Home | Category: Pinnipeds (Seals, Sea Lions, Walruses)

ARCTIC AND NORTHERN SEAL SPECIES

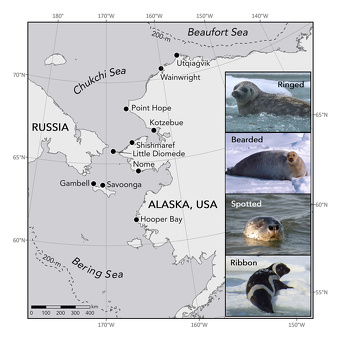

Arctic Seal Species:

Ringed seal (Pusa hispida), 1,500,000: Subspecies: P. h. hispida, 1,450,000; Baltic seal (P. h. botnica), 11,500; Ladoga seal (P. h. ladogensis), 3,000–4,500; Okhosk ringed seal (P. h. ochotensis), 60,000; Saimaa ringed seal (P. h. saimensis), endangered, 135–190.

Ribbon seal (Histriophoca fasciata), 183,000

Harp seal (Pagophilus groenlandicus), 4,500,000

Northern Seal Species:

Harbor seal (Phoca vitulina): Subspecies: East Atlantic harbor seal (P. v. vitulina), 62,500;

West Atlantic harbor seal (P. v. concolor) 60,000; Freshwater seal (P. v. mellonae), endangered, 50; North Pacific harbor seal (P. v. richardii), 190,000; Kuril Island seal (P. v. stejnegeri), 315,000

Spotted seal (Phoca largha), 320,000, found in Bering Sea and surrounding areas

Gray seal (Halichoerus grypus), 316,000: Subspecies: H. g. grypus, 250,000; H. g. macrorhynchus, 66,000;

Bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus), 200,000.

Many Arctic and northern seal species are affected by climate change as they rely on the availability of suitable sea ice — as a haul-out platform for giving birth, nursing pups, and molting — and sea ice formation in the Arctic has been significantly altered by climate change. Some places that had lots of ice before don’t have as much now and ice often appears later and melts earlier than it did in the past. Many seals are sensitive to changes in the environment that affect timing and extent of sea ice formation and breakup. A 2013 study found that it is likely that ongoing and projected changes in sea ice (and possible changes to seal prey base related to changes in ocean conditions) will result in a gradual decline in seal abundance. [Source: NOAA]

The continuing decline in summer sea ice in recent years has renewed interest in using the Arctic Ocean as a potential waterway for coastal, regional, and trans-Arctic marine operations, which pose varying levels of threat to ribbon seals depending on the type and intensity of the shipping activity and its degree of spatial and temporal overlap with the seals. Offshore oil and gas exploration and development could also impact ribbon seals. The most significant risk that these activities pose is accidentally or illegally discharging oil or other toxic substances, which would have immediate and potentially long-term effects. Ribbon seals could also be directly affected by noise and physical disturbance of habitat associated with such activities.

Related Articles:

HARBOR SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BEARDED SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

RINGED SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Ribbon Seals

Ribbon seals (Histriophoca fasciata) are among the most striking and easily recognizable seals in the world. The species gets its name from the distinctive adult coat pattern of light-colored bands or “ribbons” on a dark background. The rates of survival and reproduction are not well known, but the normal lifespan of a ribbon seal is probably 20 years, with a maximum of perhaps 30 years. There are thought to be around 250,000 of them in the Bering and Okhotsk Seas. [Source: NOAA]

Ribbon seals inhabit the North Pacific Ocean and adjacent southern parts of the Arctic Ocean, where they occur most commonly in the Sea of Okhotsk and Bering Sea. In U.S. waters off the coast of Alaska, they are found in the Bering Sea and in the Chukchi and western Beaufort Seas. Ribbon seal breeding occurs in both the Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk. Individual ribbon seals are occasionally sighted along the coasts of Asia and North America, which are not considered part of their normal range, or in unusual habitats within their range. For example, a young adult ribbon seal was observed on several occasions hauled out on docks in the inland waters of Washington state.

Although ribbon seals are strongly associated with sea ice during the whelping (or birthing), breeding, and molting periods, they do not remain on sea ice after they finish molting. During summer, ice melts completely in the Sea of Okhotsk, and by the time the Bering Sea ice recedes north through the Bering Strait, there are usually only a small number of ribbon seals hauled out on the ice. Significant numbers of ribbon seals are only seen again when the sea ice reforms in winter.

