PLATYPUS CONSERVATION

Syd the platypus along with Olly the kookaburra and Millie the echidna — mascots of the 2000 Olympics in Sydney

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, platypuses have been listed as "near threatened" since in 2016, based on estimates that their numbers had fallen by about thirty percent on average since the arrival of Europeans in the 18th century. Some biologists believe the estimates of the 2016 numbers are inaccurate and their numbers may have declined by as much as fifty percent.

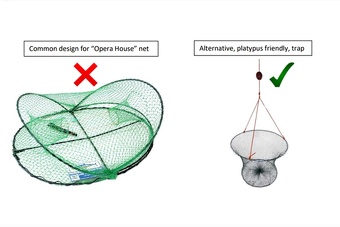

The main threats to platypuses are loss and degradation of their aquatic habitat by dams, pollution, urban expansion, and urban runoff. Droughts and the demands for water for human use are also considered threats. Some platypuses drown in nets of inland fisheries. The use of "opera house traps" by recreational fishers for catching crawfish is banned in South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria, and restricted in NSW and Queensland, due to the traps drowning non-targeted species including platypuses.

Platypus skins were harvested by fur traders to make hats, slippers, and rugs but this practice officially ended by a law passed in 1912 that protected platypuses from being hunted. Platypus have fallen prey to a disease producing skin lesions and attacking internal organs, Predators of platypuses include foxes, humans, and dogs. Others are snakes, birds of prey, feral cats, and large eels.

Estimates on the current population of platypuses range from 30,000 to around 300,000, according to Reuters. A 2020 survey by researchers at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. university found that platypus habitat in eastern Australia shrunk by about 22 percent between 1990 and 2020 because of land clearing, droughts and river regulation.

Studying platypuses is difficult. They are difficult to find and easily disturbed by noises near their burrows. They leave few traces such a tracks, feces, or food scraps, because they spend most of their time in the water. Scientists who study them catch platypuses in tubular nets, weigh the animals, implant a microchip so they ca be identified if caught later and then released. Platypuses are also difficult to study in laboratories and rarely seen in zoos because they are difficult to keep alive in captivity.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MONOTREMES: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLATYPUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ECHIDNAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SHORT-BEAKED ECHIDNAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LONG-BEAKED ECHIDNAS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Platypuses and Aboriginals

Aboriginal Australians hunted and ate platypuses, particularly for their fatty nutritious tails in the the past. In some Aboriginal Dreamtime stories platypuses were described as hybrid of a duck and a water rat. Aboriginals from the upper Darling River region have a story of a large water-rat called Biggoon who kidnaps a duck what wandered too far from its tribe. After managing to escape, she returned and laid two eggs which hatched the first platypuses. They were all exiled and went to live in the mountains. In another story from the upper Darling, the major animal groups, the land animals, water animals and birds, all competed for the platypus to join their respective groups, but the platypus ultimately decided to not join any of them, feeling that he did not need to be part of a group to be special, and wished to remain friends with all of those groups. The platypus is also featured as a totem for some Aboriginal peoples, such as the Wadi Wadi people of the Murray River, who viewed them them as "a natural object, plant or animal that is inherited by members of a clan or family as their spiritual emblem".

Platypus Wandering From Terra Nova Gallery

One Aboriginal creation story about the origin of the platypus, Mathew Crowther wrote in The Conversation, goes: During the Dreaming, Tharalkoo was a head-strong duck inclined to disobey her parents. Her parents warned her not to swim downriver because Bigoon the Water-rat would have his wicked way with her. Scoffing, she disobeyed her parents and was raped by Bigoon. By the time Tharalkoo escaped and returned to her family, the other girl ducks were laying eggs, so she did the same. But instead of a fluffy little duckling emerging from her egg, her child was an amazing chimera that had the bill, webbed hind feet, and egg-laying habit of a duck, along with the fur and front feet of a rat. It was the first platypus. [Source: Mathew Crowther, Senior Lecturer in Wildlife Management, University of Sydney, The Conversation, November 4, 2013]

Australian Aboriginal people have referred to platypuses using various names depending on the region, language and dialects. Among the names found: 1) boondaburra, mallingong, tambreet, watjarang (used by Yass, Murrumbidgee, and Tumut); 2) tohunbuck (used in the Goomburra, Darling Downs region); 3) dulaiwarrung or dulai warrung (in the Woiwurrung language, Wurundjeri, Victoria); 4) djanbang (Bundjalung, Queensland); 5) djumulung (Yuin language, Yuin, New South Wales); 6) maluŋgaŋ (ngunnawal language, Ngunnawal, Australian Capital Territory); 7) biladurang, wamul, dyiimalung, oornie, dungidany (Wiradjuri language, Wiradjuri, Vic, New South Wales); and 8) larila (in Palawa kani, the reconstructed Tasmanian language).

Platypuses and Europeans

The unique features of platypuses make them important in the study of evolutionary biology. They are an important symbol of Australia and have appeared on stamps, currency, the 20 cent coin and as a mascot in the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney. Platypuses culturally significant to several Aboriginal peoples, who also used to hunt them for food and recognized in their dreamtime beliefs.

