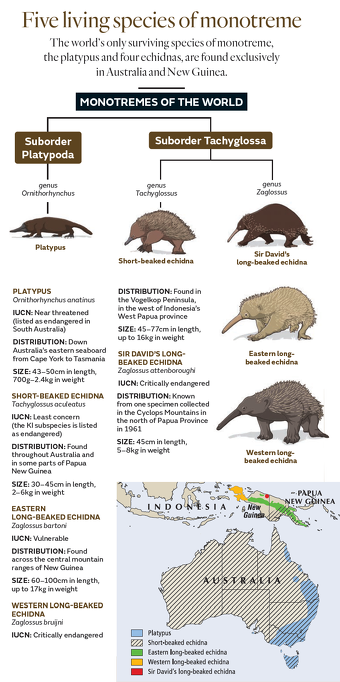

LONG-BEAKED ECHIDNAS

Long-beaked echidnas are egg-laying mammals, known as monotremes, a group that also includes the platypus and the short-beaked echidna. The family Echidnas consists of two genera; Tachyglossus and Zaglossus. The genus Tachyglossus comprises one species — short-beaked echidnas (Tachyglossus aculeatus) — while Zaglossus is composed of the long-beaked echidnas. Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) fossils of Zaglossus have been found throughout Australia and Tasmania but no extant species live there today. It has been hypothesized that the disappearance of long-nosed echidnas in Australia was due to climate changes that led to decreased presence of earthworms. [Source: Arkive; Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Long-beaked echidnas large range from 60 to 100 centimeters (two to 3.3 feet) in length and weigh five to 10 kilograms (11 to 22 pounds). Their beak length ranges from 10 centimeters to 15 centimeters (four to six inches). This length creates a downward curve in their beaks. Long-beaked echidnas have a small mouth and large nostrils at the end of the snout. The tongue is long and agile. Their limbs are powerful, with strong claws that are important in digging for food. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females and have more pronounces horny spurs on the ankles of the hind limbs.

Long-beaked echidnas are largely nocturnal and solitary and feed mainly on earthworms Their tongue has a series of backward-pointing spikes at the front, which are used to grip and reel-in worms and other prey items. During the day, individuals seek refuge in burrows, hollow logs and cavities in the ground. Long-beaked echidna usually lays one egg into its pouch, which hatches after ten days ; the infant then remains in the pouch until the spines develop. There are no teats; instead milk is lapped from 'milk patches' inside the pouch . When threatened, echidnas can erect their spines, and when on soft ground they can burrow down into the substrate so that the spine-free underside is protected. If on a hard surface they roll up into a ball, in a similar way to hedgehogs .

Two of the three Long-beaked echidnas are classified as critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. Eastern long-beaked echidnas are listed as vulnerable. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Long-beaked echidnas have been food source for some local people. Uncontrolled hunting is a threats as is loss and degradation of their habitat, much of it due to logging. The relatively large size of long-beaked echidnas and a lack of big predators in New Guinea makes them less susceptible to natural predators.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MONOTREMES: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ECHIDNAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SHORT-BEAKED ECHIDNAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLATYPUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLATYPUSES AND HUMANS: CONSERVATION, THEFTS, VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com

Long-Beaked Echidna Species

There are three long-beaked echidna species: 1) Western long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bruijni); 2) Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus attenboroughi), discovered by Western science in 1961 and described in 1998; and 3) Eastern long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bartoni), of which four distinct subspecies have been identified. Long-beaked echidnas are found only in mountainous regions of the island of New Guinea, in both Papua New Guinea in the east and West Papua on the Indonesian side in the west, at great variety of altitudes in both rainforests and alpine meadows. [Source: Arkive; Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

long-beaked echidna species ranges in New Guinea: 1) Western long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bruijni) (yellow); 2) Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus attenboroughi) (blue); 3) Eastern long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bartoni) (red)

The three species have distinct ranges; Western long-beaked echidnas are found in the far west of New Guinea; Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas are known from a single mountain peak in the Cyclops Mountains; and Eastern long-beaked echidnas are principally found in a swathe along the centre of the island, where each of the four subspecies have separate ranges.

The taxonomy of long-beaked echidnas have been debated. Until fairly recently only one species was acknowledged — Western long-beaked echidnas — and as only small morphological differences distinguish them from species from Eastern long-beaked echidnas. It is difficult to tell them apart. The species within this genus range in size from the largest living monotremes — Eastern long-beaked echidnas — at almost a meter long, to the small Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas. There is a wide variety of color and density of fur even within each species, ranging from black individuals in which the spines are barely noticeable, to sparsely haired paler echidnas In general, Western long-beaked echidnas are distinguished by the possession of three claws on the fore and hindfeet, whereas there are five on the forefeet of Eastern long-beaked echidnas and Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas. Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas are much smaller than the other species, possessing a shorter beak and shorter fur.

