Home | Category: Pinnipeds (Seals, Sea Lions, Walruses)

RINGED SEALS

Ringed seals (Pusa hispida) inhabit the circumpolar pack-ice waters north to North Pole. Adults average 1.25 meters (four feet) in length. These seals can live in completely ice-covered waters, using their stout claws to dig and maintain breathing holes. They excavate snow caves on sea ice to provide insulated shelters for themselves and their pups. Young ringed seal pups cannot survive in water. They are susceptible to temperature stresses until they grow a blubber layer and shed their lanugo, the white, wooly coat they're born with. Pups are born in snow caves or tunnels Ringed seals are hunted by Inuit for fur, meat and blubber.

Ringed seals are the smallest and most common Arctic seal. They get their name from the small, light-colored circles, or rings, that are scattered throughout the darker hair on their backs. They are found in all seasonally ice-covered seas of the Northern Hemisphere and in certain freshwater lakes. Throughout their range, ringed seals have an affinity for ice-covered waters and are well-adapted to occupying heavily ice-covered areas throughout the fall, winter, and spring. Ringed seals remain in contact with the ice most of the year. The ice and snow caves provide some protection from predators, though polar bears spend much of their time on sea ice hunting ringed seals, which are their primary prey. Snow caves also protect ringed seal pups from extreme cold. Loss of sea ice and snow cover on the ice poses the main threat to this species. [Source: NOAA]

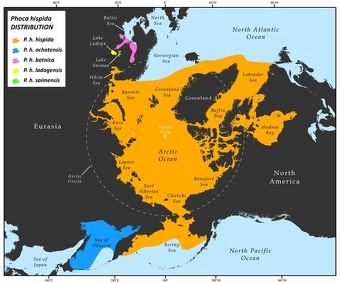

There are five currently recognized subspecies of the ringed seal. 1) Arctic ringed seals live in the Arctic Basin and adjacent seas, including the Bering and Labrador Seas; 2) Okhotsk ringed seals occur in the Sea of Okhotsk; 3_ Baltic ringed seals live in the Baltic Sea; 4) Ladoga ringed seals are found in Lake Ladoga, Russia; and 5) Saimaa ringed seals reside in Lake Saimaa, Finland. There has been some debate as to whether ringed seals should be placed in the genus Pusa or the genus Phoca in recent decades. Most taxonomists use the name Pusa but it is not universally accepted.

There are estimated to be over 2,100,000 ringed seals. The subspecies of the ringed seal are listed here with their scientific names and population estimates: 1) Arctic ribbon seals (P. h. hispida), 2,000,000; 2) Baltic seals (P. h. botnica), 11,500; 3) Ladoga seals (P. h. ladogensis), 3,000–4,500; 4) Okhosk ringed seal (P. h. ochotensis), 60,000; and 5) Saimaa ringed seal (P. h. saimensis), endangered, 135–190.

Related Articles:

CATEGORY: SEALS: ioa.factsanddetails.com;

SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES, WHISKERS, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com;

SEALS: HISTORY, BEHAVIOR, DIVING, FEEDING, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEA LIONS AND FUR SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEALS AS PREY FOR ORCAS, GREAT WHITES AND POLAR BEARS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SEALS AND HUMANS: CLOTHES, HUNTS AND THE MILITARY ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SEAL AND SEA LION ATTACKS ON HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

NORTHERN SEALS: ARCTIC, SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

HARBOR SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BEARDED SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LEOPARD SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND PENGUINS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

STELLER SEA LIONS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION: ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

CALIFORNIA SEA LIONS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

FUR SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ELEPHANT SEALS, THEIR BEHAVIOR AND AMAZING DIVING ABILITY ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

NORTHERN ELEPHANT SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SOUTHERN ELEPHANT SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALRUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Ringed Seal Habitat and Where They Are Found

Ringed seals are circumpolar and range throughout the Arctic Basin and southward into adjacent seas, including the Bering and Labrador Seas, ranging from 35°N, to the North Pole. They are also found in the Sea of Okhotsk and Sea of Japan in the western North Pacific and the Baltic Sea in the North Atlantic. Landlocked populations inhabit Lakes Ladoga (Russia) and Saimaa (Finland). [Source: NOAA]

Ringed seals are circumpolar and range throughout the Arctic Basin and southward into adjacent seas, including the Bering and Labrador Seas, ranging from 35°N, to the North Pole. They are also found in the Sea of Okhotsk and Sea of Japan in the western North Pacific and the Baltic Sea in the North Atlantic. Landlocked populations inhabit Lakes Ladoga (Russia) and Saimaa (Finland). [Source: NOAA]

During winter and spring in the United States, ringed seals are found throughout the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas; they occur in the Bering Sea as far south as Bristol Bay in years of extensive ice coverage. Most ringed seals that winter in the Bering and Chukchi Seas are thought to migrate northward in spring with the receding ice edge and spend summer in the pack ice of the northern Chukchi and Beaufort Seas.

