SHARK FEEDING

feeding sharks in the Bahamas Many sharks ambush or surprise their prey or catch it in a high speed pursuit in open water. Some sharks on the hunt circle their victims in smaller and smaller circles and first bump the prey then bite it. Others simply search a given area for slow-moving prey that is easy to catch. "A shark is an opportunist," one scientist said. "It frequently hunts the weak, the old, the stupid, and the crippled." As wolves do with a herd of caribou, sharks strengthen the breeding stock of a species by removing the genetic weaklings.[Source: Nathaniel Kenney, National Geographic, February 1968]

According to NOAA Fisheries, part of the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, sharks “can go up to approximately six weeks without feeding” before entering an “eating phase”. Samuel Gruber of the Bimini shark lab in the Bahamas told New Scientist sharks are highly social and can hunt cooperatively. During the great sardine run off of South Africa, a massive fish migration in which cooperative feeding is observed among several shark species, dolphins, sea lions and sea birds.

Hunters such as sharks and tuna rely on speed to capture prey. They keep their bodies significantly warmer than the water they swim in. Sharks that feed on prey larger than themselves have triangular teeth, suited for cutting and slashing. Sharks that snatch fish from the sea have many smaller teeth ideal for grabbing and gripping. Those that purse hard prey have closely set knobs.

The white-spotted bamboo shark — a species native to the Indo-Pacific region and often found in aquariums because it lays eggs in captivity and accepts feeding — have teeth that extend forward when ripping into the flesh of a fish but bend inward when they encounter something hard like the shell of a crab, turning the teeth into flat dental plates suited for such hard-shelled prey. The teeth fold down or fold up in milliseconds in response to hard or stiff prey or prey parts.

Related Articles: SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK SEX: REPRODUCTION, DOUBLE PENISES, HYBRIDS AND VIRGIN BIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF SHARKS: EARLIEST ONES. DINOSAUR-ERA ONES AND MEGALODON ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Shark Prey

According to NOAA, Sharks, the agency says, “will eat anything”. Objects found in sharks’ stomachs have included “tires, license plates, a fur coat, a chicken coop and even a full suit of armor. But generally, sharks are omnivorous, which means usually they just eat meat and plants. If there is not an abundant supply of meat in the area, they will resort to eating sea vegetation.”

According to NOAA, Sharks, the agency says, “will eat anything”. Objects found in sharks’ stomachs have included “tires, license plates, a fur coat, a chicken coop and even a full suit of armor. But generally, sharks are omnivorous, which means usually they just eat meat and plants. If there is not an abundant supply of meat in the area, they will resort to eating sea vegetation.”

Many sharks feed on flatfish and rays. They use sharp, small teeth for gripping and kill and break their prey into small pieces by vigorously shaking their heads. Dusk and dawn are favorite feeding times. Sharks are often attracted by fish that appear to be struggling, splashing, weakened or stressed.

Many smaller sharks eat crabs, mollusks and small fish. Crabs, brittle starts and sea urchins are easy to catch but difficult to break apart. Sharks that feed these creatures use their teeth to crush up the shells, which they spit out. This in an adaption that was developed more than 400 million years ago when ancient sharks fed on armored fish.

Shark Feeding Frenzy

A feeding frenzy ensues when a group of sharks became very aggressive and appear to go berserk in the pursuit of bloody fish or some other prey. Feeding frenzies have been likened to mob behavior in humans, with the overload of stimulation erasing inhibition."