Western Long-Beaked Echidnas

Western long-beaked echidnas(Zaglossus bruijnii) are also known as New Guinean echidnas. Originally described as Tachyglossus bruijnii, they the type species for the genus Zaglossus and live in the far west of New Guinea in West Papua, Indonesia. Long-nosed echidnas primarily inhabitate mountain forests, although some live on highly elevated alpine meadows. They do not live along the coastal plains. [Source: Danielle Cross, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, Western long-beaked echidnas are listed as Critically Endangered, the highest threat category, just short of extinction. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. The main threats are hunting with trained dogs by local people and loss forest habitat due to farming.

Western long-beaked echidnas range in weight from five to 16.5 kilograms (11.01 to 36.34 pounds). They have a a very short tail and their head and body length ranges from 45 to 77,5 centimeters (17.7 to 30.5 inches). Their average basal metabolic rate is 6.493 watts. Most of their body is covered in course brown or black hair that often hides the spines covering the back. The downcurved snout of Western long-beaked echidnas accounts for two-thirds of the length of their head. Instead of teeth they have rows of spikes and horny teeth-like projections on their tongues. Their clawed front feet are important for digging for food. Many individuals only have claws on the middle three of the five digits. Males can be distinguished from females by the presence of a spur on the inner surface of each hind leg near the foot.

Western long-beaked echidnas are mostly solitary. Their reproductive behavior is believed to be similar to the reproductive pattern to other echidna species. The diet of Western long-beaked echidnas consists almost exclusively of earthworms. When earthworms are eaten, they are positioned to go front first into the snout. The powerful tongue of the long-nosed echidna protrudes a small distance and wraps around the front of the worm. While the worm is pulled into the mouth, the echidna's tongue holds the worm in place with its spikes. Termites and other insect larvae are also eaten, they may eat ants. It is thought that the breeding season for the long-nosed echidna is in July. A captive bruijni specimen lived for a record 30 years and eight months. |=|

Attenborough's Long-Beaked Echidna

Attenborough's long-beaked echidna (Zaglossus attenboroughi) are also known as Sir David's long-beaked echidnasor locally as Payangko. Named in honor of naturalist Sir David Attenborough, they live in the Cyclops Mountains, which are near the cities of Sentani and Jayapura in the Indonesian province of Papua in Western New Guinea. Between their initial discovery in 1961 and the first video footage taken of them in November 2023, there have been no confirmed sightings of these echidnas even by local people.

Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas live in tropical areas in rainforests and mountains at elevations of 200 to 1700 meters (656 to 5577 feet). Their range may once stretched along the North Coast Ranges. These echidnas have been important culturally to the communities surrounding the Cyclops Mountains. Sometimes disputes were resolved the two parties involved in the dispute sharing a meal of echidna. At other times, people are punished by either having to pay a fine or by having to find an echidna in the mountains.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas are listed as Critically Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. |Source: Stephanie Galarza, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas were thought to be extinct until 2007, when an expedition led by EDGE team members discovered evidence they still existed. Currently, there is a conservation effort underway where the original specimen was found. The Cyclops Mountains Strict Nature Reserve was created to protect the habitat of Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas. Currently, it is believed that hunting and loss of habitat due to farming and mining are the main reasons for the threat to their survival.

Attenborough’s Long-Beaked Echidna Characteristics, Behavior and Reproduction

Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas are the smallest echidna species, Their average weight is two to three kilograms (4.4 to 6.6 pounds). Their average length is 30 centimeters (11.81 inches). The snout of this species is approximately seven centimeters (2.8 inches) long and is somewhat straighter than other echidna species. The short snout and their size makes them appear similar to short-beaked echidnas. They have five claws on each foot and adult males have a small non-venomous spur on the inside of each ankle. Adult females lack these spurs. The fur is distinctive, short, fine, and dense, unlike other echidnas, and raw umber brown in color. There is short fur that covers the few spines on the middle back. The spines are almost white and are most dense nearest the tail. Adults have no teeth, but the tongue is covered in teeth-like spikes. Like other Zaglossus species, they have no external genitalia; making sex determination difficult.

Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas are terricolous (live on the ground), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary. It is believed that they feed on mostly worms and larvae. Researchers have identified holes in the ground made by their snouts as they poke for food. Like other echidnas, Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas are likely to use electroreception to find food. They have electroreceptors on the tips of their snouts, which they can press to the ground or other objects to detect living organisms and to perceive the environment.

