Home | Category: History and Exploration

MAGELLAN

Ferdinand Magellan (1480?-1521) was the leader of a group of sailors that the circled the globe in the early 16th century, an amazing feat that perhaps will not be equaled until a human being lands on Mars. Magellan himself did not complete the trip. Of the 300 or so men and five ships that left Portugal with Magellan only one ship made it back to its embarkation place and only 18 men made it back there alive.

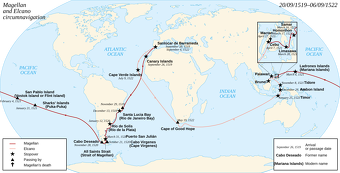

Magellan sailed the Pacific East to West on a Spanish (Castilian) expedition of world circumnavigation starting in 1519. That year he sailed down the east coast of South America, found and sailed through the strait that bears his name. In November 1520, he entered the Pacific. Magellan then sailed north and caught the trade winds which carried him across the Pacific. In a vivid illustration of the emptiness of the Pacific, Magellan sailed across the entire ocean before touching land in the Mariana Islands of western Micronesia in 1521. After Magellan was killed in the what is now the Philippines, one surviving ship went west across the Indian Ocean and the other went north in the hope of finding the westerlies and reaching Mexico. The Pacific was often called the Sea of Magellan in his honor until the eighteenth century.

"No other had so much natural wit, boldness, or knowledge," is how one man described Magellan. W said he was an "able and ruthless" Portugese soldier-adventurer-seaman with battle-lame leg. "Magellan's feat," wrote historian Daniel Boorstin, "by any measure — moral, intellectual, or physical — would excel even that of Gama or Columbus or Vespucci. he would face rougher seas, negotiate more treacherous passages and find his way across a broader ocean.”

Compared to what Magellan accomplished, Columbus’s journey was a ride to the park. Columbus followed sunny trade winds to the West Indies and followed the prevailing westerlies back to Europe. Magellan on the other hand traveled about ten times the distance Columbus did: through the crushing winds in the furious fifties latitudes of southern South America and icy seas of north of Antarctica, then traveled across the breadth of the Pacific (a distance about four times what Columbus traveled across the Atlantic), having absolutely no idea where land was or where he was going. Once he achieved that feat he was only halfway home. His objective was cloves and other cooking spices in the Moluccas, or Spice Islands.

Related Articles: SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com ; EUROPEANS DISCOVER THE PACIFIC AND OCEANIA ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA BY EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN THE PACIFIC: DESCRIPTIONS, EVENTS AND PLACES VISITED ioa.factsanddetails.com ; FIRST EUROPEAN IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, SETTLERS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com EUROPEANS IN THE PACIFIC IN THE 1800S: WHALERS, MISSIONARIES, COPRA AND FORCED LABOR ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR AND ITS IMPACT ON THE NORTHERN PACIFIC factsanddetails.com

Magellan's Early Life

Ferdinand Magellan was born to a noble family in a part of Portugal with a climate described as "nine months of winter and three months of hell." He was orphaned at an early age and grew up as a page in the Portuguese court at a time when Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope and de Gama (both Portugese) made it to India.

In 1505, at the age of 25, he sailed to India where he served under Alfonos Albuquerque, founder of the Portuguese empire in Asia, and explored as far east as the Spice Islands (Moluccas) in present-day Indonesia. When he returned to Portugal in 1512 he had attained the rank of captain. He was lamed for life while fighting the Moors in Northern Africa and later fell out of favor with Portugese court and moved to Spain.

To gain support for his plan to sail west to the West Indies by locating a westward passage at the southern tip of South America, Magellan married the daughter of Portuguese expatriate who made decisions regarding Spanish voyages to the west. The union helped seal a deal that gave Magellan and a partner one twentieth of all the profits of their voyage and their heirs would be given the governorship to all new lands discovered. [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Discoverers"]

Purpose of Magellan's Voyage

The main reason Magellan circled the globe was to determine where the dividing line between Spain and Portugal — set up by the Treaty of Tordesillas — was. The Treaty of Tordesillas divided the New World between Portugal and Spain. Signed in 1494, the agreement gave Spain all the land to the west of a meridian 370 degrees west of the Cape Verde Islands (off Africa), and the land to the east to Portugul. This agreement is why Brazil ended up being Portuguese and the rest of Latin America became a Spanish possesion.

