned 30 years ago, the problem has swung the other way and an explosion in numbers is causing a headache for farmers who are losing livestock in crocodile attacks. Conservationists estimate that the Northern Territory's population of wild saltwater crocodiles, which are larger and more aggressive than their freshwater cousins, has grown from 5,000 in the early Seventies to 70,000 today. The saltwater crocodiles, which can grow up to 18 foot long and are among the world's most dangerous reptiles, have begun to supplement their usual diet of fish, wallabies and turtles with cattle, horses and dogs. Crocodiles lie in wait, almost submerged, before launching themselves at an animal close to the water's edge. [Source: Nick Squires and Catriona Davies, The Telegraph, October 27, 2003]

Before the ban on hunting, crocodile hides were big business. In the 15 years before 1972, it is estimated that 270,000 saltwater crocodile hides and up to 300,000 freshwater hides were exported to Europe. The hunters shot their way out of the market, as there were so few crocodiles remaining by the late Sixties that most hunters could not make a living. This led to a government ban in Western Australia in 1969, followed by the Northern Territory in 1971 and Queensland in 1974. The explosion in numbers that followed has sparked a public debate over whether crocodiles should be more extensively culled.

The Northern Territory government has investigated ways of allowing sustainable harvesting of crocodiles, to give an incentive for the preservation of the animals and their habitat. One such programme allows the controlled collection of eggs from wild nests, which are then sold to crocodile farms for skin and meat production. In 1997, the Northern Territory government started a trial, allowing Aboriginal communities to harvest adult wild crocodiles — the first time hunting had been carried out legally in 26 years. "Whenever there's an attack there's a public outcry, with people saying 'let's get rid of them'," said Dion Wedd, the acting curator at the Territory Wildlife Park, south of Darwin. "There are certainly more of them and they are becoming less fearful of boats and the sound of outboard engines. But it all comes down to personal responsibility — if you go swimming in a river and get attacked by a croc, that's your lookout."

Across the border in Western Australia, a former crocodile catcher and fishing safari guide, Jane Harman, 46, has also noticed a growth in the population. "They are definitely increasing because they are no longer being hunted," she said. "When you get up close to a 15-foot croc, it's pretty impressive. It's the head and the eyes that I find the most fearsome, especially if they are chewing on a dead cow. We have one which hangs around our fishing camp. He's popular with the tourists." There have also been crocodile attacks on humans, although these are rare. In October last year a German tourist was killed by a 15ft-long saltwater crocodile while taking a midnight dip in a billabong in Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory.

Large Crocodiles Taking Cattle and Stalking

Nick Squires and Catriona Davies wrote in The Telegraph in 2003: One outback farm is reported to have lost 200 cattle in a year to crocodile attacks, and another five dogs, the most recent taken on a riverbank just 500 yards from the owner's house. As the wet season in the Northern Territory approaches, the crocodiles are becoming even more active. Next month, the temperature will rise to an average high of 92F (33C), small creeks will turn into raging rivers and billabongs (oxbow lakes or backwaters or stagnant pools produced by floods). become large lakes, allowing the crocodiles to spread out over a greater area. Marlee Ranacher, 42, and her husband Franz, 34, have 9,000 cattle on their ranch covering 500,000 acres at Bullo River Station, 240 miles southwest of Darwin. [Source: Nick Squires and Catriona Davies, The Telegraph, October 27, 2003]

"When I grew up on the property a 12-foot crocodile was considered big. Now we are regularly seeing 16-footers and some are up to 18 feet. At that size they weigh a ton," said Mrs Ranacher. "We have a creek close to the house and when it floods the crocodiles come right up to the back gate. We have 140 miles of crocodile-infested river bank on the property." Mr and Mrs Ranacher have been given a licence by the Northern Territory Parks and Wildlife Commission to trap and shoot 10 large crocodiles. The animals' skins, complete with skull, sell for as much as £6,000. A natural history museum in the United States has placed an order for an 18-foot "saltie", as saltwater crocodiles are known.

In 2024, there were reports that a 4.4-meter (14-foot) saltwater crocodile was “lingering around the private property and stalking domestic and farmed animals,”in Cordelia, Queensland, wildlife official at the Queensland Department of Environment, Science and Innovation said. Officials investigated and designated the crocodile as a “dangerous animal” but had a hard time catching it. First, “we tried an in-river floating trap but due to the amount of rainfall and elevated river levels” the trap didn’t work, Tony Frisby, a senior wildlife officer with the department, said in the release. Instead, “we had to install a gated trap, which is a trap that rests on the riverbank,” Frisby said. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, April 4, 2024]

Aspen Pflughoeft wrote in the Miami Herald, After weeks of evading capture, the 14-foot-long crocodile finally fell for the trap, officials said. A second large crocodile, measuring about 10 feet in length, was also captured in the nearby Townsville area. Both crocodiles will be kept in captivity, either at crocodile farms or zoos, the department said. Cordelia, Queensland, is about 1,400 miles northwest from Sydney and along the country’s northeastern coast.