All echidna lay eggs. Not much is known about the reproductive or mating behaviors of Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas because only two specimens have been found to date. It is unknown when these animals breed or whether they are promiscuous or not. Most of what is surmised about them is based on other echidna species. It is thought that Attenborough’s long-beaked echidnas females lay one egg and care for and protect their young in a pouch after their hatching and then stay in dens after that.

Eastern Long-Beaked Echidnas

Eastern long-beaked echidnas (Zaglossus bartoni) are also known as Barton's long-beaked echidnas. They mainly occur in central and eastern New Guinea at elevations between 2,000 and 3,000 meters (6,600 and 9,900 feet). These echidnas were not considered a separate species until 1998 when Flannery and Groves published their paper establishing them as distinct from Western long-beaked echidnas based on geographic location and morphology. Fossil echidnas found in Australia and New Guinea that date back to the Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) are very similar to living species. [Source: Wikipedia]

Eastern long-beaked echidnas are found east of the Paniai Lakes region of New Guinea in the Central Cordillera (the central highlands) and in the Huon Peninsula, both mountain ranges in New Guinea. Though they have a relatively wide distribution across New Guinea, they are sparsely populated throughout much of this range. [Source: Peter Flynn, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Eastern long-beaked echidnas have been observed at elevations from sea level to 4150 meters (13,615 feet). Their habitat is generally limited to the cooler, mountain summits of New Guinea but they also inhabit tropical montane forests and sub-alpine and alpine grasslands. Montane rainforests between 1,000 to 3000 meters (3,300 and 9,000 feet) are rich in wildlife and have many trees. At higher elevations, in the sub-alpine and alpine grasslands (3000 meters or higher), there is less diversity of flora and fauna. Eastern long-beaked echidnas live in burrows underground or in dense vegetation. When underground, the dens are covered with little vegetation and are usually found on slopes because it is easier the echidnas to dig into them.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Eastern long-beaked echidnas are listed as vulnerable. Before 2016 they were listed as Critically Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Population size decreased by 80 percent over a 50 year period. Eastern long-beaked echidnas lack local native animal predators. Their decline has mainly been attributed to hunting and loss of habitat the conversion of their habitat into agricultural land. The Papua New Guinea Institute of Biological Research established a long-term conservation research project, headed by Muse Opiang. The goal is to illuminate the reproduction, ecology, and natural history of this species.

There are four recognized Eastern long-beaked echidna subspecies, with each one being geographically isolated from the other:

Zaglossus bartoni bartoni, a nominate subspecies, found in the Highlands Region.

Zaglossus bartoni clunius is endemic to the Huon Peninsula of the Morobe Province. They have five digits on each foot, rather than just the forefeet. They are divided from other subspecies by the lowlands of the Markham Valley. The distinctiveness of this subspecies supports the high endemism of mammals in Huon.

Zaglossus bartoni smeenki is the smallest subspecies. They have five digits on each foot, rather than just the forefeet and are endemic to the Nanneau Mountain Range of the Oro Province.

Zaglossus bartoni diamondi is the largest subspecies, and the largest extant monotreme. They are found throughout the mountains of central New Guinea, from the Paniai Lakes in Indonesia's Central Papua Province to the Kratke Range in Papua New Guinea's Eastern Highlands Province. [Source: Wikipedia]

Eastern Long-Beaked Echidna Characteristics

Eastern long-beaked echidnas are the largest living echidnas and monotremes. They range in weight from five to 16.5 kilograms (11 to 36.3 pounds), with their average weight being 6.5 kilograms (14.32 pounds). They range in length from 30 centimeters to almost one meter (one to three feet), with their average length being 55.6 centimeters (21.89 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Females ay be slightly larger than males. Males and females have different shapes. Ornamentation is different. Males possess a spur on their ankle, which is lacking in females. However, some juvenile females possess the spur. Females have significantly longer snouts than males. [Source: Peter Flynn, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Eastern long-beaked echidnas have long, dense black to dark brown fur and white spines that cover the entire back and sides of the body. Their spines are sometimes hidden behind long fur. They have long, tubular snout with an average length of 12.3 centimeters (4.8 inches). Both males and females have a cloaca: a single orifice for the passing of feces, urine, eggs (in females) and sperm (in males). The longest recorded lifespan of an Eastern long-beaked echidna was from an animal at the London Zoo that lived 30 years.

Eastern long-beaked echidnas are heterothermic (having a body temperature that fluctuates with the surrounding environment) endotherms; they depend on movement and shivering to help generate body heat. The lowest body temperature of a captive individual was measured at 24.2̊ C (75.5̊F) . The highest body temperature was 34.2̊ C (93.6̊F). The average body temperature of captive populations was in the low 30s C (upper 80s and low 90s F). The basal metabolic rate was recorded at 24.41 kJ per hour.