Ribbon seals are currently listed as as species of Least Concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The most recent assessment places gives them that ranking based on a lack of evidence suggesting that they could be threatened. It is estimated that there are at least 200,000 to 300,000 of them. Threats include climate change, increased shipping activity, oil and gas exploration and development. Ribbon seals, like all marine mammals, are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. They are particularly adept on ice. As such, they are sensitive to changes in the environment that affect the timing and extent of sea ice formation and breakup such as those caused by climate change. Because of uncertainties regarding the effects of climate change, related changes in sea ice, and potential Russian harvests, ribbon seals are included in NOAA Fisheries’ Species of Concern list. The 2013 status review of the ribbon seals under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Endangered Species Act concluded that it is likely that ongoing and projected changes in sea ice (and possible changes to their prey base related to changes in ocean conditions) will result in a gradual decline in seal abundance.

Related Articles:

CATEGORY: SEALS: ioa.factsanddetails.com;

SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES, WHISKERS, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com;

SEALS: HISTORY, BEHAVIOR, DIVING, FEEDING, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEA LIONS AND FUR SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEALS AS PREY FOR ORCAS, GREAT WHITES AND POLAR BEARS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SEALS AND HUMANS: CLOTHES, HUNTS AND THE MILITARY ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SEAL AND SEA LION ATTACKS ON HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

LEOPARD SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND PENGUINS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

STELLER SEA LIONS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION: ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

CALIFORNIA SEA LIONS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

FUR SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ELEPHANT SEALS, THEIR BEHAVIOR AND AMAZING DIVING ABILITY ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

NORTHERN ELEPHANT SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SOUTHERN ELEPHANT SEALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALRUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Ribbon Seal Characteristics, Diet and Behavior

Ribbon seals are medium-sized when compared with the other three species of ice-associated seals in the North Pacific, being larger than ringed seals, smaller than bearded seals, and similar in size to spotted seals. At birth, ribbon seal pups are approximately 85 centimeters (34 inches) long and weigh almost 110 kilograms (about 21 pounds). Adults are about 1.5 to 1.8 meters (five to six feet) long and weigh about 90 to 150 kilograms (200 to 330 pounds_. [Source: NOAA]

Ribbon seals gets their name from the distinctive pattern exhibited by mature individuals, which consists of light-colored ribbons that encircle the neck, each foreflipper, and hips. Adult males are the most striking, having a dark brown to black coat with white ribbons, while adult females range from silvery-gray to dark brown with paler ribbons. Juvenile ribbon seals typically have indistinct ribbons that gradually develop over three years with each successive annual molt. Ribbon seal pups are born with a thick, woolly white coat (lanugo) that is molted after three to five weeks.

Ribbon seals are considered relatively solitary, spending most of their time in the open ocean and forming loose aggregations in pack ice during spring to give birth, nurse pups, and molt. Unlike most other northern seals, they are relatively unwary of their surroundings while hauled out, which suggests they have not been exposed to the same level of predation (e.g, from polar bears and foxes). Ribbon seals move across the ice in a way that is distinct from the caterpillar-like movement of other ice seals. They alternate foreflipper strokes to pull themselves forward while moving their head and hips in a side-to-side motion. Ribbon seals are known to eat a variety of fishes, cephalopods, and crustaceans; however, information about their feeding habits is limited and mostly restricted to the spring when they typically feed less.

Ribbon seal mothers give birth to a single pup far offshore in seasonal pack ice over a period of about five to six weeks during April to early May. Most pups are weaned by mid-May, which occurs when the mother abandons the pup. The mother typically breeds again shortly after weaning. Ribbon seals are born white and attain their distinctive black and white ribbon patterns after several molts. Ribbon seals become sexually mature at one to five years of age, most likely depending on environmental conditions. [Source: NOAA]

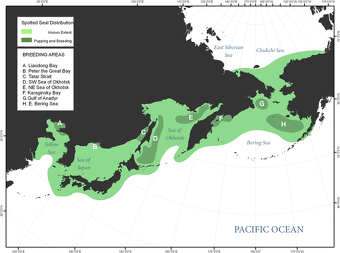

Spotted Seals

Spotted seals (Phoca largha) are found from northern Alaska to Korea. Also known as largha seals, they are similar to harbor seals but are smaller, reaching lengths of 1.7 meters (5.5 feet). Adults weigh 63 to 113 kilograms (140 to 250 pounds) and average 1.4 to 1.7 meters (4.5 to 5.5 feet in length. Their lifespan is 30 to 35 years. There are thought to be about 400,000 spotted seals in the Bering and Okhotsk Seas.

