Home | Category: Marsupials

NORTHERN HAIRY-NOSED WOMBATS

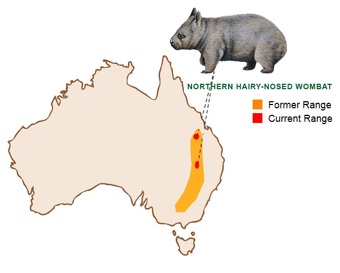

Northern hairy-nosed wombats (Lasiorhinus krefftii) are the largest wombat species, one of the world's largest burrowing animals. and the most endangered marsupial. Their range once extended across a large swath of New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland, and as recently as 100 years ago it was considered extinct mainly as a result of the rapid introduction of sheep, cattle and rabbits into their range by European settlers in the 19th century and the competition of these animals with the wombats for grass, especially during droughts, which are where northern hairy-nosed wombats live. In the 1930s a population of about 30 individuals was discovered in a three-square-kilometers(1.2-square-mile) area within the 32-square-kilometers (12-square-mile) Epping Forest National Park in Queensland. [Source: Wombat Foundation =]

Northern hairy-nosed wombats are heavily built and range in weight from 25 to 40 kilograms (55 to 88 pounds), averaging 32 kilograms (70.4 pounds). Their thick, stocky body averages about one meter (3.25 feet) in length. Females are larger than males These wombats have very powerful forearms, large heads, small eyes and pointed ears. They have soft, silky brown fur, and long whiskers extending from the sides of their noses — the source of their name. Like other wombats, females have rear-oriented pouches and some continuously-growing rodent-like teeth [Source: Megan Schober, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The only known wild populations of northern hairy-nosed wombats are in three locations in Queensland: 1) the Epping Forest National Park, northwest of Clermont in Central Queensland; and 2) a smaller colony Richard Underwood Nature Refuge at Yarran Downs; and 3) a new colony in Powrunna State Forest, south west Queensland. . The Richard Underwood colony was established by translocating wombats and was created through the Xstrata reintroduction project, funded by Xstrata, a Swiss global mining company. In June 2024, 15 wombats were translocated to Powrunna.

[Source: Wikipedia]

Northern hairy-nosed wombats live in semi-arid open woodlands and grasslands in an area with little water and rain and winter temperatures can fall below 0 degrees celsius and summer temperatures regularly exceed 40 degrees celsius.. They prefer semi-arid grasslands on sandy soil which is suitable for burrowing and require a year-round supply of grass, which is their primary food source. Not all soils are suitable for northern hairy-nosed wombats to dig their burrows. In Epping Forest National Park (Scientific), they dig their burrows in the deep, sandy soils along ancient dry creek beds. They forage in areas of heavy clay soils adjacent to the sandy soils, but do not dig burrows in the clay soils, which become water-logged in the wet seasons. At Epping Forest National Park (Scientific), burrows are often associated with native bauhina trees, Lysiphyllum hookeri. This tree has a spreading growth form and it roots probably provide stability for the extensive burrows dug by northern hairy-nosed wombats. [Source: Queensland government]

The oldest wild northern hairy-nosed wombat was at least 23 years old. A northern hairy-nosed wombat in captivity lived to be more than 30 years old. One very interesting thing about this species is their loss of heterozygosity ( possession of two different forms of a particular gene). Measurements of DNA variability made on DNA extracted from specimens from extinct populations of northern hairy-nosed wombat this wombat in Deniliquin, New South Wales revealed that Epping Forest populations have only 41 percent of the variability of the extinct population, suggesting a bottlenecked species in steady decline. |=|

RELATED ARTICLES:

WOMBATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

WOMBAT SPECIES: COMMON (BARE-NOSED) AND HAIRY-NOSED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WHEN, WHERE AND HOW THEY LIVED AND WENT EXTINCT ioa.factsanddetails.com

GIANT ICE-AGE ANIMALS IN AUSTRALIA: WOMBATS, KANGAROOS AND THUNDER BIRDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Endangered Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombat

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, northern hairy-nosed wombats were listed as Critically Endangered, the group’s most dire ranking, just short of being extinct. The northern hairy-nosed wombat is also critically endangered species under Queensland's Nature Conservation Act of 1992 and the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act of 1999. The biggest threats the species faces are its small population size and limited range, predation by wild dogs, competition for food because of overgrazing by cattle and sheep, and disease. Improved conservation measures led to growth in wombat numbers but predation continued to be a problem, with 10 percent of the population killed in wild dog attacks in 2000-2001. The small population size and limited ranges of northern hairy-nosed wombats makes them vulnerable to local catastrophic events such as disease, wildfire and severe drought, and makes inbreeding and the subsequent loss of genetic variation more likely.