The line dividing Spanish and Portuguese territory ran 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands on the Atlantic side (46°longitude) and 134° longitude on the Asian side, but nobody knew exactly where that was. With the Treaty of Saragossa in 1529, the Portuguese payed Emperor Charles V of Spain 350,000 ducats of gold (a huge sum of money at that time) to gain possession sole of the Spice Islands. When chronometers were invented they showed that the land was in fact on the Portuguese side anyway. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992]

Like Columbus, Magellan was also seeking a western route to Spice Islands in Asia, but by this time he knew there was a continent in the way and he was determined to get around it. The expedition was financed by the Spanish king (the Portuguese king had refused to back him). Most of the officers were Spanish. Two-and-a-half years before he set off Magellan himself changed his nationality and became a Spaniard.

Magellan's Ship and Crew

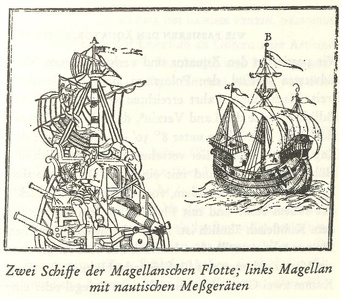

Victoria, the sole ship of Magellan's fleet to complete the circumnavigation; Detail from a map by Ortelius, 1590

Magellan sailed with 300 men and five heavily armed but "barely seaworthy" ships (varying in size between 75 and 125 tons). The largest ship was smaller than the Mayflower, which in turn was smaller than a modern tug-boat.

The ships were supplied with trading goods such as brass bracelets, 500 looking glasses, bolts of velvet, 2,000 pounds of quicksilver and 20,000 hawkbells to barter for spices. Unknown to Magellan was that his suppliers had short-changed him on supplies. He didn't realize that he had been given six months of supplies — instead of the year and a half he agreed to — until he was about to go through the Strait of Magellan

Magellan's 250 man crew consisted mainly of foreigners — Portuguese, Frenchmen, Italians, Greeks and Englishmen — because Spaniards were reluctant to embark on such a risky voyage with a foreign captain. The three Spanish captains who accompanied Magellan were suspicious of him from the start and they may have made plans to make sure he didn’t finish the voyage. [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Discoverers"]

Pigafetta’s Descriptions of Magellan’s Voyage

Most of the details we know about Magellan’s voyage come from Magellan's log and a journal by one of his crew members, Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian gentleman-adventurer who "came along for the ride." His account of the voyage is one of most of the insightful and vividly written reports in the Age of Discovery. Luckily he was one of the handful of men that finished the voyage. "I am determined," the Italian Knight of Rhodes wrote, "to experience and to go...that it might be told that I made the voyage and saw with my eyes the things hereafter written and that I might win a famous name."

Pigafetta's closest brush with death occurred when he fell off a ship but luckily caught a line after he cried for help. It seems he couldn't swim. About sharks Pigafetta wrote: "great fish called 'Tiburoni' approached the ships. They have terrible teeth and eat men...and even the small ones are not much good [as food]. He also described electrostatic effect known as St. Elmos' fire.

"Among the other virtues which he possesses, Pigafetta wrote about Magellan, "he was always the most constant in greatest adversity...he endured hunger better than all the rest and more accurately than any man in the world, he understood dead reckoning and celestial navigation. No other had so much talent, nor the ardor to learn how to go around the world which he almost did."

First Leg of Magellan's Voyage — Along the East Coast of South America

The route of the Victoria, which completed the world's first recorded circumnavigation over about 3 years

Magellan and his ships embarked from the Spanish port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda on September 20, 1519. Their first destination was the Canary islands. Four months from Spain and two months from the Canaries, Magellan crossed the Atlantic and reached the eastern tip of Brazil. he followed the coast southward and traded for supplies in a port called Verzin, latter renamed to Rio de Janeiro. In his log he wrote: "The men and women of this place are of good physical build."