Ringed seals are are native to the Arctic Ocean. Distinct populations occur in the Baltic Sea, Lake Ladoga of the Russian Federation, Lake Saimaa in Finland and the Sea of Okhotsk near Japan. In the Atlantic Ocean, ringed seals may be found as far south as New Jersey and Portugal. They have also been found in the Pacific, south to Zhejiang in China and near California. [Source: Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Through much of their range, ringed seals do not come ashore. Instead they inhabit Arctic waters and are commonly found with ice floes and pack ice, which is used for resting, pupping and molting. They prefer large floes (more than 48 meters in diameter) and are commonly found in the interior ice pack where the sea ice coverage is greater than 90 percent. Ringed seals tend to inhabit areas near the breathing holes they create or ice cracks, in order to escape predation. In more southerly regions and in lakes Ladoga and Saimaa, ringed seals rest on rocks, island shores and offshore reefs when ice is absent. They are distributed in waters of nearly any depth during non-breeding or molting seasons. Ringed seals are believed to move south with sea ice advancement and north when ice declines in the spring. Their distribution is also strongly correlated with food availability.

Ringed Seal Characteristics

Ringed seals are the smallest pinnipeds (seals and sea lions). They range in weight from 32 to 124 kilograms (70.5 to 273.1 pounds) and are 1.1 to 1.75 meters (3.6 to 5.7 feet) in length. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. [Source: Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Ringed seals have small heads, short cat-like snouts and and plump bodies. Their coat is dark with light-colored rings on their back and sides, and a light-colored belly. Their small foreflippers have thick, strong claws that are used to maintain breathing holes through two meters or more of ice. Pups are born with a lanugo (woolly coat) of white insulating hairs, which they shed within three weeks. They weigh 4.5 kilograms at birth and double their weight within two months. The succeeding coat is slightly longer and finer than that of adults. This coat is dark gray dorsally with a silver belly and a few scattered dark spots on the ventral side. There are few, if any, rings dorsally. This stage is known as “silver jars”.

The five ringed seals subspecies — 1) Arctic (Pusa hispida hispida), 2) Baltic (P. h. botnica), 3) Lagoda (P. h. ladogensis), 4) Okhotsk (P. h. ochotensis) and 5) Saimaa (P. h. saimensis) — vary in size. Baltic ringed seals are the largest subspecies, ranging between 1.5 to 1.75 meters in length and weighing between 110 to 124 kilograms. The Arctic and Okhotsk ringed seals are between 1.1 to 1.5 meters in length and weigh between 50 to 70 kilograms. Females are slightly smaller than the males. Saimaa ringed seals measure up to 1.5 meters and weigh between 45 to 100 kilograms. Most have a dark gray-black coat, but there is substantial variety.

Ladoga ringed seals are the smallest, weighing between 32 to 56 kilograms. Their longer whiskers and darker coats make them unique compared to the other subspecies. In addition, their rings are lighter colored with light vein-like patterns. Some Ladoga individuals have a black belt around their body with indistinct rings and brown spots in warmer weather.

Ladoga Ringed Seals — Freshwater Seals

Ladoga ringed seal is a freshwater subspecies of the ringed seal (Pusa hispida) which are found entirely in freshwater Lake Ladoga. The subspecies evolved during the last ice age, about 11,000 years ago. As the glaciers retreated and water levels changed, the Baltic ringed seal (including Ladoga seals) was trapped in freshwater lakes and separated from the Arctic ringed seal. It is related to the even smaller population of Saimaa ringed seals in Lake Saimaa, a lake that flows into Ladoga through the Vuoksi River.

The adult Ladoga seal grows to about 150 centimeters in length and weighs approximately 60–70 kilograms. Females are pregnant for about 11 months. In February-March, they give birth to usually one pup in a burrow dug in the snow on ice hummocks. There are about 2,000–3,000 of them, down from approximately 20,000 at the beginning of the 20th century. Hunting took its toll on the these animals and was banned in 1980. Today they are threatened by fishing nets and other fishing gear and disturbances from motor boats and snowmobiles where the seals breed and rest.

