Home | Category: Animals / Animals

MONOTREMES

Monotremes: (clockwise from upper left:1) Echidna; 2) Platypus; 3) Long-beakedEchidna; 4) model of a Steropodon (extinct monotreme)

All of the world's monotremes (egg-laying mammals) are found in Australia or New Guinea They are the platypus and four species echidnas. Regarded as "living fossils," they are relatives of early reptile-like mammals called prototherians and are more closely related to reptiles than birds. Monotremes are a different class of mammals than marsupials. Regarded as the ancestors of mammals that preceded all the other mammals living today, they don't have mammary glands with nipples. They instead have patches of skin that "weep" milk. Mammalian features of montremes include body hair and young nourished on milk. Reptilian features include a bare snout and egg-laying anatomy.

“There’s plenty of weirdness to go around on these little things,” Dr. Guillermo W. Rougier, a professor of anatomical sciences and neurobiology at Kentucky’s University of Louisville, told CNN. “They are one of the defining groups of mammals,” Rougier said. “The typical mammal from the time of dinosaurs probably shared a lot more biology with a monotreme than with a horse, a dog, a cat or ourselves.” Therefore, he said, monotremes provide a window into the origins of mammals on Earth. [Source: Amanda Schupak, CNN, May 2, 2025]

Monotremes belong to the order Monotremata. They are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them), but they have unusually low metabolic rates and maintain a body temperature that is lower than that of most other mammals. [Source: Anna Bess Sorin and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

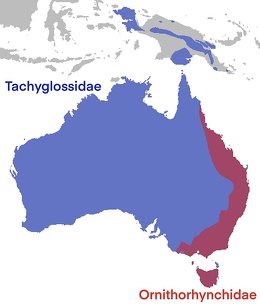

Prototherians are either terrestrial (Echidnas, Tachyglossidae) or primarily aquatic (Platypuses, Ornithorhynchidae). Their terrestrial habitats include deserts, sandy plains, rocky areas, and forests in both lowlands and mountains. Platypuses inhabit lakes, ponds and streams; they shelter in burrows along the banks and spend much of their time foraging in the water. [Source: Matthew Wund; Anna Bess Sorin; Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Monotremes lay leathery, shell-covered eggs. Though they have hair and produces milk, some of their internal organs resemble those of birds and reptiles. They possess one body cavity for the external openings of their urinary, digestive, and reproductive organs. Monotremes are relatively long-lived animals. Echidnas live up to 20 years in the wild and between 30 to 50 years in captivity.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PLATYPUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLATYPUSES AND HUMANS: CONSERVATION, THEFTS, VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com

ECHIDNAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SHORT-BEAKED ECHIDNAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LONG-BEAKED ECHIDNAS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Prototheria

Prototheria is the subclass that contains Monotremes. For all intents and purposed, Prototheria are Monotremes are the same thing except that Prototheria is a broader taxonomic grouping and contains extinct egg-laying mammals as well theas living ones (Monotremes)

The egg-laying mammals are the most ancestral forms in the class Mammalia. According to Animal Diversity Web: Despite bearing fewer species than most mammalian genera, the prototherians are so unique among mammals that there is little question that they represent a distinct and ancient branch of the mammmalian family tree. However, it is not clear how monotremes are related to the two other major lineages of mammals, marsupials (Metatheria) and placentals (Eutheria). Some evidence supports the hypothesis that prototherians form a clade with the marsupials, while other evidence suggests that prototherians are sister to a clade containing both marsupials and placentals. [Source: Matthew Wund; Anna Bess Sorin; Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Evolution of Monotremes

The fossil record Monotremes and Prototheria is very poor; the earliest fossil attributed to this group is from the early Cretaceous (145 million to 100 million years ago). A fossil from Argentina dated to 61 million years ago suggests that the monotremes were more widely distributed early in their history.

Monotremes probably split from the lineage leading to other mammals sometime in the Mesozoic (252 to 66 million years ago). Fossil records provide evidence that mammal ancestors dating back to 220 million years ago were able to suckle based on bone structure and muscle attachment. Monotremes diverged from the mammals around 190 million years ago and therefore lost the ability to suckle. It is hypothesized the loss of the soft palate to allow for sucking occurred as an adaptation to their diet of hard-shelled prey. [Source: Neilee Wilhelm, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Monotremes are often placed in a separate subclass from other mammals, Prototheria. They retain many characters of their therapsid ancestors (for example, a complex pectoral girdle, laying of eggs rather than bearing live young, limbs oriented with humerus and femur held lateral to body, and a cloaca). [Source:Anna Bess Sorin and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

The extinct monotremes Teinolophos, Steropodon and Kollikodon from the Cretaceous period Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago) are considered to be the oldest ancestors of platypuses and echidnas. The remains of Steropodon were discovered in New South Wales, composed of an opalised lower jawbone with three molar teeth ( contemporary platypuses and echidnas are toothless). The fossil jaw of Teinolophos is elongated but unlike that of modern platypuses and echidnas and lacks a beak.