When a stuffed platypus was first shown in Europe in 1768 people thought it was hoax like a unicorn or dragon. They believed somebody had glued the bill and webbed feet of a duck and the flat tail of a beaver onto a small dog. It wasn't until 1884 when the first platypus eggs were discovered that scientist accepted that the platypuses really existed

Europeans killed platypus for fur from the late 19th century until they practice banned in 1912. After this European researchers captured and killed platypuses or removed their eggs in order to increase scientific knowledge, but also to gain prestige and outcompete rivals from different countries. During the Second World War, in spite of an export ban, Australia gave live platypuses as diplomatic gifts to Allied nations as part of an initiative to increase military assistance. One which was intended as a gift to Winston Churchill died from neglect while en route. [Source: Wikipedia]

Platypuses are currently protected by the Australian government. Populations are considered healthy in some place; less so on other places. Captive breeding and release programs have had some successes but nothing major.

Platypuses in Urban and Suburban Environments

Platypuses live in urban and suburban environments around Melbourne. In the early 2000s, half the waterways in greater Melbourne contained platypuses and had been found in the Yara River 16 kilometers (ten miles) from downtown Melbourne. The Melbourne city water department improved the conditions of platypus habitats by repairing eroded stream channels as wells as educating the public about what they can do too help platypuses. Around 10 percent of platypuses found in the Melbourne area had things like fishing line or six-pack holders entangled around them. The sometimes die from infected cuts or their legs become so entangled so they can't swim.

According to Australian Platypus Conservancy. he Tpresence of trees and other vegetation encourages rain to filter into the soil before gradually flowing downhill to streams and rivers. Replacing soil and plants by hard surfaces (such as roofs and roads) encourages rain runoff to run much more rapidly to the nearest stream or river, especially if it travels through an impermeable stormwater drain or pipe. In turn, this promotes bank and channel erosion and reduces flow in the channel between storms. It also carries a wide range of pollutants into waterways, including grease and oil from roads, litter, and toxic metals from many sources, including metal roofing (zinc), tires (zinc and cadmium) and wear of other car parts (chromium, nickel and copper). This suite of noxious impacts has been aptly characterised as “urban stream syndrome” (Walsh et al. 2005).

The platypus is correctly described as being sensitive to urban development. Furthermore, based on sophisticated modelling, adult females disappear more quickly from urban water courses than males, presumably because a female platypus’s home range must be productive enough to support both her and her developing offspring.

Platypuses Return to Australian National Park 50 Years after They Disappeaed

In May 2023, platypuses were reintroduced by Royal National Park — Australia’s oldest national park — south of Sydney by scientists from the University of New South Wales, Sydney. Platypuses were once plentiful in the park but had not been seen there since the 1970s. Moira Ritter wrote in the Miami Herald: Four female platypuses were released on the banks of the park’s Hacking River, the university said. The platypuses are the first batch of what will eventually be a group of 10 including four males and six females. [Source: Moira Ritter, Miami Herald, May 17, 2023]

Experts hope by introducing the group of 10, they can create a self-sustaining population of platypuses within the park. “We really want platypus to be the new sentinels of our rivers. If your platypuses are doing well, the river is probably in pretty good shape,” Richard Kingsford, director of the Centre for Ecosystem Science and member of the UNew South Wales platypus research team, said in the university’s release. “It is fitting that we should be returning this top river predator to its right place,” Kingsford said in the release. “Exciting reintroductions like this provide a focus for monitoring management and learning how to deliver for conservation.”

The creatures were collected from various sites in southern New South Wales that have more established platypus populations, researchers said. “The welfare of the platypuses was always our highest priority — both at the source sites and the release site at Royal National Park,” Tahneal Hawke, a researcher who worked on the project, said in the release. “We collected platypuses from multiple sites across multiple rivers to ensure no impacts to the source populations, and to ensure genetic diversity of the introduced population at Royal National Park.”

Conservationists aren’t sure exactly why platypused disappeared from the rivers of Royal National Park. It could have been due to a chemical tanker spill on the nearby Princes Highway or excessive predation by foxes or cats, the Good News Network reported. Each of the reintroduced platypus was tracked for two years to see how they responded to events like drought.

Man Arrested After Showing Off a Platypus on Train

In April 2023, an Australian man was arrested after allegedly stealing a platypus from the wild, taking it on a train and then showing it off at local shops. According to the BBC: The 26-year-old man was located after police appealed for public help to find the animal — for which they have grave health concerns. Queensland Police were told the mammal had been released in a nearby river but haven't been able to locate it. The arrested man has been charged with taking an animal classified as protected from the wild and keeping a protected animal captive. He could face a fine of up to US$288,500). [Source: Tiffanie Turnbull, BBC, April 6, 2023]

A woman who was with him has also spoken to police. Surveillance cameras captured the pair boarding a train at Morayfield, about an hour north of Brisbane, holding the animal wrapped in a towel. "According to the report that was provided to [authorities], they were showing it off to people on the train, allowing people to pat it," Queensland Police's Scott Knowles said.Police will also allege in court that the pair were seen showing the animal to members of the public at a nearby shopping centre.

