Home | Category: Shark Species

OPEN OCEAN SHARKS

Pelagic (open water) inhabit tropical and temperate waters. Many are migratory and constantly on the move, relying on lift from their pectoral fins and buoyancy from the low density oils in their large livers to stop them from sinking. A total of 53 shark species are categorized as pelagic. This is far less than the hundreds inhabiting shallow coastal regions. Many are abundant and found across very wide expanses of the world’s oceans. [Source: World Wide Fund]

Open water sharks y have streamlined bodies that allow them to move through the water quickly. Blue sharks and thresher sharks are the most common sharks in the Pacific. Silky sharks are common in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. These and other oceanic shark have been overfished, either caught accidentally on long lines or caught deliberately for their fins.

Pelagic sharks feed mostly on squid and fish. They are the top predators in their range, and have few natural predators when fully grown. They also occasionally eat other sharks and some hunt turtles, seals and penguins. The three species of large plankton eating filter feeders --- whale sharks, basking sharks and megamouth shark — are considered open water sharks.

Related Articles: COASTAL SHARKS: BLACKTIP, SAND TIGER, AND DUSKY SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK SEX: REPRODUCTION, DOUBLE PENISES, HYBRIDS AND VIRGIN BIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING TECHNIQUES AND FRENZIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

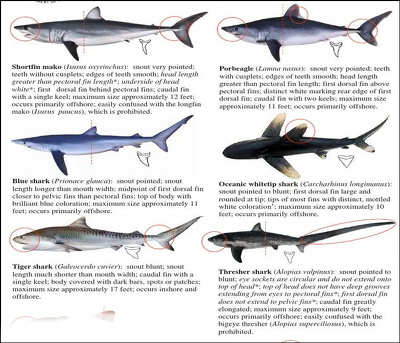

Silky Sharks, Hammerheads, Makos and Thresher Sharks

Silky sharks are among the most numerous pelagic shark. Highly mobile and migratory, they can be found around the world in tropical waters and are most commonly found over the edge of the continental shelf down to 50 meters (164 ft). The silky shark has a slender, streamlined body and typically reaches lengths of aound 2.5 meters (8 feet 2 inches). It can be distinguished from other large requiem sharks by its relatively small first dorsal fin with a curving rear margin, its tiny second dorsal fin with a long free rear tip, and its long, sickle-shaped pectoral fins. It is a deep, metallic bronze-gray above and white below.

Thresher sharks have a uniquely-shaped upper lobe on their tail that makes them unique and interesting-looking. Found in temperate and tropical oceans worldwide, they sharks use their enlarged caudal fin to herd schools of fish into tightly packed balls so they are easy attack. Threshers also use their tails for defense. Fishermen stand well clear of threshers when they are brought on board a boat. One man who got too close was decapitated with one swipe of the tail.

Hammerhead sharks are strong swimmers found mainly in the open ocean. They have distinctive heads with eyes at the end of winglike flaps. Although hammerhead usually average about 3.7 meters (12 feet) in length divers have spotted ones up to six meters (20 feet) long. Unlike other sharks they have small jaws. Those of most adults are only 30 centimeters wide. Their meat is considered too mealy and too pink for consumers. Some species migrate north to cooler waters in the summer.

Mako sharks are very fast, active and potentially dangerous sharks. They are mainly open sea predators and favorites among sport fishermen. They fight hard, leap high out of the water agaiin and again when hooked and their meat is tasty. They have large, unserrrated, dagger-like teeth, ideal for gripping slippery prey such as mackerel, tuna, bonito or squid. When attacking they make a quick lunge.