In 2024, Late Cretaceous-aged fossil specimens of early platypus relatives were recovered from the same rocks as Steropodon, including the basal Opalios and the more derived Dharragarra. Dharragarra, which lived between 102 million to 96.6 million years ago, may be the oldest member of the platypus family Ornithorhynchidae, as it retains the same dental formula found in modern platypuses. Monotrematum and Patagorhynchus, fossil relatives of monotremes, are known from the latest Cretaceous (72.1 to 66 million years ago) and mid-Paleocene (61.7 to 58.7 million years ago) fossils from Argentina, indicating that some monotremes managed to colonize South America from Australia when the two continents were connected via Antarctica. [Source: Wikipedia]

100-Million-Year-Old Monotremes

The evolution of monotremes became a little clearer and weirder thanks to clues revealed by a lone fossil specimen that scientists now say represents a long-extinct ancestor. Amanda Schupak, wrote in CNN: A study published May 2025 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences opens that window a little further. Research led by paleontologist Suzanne Hand, a professor emeritus at the University of New South Wales’ School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences in Australia, reveals the internal structure of the only known fossil specimen of the monotreme ancestor Kryoryctes cadburyi, which lived more than 100 million years ago. [Source: Amanda Schupak, CNN, May 2, 2025]

The fossil, a humerus, or upper arm bone, was discovered in 1993 at Dinosaur Cove in southeastern Australia. From the outside, the specimen looked more like a bone from a land-dwelling echidna than a water-loving platypus. But when the researchers peered inside, they saw something different. “By using advanced 3D imaging approaches, we have been able to illuminate previously unseen features of this ancient bone, and those have revealed a quite unexpected story,” said study coauthor Dr. Laura Wilson, an associate professor at Australian National University.

The team found that internally, the fossil had characteristics of the semiaquatic platypus: a thicker bone wall and smaller central cavity. Together, these traits make bones heavier, which is useful in aquatic animals because they reduce buoyancy, so it’s easier for the creatures to dive underwater to forage for food. By contrast, echidnas, which live solely on land, have much thinner, lighter bones.

The finding supports the popular, but unproven, hypothesis that Kryoryctes is a common ancestor of both the platypus and echidna, and that at the time of the dinosaurs, it may have lived at least partially in the water. “Our study indicates that the amphibious lifestyle of the modern platypus had its origins at least 100 million years ago,” Hand said, “and that echidnas made a much later reversion to a fully terrestrial lifestyle.”

There are well-known examples of animals evolving from land to water — for example, it is believed that dolphins and whales evolved from land animals and share lineage with hippos. But there are few examples that show evolution from water to land. The transition requires “substantial changes to the musculoskeletal system,” Wilson said, including new positioning of the limbs for life on land and lighter bones to make moving less energy-intensive.

A land-to-water transition could explain the echidna’s bizarre backward feet, which Hand said it may have inherited from a swimming ancestor that used its hind legs as rudders. “I think that they very elegantly prove the suggestion that these animals were adapted to a semiaquatic life very early on,” said Rougier, who was not involved in the study, though he did have contact with the authors during their research. The primitive history of these unusual animals, he said, is “truly crucial” to our understanding of how mammals (including humans) came to be. “Monotremes are these living relics from a very long distant past. You and a platypus probably had the last common ancestor over 180 million years ago,” he said. “There is no way to predict the biology of this last common ancestor without animals like monotremes.”

Monotremes in Patagonia and What It Means

Patagorhynchus pascuali is the oldest fossil of an monotreme ever discovered in South America. All modern monotremes live in Australia or New Guinea, and a few surrounding islands. Joanna Thompson wrote in Live Science: Millions of years ago, Australia, South America and Antarctica were smooshed together in a supercontinent called Gondwana. This mega landmass began to break up about 180 million years ago, during the Jurassic period, but didn't fully separate until about 66 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period. [Source: Joanna Thompson, Live Science, March 11, 2023]

Because more recent monotreme fossils have been found in South America, scientists previously speculated that the group evolved on the Australian landmass after this continental breakup and later migrated back to South America across a land bridge. But the fact that P. pascuali existed in Argentina before the continental breakup tells a different story. "Our discovery clearly demonstrates that Monotremes didn't evolve uniquely in the Australian continent, but also in other parts of southern Gondwana," study co-author Fernando Novas, a paleontologist at the Bernardino Rivadavia Natural Science Museum in Buenos Aires, Argentina, told Live Science.