Spotted seals gets their name from their coat pattern, which is usually a light-colored background with dark spots. They are widely distributed on the continental shelf of the Beaufort, Chukchi, southeastern East Siberian, Bering, and Okhotsk Seas; south through the Sea of Japan; and into the northern Yellow Sea. From late fall through spring, spotted seal habitat use is primarily associated with seasonal sea ice. Most spotted seals spend the rest of the year making periodic foraging trips from haulout sites onshore or on sea ice. [Source: NOAA]

In U.S. waters, spotted seals migrate south from the Chukchi Sea through the Bering Strait from October to November ahead of advancing sea ice. They spend the winter in the Bering Sea in the annual pack ice over the continental shelf. During spring, they migrate to coastal habitats after the sea ice retreats. Spotted seals rely on sea ice during reproduction and to some extent during molting. As such, they are sensitive to changes in the environment that affect the annual timing and extent of sea ice formation and breakup.

Spotted seals are identified as a species of Least Concern' on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. There is estimated to be more than 500,000 of them. Threats include climate change, increasing shipping activity, and offshore oil and gas exploration and development.

Spotted seals are primarily associated with sea ice during reproduction and molting. As such, they are sensitive to changes in the environment that affect the timing and extent of sea ice formation and breakup. In particular, loss of sea ice habitat poses a significant threat to the Southern distinct population segment of spotted seals, which breeds in the Yellow Sea and Peter the Great Bay in the Sea of Japan.

Spotted Seal Characteristics, Diet and Behavior

Spotted seals have a round head, narrow snout, and small body, as well as narrow, short flippers. Adult spotted seals are silvery-gray to light gray with dark spots scattered densely on their body. Pups are born with a white coat that is usually shed at the time of weaning and replaced with a coat that is rather similar to adults. Males and females are generally similar in appearance. Spotted seals are closely related and often confused with harbor seals in areas where you can find both, such as in Bristol Bay, Alaska. [Source: NOAA]

Spotted seals are unusual among true seals in that they annually form "family" groups consisting of a female, a male, and a pup during breeding season. Spotted seals prefer Arctic or sub-Arctic waters and are often found within the outer margins of shifting ice floes. They rarely inhabit areas of dense pack ice. During breeding season, spotted seals primarily haul out on ice floes, whereas during the summer months they can be found in the open ocean or hauled out on shore.

Spotted seals consume a broad variety of mostly fishes and some crustaceans and cephalopods. While regional differences in the diet of spotted seals are noted among studies, some prey items are important across almost the entire range of the species. Pacific herring and crustaceans are major prey in all locations except the central Bering Sea, and walleye pollock is important in all regions except the Chukchi Sea. Overall, younger animals predominantly consume crustaceans, and older seals mainly eat fish. Spotted seals are not deep divers and feed almost exclusively over the continental shelf in waters less than 650 feet deep.

Spotted Seal Reproduction

Nearly all spotted seals reach sexual maturity by the time they are five years of age. Spotted seal pups are born anytime from January through April, depending on their location. The pupping and nursing season occurs earliest (January through early March) in the Yellow Sea and latest (late March through May) in the Sea of Okhotsk and Bering Sea, with a peak of pup births in the Bering Sea in early to mid-April. Females mate shortly after their pups are weaned. Males are thought to be annually monogamous, and spotted seals form "family" groups consisting of a female, male, and a pup during breeding season. Gestation lasts for just over 10 months. Their maximum lifespan is 30 to 35 years. [Source: NOAA]

Larga seal pups are covered with cream-colored fur when they are born. The fur serves as camouflage the snow, protecting them from potential predators. Their adult spots begin developing about a month after birth, around the same time they stop being breast fed and enter a period of post-weaning fasting when their weight drops from around 40 kilograms to around 30 kilograms. During that time they get their nutrition from fat stored in their bodies.

Pups are white and weigh 15 to 26 pounds at birth. They are nursed for three to six weeks, during which time they more than triple in weight. Pups born on the sea ice rarely enter the water until they are weaned and molted. During the first few weeks after weaning, pups remain at least partially dependent on ice while they become proficient at diving and foraging for themselves.