Queensland's environment department had stressed that the platypus was at risk of sickness or death the longer it remained out of its habitat, and urged the pair to take it to a vet. Police said they were advised the platypus had been released into the Caboolture River, but said they were unsure of its condition. In a statement, police said it was risky behaviour for both the humans and the animal. "Taking a platypus from the wild is not only illegal, but it can be dangerous for both the displaced animal and the person involved if the platypus is male as they have venomous spurs," it said. "If you are lucky enough to see a platypus in the wild, keep your distance. Never pat, hold or take an animal."

Woman in Excruciating Pain After Being Stabbed by the Spurs of a Platypus

In October 2023, a platypus wandering on a roadside in Australia stabbed a woman with its venomous spurs when she attempted to lift it from a gutter. Emily Cooke wrote in Live Science: Jenny Forward was driving home in Tasmania when she spotted what she thought was an injured platypus on the roadside. She attempted to intervene, but when she picked up the semi-aquatic critter, she felt two spikes dig into either side of her right hand. These spikes released venom into the wounds, leaving her in agony, ABC News reported."It was as though someone had stabbed [my hand] with a knife," Forward told the news network. "The pain was excruciating … definitely worse than childbirth," she said. [Source: Emily Cooke, Live Science, October 14, 2023]

After quickly removing the platypus' spurs from her flesh, Forward drove to the hospital, where doctors gave her antibiotics and pain relief. They then conducted emergency surgery to clean and stitch up her wounds. A week after treatment, Forward was still in pain and had red swelling on her hand, ABC News reported.

Male platypuses have hollow spurs on their back legs linked to glands that produce a clear, sticky venom. The animals' venom production peaks during their mating season, which normally begins towards the end of winter, so scientists think it's a weapon that's normally used to compete with other males for access to females, according to the Australian Platypus Conservancy (APC).

Platypus venom is not life-threatening to humans or other platypuses, but it can cause intense pain and swelling in the part of the body where someone is spurred. Studies on platypus venom are limited, but research suggests it contains a mixture of small proteins, such as Heptapeptide 1, which targets the nervous system, and an enzyme called amine oxidase that may trigger cell death and tissue swelling.

There is no approved antivenom, but nerve-blocking drugs, such as bupivacaine, can be used to minimize the pain from a platypus spurring you, the APC said in a Facebook post addressing the woman's recent stabbing. People may assume that if they see a platypus on land or near a drain that they are in danger when this may not always be the case, Greg Irons, director of the Bonorong Wildlife Sanctuary in Brighton, Australia, told ABC News. "Platypus will travel fairly long distances on land and they also use drains as highways," he said.

If someone sees a platypus in the wild and they're unsure of whether it needs help, Irons recommended taking a video or photo of the animal and sharing it with a wildlife rescuer. If it looks obviously injured, then you could also place a tub over it to protect it while you wait for help, he said. On Facebook, the APC noted that male platypuses are rarely aggressive if handled correctly. Rather than placing a hand under the animal, trained animal caretakers would lift the platypus from the middle or end of its tail to avoid the spurs.

Platypus, Echidna Venom Could Help Treat Diabetes

In December 2016, in a study published in Nature’s online journal Scientific Reports, Australian researchers announced that they had discovered that a hormone produced in both platypus and echidna venom could hold the key to treating type-2 diabetes. Sofia Charalambous wrote in Australian Geographic: Research led by Professor Frank Grützner at the University of Adelaide and Associate Professor Briony Forbes at Flinders University in Adelaide has revealed that a hormone usually produced in the gut of both humans and animals is actually also found in the venom of Australia’s iconic monotremes, the platypus and the echidna.[Source: Sofia Charalambous, Australian Geographic, December 6, 2016]

The hormone, known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), is produced by all animals to stimulate the release of insulin to lower blood glucose. Typically, it degrades pretty quickly and because of its short life span, it’s not sufficient for maintaining a proper blood sugar balance for people with type-2 diabetes. Medication with a longer-lasting form of the hormone is needed to provide an adequate release of insulin. However, GLP-1 works a little differently in monotremes. New findings in the study published Scientific Reports revealed that GLP-1 in platypus and echidnas appears to have evolved resistance to the normal degradation seen in humans and other animals. The researchers also found the hormone appears both in the gut and the venom of these animals.

The platypus produces venom during breeding season in order to ward off other males when competing for females. Because GLP-1 is an element of the venom being used by competitors, the platypus must develop resistance to the hormone in order to protect itself, as well as continue to process the hormone for its normal function in the gut. “Our analysis indeed found signatures of this tug of war between the normal function in gut and the novel function in venom,” Frank explained.

Dr Tom Grant, an expert in the ecology and biology of the platypus from the University of New South Wales who was not involved in this research, has commented on the unexpected discovery, acknowledging the potential benefits of the findings. “It obviously has possible implications for the management of human type-2 diabetes, once it has tested in animal models,” he said. “As well as this, however, the research gives us further insight into the different molecular evolution in our unique egg-laying mammals.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025