The specimen, which was described in the journal Communications Biology on February 16, 2023 was identified by a fragment of a lower jaw containing a molar. When it comes to studying fossilized mammal remains, "teeth give us a huge amount of information," Robin Beck, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Salford in the U.K. who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. In the case of monotremes, though, dental identification is a bit more complicated. "Living platypuses lack teeth," Novas said. But another extinct platypus relative, the 30 million-year-old Obdurodon, retained teeth in both its upper and lower jaws. The P. pascuali molar closely resembled these teeth, as well as the very small, imperfect teeth that baby platypuses briefly possess.

Based on its teeth and apparent habitat, P. pascuali likely had a diet similar to that of a modern platypus: mainly, small aquatic invertebrates, including insect larvae and snails. The Argentinian fossil bed where it was discovered bears this out; Novas said that they found insects and snail shells in the sediments around P. pascuali. Additionally, the researchers uncovered the fossilized remains of other early mammals, turtles, frogs, snakes, aquatic plants and a variety of dinosaurs.

Monotreme Characteristics

Bess Sorin and Phil Myers wrote in Animal Diversity Web: The skulls of monotremes are almost birdlike in appearance, with a long rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth) and smooth external appearance. Modern monotremes lack teeth as adults; sutures are hard to see; the rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth) is elongate, beak-like, and covered by a leathery sheath; and lacrimal bones are absent. Monotremes have several important mammalian characters, however, including fur (but they lack vibrissae), a four chambered heart, a single dentary bone, three middle ear bones, and the ability to lactate. [Source: Anna Bess Sorin and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Besides the absence of teeth, lacrimals, and obvious sutures, monotremes share a number of skeletal characteristics. On the skulls, the jugals are reduced or absent, the dentary is a slender bone with only a vestige of a coronoid process, the angle of the dentary is not inflected medially (unlike that of marsupials), auditory bullae are missing (part of the middle ear is enclosed by tympanic rings), and much of the wall of the braincase is made up by the petrosal rather than the alisphenoid (unlike all other modern mammals).

Postcranially, the skeleton of monotremes is also unique among mammals. It is a fascinating mosaic of primitive characteristics inherited from therapsids but found in no other living mammals, and modifications probably related to the burrowing habits of modern monetremes. Their shoulder girdles are complex, including the standard components of modern mammals (scapula and clavicle), but also additional elements including coracoid, epicoracoid, and interclavicle. The scapula, however, is simplified, lacking a supraspinous fossa (shallow, depressed area on a bone).

The shoulder girdle is much more rigidly attached to the axillary skeleton than in other mammals. Femur and humerus are held roughly parallel to the ground when the animal walks, more in the fashion of therapsids and most modern, reptiles, than like modern mammals. Ribs are found on the neck (cervical) vertebrae as well as the chest (thoracic) vertebrae; in all other modern mammals, they are restricted to the thoracic region.

Another interesting skeletal characteristic of monotremes is the large epipubic bones in the pelvic region. Epipubic bones were originally thought to be related to having a pouch, but they are found in both males and females. They also occur in all species of marsupials, whether a pouch is present or not (not all marsupials have a pouch). It is now thought that epipubic bones are a vestige of the skeleton of therapsids, providing members of that group with extra attachments for abdominal muscles to support the weight of the hindquarters. |=|

Monotreme Behavior, Diet and Communication

Monotremes are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), natatorial (equipped for swimming), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and territorial (defend an area within the home range). They may fall into a hibernation-like torpor or enage in hibernation. Hibernation and torpor are state that some animals enter usually during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal's energy requirements. [Source: Matthew Wund; Anna Bess Sorin; Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

All monotremes are carnivorous, with their diets consisting of various invertebrates. Platypuses forage in the benthos of lakes and streams, using their sensitive bills to find prey. They are generalist predators, whereas echidnas specialize on either ants and termites (Tachyglossus) or worms (Zaglossus). Both species of echidna are powerful diggers and use their claws and snouts to root through the earth to find food. Monotremes are the only mammals (apart from the Guiana dolphin) known to have a sense of electroreception. Playtpuses rely on electrolocation when feeding, as their eyes, ears, and nose are closed while underwater.