In the midst of a real feeding frenzy sharks have been observed biting their own kind but usually this does not happen. Explaining why sharks in the middle of a feeding frenzy show no aggression towards each other shark researcher Donald Nelson of California State University said, "the feeding scramble is like a football fumble. Everyone goes for the ball, not each other." [Source: Eugenie Clark, National Geographic August 1981]

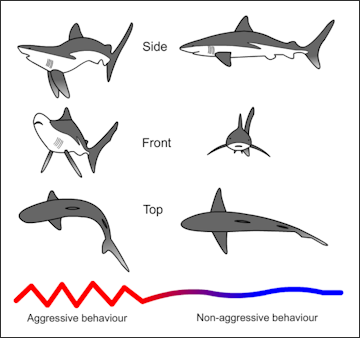

Shark threat display Shark feeding frenzies often thought to be triggered by blood in water are more likely set off by the head shaking vibrations of the first shark to feed. Sharks respond to low frequency sound and pressure waves. When the sounds of wounded fish and thrashing swimmers have been played over a loud speaks sharks have been observed ceasing their activity and heading straight for the sound.

In 2023, The Guardian reported: Thinking he had spotted a “tuna boil”, and thereby found his own prey, a Louisiana fisherman soon realised he had instead stumbled across a huge group of sharks engaged in a feeding frenzy. “Never seen anything like it,” Dillon May told Storyful, to whom he provided video of the remarkable scene. [Source: Martin Pengelly in New York, The Guardian, March 2, 2023]

“The sharks, May said, were feeding on a large pod of menhaden, a small fish, common off the eastern US, that is preyed upon by other fish and mammals including humpback whales, and which the Nature Conservancy calls “the most important fish in the sea”. May said he and his girlfriend, Kaitlyn Dix, were about 15 miles off Venice, Louisiana, and on a friend’s boat, which took on water as the sharks thrashed around it. “The sharks had found the pod and pushed them up against the boat to feast on them,” he said.

Grey Reef Shark Feeding Frenzy

Describing an encounter with grey reef sharks lured by a bucket of dead fish, Peter Benchley wrote in National Geographic, "Before we could clear out masks grey reef sharks were on us — quick, curious, unafraid darting around us like a pack of wild dogs."

After the bucket was open, "The ocean exploded. Sharks swarmed like enraged bees — dozens of them, scores perhaps’snapping and biting and twisting and tearing, their bodies torqued in impossible contortions, their jaws extended, their eyes partly covered by nictitating membranes that gave them the look of murderous cats. They were a tightly wrapped ball of frenzy.”

"The bucket rose in the water and spun, throwing off a cloud of blood. Sharks charged it, and disappeared in a flurry of bodies. A shark grabbed one of David's fins and worked it, as a dog worrks a bone. Another shark opened its mouth, turned towards me and lunged, trying to force its way between David and me. I struck it with the heel of my hand, and it sped away...And then it was over. In an instant they were gone."

Sharks Seen Hunting and Killing a Whale for the First Time

In 2015 a group of dusky sharks was observed attacking and killing a four- meter-long humpback whale calf. It the first time that sharks had been recorded hunting and killing. New Scientist reported: “Spotted off the eastern coast of South Africa, in the Pondoland Marine Protected Area, a humpback whale calf some 4 meters long endured a harrowing ordeal, beset by a group of dusky sharks, each 2 to 3 meters long. These beasts tend to dine on fish found in coastal and pelagic waters and occasionally marine mammals such as dolphins and porpoises. [Source: Rachel David, New Scientist, December 16, 2015]

“For a couple of hours the humpback whale calf swam in circles, pursued by between 10 and 20 sharks, says cinematographer Morne Hardenberg, who witnessed the encounter. “The calf was bitten many times, thrashed vigorously at the surface when attacked, and attempted to swim away. “We stayed with it for a while and it was doing the same manoeuvring, with the sharks following it, and then it just disappeared,” he says. The calf probably drowned from exhaustion, its carcass never recovered — it’s not clear if the sharks ate it in the end.

“This is the first time any shark has been directly documented attacking a whale. Other species, such as tiger sharks, are known to be partial to whale meat, but they get it by scavenging. Matt Dicken from the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board in South Africa, who with his colleagues published a report of the incident, believes that such attacks might be more common than we think. “It’s still probably quite rare, but they are happening,” he says.