The Ladoga seal is the smallest of all subspecies of ringed seals. It and the Baltic and Saimaa subspecies are products of the postglacial period after the last ice age. The Ladoga seal, Saimaa seal, Lake Baikal seal and manatees are the only marine mammal whose entire life cycle takes place in freshwater. The best time to see Lake Ladoga seals is during ice-free times when they rest on land, particularly in the Valaam archipelag on the islands of Naked, Holy, Black, Big Bayonne, Pine, East Pine, Lembos, Extreme, Cross and Fox. In calm weather 600 - 650 seals can be found resting at different spots on the shores. Tourists can reach the islands by boat; and see the seals from boat tours.

Ringed Seal Food and Eating Behavior

Ringed seals are carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and piscivores (eat fish). They eat a wide variety of mostly small prey. They rarely prey on more than 10 to 15 species in any specific geographic location, and not more than two to four of these species are considered important prey. Despite regional and seasonal variations in the diet of ringed seals, fishes of the cod family tend to dominate the diet in many areas from late autumn through spring. Crustaceans appear to become more important in many areas during the open-water season and often dominate the diet of young seals. While foraging, ringed seals dive to depths of up to 50 meters (164 feet) or more. [Source: NOAA]

In addition to fishes, ringed seals eat cephalopods (squid and octopus), amphipods (a kind of crustacean),euphausiids (krill and similar animals), mysids (opossum shrimps) and other kinds of shrimp. Important prey species typically form large groups. Seals from northwestern Norway feed on polar cod in the spring, and fishes from the Stichaeidae and Cottidae families after that. In waters off Alaska, other members of the cod family, including Arctic cod and saffron cod, are important food sources during the summer. In northeastern Greenland, the autumn diet of ringed seals is comprised of the small crustacean, Themisto libellula, while their spring diet is composed of polar cod and a few invertebrates. [Source: Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The coastal diets of ribbon seals have a greater diversity of fish during autumn and spring than open water seals, which mainly consume crustaceans. Ringed seals seem to prefer fish over crustaceans, even when crustaceans are in great abundance. Young seals feed on a higher portion of crustaceans than adults. Ringed seals reduce their feeding during the spring molt. In the fall, prey availability determines breathing hole locations. At this time seals put on fat for the winter. |=|

Ringed Seal Behavior

Ringed seals can live in areas that are completely covered with ice. They use their sharp claws to make and maintain their own breathing holes through the ice, which may be six feet or more in thickness. In winter through early spring, they also carve out lairs in snowdrifts over their breathing holes. As the temperatures warm and the snow covering their lairs melts during spring, ringed seals transition from lair use to basking on the surface of the ice near breathing holes, lairs, or cracks in the ice as they undergo their annual molt. Ringed seals do not live in large groups and are usually found alone, but they may occur in large groups during the molting season, gathered around cracks or breathing holes in the ice. [Source: NOAA]

The home range size of ringed seals varies seasonally and is based on gender. Adult males tend to keep a home range size of one to 13.9 square kilometers, whereas adult females maintain a one to 27.9 square kilometer home range. During the winter months, when their movement is restricted due to ice, they may travel no more than one to two square kilometers. In the summer, they may travel up to 1,800 square kilometers away from their winter home ranges. [Source: Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Seals in the Baltic Sea and the freshwater bodies Lake Saimaa and Lake Ladoga display similar seasonal patterns to other ringed seals, however, they are forced to haul out on islands and shores during the summer when ice is absent. Ladoga ringed seals have a unique social structure by forming large herds during the open water period with mass haul outs. Their average territory size is 1- 27.9 square kilometers.

Ringed seals communicate with vision, touch and sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. All pinnipeds have limited auditory systems because of their water-and-open-air lifestyle. They cannot produce or receive highly developed, acute, aquatic, high frequency sounds. According to Animal Diversity Web: Instead, they have advanced visual, tactile and passive listening skills, which aids in foraging, navigating and evading predators. Underwater, pinnipeds produce a wide variety of signals including whines, grunts, roars, chirps and pulsed sounds related to social behavior and reproduction. Ringed seals use sound cues to find holes in the ice, which helps them develop conceptual maps of the area under the ice.

Ringed Seal Predators

Ringed seals are primarily predated upon by polar bears, Arctic foxes, some birds and humans.