In the 1980s, just 35 of these wombats were counted in a survey. In the 1990s, only around 65 of these wombats, with perhaps 15 breeding females, remained in a single colony in Epping Forest National Park. In 2003, the total population consisted of 113 individuals, including around 30 breeding females. After recording an estimated 230 individuals in 2015, the number was up to over 300 by 2021, and over 400 by 2024.

Northern hairy-nosed wombats were hunted in the past for their fur, which had some commercial value, but are believed to have become endangered primarily as a consequence of competition from livestock and introduced animals like rabbits. There were populations of Northern hairy-nosed wombats near St. George in South Queensland and near Jeriderie in New South Wales until around 1910.

Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombat Conservation

Today, all northern hairy-nosed wombats are protected. Efforts to help them have included the construction of a 20-kilometers dingo-proof fence around all wombat habitat at Epping Forest National Park in 2002 after the wild dog attacks in 2000-2001. Since the erection of a predator-proof fence and provision of supplementary feed and water, numbers have grown significantly. The long-term vision of the Wombat 2022 Recovery Action Plan is to improve the species’ conservation status primarily by increasing the size of existing sub-populations and the number of sub-populations. The vision is: “By 2041, there are multiple ( more than four), viable wild sub-populations of NHW that are protected, effectively managed, and geographically spread.” [Source: Wombat Foundation =]

The conservation effort to save northern hairy-nosed wombats has not come without costs. In some cases cattle ranchers have been forced to find new areas for their cattle to graze. This is especially difficult because the area where the wombats live is plagued by droughts. Trapping and relocatding wombats has been a major tool used for conservationists to build up the population of wombats. The trapping experiments were begun in 1985. In the past cattle grazed in Epping Forest National Park here are now strict restrictions on cattle grazing in the park. Fences have been erected to prevent cattle incursions into the park. [Source: Megan Schober, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

In 2009, the first individuals were relocated to Richard Underwood Nature Refuge near St George in southern Queensland, reducing risk of extinction in the wild as a result of disease, fire or flood sweeping through a single population. However, the second population is probably too small to sustain a viable population of wombats. St George is one of the few locations where northern hairy-nosed wombats have been officially recorded in the pastThe wombats’ new home had been prepared for their arrival, complete with ready-made burrows, supplementary feed and water stations, and a fence to keep out predators.Five wombats made the move in 2009. They have since been joined by 10 other wombats from Epping Forest who were moved over the course of three transfers in 2010. [Source: Wombat Foundation]

After a long concerted effort, a third site was found at 2,800-hectare Powrunna State Forest, south west Queensland. In June 2024 the first 15 wombats were translocated from Epping Forest National Park to their new home where they are settling in well. Up to an additional 60 wombats will be moved to Powrunna in 2025 and 2026. The aim is to create a self-sustaining third population, with a fourth site aimed to be established by 2041 in part of the species’ former range. The more insurance populations that are established, the lesser the risk of extinction from predators, disease or disasters, ensuring the species continues to bounce back from the brink.

Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombat Behavior and Diet

Hairy-nosed wombats are hard to observe in the wild as they spend much of their time underground. They are fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), territorial (defend an area within the home range). They have a home range of approximately six hectares (15 acres). Although they are nocturnal feeders, they like to sunbathe close to their tunnel entrances early in the day. Northern hairy-nosed wombats have poor eyesight. Their strongest senses are smell and hearing. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW), Wombat Foundation]

Northern hairy-nosed wombats are generally solitary animals; however, they live in clusters of burrows that can be used by four to five wombats. Occasionally males and females are found together. Burrow sharing usually involves only with male and female interaction being restricted to breeding. This close association between individuals and overlapping feeding areas indicate some level of social organisation within the species. There was also evidence from Epping Forest National Park that wombats followed the trail or scent of other wombats, indicating they prefer to be in the presence of other wombats. [Source: Queensland government]