Crocodile Leaps from River to Snatch a Flying Bat in the Air

David Strege wrote in FTW Outdoors: As dozens of bats swooped down to collect water from the Daintree River in Australia, one crocodile awaited the perfect opportunity to pounce and with “unbelievable precision” leaped up from the water and snatched a bat in midair.David White, owner of Solar Whisper Daintree River Crocodile and Wildlife Cruises in Queensland, captured the moment in video shot with a backup camera. “Sorry about the quality,” he writes on Facebook, “but the content…you just don’t see this every day.” [Source: David Strege, FTW Outdoors, March 11, 2022]

“So after watching these guys for 25 years they are still full of surprises,” White wrote. “Many of you may of seen footage of freshies (freshwater crocs) catching little reds in the NT. Well, where that happens the river is narrow and there are hundreds of thousands of little reds. Not so here, this is a very wide river and there’s not many bats in comparison to when the little reds are here. Though I have seen bats eaten before, it’s when they fall into the river.

“But take a moment to appreciate the skill involved here by Dusty Rose. She had to work out where to place herself in this wide river and usually she hunts on the edge, then with unbelievable precision she jumps. “Over the years I have talked to many scientists and I agreed with them that this river is far too wide for the crocs to be successful in catching a bat. Well boy was I wrong.”

Sharks Versus Crocodiles in Australian Waters

While night fishing off the coast of Australia’s Wessel Islands, a group witnessed an intense battle between a group of sharks and a crocodile. Jessie Leigha, professional angler with Wildcard Luxury Cruises, took video of the “unfriendly nighttime guests” and posted it Instagram on November 29, 2023. The Miami Herald reported: Her videoshows a large number of sharks swimming around the fishing boat. ”We had anchored up for the night in a bay and the sharks were in full form at the back of the boat, so we were watching them for a bit,” Leigha told McClatchy News via Instagram. “It is very common to have this many sharks off the back of the boat.” Then the crocodile appeared. “We were all shocked as I have never seen both (animals) together before,” Leigha said. The Wessel Islands are an island chain along the northern coast of Australia, about 1,800 miles northwest of Sydney. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, December 5, 2023]

Video shows the crocodile swimming near the boat and its rope. As it tries to bite the rope, several people yell at the animal to let go. The sharks continue circling the crocodile, then one attacks from below, biting the crocodile’s neck, the video shows. A wild splashing ensues. Fishermen can be heard yelling in shock and surprise. The croc then surfaces further away from the boat, as the video ends with the crocodile swimming off “The sharks had a few chomps on Mr. Snappy,” Leigha wrote on Instagram. “It was absolutely amazing and crazy,” Leigha told McClatchy News. “We have never seen this form of interaction before and a lot of us have been at sea for many many years.” “The sharks didn’t like (the crocodile) in their waters,” Leigha told the Australian outlet 7News. “They’re not used to it and maybe saw (the crocodile) as a contender for food.” Leigha told McClatchy News that the crocodile survived and was later seen in “fine form” on a beach.

A wild video posted in December 2024, shows shark feasting on a fairly large, dead crocodile on Australian beach, USA TODAY reported: Alice Bedwell told newswire Storyful that she was at Town Beach, located in Nhulunbuy, on December 13 when she recorded the dramatic encounter. The beginning of the footage shows a medium-sized crocodile with an impressive tail lying belly-up in the surf. Waves lap its head, which rests in the water, as its two front feet remain turned toward the sky. To its immediate right, a large shark slowly swims up to the reptile. In an instant, the predator snaps up the croc's head. Thrashing ensues, with the shark apparently chowing down on the crocodile in the process. Eventually, both disappear beneath the surface. [Source: Natalie Neysa Alund, USA TODAY, December 18, 2024]

A clip posted by Auswide Explorers, featuring the Stevens family, shows a shark prowling around as a crocodile attacks sea turtle near a surf camp at Dundee Beach in the Northern Territory of Austalia. The Stevens family captioned: “Can't get more Australian... A crocodile eating a turtle and being stalked by a shark...This happened over a month ago right in front of our camp at Dundee Beach...A good reminder not to go swimming at the beach in the Northern Territory. [Source: Dashel Pierson, SURFER Magazine, October 14, 2023]