At the Río de la Plata, a large bay or marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean near present-day Buenos Aires, Argentina, Magellan thought he found a passage to the Pacific Ocean. But realized that was not the case after tasting the water and finding it was not very salty. After investigating several bays and rivers that turned out to be dead ends, Magellan decided the spend the South American winter of 1520 in St. Julian Bay, located about 1,100 kilometers (700 miles) south Buenos Aires.

"One day," Pigafetta wrote, "we saw a giant who was on the shore...So tall was this man that we came up to the level of his waistbelt. he was well enough made and had a broad face, painted red. His hair cut short and shaved like friars, and colored white, and he was dressed in skins.

The "giants" had huge feet (or perhaps thick-grass wrappings around them) reported Magellan who named them “Patgonians “(Spanish for "people with big feet") and their land Patagonia. The Portuguese captain gave these people "a mirror, a comb, bells, and other things" and then kidnapped "the two youngest to bring them to Spain."

Mutiny of Magellan's Journey

Magellan crew didn’t like it in Patagonia. Most of them wanted to return to tropical ports in the north but Magellan worried that if they did that they might loose valuable time and the crew might lose their resolve to carry on and he decided to go on short rations and wait until the spring to resume his journey.

One of the deciding moments of Magellan's voyage came on April 1, 1520. Docked in a bay in Patagonia and not very close to their destination after six months and 10,000 kilometers (6,000 miles) of traveling at sea, Magellan's crew decided to mutiny. The operation began when Magellan invited the captains and officers on the four other ships to dine on his ship (the “Trinidad”) and not one of them showed up. Instead they sent a boat to his ship, announcing the independence of three of the ships. Magellan didn’t stand for this. He sent a messenger to the cabin of the fleet treasurer, Luis de Mendoza, and told him to immediately report to Magellan's ship. When Mendoza responded with a sneer and laugh, the messenger, following his captain’s orders, grabbed the Spaniard by the throats and slit his throat with a dagger.

At about the same time a boatload of Magellan's men leaped aboard one of the other ships, whose captain Gaspar de Quesada was placed in irons. Magellan himself led an assault on a third ship that was trying to escape and its captain Juan de Cartegena was captured, bringing the mutiny to an abrupt, decisive end.

Only two en were killed in mutiny and two men were left behind. To prevent any one from getting any more ideas "The treasurer," Magellan wrote in his log, "was...quartered...Caspar Quesada had his head cut off, and then he was quartered...And Juan de Cartagena...was banished.. and put in exile on that land called “Patagonia”. A month after this one of the ships was lost while surveying a coastal passage, but "all the men were saved by a miracle," wrote one his officers, for they were not even wetted."

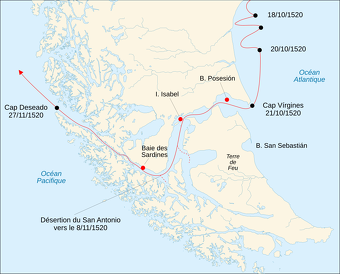

Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan, also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile and Argentian separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. It was navigated by canoe-faring indigenous peoples including the Kawésqar for thousands of years. In 1520, Magellan, after whom the strait is named, became the first Europeans to discover it. Magellan's original name for the strait was Estrecho de Todos los Santos ("Strait of All Saints"). The King of Spain, Emperor Charles V, who sponsored the Magellan-Elcano expedition, changed the name to the Strait of Magellan in honor of Magellan.

The route is difficult to navigate due to frequent narrows and unpredictable winds and currents. Maritime piloting is now compulsory. The strait is shorter and more sheltered than the Drake Passage, the often stormy open sea route around Cape Horn, which is beset by frequent gale-force winds and icebergs. Along with the Beagle Channel, the strait was one of the few sea routes between the Atlantic and Pacific before the construction of the Panama Canal.

"To say that the strait through the American land barrier was 'well hidden' turned out to be the understatement of the centuries," wrote Boorstin. "The Strait of Magellan — the narrowest, most devious, most circuitous of all straits connecting two great bodies of water — was a wonderful ironic prop for a seafaring melodrama...We must view on a modern map the tortuous passage, the angular disorder of islands, the countless unexpected slots of water, to grasp the full measure of expertise, the persistence, courage — and luck — required to find the way."