“Dicken doesn’t think that the sharks were actually hunting together. They were probably just aggregating around the calf attacking it opportunistically, he says. The East African humpback whale population is growing, so we might see more shark attacks in future, Dicken’s paper published in Marine and Freshwater Research, suggests. The massive megalodon shark, which has been extinct for 2.6 million years, is thought to have preyed regularly on baleen whales, says Samuel Gruber of the Bimini shark lab in the Bahamas. The evidence for this comes from megalodon tooth marks found on whale bones. Still, sharks are unlikely to pose a regular danger to healthy whale calves, Gruber says, suggesting this calf might have been injured. Or it may have been abandoned by its mother, says Dicken, and so was more vulnerable.

Sharks Take Turns Hunting by Species

Six species of sharks were observed off the coast of Florida taking turns searching for food in 2021. The discovery was the first of its kind and quite unexpected, according to the study in The Royal Society that announced the finding. . “This is a relatively rare way of sharing resources in nature, but it could be more common than we think in understudied marine ecosystems,” said Karissa Lear, a lead researcher of the study, from Murdoch University’s Harry Butler Institute in Australia.

Chacour Koop wrote in the Idaho Statesman: “Lear and other researchers strapped FitBit-like devices on six shark species near Tampa Bay and analyzed 3,766 hours of data from 172 of them. “We found bull sharks were most active in early morning hours, tiger sharks during midday, sandbar sharks during the afternoon, blacktip sharks during evening hours and both scalloped and great hammerhead sharks during nighttime hours, the only two species with substantial overlap in timing of peak activity,” Lear said. [Source: Chacour Koop, Idaho Statesman, July 9, 2021]

“So, are these sharks just really well-mannered? Not exactly. The sharks are practicing something called “niche partitioning,” which allows species competing for the same resources to coexist, researchers say. “Niche partitioning can take several forms in nature, with species either specializing in different food, foraging or hunting in different areas, or rotating the time they hunt or forage.

“The sharks in this study practiced the latter form, scientifically called “temporal partitioning.” Researchers say this is the first time marine predators have been observed partitioning resources by searching for food at different times of the day. “This both reduced the competition for food and, for some species, reduces the chances of being preyed upon by larger species,” Adrian Gleiss, another lead researcher, said in a news release. The larger and more dominant species — the tiger, bull and great hammerhead sharks — hunted at times of the day that perhaps suited them best, researchers say. For example, researchers say hammerhead sharks have “superior binocular vision,” putting them at an advantage at night, while tiger sharks are believed to use silhouettes of prey to hunt, a tactic that requires more light. Meanwhile, smaller species like blacktip sharks may change their feeding time to avoid run-ins with larger sharks.

100-Shark Whale Carcass Feeding Frenzy

In May 2022 up to 100 sharks were filmed feasting on a whale carcass in a "feeding frenzy" off the coast of Australia in . The drone footage was captured by John Cloke and posted to his Instagram account, jindys_travels, which he shares with partner Indy Crimmins. According to Newsweek: It shows a 49-foot whale carcass floating in the water. Sharks surround the carcass, and as the camera moves further out, more sharks can be seen swimming toward it to feed. [Source: Robyn White, Newsweek May 18, 2022]

Cloke said didn’t know for sure how many sharks there were. "We could count at least 60 when stopping the footage but [we're] not 100 percent sure." Cloke told ABC Australia that at one point there may have been up to 100 sharks around it. "It was pretty full on," he told the news outlet.

It is not clear what species of sharks were feasting on the carcass, however, multiple species, including great whites, live in Western Australia waters throughout the year. Shortly after the footage was captured, a humpback whale carcass washed up on Normans Beach. The washed up carcass was spotted by a beachgoer who reported it to the wildlife officers, Perth Now reported. Wildlife officials confirmed that it had been eaten by sharks.

As a result, Normans Beach was closed off to ensure the safety of the public, It is not uncommon for sharks to feast on whale carcasses. While the species are infamous for being apex predators, dead whales present an opportunity for them to scavenge an easy meal rich in energy. Sharks are unlikely to attack fully grown, live whales on a regular basis because of their size. They may occasionally attack calves, however, and smaller mammals. When a whale dies the body will often expand with gas, causing it to float to the top of the surface. Ocean currents will often eventually cause it to become washed ashore.