See Separate Articles: SILKY SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com; THRESHER SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING ioa.factsanddetails.com; HAMMERHEAD SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, HEADS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com; HAMMERHEAD SHARK SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com; MAKO SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING AND SHORTFIN MAKO SPEED ioa.factsanddetails.com; MAKO SHARKS AND HUMANS: FISHING, ATTACKS AND SUSTAINABILITY ioa.factsanddetails.com;

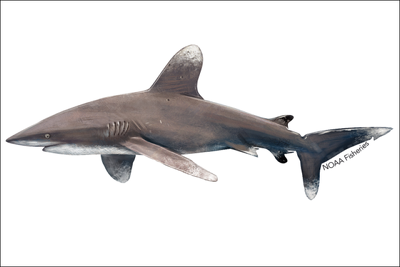

Oceanic Whitetip Sharks

Oceanic whitetip sharks (Scientific name: Carcharhinus longimanus) are large oceanic predators. They were often among the first scavengers to show up at sinking ships and downed planes during World War II. They are regarded as critically endangered in many areas. They are often snagged by longlines. Their long pectoral find are prized in shark fin soup.

Oceanic whitetip sharks reach lengths up to 3.3 meters (11 feet). They are large, pelagic (open ocean) sharks found in tropical and subtropical oceans throughout the world. Around the U.S. they are seen around New England, the Mid-Atlantic, Pacific Islands, the Southeast and West Coast They live offshore in deep water, and spend most of their time in the upper part of the water column near the surface. Oceanic whitetip sharks are long-lived, late maturing, and have low to moderate productivity.[Source: NOAA]

Oceanic whitetip sharks are generally found offshore in the open ocean, on the outer continental shelf, or around oceanic islands in deep water areas. Although they can make deep dives and have been recorded up to 1,082 meters (3,549 feet) deep, they typically live in the upper part of the water column, from the surface to at least 200 meters (656 feet deep). Oceanic whitetip sharks have a strong preference for the surface mixed layer in warm waters above 20°C, and are therefore considered a surface-dwelling shark.

Oceanic whitetip shark numbers declined by 75 percent between 1995 and 2020. Some sources list them as critically endangered, possibly facing extinction. The main threats to oceanic whitetip sharks is bycatch in commercial fisheries combined with demand for its fins. They are frequently caught in pelagic longline, purse seine, and gillnet fisheries worldwide and their fins are highly valued in the international trade for shark products. As a result, their populations have declined throughout its global range. In 2018, NOAA Fisheries listed the species as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. [Sources: Mónica Serrano and Sean McNaughton, National Geographic, July 15, 2021, NOAA]

Oceanic Whitetip Shark Characteristics, Behavior, Diet and Reproduction

Oceanic whitetip sharks are large-bodied sharks with a stocky build, and have a distinctive pattern of mottled white markings on the tips of their dorsal, pectoral, and tail fins. These markings are why they are called “whitetip” sharks. Their dorsal fins are rounded and their pectoral fins are long and paddle-like. The color of their bodies varies depending on where they live. They are generally-grayish bronze to brown, while their undersides are whitish with some individuals having a yellow tinge.[Source: NOAA]

The oceanic whitetip shark are considered a top predator, eating at the top of the food chain. They are opportunistic, feeding primarily on bony fish and cephalopods, such as squid. However, they also reportedly feed on large pelagic sportfish (such as, tuna, marlin), sea birds, other sharks and rays, marine mammals, and even garbage.

Oceanic whitetip sharks are estimated to live up to 25 years, although it is thought that individuals may live to be much older (up to 36 years). Female oceanic whitetip sharks reach maturity between 6 and nine years of age (depending on geographic location) and give birth to live young after a very lengthy gestation period of 10 to 12 months. The reproductive cycle is thought to be biennial, with sharks giving birth on alternate years to litters ranging from 1 to 14 pups (average of 6). There is also a likely correlation between female size and number of pups per litter, with larger sharks producing more offspring.[Source: NOAA]

Oceanic Whitetip Shark Attacks

Oceanic whitetip sharks are considered the fourth most dangerous sharks for people. They swarm in the waters off Cat Island in the Bahamas and have killed swimmers in the Red Sea. Most of the shark attack deaths after the sinking of the Indianapolis in World War II — and event immortalized in Quint’s soliloquy in “Jaws” — were attributed to Oceanic whitetips. Oceanic whitetip sharks (Carcharhinus longimanus) have accounted for 12 non-fatal attacks and 3 fatal attacks for of total of 15 attacks. [Source: International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, 2023]

In December 2010, The Guardian reported: “A 70-year-old German tourist died after being mauled by a shark off the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh — the latest in a series of shark attacks in the Red Sea over the past five days.