They seals are an important food source in particular for polar bears. During the pupping season, Arctic foxes and glaucous gulls take ringed seal pups born outside lairs. Orcas (killer whales), Greenland sharks and occasionally Atlantic walruses prey upon them in the water. Inuit hunters often target structures that are near ice ridges. The ridge height and snow depth influences human success. The presence of “tiggak”, or the rutting male odor of ringed seals, lowers the chance of predator attacks

Ringed seal pups are quite vulnerable to predation. Foxes generally prey only young not adults. One study found that Arctic foxes had dug into 46 percent of the studied seal birth lairs in Svalbard, Norway and successfully killed 18 percent of the pups. Pups born in exposed areas outside of lairs are especially vulnerable to avian predators, primarily glaucous gulls. The difficulty making ice lairs may be a primary limiting factor ringed seal southern breeding ranges. [Source: Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

As means of protection and defense, ringed seal pups keep their white-coat, which serves as camouflage on snow and ice, for a relatively long time and develop diving skills at an extraordinarily early age. An estimated 50.3 percent of their time is spent in the water and they use multiple breathing holes to avoid predation. Adults establish breathing holes in landfast ice as ice forms in autumn, which is then maintained by the seals heavy claws. With accumulating snow, ringed seals excavate their lairs above breathing holes. They are never far from a breathing hole while on ice and use them as a primary escape method from predators in addition to maintaining multiple lairs.

Ringed Seals and Polar Bears

Ringed seals are the primary prey of many polar bears, with seal pups being a particular favorite. These pups are born in the spring in little caves hollowed out of snow drifts by their mothers above their breathing holes in the sea ice. The seals are well hidden but the bears can locate the pups with their amazing sense of smell. The polar bears kill the pups with a bite to the head. The 25-kilogram pups are almost half fat.

Polar bear hunt seals mostly from ice flows. They wait for coastal waters to freeze and then live a solitary life of seal hunting. The bears often ignore the meat and gorge themselves on the fat, which they need for energy. Polar bears hunt seals mainly using two methods: by stalking seals from land or underneath ice after they have emerged at breathing holes; or by waiting patiently near the seal's breathing hole and biting its head as it surfaces for air.

Polar bears are so strong they can reach inside a hole in the ice, kill the seal with a single, crushing bite and then pull it out of the water using its strong neck and shoulder muscles. Sometimes polar bears break through the ice with their paws to catch seals and fish.

Field studies in Canada have shown that, on average, a polar bear in the High Arctic kills 43 ringed seals a year. An estimated 47 percent of those killed are pups caught in April to May, while 30 percent are newly weaned pups killed from June to July. Arctic foxes commonly scavenge the remains left by polar bears. Approximately 26.1 percent of pup predation occurs in their subnivean birth lairs. Polar bear predation decreases with increasing snow depth and the thickness of lair roof coverings. [Source: Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

See Separate Article POLAR BEARS factsanddetails.com ;

Ringed Seal Mating and Reproduction

Ringed seals are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and employ delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months). Ringed seals breed once a year. Their breeding season generally occurs from April to May. The average gestation period is 11 months, including the delayed implantation. The the average number of offspring is one. Most females breed within a month of giving birth, but embryo implantation is delayed until mid-July or early-August means that their pregnancy lasts about 11 months. Traditionally, ovulation first occurs at five to six years of age, but since 1999, the average age of sexual maturity among female ringed seals has decreased to an average of 3.2 years. Females usually produce pups when they are between six and eight years of age. Males typically do not participate in breeding until eight to 10 years of age. |Source: NOAA Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Sexual maturity in ringed seals varies with population status. It can be as early as three years for both sexes and as late as seven years for males and nine years for females. The timing for ringed seals breeding can vary regionally. Mating takes place while mature females are still nursing their pups on the ice and is thought to occur under the ice near birth lairs.Pinniped species tend to engage in polygyny in part because of the high concentration of estrus females. Ringed seals get around this to some extent by under-ice breeding.

During the breeding season, breeding seals occupy pack ice instead of their preferred shorefast sea ice (ice attached to the coastline). This may to protect pups from predators , which is likely due to the distance from the shore rather than the type of ice. In addition, breeding sites may be selected based on prey availability. Some ringed seals populations have restricted movements during the breeding season, as they are ice-bound. Baltic, Saimaa and Arctic ringed seals tend to display strong fidelity to particular sites, but some studies suggest that Arctic ringed seals range over a wide area.

Males maintain large, under-ice territories that encircle several female territories. The above and below territories of females are larger than those of males with more overlap. Males often position themselves near the primary breathing holes of post-parturient females until they are receptive. During this time, males may share breathing holes with females. Rutting males exhibit territorial, behavior and emit a strong scent from their facial glands that smells like gasoline. They often have fresh wounds to their hindflippers from male-to-male conflicts at the beginning of the breeding season. Increased vocalizations have been documented at this time.