The main morphological difference between western long-beaked echidnas and eastern long-beaked echidnas are the difference in claw number on the forefoot. Eastern long-beaked echidnas have five claws on each forefoot, whereas western long-beaked echidnas have three to four claws on each forefoot, usually lacking claws on digits one and five. Skull features also differ. The braincases of eastern long-beaked echidnas are as high as they are is long, whereas western long-beaked echidnas never have braincases as high as they are long. Eastern long-beaked echidnas have smaller orbitotemporal fossae than western long-beaked echidnas and the posterior end of the palate is flattened in eastern long-beaked echidnas, but is a channel in western long-beaked echidnas. Eastern long-beaked echidnas usually have a cranium with a dorsal depression that lies between the rostrum and the braincase. Western long-beaked echidnas lack this feature. However, some eastern long-beaked echidnas lack the depression as well, so this feature is not diagnostic. |=|

Eastern Long-Beaked Echidna Behavior and Diet

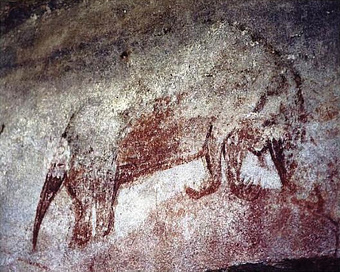

Aboriginal rock art from Arnhem Land in Australia depicting the long, down-curved beak of a long-beaked echidna

Eastern long-beaked echidnas are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary. The home ranges for Eastern long-beaked echidnas are estimated to be 10 to 168 hectares (25 to 415 acres) with a mean of 39 hectares (96 acres). Eastern long-beaked echidnas don’t really face any predators other than humans and their dogs. They may have been hunted by Tasmanian wolves in perhistoric times. Their main predator avoidance strategies are to hide in their underground burrows or roll up in a ball so only their spins are exposed. [Source: Peter Flynn, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Eastern long-beaked echidnas are usually solitary and avoid other echidnas. Their solitary nature makes it hard for researchers to find them and study their behavior. It is known that make underground dens. The burrows made by these in parts of Crater Mountain Wildlife Management Area in Papua New Guinea are generally a mix of dens made in dense vegetation and dens made underground. Studies of captive individuals found that they do not go into a long, deep torpor and thus scientists believe they do not hibernate in the wild. Eastern long-beaked They sense using vision, touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. The skin on the outside of their snout has around 2000 electroreceptors, which allow the animals to detect electrical signals and find prey in the wet soil of their habitat during the night.

Eastern long-beaked echidnas are recognized as carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) but are mostly vermivores (eat worms) and insectivores (eat insects). They forage at night and eat mostly earthworms and occasionally grubs. When foraging for grubs and “wood-boring” invertebrates they tear open logs with their claws. They dig for earthworms using their snout and forelimbs. The “head press” is a probing technique in which they apply pressure to the wet soil, mostly from their long snout and partially from their forelimbs. The depression made by the head press creates a hole, which can be used to find earthworms. Their foraging depressions are larger and deeper than the ones made by short-beaked echidnas. Adaptations for their feeding style include a long snout, relatively large claws on the forefeet and a tongue adapted for grabbing earthworms. There are three rows of sharp, spine-like structures at the back of its tongue, which enables them to more effectively grasp earthworms while foraging. Eastern long-beaked echidnas do not have teeth but they have a horny plate at the back of their mouth to help grind food.

Eastern Long-Beaked Echidna Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Eastern long-beaked echidnas are oviparous, meaning that young are hatched from eggs. They engage in seasonal breeding, breeding once yearly around April or May based on observations of females lactating during these months. The average number of offspring is one. Monotremes lack external genitalia and thus its is difficult to determine sex unless their sex organs come out of their cloaca. When breeding, male penises come out of cloaca, which itself is viewed as a sign of sexual activity. [Source: Peter Flynn, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

According to researchers and local people the reproduction of eastern long-beaked echidnas is similar to that of western long-beaked echidnas and short-beaked echidnas. Local people say said they give birth to one echidna at a time and females lay the eggs that hatch after about 10 days later.

Parental care is provided by females. Young (puugles) are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. The average weaning age is seven months. Like other monotremes, mothers nurse young through pores connected to their mammary glands since they do not have nipples. Juveniles stay in the female’s pouch for six to seven weeks until thir spines grow. Young are weaned after around seven months.

Juvenile Eastern long-beaked echidnas differ from adults is several ways. As they transition to adulthood, the snout lengthens, the sutures of the cranial bones close completely, the posterior palate bones become more robust, the major basicranial foramina stay open but narrow, and the narial opening becomes shorter and rounded posteriorly. The presence of a spur sheath in Eastern long-beaked echidnas are indicative that individuals are juveniles.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Mongabey

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025