The attack was thought to have been carried out by a oceanic white tip shark. Attacks by oceanic white tip sharks are extremely rare and shark attacks of any kind are very unusual in the Red Sea. According to security officials quoted by the Associated Press, the German woman's arm was severed in the attack and she died within minutes. The week before three Russians and a Ukrainian were badly injured. The Egyptian authorities had said they were confident that the capture and killing of two sharks had eliminated the threat to swimmers. A 48-hour ban on entering the water had been lifted yesterday but all watersports, except for diving sites, have been closed again following attack on the German. [Source: Harriet Sherwood, The Guardian, December 5 2010]

In 2019 a French tourist was severely injured in a rare shark attack off the coast of Tahiti. Newsweek reported: The 35-year-old woman was swimming in the waters off Moorea island on a whale-watching trip on Monday, according to Radio New Zealand, when she was attacked by an oceanic whitetip shark that ripped into her chest and arms. The woman was airlifted to a hospital in Tahiti and was reported to have lost both hands and a lot of blood, according to firefighter Jean-Jacques Riveta. "Luckily for her, there were two nurses on the scene who could deliver first aid," he told AFP. [Source: Soo Kim, Newsweek, October 22, 2019]

See the Indianapolis Story Under HISTORY OF HUMANS AND SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK ATTACKS IN THE RED SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com and Attacks in Tahiti and French Polynesia Under SHARK ATTACKS IN THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com

Threats to Oceanic Whitetip Sharks

The primary threat to oceanic whitetip shark is incidental bycatch in commercial fisheries, including longlines, purse seines, and gillnets (among other gear types) Because of their preferred distribution in warm, tropical waters, and their tendency to remain at the surface, oceanic whitetip sharks have high encounter and mortality rates in fisheries throughout their range. Their large, distinct fins are also highly valued in the international shark fin trade.[Source: NOAA]

Information on the global population size of the oceanic whitetip is lacking. However, several lines of evidence suggest that the once common and abundant shark has experienced declines of potentially significant magnitude due to heavy fishing pressure. For example, the oceanic whitetip has declined by approximately 80 to 95 percent across the Pacific Ocean since the mid-1990s. Substantial abundance declines have also been estimated for the Atlantic Ocean, including an 88 percent decline in the Gulf of Mexico due to commercial fishing. Given their life history traits, particularly their late age of maturity and low reproductive output, oceanic whitetip sharks are inherently vulnerable to depletions, with low likelihood of recovery. Additional research is needed to better understand the population structure and global abundance of the oceanic whitetip shark.

Protected Status: Endangered Species Act (ESA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife): Threatened throughout Its range. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but may become so unless trade is closely controlled: Throughout Its range. Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) Annex III

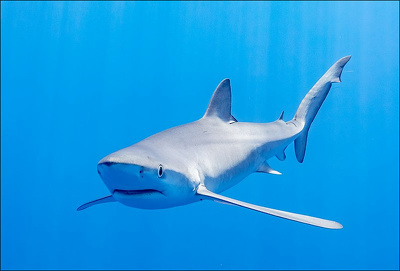

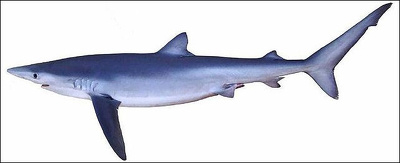

Blue Sharks

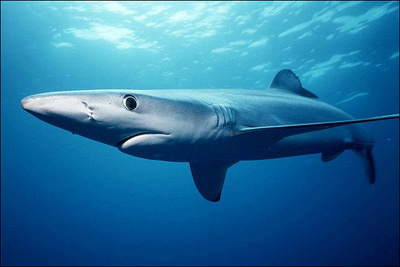

Blue sharks (Scientific name: Prionace glauca) are found mostly in tropical and temperate waters throughout the world. Regarded as one of the widest ranging vertebrate in the world, they are common in the open ocean everywhere and migrate seasonably between cooler and ware waters. Divers around reefs rarely come in contact with them.