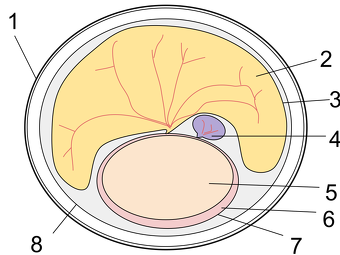

monotreme egg: 1) shell; 2) yolk; 3) yolk sac; 4) allantois; 5) embryo; 6) amniotic fluid; 7) amniotic membrane; and 8) membrane

Monotremes are primarily solitary animals. Echidnas are fully terrestrial and eat mainly ants, termites, and worms whereas platypuses spend much of their time foraging in the water for a wider variety of invertebrates. All species are exceptional diggers, using powerful limbs to dig shelters or to quickly escape from predators. If insufficient food is available, monotremes may enter temporary torpor or more prolonged periods of hibernation when food is scarce in the winter.

Monotremes communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Hearing and sight are well developed in platypuses and moderately well-developed in echidnas. The sense of touch is perhaps most important to a platypus that is searching at the bottom of a stream for food or an echida that is rooting through the earth for termites or worms. Platypus bills and echidna snouts are extremely sensitive organs that are essential to effective foraging. Platypuses may even use electrical stimuli to locate prey. Olfaction is well-developed in echidnas and may be used in individual recognition. Monotremes occasionally produce some simple vocalizations, but their function is unknown. [Source: Matthew Wund; Anna Bess Sorin; Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Monotreme Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

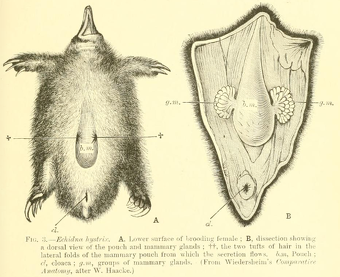

According to scientists at the University of Melbourne and University of Queensland: Monotremes are the only egg-laying mammals, but they also have a number of other unique reproductive characteristics. For the males, their testes never descend, they have no scrotum, when not in use, their penis is stored internally and their ejaculate contains bundles of up to 100 sperm that swim cooperatively until they reach the egg. In most other species, sperm swim individually and it’s every sperm for themselves. Unlike other mammals, the monotreme penis is used only for mating and never carries urine. Among echidna females, in addition to laying an egg, the pouch where they nurse their young is only a temporary structure and develops by the thickening of the lateral margins around the abdominal region that surrounds the mammary glands. [Source: Dr Jane Fenelon and Professor Marilyn Renfree, University of Melbourne, and Associate Professor Stephen Johnston, University of Queensland, Pursuit, June 9. 2021

Little is known about the mating systems of monotreme. They are solitary for most of the year, coming together only to mate. Monotremes are seasonal breeders. Typically, the breeding season lasts one to three months between July and October. Duck-billed platypuses perform somewhat elaborate courtship behaviors prior to copulation. [Source: Matthew Wund; Anna Bess Sorin; Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

During the mating season, duck-billed platypuses are found in pairs, but despite these observations, platypuses are not likely to be monogamous because males do not associate with females post-copulation, nor do they provide any parental care. Female short-nosed spiny echidnas have been observed with several males at a time, which may reflect a polygyny or polyandry. Even less can be inferred about the mating systems of long-nosed spiny echidnas because so little is known about their basic behavior and biology. [Source: Matthew Wund; Anna Bess Sorin; Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Anna Bess Sorin and Phil Myers wrote in Animal Diversity Web: The eggs laid by monotremes are small (13-15 millimeters diameter) and covered by a leathery shell. The number of eggs laid is small, usually 1-3, and they are placed in the mother's pouch. They contain a large yolk, which is concentrated at one end of the egg very much like the yolk of a bird's egg. Only the left ovary is functional in the platypus, but both produce eggs in the echidna. Like the eggs of birds, monotreme eggs are incubated and hatched outside the body of the mother. Incubation lasts about 12 days. [Source: Anna Bess Sorin and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

The young, which are tiny and at a very early stage of development when they hatch, break out of the eggs using a "milk tooth. They are protected in a temporary pouch in echidnas but not platypuses. They are fed milk produced by mammary glands; the milk is secreted onto the skin within the pouch and sucked or lapped up by the babies. Weaning takes place when the young are 16-20 weeks old. All male monotremes have spurs on their ankles that are presumed to be used in fighting and in defense. Platypuses have a groove along the spur carries poison secreted by adjacent glands.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025