Hairy-nosed wombats are strictly herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and their diet is almost 100 percent grass. They feed on the native grasses in the park where they they reside, which include Hetropogon contortus (bunch spear grass) and Aristida spp. (three-awned grass). The wombat's decline in numbers has mostly been due to competition from local cattle for the grass they both feed upon. Northern hairy-nosed wombats spend an average of six hours above ground per night in the dry season and forage over a relatively small area of only about six hectares. Wet season feeding range size is halved and activity decreases to about two hours per night. In comparison, an eastern grey kangaroo needs to feed for about 18 hours a day.

Adult northern hairy-nosed wombats generally maintain good body condition year-round, as well as during droughts, due to their cool, humid burrows increasing the ability to conserve energy and water. This lower energetic requirement also means wombats spend relatively little time foraging. The area northern hairy-nosed wombat’s forage is larger during winter (dry season) than summer (wet season) due to lower food availability. Foraging areas are similar between males and females—approximately 27 hectares. Epping Forest National Park and Richard Underwood Nature Refuge are equipped with water stations, which are mainly visited by wombats in the dry seasons; although, not all northern hairy-nosed wombats use them. Supplementary food has been provided in extreme drought conditions.

Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombat Reproduction and Parenting

The breeding biology of the northern hairy-nosed wombat is thought to be similar to southern hairy-nosed wombats, with female northern hairy-nosed wombats likely to become sexually mature at about two and a half years old and males at about three years old. After a gestation period of 21 days, northern-hairy nosed wombats give birth to a single joey which is kept in the mother’s pouch for eight to nine months. The exact time young wombats spend with their mothers after permanent emergence from the pouch is unknown, but it's likely around one year.

At Epping Forest National Park most young emerge from the pouch in summer between November and April, when the availability of green grass is at its highest. Breeding success is heavily affected by rainfall, with reduced breeding rates recorded at Epping Forest National Park (Scientific) during the drought period in the early 1990s. Periods of higher than average rainfall at Epping Forest National Park have stimulated breeding success, with between 50 percent and 80 percent of females breeding in good years. This is most likely because rain makes the native grasses more abundant. [Source: Queensland government]

Hairy-nosed wombats may be monogamous and engage in seasonal breeding once a year . Most young are born in the wet season (November to April). Based in observations of southern hairy-nosed wombats, pouch life may range from eight to nine months, is followed by a three-to six-month period when the young initially remains in the burrow while the mother goes out to feed and then follows her when she is above ground. Weaning occurs around 12 months.

To avoid inbreeding, female northern hairy-nosed wombats usually undertake long-distance dispersal at least once in their lifetime. In most mammal species this is undertaken by young males. It is believed that female wombats do this to leave their burrow to their young which would find it hard to construct their own burrow.

Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombat Burrows

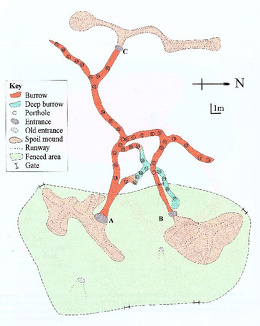

Northern hairy-nosed wombats are well-known for their burrow-building skills. Their large multi-entrance burrows can reach depths of nearly four meters and contain more than 100 meters of tunnels. They build their intricate tunnel systems (called warrens) in deep sand and often use the roots of trees as a "roof" for their larger tunnels. The largest burrow systems, containing warrens of several animals, may stretch over over a 300-hectare (750-acre) area. Most have multiple entrances that lead to single burrow complex. Individual wombats rarely use the same burrow simultaneously, but they do use burrows of previous generations. Most permanent northern hairy-nosed wombat burrows are constructed under large trees whose roots help provide stability for the burrow in the sandy soil that is typical of wombat habitat.