Blue sharks are large. They reach a length of four meters (13 feet) and weigh up to 250 kilograms (550 pounds). They sharks are regarded as non aggressive but potentially dangerous. Blue sharks have accounted for nine non-fatal unprovoked attacks and 4 fatal attacks for of total of 13 attacks according to the International Shark Attack Files (ISAF). Due to the fact they spend most of their time in the open ocean, blue sharks are rarely encountered by divers and swimmers. As of 2012, the ISAF recorded nearly two dozen additional, provoked attacks.

According to the International Game Fish Association the largest blue shark ever caught weighed 240 kilograms (528 pounds) and was taken in. Montauk, New York in 2001. Blue sharks have an average lifespan of 15 to 16 years in the wild. Their life expectancy drops off to average of eight years when in captivity, perhaps because they can not engage in their usual pelagic and migratory behaviors. [Source: Florida Museum of Natural History, 2023]

Blue sharks are apex-level predators. They feed on many species of fish that help to regulate prey populations. Outside of humans, who pursue them for fins, for the lucrative shark fin trade, blue sharks have few predators. They are occasionally preyed upon by orcas and larger sharks such as shortfin makos and great whites. There have been reports of juveniles being hunted and killed by California sea lions. Pilotfish have symbiosis relationship with blue sharks. They clean the shark's teeth and gills and remove parasites from the shark's skin. In return, pilotfish gain protection from predators and a ready source of food. [Source: Alexandra Axtell and Joseph Boucree, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Blue sharks prey on up to 16 species of fish — including small schooling fishes, such as snake mackerel, castor oil fish and long-snouted lancetfish — and 24 species of cephalopods — mainly non-active, gelatinous, mesopelagic-bathypelagic species such as bathyscaphoid squids blanket octopus and pelagic octopus. During their reproductive migration cycles off of the coast of Brazil, blue sharks have been observed consuming seabirds, including great shearwaters. [Source: Alexandra Axtell and Joseph Boucree, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Blue sharks often follow trawlers and feed on trapped fish and have been observed gathering in number to attack a whale or dolphin carcass. Typically, when hunting for fish they circle their prey before attacking from below. Like all sharks, blue sharks have highly developed senses of sight, smell and touch. The lateral line — a sensory organ running down the length of their body that detects pressure waves from movements in the water — allowing the sharks to perceive vibrations from the movements of prey. Their Ampullae of Lorenzini electroreceptors on the underside of the snouts detect electrical fields generated by the muscle contractions of prey items.

Blue Shark Habitats and Where They Are Found

Blue sharks are one of the most wide ranging and abundant shark species. They are distributed throughout all major oceans (except the Arctic), as well as the Mediterranean. Found as far north as Alaska and as far south as Chile, but rarely venturing near shore, they are typically found in temperate and tropical pelagic (open ocean) waters at depths of zero to 350 meters (1148.29 feet). This is probably because blues are abundant: They They prefer water temperatures ranging between 12 and 20°C (53 and 68̊F) . While they are mainly found in open-ocean waters, they may sometimes be found closer to shore in upper layers of the ocean, near the edge of continental shelves.

Blue sharks are regarded as great oceanic travelers, often traversing distances of 3,000 kilometers in their search of food and mates. They migrate in a clockwise pattern around the Atlantic basin from breeding ground to feeding grounds, saving energy by riding the currents of the North Atlantic They follow the Gulf Stream from the Caribbean up east coast of the U.S. east to Europe, south to Africa, and back to the Caribbean.