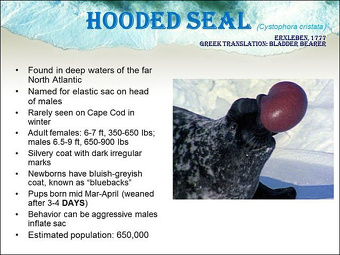

Hooded Seals

Hooded seal (Cystophora cristata) can dive very deep and hunt fish in deep waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic. Males have highly elastic black bladders on their nose and on top of their head. Both are interconnected and used in breeding displays. Males also possess a red nasal bladder, the source of their nickname bladdernose. There are around 340,000 of them. Their lifespan is 25 to 35 years.

Hooded seals live in the cold waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Adult males are known for the stretchy cavity, or hood, in their nose, which they can inflate so that it looks like a bright red balloon. They have another inflatable nasal cavity in the form of a black bladder on their head. Hooded seals are also known as bladder-nosed seals due to this unique ability. [Source: NOAA]

Hooded seals inflate their nasal bladders like elephant seals. They can close both nostrils and exhale, inflating black skin bladder, or they can close one nostril and exhale, blowing out the blood red sack. On a hooded seal male, BBC television naturalist David Attenborough wrote: “He lies lazily besides a female, he lazily blows air from one nostril to the other. If another male approaches, however, he inflates both at the same time so they come together and form a large black hood twice the size of a football. As the intruder gets closer, the resident shuts one nostril and blows down the other, inflating a nasal membrane into a gigantic scarlet balloon, he then shakes it violently from side to side so that it makes a pinging noise. This usually is enough to dissuade any intruder from persisting.”

Hooded Seal Characteristics and Behavior

Male hooded seals are about 2.6 meters (8.5 feet) long and weigh about 192 to 352 kilograms (423 to 776 pounds), while females are about two meters (6.5 feet) long and weigh about 145 to 300 kilograms (320 to 660 pounds). Both male and female adults have silver-gray fur with darker patches of different sizes and shapes across their bodies. Hooded seal pups have blue-gray fur on their backs and whitish bellies. This beautiful pelt earned them the nickname “blue-backs” and once made them a target for hunting. Pups shed their blue-gray coat when they are 14 months old. [Source: NOAA]

The stretchy cavity, or hood, on the hooded seal nose has two sections, or lobes. Adult males can inflate and extend this hood so that it stretches across the length of their face. Sexually mature males have a unique partition in their nose that, when inflated, looks like a pinkish-red balloon. They use this to attract females' attention during mating season and to show aggression toward other males.

On average, hooded seals dive 100 to 595 meters (325 to 1,950 feet below the surface for about 13 to 15 minutes in search of food, but they are also known to dive more than 3,280 feet for up to 1 hour. They eat squid, starfish, and mussels. They also eat several types of fish, including Greenland halibut, redfish, Atlantic and Arctic cod, capelin, and herring. Newly weaned pups feed on pelagic crustaceans

Hooded seals are not social. They migrate and remain alone for most of the year except during mating season. They are more aggressive and territorial than other seal species. Hooded seals begin their annual migration cycle once they reach sexual maturity. They gather at their breeding grounds for two to three weeks in the spring. After pups are born, adults stay in the breeding grounds to molt. Once they have molted, they begin their migration period for the rest of the year. Pups are weaned off their mother’s milk only three to five days after birth, the shortest weaning period of any mammal.

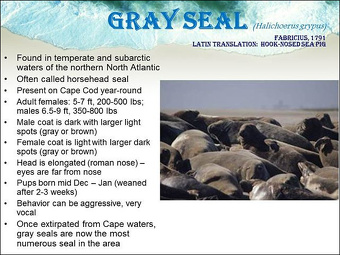

Gray Seals

Gray seals (Halichoerus grypus atlantica) are found in coastal waters throughout the North Atlantic Ocean. They are are common in Canada and northwestern Europe, with the largest concentration in the British isles. Reaching a length of 2.3 meters (7.5 feet), they are sometimes called "horseheads" because of their long snout. Adult males in particular have large, horse-like heads and large, curved noses. Gray seals gather in large groups during the mating/pupping and molting seasons. Gray seals live for 25 to 35 years. [Source: NOAA]

Gray seals are found across the North Atlantic in coastal areas from New York to the Baltic Sea. There are three stocks of gray seals worldwide: the western North Atlantic stock (eastern Canada and the northeastern United States), the eastern North Atlantic stock (Great Britain, Iceland, Norway, Denmark, the Faroe Islands, and Russia), and the Baltic Sea stock. On land, gray seals are found on rocky coasts, islands, sandbars, ice shelves, and icebergs. They share their habitat with many other species and often live in the same areas as harbor seals.