"While the entrance at Cape Virgins on the Atlantic side goes through mild and pleasant country with low grassy banks, the exit on the Pacific is a gargantuan fjord between craggy ice-capped mountains...Some of the narrows were less than three kilometers (two miles) wide, The passage so meandered, with countless misleading bays and rivers, that not until the end was there any view of open sea. To sail the 585 kilometers (364 miles) between the oceans took Magellan 38 days. Drake’s 16 days would be the 16th century record, others would take more than three month, many would simply give up.

Great winds known as williwas blasted the western side of the straits. An English captain in 1900 wrote: "These were compressed gales of wind that Boreas handed down over the hills in chunks. A full-blown williwaw will throw a ship, even without sail set, over her on her beam end."

Magellan Journey Through the Strait of Magellan

It took Magellan 38 days to traverse the Strait of Magellan. Compared to experience that mariners have had since Magellan had a rather easy go of it. Uncharacteristically the winds were light and there was plenty of good water in the streams on the shores and sardines for eating in the sea.

"After going...to the fifty-second degree [of latitude]," Pigafetta wrote, "toward the said Antarctic Ole, on the festival of the eleven thousand virgins [October 21]. Which strait is in length one hundred and ten leagues [a league is roughly three miles]...And it falls into another sea called the Pacific Sea. And it is surrounded by very great...mountains covered with snow."

Magellan entered the Strait of Magellan with four ships and left with three. Traversing the waterway, two ships went ahead, picking out good routes though difficult passages and locating good anchorages. During one these scouting trip one of the ships didn't return. The pilot on this ship overpowered the captain, doubled back during the night, and headed home to Spain. This left three of the original five ships. The leader of the mutiny hated Magellan and when he returned to Spain he accused Magellan of all sorts of things and spent only a short time in jail for a crime which is punishable by death. When Magellan asked his astrologer what had happened, he consulted the stars and gave an accurate report of what really happened.

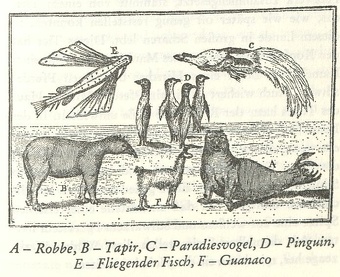

Short on supplies, Magellan's crew tried to catch fish, sea birds and guanacos for food. Fresh water was difficult to obtain, with the shores being difficult to approach, and the crew suffered terribly. When a scouting boat finally spotted the open sea Pigafetta wrote "the captain-general wept for joy, and called that cape, cape Dezeado [Desire], for we had been desiring it for a long time." So impressed by Magellan's skill was Pigaetta that he thought he may have seen a secret map of the route "in the treasury of the King of Portugal."

The voyage through the Strait of Magellan also answered the question once and for all about a passage to the Orient — the Cape of Good Hope route around Africa was much better.

Magellan's Journey Across the Pacific

By far the most harrowing part of Magellan’s journey was from the Strait of Magellan across the Pacific. Neither Magellan or his crew had any idea what lay ahead and Magellan thought at most the journey would take a couple of weeks. . No European had ever been in this part of the world before and no one knew how wide the Pacific was — for a, accurate system of longitude had not yet been devised.

"We issued forth from the said strait and entered the Pacific Sea," wrote Pigafatta, "where we remained for three months and twenty days without taking on board provisions or any other provisions or any other refreshment."

Magellan was blessed with unusually good weather across the Pacific, thus the name. "In truth," Magellan wrote, the sea "is very pacific, for during that time we did not suffer any storm." This lead the misleading name of the ocean — the Pacific.

The only land they encountered were "two small uninhabited islands where we found only birds and trees. Wherefore we called them the Isles of Misfortune...We found no anchorage, [but] near them, saw many sharks. And if our Lord and his blessed Mother had not aided us by giving good weather we would all have died of hunger in that exceeding vast sea.

To take full advantage of the wind Magellan could sail well directly from the straits he had to sail north along the South American coast to catch the prevailing northeasterly trade winds to the west. The course he took is still recommended by the United States Government Pilot Association for sailors heading from cape Horn to Hawaii.

Hardships in the Pacific

Magellan's crew was unable to catch many fish, except for albacore they dispatched with a "barbed hook in a piece of white rag secured to a chip of wood." Occasionally a flying fish inadvertently flew onto the deck and rain squalls were their only source of water. In the Doldrums (an area in sea with no wind) the crew had to hold their nose to drink the putrid water stored in the hold. The men were so weak from lack of food and water it took six or eight men to perform work that only took one.