Sharks Impaled by Swordfish

The sharks don’t always win their battles for food and survival. A number of sharks impaled by swordfish have washed up on Mediterranean shores, backing up old fishermen’s tales about battles between the two marine predators. Joshua Sokol wrote in the New York Times: The first victim washed up in September 2016. The police in Valencia, Spain, saw a blue shark dying in the surf along a tiny stretch of beach. They lugged the 8-foot corpse to the yard behind the police station. Then they called Jaime Penadés-Suay, who soon suspected foul play. The shark had what looked like a bit of wood embedded in her head. He pulled. Out slid a broken fragment from a swordfish sword that had lanced straight through her brain. “I thought it was crazy,” said Penadés-Suay, a graduate student at the University of Valencia and a founder of LAMNA, a Spanish consortium that studies sharks. “I was never sure if this was some kind of joke.” [Source: Joshua Sokol, New York Times, October 28, 2020]

“But since then at least six more sharks have washed up on Mediterranean coasts, each impaled with the same murder weapon, and almost always in the head. In the latest example, an adult 15-foot thresher shark — itself equipped with a whiplike tail capable of stunning blows — washed up in Libya. Inside was a foot of swordfish sword that had broken off near its heart. Taken together these cases offer what may be preliminary scientific evidence of high-speed, high-stakes underwater duels that had previously been confined to fisherman’s tales.

Historically, whalers, fishermen and scholars saw swordfish as stab-happy gladiators. But modern scientists were skeptical. Sure, swordfish sometimes impale boats, whales, submarines and sea turtles. But perhaps these swordfish had aimed for smaller prey and rammed something else by mistake. Or maybe not. When sharks die, their bodies typically sink to the bottom of the sea. So a published record of half a dozen stranded sharks with suspiciously precise wounds could indicate that these encounters are common — and that a swordfish sword is sometimes exactly what it sounds like. “Now at least we have evidence that they might use it really as a weapon, intentionally,” said Patrick Jambura, a graduate student at the University of Vienna.

Jambura led a study of the recent dead thresher shark, which turned up in April. Sara Al Mabruk at Omar Al-Mukhtar University in Libya had spotted a video posted by local citizen scientists. In the video, a man approaches a shark on the beach, then pulls a sword from its back like a bizarre twist on Arthurian legend. “I was like, ‘Oh come on Sara, we have to do something about this. That’s just incredible,’” Jambura said. It’s also puzzling, their team reported in October 2020 in the journal Ichthyological Research. Fishermen often catch swordfish with mangled swords, so breaking one isn’t fatal, but they do help their owners swim faster and feed. And they don’t seem to grow back, at least not for adults. So why do some swordfish risk losing them?

Most victims of swordfish stabbings in the Mediterranean have been blue or mako sharks. Both of those species prey on young swordfish, suggesting one explanation: Maybe juvenile swordfish had felt like their lives were threatened and fought back. But this time the sword fragment looked as if it had come from an adult swordfish, which typically are not eaten by a thresher shark. Instead, they argue, the swordfish might have been taking out an ecological rival. In the overfished Mediterranean, the swordfish might have fought to ensure a larger share of the remaining scraps. Penadés-Suay doubts competition would be enough of a motive given the risks involved in taking on a big, whip-tailed shark. Instead, he thinks, the swordfish might have felt attacked and tried to protect its territory.

Either way, scientists know little about the behavior. After partnering with a seafood company, Penadés-Suay is now working to measure both 1,000 swords and the overall size of the fish that wielded them. That should help scientists extrapolate from the little crime-scene shards left in sharks to the full swordfish that did the deed. Scientists searching for these rare incidents also want to hear from the public. “Maybe a fisherman for 13 years has been catching sharks, and every year he finds this,” Penadés-Suay said. “We need everybody to be looking into this.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023