Blue sharks share territory with shortfin mako sharks. Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: The two species are kind of like lions and hyenas, coexisting in the same areas as they pursue different feeding strategies. Shortfin makos chase down speedy prey such as bluefish and tuna. Blue sharks, on the other hand, are relatively laconic and focus on slower prey, like squid. Catching them is like, in one fisherman’s words, “reeling in a barn door,” and their meat is not nearly as good to eat as a mako’s. So you can guess which one is the lion in the analogy and which is the hyena. Everyone wants to bag the lion. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, August 2017]

Blue Shark Global Migrations

Jasmin Graham wrote in The Conversation: Blue sharks are among the widest-ranging shark species in the oceans. We know this partly because from 1962 to 2013, 117,962 blue sharks were tagged as part of the ongoing Cooperative Shark Tagging Program. This partnership between the commercial fishing industry, the U.S. government, recreational fishermen and academic research scientists is the longest-running tagging program in the world. Since its launch in 1962, participants have tagged hundreds of thousands of sharks representing 35 different species. More than half (51 percent) of the animals tagged were blue sharks – a total of 117,962 individual sharks. [Source: Jasmin Graham, Ph.D. Candidate in Marine Science, Florida State University, The Conversation, March 24, 2020]

Tagging data confirm that blue sharks migrate incredibly long distances, with some even crossing the equator from the North Atlantic to the South Atlantic. All of this movement allows them to mix and mingle with individuals throughout their range. This tells scientists that all blue sharks in the Atlantic Ocean are part of one mating pool, and can be considered one big population, rather than smaller separate groups. [Source: Jasmin Graham, Ph.D. Candidate in Marine Science, Florida State University, The Conversation, March 24, 2020]

Each tag attached to a shark carries an identification number and contact information, so that recaptures can be reported and matched to data collected during the initial tagging. The data show that these sharks really move. About 7 percent of the tagged blue sharks (8,213) were recaptured later, sometimes after more than a decade. One shark was recaptured nearly 16 years after it was first tagged. Scientists estimated that this shark was between 8 and 11 years old at the time it was tagged, based on its size. That original age estimate would have made the shark 24 to 27 years old when it was recaptured, which falls within the current estimated range of maximum age for the species.

The sharks were caught in all seasons throughout their range, in tropical waters warmer than 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius) and temperate waters, which range from 50°-68°F (10°-20°C). In more tropical climates, blue sharks occupy waters as deep as 1,150 feet (350 meters), which are cooler than water near the surface. Their ability to inhabit a wide range of depths enables them to move around as seasons and water temperatures change. One traveled a record-breaking 3,997 nautical miles (7,402 kilometers) from waters off Long Island, New York, where it was first tagged, to the south Atlantic where it was recaptured – a distance longer than the Great Wall of China.

Blue Shark Characteristics and Behavior

Blue shark are cold blooded (ectothermic, use heat from the environment and adapt their behavior to regulate body temperature) and heterothermic (have a body temperature that fluctuates with the surrounding environment). They reach lengths of four meters (13 feet), with their average length being 3.35 meters (11 feet). They reach weights of 240 kilograms (530 pounds). Females are larger than males.[Source: Alexandra Axtell and Joseph Boucree, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The striking blue color of blue sharks makes them one of the most distinctive species in the requiem-whaler-shark (Carcharhinidae) family. Their back side (dorsum) is a deep indigo sahd and their flanks are vibrant blue. One adaption that blue sharks have that helps them in the pelagic environment is countershading — having lighter coloration on their under (ventral) side, which helps to camouflage the sharks against the background of lighter-colored water when viewed from below and having darker shades of blue and silver on their back (dorsal) side allows them to blend in with the depths below when viewed from above.

Blue sharks have long, winglike pectoral fins and cruise at relatively high speeds for long periods of time. According to Animal Diversity Web: The body is streamlined and thin, with an elongated heterocercal caudal (tail) fin, making it one of the fastest sharks in the ocean. The second dorsal fin is approximately half the size of the first, and the pectoral fins are proportionately longer than in most other shark species. The eyes are large, and the mouth is lined with several rows of triangular, serrated teeth; each tooth is usually replaced every eight to 15 days.