Managing Crocodiles in Australia

Freshwater crocodiles have been protected from hunting in the Northern Territory of since 1874. Salties, since 1971. Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Aboriginal people have traditionally hunted crocodiles for their meat, but the animal’s population remained stable until World War II ended and high-powered rifles became widely available. Commercial hunters and trigger-happy sportsmen slaughtered them indiscriminately. Since given protection in Australia during the early 1970s, their numbers have rebounded, then boomed to about 100,000. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, March 2015]

Moving salties from one place to another, a practice known as translocation, has been used in Queensland to manage potential safety risks posed by the animals. “Our experiment showed that translocation was ineffective and extremely dangerous,” Franklin says. Residents and tourists got a false sense that the waters were crocodile-free. The government abandoned its program in 2011.

“Though hunting salties is banned in Queensland, the state has established “Crocodile Management Zones.” Private contractors have been enlisted to capture, snare or harpoon rogue salties in those areas: “All crocodiles removed from the wild are placed in a zoo or crocodile farm or, in some cases, humanely euthanized,” according to the 2013 Hinchinbrook Shire Council Saltwater Crocodile Management Plan. Franklin says, “Some have regrettably died during their capture by the government, which is something that has never occurred during our research.”

“Bindi Irwin considers the plan unconscionable. “Crocodiles are of vital importance,” she says. “They’re apex predators that regulate populations of other organisms. Without them, the entire ecosystem could collapse.” Sure, she concedes, crocodiles can, and sometimes do, attack and kill people. “But they’re not after people,” insists the Jungle Girl. When humans are attacked, she reasons, it’s almost always because they acted irresponsibly: fishing with bait tied to their belt, swimming after dark, ignoring warning signs or stealing them for souvenirs. “It’s up to us to learn to live with crocs,” she says. “After all, they were here first.”

Crocodile Farming in Australia

Laura Baisas wrote in Popular Science: According to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Australia, crocodiles have been farmed to produce luxury goods like handbags and belts, as well as for their meat in Australia’s Northern Territory since the late 1970s, partially as a response to decades of overhunting. Government approval is given to businesses to harvest up to 100,000 eggs total from the wild annually in the country’s Northern Territory. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, Jun 27, 2023]

While croc farming is not officially banned, it does come with ethical concerns. Confinement and crowded conditions from breeding can lead to stress in the animals due to lack of space to move, eat, and interact with other animals. The Australian Government has issued a Code of Practice for the humane treatment of the crocodiles and it is illegal to capture or farm wild crocodiles in the state of Queensland. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) Australia still continues to stand against crocodile farming, with Australian supermodel Robyn Lawley speaking out on PETA’s behalf against the use of crocodile farms in the luxury fashion industry.

Saltwater crocodiles were on the brink of extinction in the early 1970s due to hunting. Salties are now a protected but vulnerable species with roughly 20,000 to 30,000 in Queensland. In the Northern Territory, they are no longer considered a conservation concern.

Some conservationists, including crocodile expert Grahame Webb, attribute placing economic value on crocodiles as part of the solution to bringing sustainable benefits to the Northern Territory and conserving crocs. “Croc farming promotes sustainable practices and has played a pivotal role in returning saltwater crocs from the brink of extinction in recent times. By placing an economic value on crocodiles, communities living with or near crocs are more tolerant of their presence and are encouraged to protect their habitats,” says Hall. “Protecting the viability of this industry also benefits other species that co-inhabit with crocs eg. brolga, jabiru and long-necked turtle.”

Crocodile Harvesting in Australia

Carmor Plains and Australia Wide Safaris are one of the few safari operators offering Crocodile harvesting. According to them: We have a license to catch and shoot saltwater crocodiles for their skins and skulls as trophies. Whilst it is prohibited for our guests to actually shoot the crocs themselves, you can observe us catching them. You can then arrange to purchase the skin or skull from us. [Source: Australia Wide Safaris — Carmor Plains Wildlife Reserve]

Firstly a large croc must be located. This is done by looking for tracks or slides around a waterhole or creek. Partly eaten animals or a pile of bones, normally wallabies and wild pigs (or buffalo if it is a big one!) are always good sign. Then we place the trap in shallow water or on the bank directly by the water. Then an animal carcass (normally a wild pig) is placed in the trap with a rope attached to work as a trip wire. The croc takes the bait, the gate shuts! Bingo!!

This can be achieved in no more than two days, but we usually suggest four or 5. We will not harvest a crocodile smaller than three meters (10 feet). We prefer to only harvest the male crocs and this size limit ensures that very few females are actually taken. If a smaller croc is caught it is simply released. This in itself is quite an exciting event as the crocs often turn the tables upon release and the hunter becomes the hunted!

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025