Gray seals are listed as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Gray seals, like all marine mammals, are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Even so they are harmed by human activities. Threats include entanglement in fishing nets, human-caused injuries, chemical contaminants, oil spills and energy exploration and vessel strikes.

Gray Seals Characteristics, Diet and Behavior

Gray seals are part of the "true” seal family. All true seals have short flippers, which they use to move in a “caterpillar”-like motion on land. They do not have external ear flaps. Adult female gray seals are about 2.3 meters (7.5 feet_ long and weigh about 250 kilograms (550 pounds), while adult males can reach three meters (10 feet) long and weigh about 400 kilograms (880 pounds). [Source: NOAA]

Females have silver-gray or brown fur which may or may not have scattered dark spots, while males have dark gray or brown fur which may or may not have silver-gray spots. Males also have longer noses than females. The male nose is so distinctive that the gray seal’s scientific name, Halichoerus grypus, means "hooked-nosed pig of the sea." Gray seal pups have white fur known as lanugo. This white fur helps absorb sunlight and trap heat to keep the pups warm. The lanugo is also related to their evolutionary history with other ice-breeding seals. Pups shed their lanugo when they are about three weeks old.

Gray seals gather in large groups during the mating/pupping and molting seasons. During the rest of the year, they can be found alone, in small groups or at large aggregations either on land or at sea. Only their head and neck are above the surface when they rest in open waters. Gray seals can dive to 1,560 feet for as long as one hour. On average they can eat four to six percent of their body weight in food each day, but do not eat during the mating/pupping or molting seasons. Their excellent vision and hearing makes them effective hunters. They often hunt in groups, which makes it easier for them to catch their prey. They eat fish (mostly sand eels,hake, whiting, cod, haddock, pollock, and flatfish), crustaceans, squid, octopuses, and sometimes even seabirds. Their diet varies by age class, sex, season, and geographic region.

Gray Seal Reproduction

Gray seals gather in large groups to mate. Males that breed on land can mate with many different females in a single breeding season. Gray seals breed on ice or sandy beaches in parts of Canada (Gulf of St. Lawrence, Sable Island, Nova Scotia) and on sandy or rocky beaches or islands in the U.S., and in parts of the Baltic Sea. [Source: NOAA]

Females are pregnant for about 11 months and give birth to a single pup. Females in the eastern Atlantic Ocean give birth from September to November, while females in the western Atlantic Ocean give birth from December to February. Females in the Baltic give birth in March.

At birth, newborn gray seals weigh about 16 kilograms (35 pounds). They nurse on high-fat milk for about three weeks. During this time, they gain about three pounds per day and develop a thick blubber layer. Pups shed their lanugo when they are about three weeks old. Gray seal pups are very vocal. Their cries sometimes sound like a human baby crying. This is normal behavior that helps mothers find their pups when they return to the shore from foraging. Moms don’t feed while nursing the pups, but they do use vocalizations to find pups on a crowded beach.

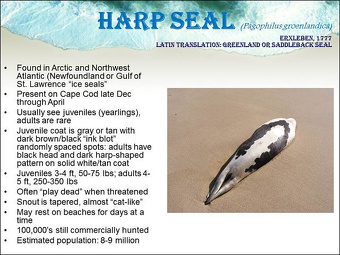

Harp Seals

Harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus) are named for the black, harp-shaped pattern on their backs. Harp seals live throughout the cold waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. Three populations in the Barents Sea, East Coast of Greenland, and Northwest Atlantic Ocean are recognized based on geographic distribution as well as morphological, genetic, and behavioral differences. Harp seals gather in large groups of up to several thousand to molt and breed. Although they live in cold water, harp seal pups are born without any protective fat. Newborns quickly develop a thick layer of blubber while nursing. [Source: NOAA]

Harp seals are part of the true seal family. All true seals have short flippers, which they use to move in a caterpillar-like motion on land. They do not have external ear flaps. Harp seals are about 1.5 to 1.9 meters (5 to 6 feet) long, weigh 118 to 136 kilograms (about 260 to 300 pounds), and have a robust body with a small, flat head. They have a narrow snout and eight pairs of teeth in both the upper and lower jaws. Their front flippers have thick, strong claws, while their back flippers have smaller, narrower claws. The maximum lifespan of a harp seal is approximately 30 years.