"We ate biscuit, which was no longer biscuit, but powder of biscuits swarming with worms, for they had eaten the good. It stank strongly of the urine of rats. We drank yellow water that had been putrid for many days. We also ate some ox hides that covered the top of the mainyard...We left them in the sea for four of five days, an then placed them for a few moments on top of the embers, and so ate them; and often we ate sawdust from boards. Rats sold for one-half ducado a piece and even then we could not get them.

“But above all the other misfortunes the following was the worst. The gums of both the lower and upper teeth of some of our men swelled, as they could not eat under any circumstances and therefore died. Nineteen men died from the sickness, and the [Patagonian] giant together with an Indian from the country of Verzin." This disease of course was scurvy, and it claimed 29 members of the crew.

Magellan in Guam

On March 6, 1521, Magellan's three ships finally reached Guam, 14,500 (9000 miles) from Patagonia, and a considerable distance to the north as well as west. In Guam the seamen were able to load up on sugarcane, rice, fish, bananas and yams. Fruit with Vitamin C to relieve the scurvy was especially heaven-sent. Because the local Chamorro people swarmed all over the ship and grabbed everything they could their hands on, Magellan named Guam and the islands around it the Ladrones (Spanish fro "thieves").

The Chamorro people who came aboard the ships took items such as rigging, knives, and a ship's boat. They were particularly fond of nails and other metal item from their boat, because they yet to learn how to smelt metal themselves. They may have thought they were participating in a trade exchange (as they had already given the fleet some supplies, but the crew interpreted their actions as theft. Magellan sent a raiding party ashore to retaliate, killing several Chamorro men, burning their houses, and recovering the stolen goods.

Describing the inhabitants of Guam, Antonio Pigafette wrote: "the people of these islands boarded the ships and robbed us, in such a way that it was impossible to preserve oneself from them. Whilst we lowering the sails to go ashore, they stole away with much address and diligence the small boat called the skiff, which was made fast to the poop of the captain's ship, at which he was much irritated, and went in shore with forty armed men, burned forty or fifty houses, with several small boats, and killed seven men of the island; they recovered their skiff."

After three days in Guam, Magellan sailed west and reached the Philippine islands of Suluan and Samar in a week. Here sailors with scurvy were sent ashore to recuperate, and hawbells, red caps and mirrors were traded for coconuts and bananas (refered to as "figs a foot long" by Pigafetta). When a chief showed up with a bar of gold and a basket of ginger the captain thanked him very much but would not accept the present. After that, when it was late, we went with the ships near to the houses and abode of the king.”

Magellan in the Philippines

Magellan landed on Homonhon Islet (Limasawa Island), near Samar Island in the present-day Philippines, at dawn on March 16, 1521. He claimed the islands for Spain and named them the "Islas de San Lazaro" (St. Lazarus' Islands) because he arrived at the archipelago on the feast day of Saint Lazarus of Bethany. Under Magellan, the Philippines first Catholic mass was held on April 14, 1521 on Cebu, where he planted a cross on the spit where a local ruler was converted along with the 800 of his people. Local believed that the cross possessed magical powers and over the centuries that followed took pieces of it

Magellan spent about a month in the Philippines. He was welcomed to the islands of Samar, Leyte, and Limasawa. Within a week of arriving on Cebu he converted 400 islanders including Humabon and Juana, the island's king and queen. Professor Susan Russell wrote: “Magellan's arrival in Cebu represents the first attempt by Spain to convert Filipinos to Roman Catholicism. The story goes that Magellan met with Chief Humabon of the island of Cebu, who had an ill grandson. Magellan (or one of his men) was able to cure or help this young boy, and in gratitude Chief Humabon allowed 800 of his followers to be 'baptized' Christian in a mass baptism. [Source: Professor Susan Russell, Department of Anthropology, Center for Southeast Asian Studies Northern Illinois University, seasite.niu.edu]

Magellan was killed on Mactan Island off Cebu Island by a local leader named Lapu Lapu. A plaque on Mactan reads: "Here Lapu Lapu and his men repulsed the Spanish invaders, killing their leader, Ferdinand Magellan, Thus Lapu Lapu became the first Filipino to have repelled European aggression." Of the 300 or so men that left Portugal with Magellan on his ship only 14 made it back alive.