Blue sharks are diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds) and solitary. As a free-ranging pelagic fish, they maintain neither permanent home ranges nor territories. Blue sharks sometimes form gender-specific schools of similar-sized conspecifics. It is currently unknown what purpose these schools serve. Blue sharks communicate with vision and sense using vision, touch, sound, vibrations, electric signals and chemicals that can be detected by smelling.

Blue Shark Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Blue sharks are viviparous (they give birth to live young that developed in the body of the mother) and iteroparous (offspring are produced in groups such as litters). They employ sperm-storing (producing young from sperm that has been stored, allowing it be used for fertilization at some time after mating) and use delayed fertilization in which there is a period of time between copulation and actual use of sperm to fertilize eggs; due to sperm storage and/or delayed ovulation. [Source: Alexandra Axtell and Joseph Boucree, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Blue sharks engage in seasonal breeding but it is unknown whether female blue sharks breed annually, or less frequently. The gestation period ranges from nine to 12 months. In the northern Pacific, most births occur from December to April. The number of offspring ranges from 25 to 130. Usually 25 to 50 pups are born. Females reach sexual maturity at five to six years at around 2,2 meters (7.2 feet). Females Males reach sexual maturity at five to six years at around 1.9 meters (6.1 feet)

Blue sharks are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They congregate together on continental shelves during the summer. During mating, the male bites into the female between her first and second dorsal fins. It is not surprising then that the skin of the female in this part of her body is three times thicker than the male's. Fertilization takes place after the male inserts one of the claspers into the female's urogenital opening. After mating, individuals so their separate ways.

Parental care and pre-birth provisioning and protecting is provided by females. After insemination males have no involvement. Once pregnant, females migrate north to birthing and pupping grounds in the sub-Arctic boundary. on average. Embryos develop inside the female's uterus, nourished by a placenta-like yolk sac. Females give birth to fully-developed, live young. Pups are between 35 to 50 centimeters (1.1 to 1.6 feet) in length at birth, averaging 39 centimeters (1.3 feet) at birth. After birth, shark pups are independent and have no further contact with their mother. Blue sharks have one of the fastest growth rates of all sharks, growing up to 30 centimeters (0ne foot) a year until maturity. Juveniles usually stay in pupping areas of the sub-Arctic boundary (42°N North Pacific Ocean) until they reach maturity at five years of age.

Humans, Blue Sharks and Conservation

Although mainly caught indirectly as bycatch on long lines and in gill nets, blue sharks, like many shark species, are valued commercially for their fins, squalene (liver oil), skin, cartilage, and their teeth and jaws. Their meat is less valued because of its high ammonia content. In the 2000s, 6 million blue sharks were caught by fishing vessels, mainly for their fins. Blue sharks are considered by pests by some commercial fishermen (particularly those of fishing for mackerel, pilchard, and salmon) as they prey on the species the fishermen are fishing for and ruin nets by becoming entangled in them.

Jasmin Graham wrote: Unlike some other sharks, blues are not a prized commercial species, likely because most people think they taste disgusting. That makes fishermen willing to tag and release them instead of harvesting them. But blue sharks are often caught unintentionally as bycatch along with targeted fish. They are classified as near threatened, and there is evidence that their population is decreasing.[Source: Jasmin Graham, Ph.D. Candidate in Marine Science, Florida State University, The Conversation, March 24, 2020]

According to National Geographic blue shark population decreased 29 percent between 1975 and 2020. They sharks are the top species in the fin trade. They’re protected by only a few national catch limits. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists blue shark as “ Near Threatened”; They have no special status according to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). [Source: Mónica Serrano and Sean McNaughton, National Geographic, July 15, 2021]

International conservation projects have been implemented to decrease the harvest of blue sharks and other pelagic sharks. In 1991, the Australian Government introduced legislation that banned longline fishing fleets from taking shark fins without their attendant carcasses. In 1995 Canada established catch limits for blue sharks of 250,000 kilograms, and implemented limitations on finning and gear use. Licensing and commercial quota limits have been established and finning has been banned within the US Exclusive Economic Zone.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023