Adult harp seals have light gray fur with a black mask on their face and a curved black patch on their back. This black patch looks like a harp and is the source of the species’ common name. Some animals have dark spots randomly scattered over their entire body. Adults molt, or shed, their fur every spring. Harp seal pups have long, woolly, white fur known as lanugo that lasts until about 3 to 4 weeks old. This white fur helps absorb sunlight and trap heat to keep the pups warm. Pups molt several times during their development.

Harp Seal Behavior and Reproduction

Harp seals gather on pack ice in large groups during breeding and molting seasons. These groups can contain up to several thousand seals. Harp seals also feed and travel in large groups during seasonal migrations. They often travel away from the pack ice during the summer and follow the ice north to feed in the Arctic. Annual migrations can be more than 3,100 miles roundtrip Harp seals can dive up to 1,300 feet below the surface and remain underwater for about 16 minutes. They eat many(more than 130 species) different types of fish and invertebrates. Some seals have been found with more than 65 species of fish and 70 species of invertebrates in their stomachs. Their most common type of prey is smaller fish such as capelin, Arctic cod, and polar cod.

Females give birth from late February through mid-March. They will only give birth during the short period of time when pack ice is available, as the ice provides a place to nurse their pups. At birth, newborn harp seals weigh about 25 pounds and are about three feet long. They nurse on high-fat milk for about 12 days. During this time, they gain about five pounds per day and develop a thick blubber layer. Harp seals wean when they reach around 80 pounds. After weaning, adult females leave their pups on the pack ice. The pups stay on the ice without eating for about six weeks. They can lose up to half of their body weight before they enter the water and start feeding on their own. [Source: NOAA]

Harp Seal Hunt

For a while harp seals were harvested in Greenland, Newfoundland and eastern Quebec for their fur. Commercial hunters of harp seals in Canada for meat and oil had taken place since the 1600s. The Newfoundland and Quebec hunt drew some notoriety for the clubbing of baby seals. The hunt was suspended. Kennedy Warne wrote in National Geographic: Car license plates in Quebec — which includes the Magdalen Islands, or Îles de la Madeleine — bear the legend, Je me souviens, meaning "I remember." The Madelinots, as the 95 percent of islanders who are French-speaking call themselves, do not easily let go of their 250 years of history and traditions. [Source: Kennedy Warne, National Geographic, March 2004]

Madelinot fishermen remember the two decades of tribulation that began in the 1960s when antihunt campaigners, spearheaded by the International Fund for Animal Welfare and later by Greenpeace, triggered the eventual collapse of the seal trade. Portrayed as murderers and barbarians, fishermen suffered the contempt of the masses as television brought graphic scenes from the ice fields of the North Atlantic into the living rooms of Europe and North America.

Taking part in what had been known as the greatest hunt in the world — an enterprise that in the 19th century had involved more than 13,000 men and 400 sailing ships — was no longer a matter of pride but a mark of shame. Once hailed as "Vikings of the ice," the sealers were now the scum of the earth.The Madelinots' cries of Nous ne sommes pas des bouchers! — We are not butchers! — sounded hollow when accompanied by photographs of upraised clubs and bloodstained ice. PETA says the seal hunt is "nothing more than a money-making scheme orchestrated by professional fishers." Well, of course! Use PETA's letter-writing form to let Canada know about the need to protect the unique culture of the Magdalene Islands.

Today, The Canada Department of Fisheries and Oceans sets an annual total allowable catch for commercial, aboriginal, and personal use hunting. Threats to harp seals beyond hunting include, vessel strikes, entanglement in nets, habitat degradation, overfishing, chemical contaminants, oil spills and energy exploration and climate change. [Source: NOAA]

See Separate Article: SEALS AND HUMANS: CLOTHES, HUNTS AND THE MILITARY ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA, boxed species descriptions from Orleans Conservation Trust

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated June 2025