Burrows are arranged in groups which are used by four to five wombats. Adjacent burrows are connected by well worn paths and active burrows are regularly ‘sign-posted’ with dung and urine. Burrows are occupied by a single wombat 70 percent of the time. Burrow sharing may occur in the larger, multi-entrance burrows and usually involves females rather than a male and female. Although casual movements between burrow groups are rare, at least half of adult females change burrow groups at some time in their lives. This behaviour helps prevent inbreeding and is probably a form of maternal investment, whereby mothers leave their burrows to their young who would be too small to head off and construct their own. [Source: Wombat Foundation]

A northern hairy-nosed wombat burrow can be detected in the landscape by a mound of dug-out sand at the entrance, which can be more than one metre high and several metres long. A ‘runway’ passes through the mound and leads to the burrow entrance. Wombats dig the burrow with their forepaws, kicking the loose sand behind them. They then walk backwards out of their burrow to bulldoze the sand clear. A northern hairy-nosed wombat will mark the entrance and mound near its burrow with dung, splashes of urine and scratches. [Source: Queensland government]

Researchers at Epping Forest National Park have mapped several northern hairy-nosed wombat burrows. The largest mapped burrow contained more than 90 meters of tunnels and six entrances. Major burrows average 3 to 3.5 meters in depth with a diameter of less than half a metre, just enough for a wombat to pass.

Temperatures in the burrows are remarkably stable and do not vary more than 5–6°C each day. Even on cold winter nights when temperatures above ground drop below zero, burrow temperature will not drop below about 12°C. Stable burrow temperatures mean wombats can avoid extreme heat and cold conditions by only exiting their burrows when temperatures are favourable. Compared to above ground, humidity is higher in deep burrows. Breathing the moist air in burrows helps northern hairy-nosed wombats conserve moisture, even during the hot dry summer months.

Xstrata — the Swiss Mining Company Helping Northern Hairy-Nose Wombats

Xstrata, a Swiss global mining company valued at $28 billion in 2009 that merged with Glencore in 2013 to form Glencore Xstrata, has largely funded a recovery project for northern hairy-nose wombats. Todd Woody wrote in Time magazine: In exchange for spending millions on the marsupial, Xstrata's name will appear on everything wombat: from websites to educational DVDs to shirts worn by wildlife workers. Xstrata execs will also star in documentaries about the northern hairy-nose and speak at media events. Call it the ultimate in green corporate branding. The Xstrata money is paying for the creation of a second wombat colony some 435 miles (700 kilometers) to the south, where some wombats were relocated to seed a new population as an insurance policy against a catastrophic fire or other calamity at Epping. [Source: Todd Woody, Time magazine, March 12, 2009]

To keep the wombat from going the way of the dodo, environmental officials gathered at Epping in late 2007 to brainstorm a radical shift in strategy: they would abandon business as usual by embracing Big Business. The wombat program had operated on a shoestring budget for years, and millions were needed to establish the second colony. "To do this properly, we need the big bucks," said Queensland wildlife-conservation chief Rebecca Williams, sitting at a table outside the ramshackle trailer that serves as the camp's kitchen and makeshift lab. "So think differently."

Also at the table was Wes Mannion, head of Australia Zoo, the for-profit founded by the late Steve Irwin, the "Crocodile Hunter." The zoo had inked a deal with the government to help save the wombat, mainly through research support. "It's all about the marketing and money, mate," chimed in Mannion, an Irwin look-alike in his Aussie safari outfit. That view won over Alan Horsup, a conservation officer who spent the past two decades in an often lonely quest to pull the northern hairy-nose back from the edge of extinction. "I didn't like it at first," he said of corporate sponsorship. "But bloody hell, why can't we have the BHP wombat?"

That would be BHP Billiton, mate, an Xstrata rival. In fact, Geoff Clare, an executive director of Queensland's Environmental Protection Agency, had mining in mind because the industry had raked in record profits thanks to Australia's commodity boom. Some green sheen wouldn't hurt the industry one bit. So in February 2008, Queensland's top environmental officials walked into the Australian headquarters of Xstrata and made the pitch. For Xstrata Coal CEO Peter Freyberg, investing an initial $3 million in the wombat was a no-brainer. "There's obviously benefit in terms of the way people perceive Xstrata," says Freyberg.

Xstrata is not just writing a check. Freyberg says the company will play a hands-on role in the relocation project. "The wombat is massively endangered," he says. "Without our intervention, this animal would be at serious risk." In November, Freyberg made the trek to Epping, where he had a own close encounter with a northern hairy-nose late one night.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025