Ringed Seal Offspring and Parenting

Ringed seal young are precocial. This means they are relatively well-developed when born. Parental care is provided by females. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. The weaning age ranges from five to seven weeks. Females normally nurse their pups on the ice in snow-covered lairs in late winter through early spring. Females reach sexual maturity at 3.2 to six years; males do so at eight to 10 years. [Source:Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

In all subspecies except the Okhotsk, females give birth to a single pup hidden from view within a snow-covered birth lair. Ringed seals are unique in their use of these birth lairs. Although Okhotsk ringed seals have reportedly used them, this subspecies apparently depends primarily on the protective sheltering of ice hummocks (rounded hills of ice). Pups learn how to dive shortly after birth. They are nursed for as long as two months in stable ice that is fastened to the coastline and for as little as three to six weeks in moving ice. Pups are normally weaned before the break-up of spring ice. [Source: NOAA]

Most ringed seals give birth in subnivean lairs (burrows underneath the snow layer) . Rebekah Spicer wrote in Animal Diversity Web” These lairs are essentially snow-covered caves on ice floes that accumulate upwind and downwind of ice ridges or in cavities between ice blocks in pressure ridges. Adult females build lairs above breathing holes; this is a unique birthing habitat, which only ringed seals use. These lairs offer thermal protection to the pups against wind chill and cold weather and minimal protection against predators. During this subnivean period, mothers spend nearly 50 percent of their time in the water. Mothers may take pups in the water, but they need to return to the lair after a short duration because of the cold environment. Swimming is taught by the mother within the first week of life. Pups are weaned after two months, usually concurring with ice breakup, during which they gain weight and blubber. Afterward, the pups must learn to feed themselves, often loosing the blubber they had gained. |=|

Pups are born in late winter or early spring. The single pup born annually to a hominin on average weighs 10 pounds at birth. They are nursed for roughly two months, during this time they double their weight. Their lactation period, is the longest lactation period among family Phocidae. During this time, mothers move young pups between her lairs (commonly four to six lairs per female). When the pups are older, this allows them to move independently between shelters if attacked.|=|

Ringed Seals, Humans and Conservation

Ringed seals as a whole are not endangered. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List due to their broad distribution and sizable populations They have no special status according to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The Arctic ringed seal is the most abundant subspecies with over 2 million individuals, including 300,000 in U.S. waters. There are only a few thousand of the Ladoga and Saimaa subspecies, the latter of which is considered endangered. Threats to ribbon seals include climate change, entanglement in fishing gear (particularly with the Ladoga and Saimaa subspecies), increasing arctic shipping activity, offshore oil and gas exploration and development.

There has been significant commercial harvest of ringed seals in the Sea of Okhotsk off eastern Russia and predator-control harvests in the Baltic Sea and Lake Ladoga in the past, but these are is currently restricted. The Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 protects ringed seals from harvest with the exclusion of subsistence harvest by Alaskan native hunters. Quotas and licensing for harvest has been in place throughout the Russian Federation for decades. Alaskan natives use ringed seals for food and oil. Ringed seals' skin are used for clothing, equipment and crafts. The oil is important in different foods and is traded inland. They often use this oil on bearded seals' skins and sinews while sewing boat covers to make the stitches waterproof. Harvests of Arctic ribbon seals may be significant in many northern coastal communities, but has been deemed sustainable. [Source: Rebekah Spicer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Many aspects of the ringed seal’s life cycle depend directly on the species’ sea ice habitat. As such, the ongoing and anticipated reductions in the extent and timing of ice cover, especially on-ice snow cover, stemming from climate change poses a significant threat to this species. If a large amount of ice habitat is lost, ringed seals will be negatively impacted during pupping and rearing of young. Insufficient ice results in poor pup conditions and higher mortality rates. [Source: NOAA]

Baltic ringed seals are increasing at their primary breeding sites, but recent population-wide declines have occurred, along with current declines in some of their range. Ladoga and Saimaa ringed seals are probably the most threatened subspecies. Ladoga ringed seal have declined substantially in recent decades, primarily due to by-catch mortality in fishing gears and climate change. Saimaa ringed seals have an extremely small population that faces by-catch mortality. In recent years, they have suffered virtually complete reproductive failure, due to poor ice conditions within their range. The U.S. Federal list considers this subspecies Endangered. On the other hand, Okhotsk ringed seals have not been censused since the late 1960s, so population numbers and trends are unknown.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025