Lapu Lapu is an enduring cultural hero in the Philippines. His defeat of Magellan has been immortalized in movies, comic books and popular songs. Every year the triumphant defeat of the Spanish is reenacted on the island of Mactan. Russell wrote: Lapu Lapu’s “resistance to Western intrusion makes this story an important part of the nationalist history of the Philippines. Many historians have claimed that the Philippines peacefully 'accepted' Spanish rule; the reality is that many insurgencies and rebellions continued on small scales in different places through the Hispanic colonial period.”

See Separate Article: MAGELLAN IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Magellan Crew in Indonesia

After Magellan was killed in the Philippines in 1521 his crew continued on to the Spice Island. At this point in the voyage Magellan's crew still had 17,770 kilometers (11,000 miles) to go to get home. By this time only 100 of the 250 men that left South America remained, and one the three remaining ships was so filled with worm holes that these men decided to squeeze onto to the remaining two ships.

Instead of sailing the short distance between Cebu and the Spice Islands the ships took a more circuitous route, stopping first in Borneo where they encountered an Arab outpost near present-day Brunei. This was their first contact with a race of people of which the new since they left Brazil.

A couple of months later they reached the Spice Islands where the two ships loaded up with cloves. At that time nutmeg and cloves were worth more than gold. "When the cloves sprout," wrote Pigafetta, "they are white; when ripe, red; and when dried, black...Nowhere in the world do good gloves grow except on five mountains of those five islands."

One of the overfilled ships sprang a leak and had to be unloaded again for repairs. The other ship, captained by Juan Sebastián del Cano, decided to leave on its own while the monsoon winds were favorable. The other ship later tried to sail back across the Pacific to Panama, but was forced back and eventually was wrecked.

Final Leg of Magellan's Journey

With new sails and now only 47 Europeans, 13 East Indian natives and two birds of paradise (a gift from a sultan to the king of Spain), the last ship from the original five started home under the command of Juan Sebastián del Cano. The only problem is the tradition route home — via Malaysia, India, and east and west African coasts — was supplied by Portugese outposts. Magellan's ships were Spanish and the had to go out of their way to avoid Portugese ports and ships.

To avoid trouble Captain del Cano's ship went straight across the Indian Ocean, south of Madagascar and then swung wide around the Cape of Good Hope. With a lot of hungry and sick men aboard finally they pulled in for provisions at the Cape Verde Islands off the West African coast. This was a Portuguese outpost and foolishly they tried to trade cloves for food, but ended up having to make a dash for it because Portugal was supposed to have a monopoly on the trade of cloves. Thirteen crew members were left behind.

Magellan’s Ship Returns Home

Finally two months after leaving the Cape Verde Islands, seven months after the Spice Islands, and three years after leaving Spain, del Cano's ship arrived back in Spain. Of the original 3000 men that set sail only 18 returned (although the thirteen in the Cape Verde islands also made it back). The returnees were "emaciated skeletons in rags" by the time they returned. The day after their arrival home, fulfilling a vow, they walked barefoot, wearing only their shirts and carrying a candle each, a mile from the port to the shrine of Santa María de l'Antigua at the Seville Cathedral.

Of the five ships that started out only one returned to Spain after a three year voyage that covered perhaps 56,325 kilometers (35,000 miles). Since Magellan was killed in the Philippines it inaccurate to say that he circumnavigated the globe, although he got his ships through the most difficult part.

People were amazed that a ship actually sailed around the world, and the businessmen who paid for the expedition even turned a small profit after all the cloves were sold. But the men who took part in the voyage were not rewarded. Del Cano didn't receive much money or notoriety. Magellan's widow and only son both died during the voyage and his remaining heir collected no reward "not even the salary due him." The Philippines eventually became a Spanish colony serviced by ship that ran between Acapulco Mexico and Manila, but Magellan was not glorified in either Spain or Portugal.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Source: Most information in this article is from a National Geographic article by Alan Villiers, June 1976 and the book "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin. Also, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2025