Home | Category: Humans, Sharks and Shark Attacks

NEANDERTHALS ATE SHARKS

Shark teeth found in Neanderthal cave in Portugal

Neanderthals in present-day Portugal ate sharks, dolphins, fish, mussels and seals according to a study published in March 2020 in the journal Science.. The BBC reported: Scientists found evidence for an intensive reliance on seafood at a Neanderthal site in southern Portugal. Neanderthals living between 106,000 and 86,000 years ago at the cave of Figueira Brava near Setubal were eating mussels, crab, fish — including sharks, eels and sea bream — seabirds, dolphins and seals. [Source: Paul Rincon, Science editor, BBC News website, 26 March 2020]

The research team, led by Dr João Zilhão from the University of Barcelona, Spain, found that marine food made up about 50 percent of the diet of the Figueira Brava Neanderthals. The other half came from terrestrial animals, such as deer, goats, horses, aurochs (ancient wild cattle) and tortoises.

For decades, the ability to gather food from the sea and from rivers was seen as something unique to our own species. Some of the earliest known evidence for the exploitation of marine resources by modern humans (Homo sapiens) dates to around 160,000 years ago in southern Africa. A few researchers previously proposed a theory that the brain-boosting fatty acids seafood contributed to enhanced cognitive development in early modern humans.

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Tracking Sharks trackingsharks.com, which records all global shark attacks; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Related Articles: ENDANGERED SHARKS AND COMMERCIAL FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARK PRODUCTS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARK FIN SOUP AND TRYING TO STOP CONSUMPTION OF IT ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARK TOURISM AND SWIMMING WITH SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING TECHNIQUES AND FRENZIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

“Shark Hook” Used off Israel's Coast 6,000 Years Ago

In March 2023, researchers announced they had an unearthed a large copper "shark hook" at a newly discovered village buried under a known archaeological site in Israel. Live Science reported: Archaeologists unearthed the "shark hook" during a 2018 survey along the Mediterranean coast on the outskirts of Ashkelon, a city that was built on top of an ancient seaport of the same name and dates back as far as ancient Egypt. New excavations revealed parts of a village that date back around 6,000 years to the Chalcolithic period, also known as the "Copper Age," which lasted between 4500 B.C. and 3500 B.C. in the region. [Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, March 31, 2023]

The hook is around 2.5 inches (6.5 centimeters) long and 1.6 inches (4 cm) wide, which is big enough to reel in sharks between 6.5 and 10 feet (2 and 3 meters) long, such as dusky sharks (Carcharhinus obscurus) and sandbar sharks (Carcharhinus plumbeus), or large fish such as tuna, all of which are local to the Mediterranean. However, given what marine biologists know about the deep-sea ecosystems in the region, sharks were a more likely target, according to The Times of Israel.

The discovery is a "unique find" because most other fishing hooks uncovered from this time period are smaller and made from bone, Yael Abadi-Reiss, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority who co-led the excavation, said in a statement. It's possible that this is one of the first metal variants that people created in the region, considering copper was a relatively new material at the time, she added. "The rare fishhook tells the story of the village fishermen who sailed out to sea in their boats and cast the newly invented copper fishhook into the water, hoping to add coastal sharks to the menu," Abadi-Reiss said.

80 Million-Year-Old Shark Teeth Found in a 3,000-Year-Old Jerusalem Basement

In 2021, researchers announced that they had unearthed a mysterious cache of 80-million-year-old fossilized shark teeth in a 3,000-year-old basement in Jerusalem. During a presentation at the Goldschmidt Conference, archaeologist Dr. Thomas Tuetken of the Institute of Geosciences at the University of Mainz, said that the shark teeth were found among debris and discarded material that were used to fill in the lowest level of an Iron-Age house in the village of Silwan (which later became Jerusalem). Heritage Daily reported the teeth were found with food waste and pottery shards from a period that dates just after the death of the biblical King Solomon.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 18, 2021]

more shark teeth found in Neanderthal cave in Portugal

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: “Initially, the archeologists thought that the teeth were just waste from food preparation. It was only when a reviewer prompted them to revisit the evidence that they realized that the remains came from a Late Cretaceous shark that had been extinct for at least 66 million years. Further scientific testing performed by the team revealed, said Tuetken, that “all 29 shark teeth found in the City of David were Late Cretaceous fossils — contemporary with the dinosaurs.” The strontium isotope composition of the teeth suggests an age of about 80 million years.

“The question at that point was, how did the teeth get there? Tuetken notes that they were almost certainly transported to the region, “possibly from the Negev, at least 80 kilometers away, where similar fossils” have been found. The team’s “working hypothesis is that the teeth were brought together by collectors… There are no wear marks which [had they been present] might show that they were used as tools, and no drill holes to indicate that they may have been jewelry. We know that there is a market for shark teeth even today, so it may be that there was an Iron Age trend for collecting such items.”

The 10th century BCE was a period of economic development and flourishing in Judea. Collecting is a wealthy person’s hobby: that the teeth were discovered alongside administrative bullae (the seals used to secure and authenticate ancient correspondence) further supports this theory. “We don’t have anything to confirm” that, cautioned Tuetken, “it’s too easy to put 2 and 2 together to make 5. We’ll probably never really be sure.The teeth in question have been identified as belonging to several species of extinct Squalicorax, or crow shark, a coastal predator and scavenger that grew to between 2 and 5 meters (for reference a great white shark grows to between 3-6 meters depending on its sex).

Sharks in the Ancient World

Few sharks roam the waters of the Mediterranean today, but that is not to say ancient people were not fascinated with them. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: For centuries human-eating sea monsters dominated the imagination of ancient peoples, who saw them as inherently terrifying. One of the first known accounts of a shark was a description written by Herodotus in 492 B.C., describing shipwrecked Persian sailors being attacked by “sea monsters” in the Mediterranean. Centuries later the Greek poet Leonidas of Tarentum immortalized a sponge diver named Tharsys who was bitten in two by a shark. Sharks also have been featured prominently in the literature and folk stories of groups from Hawaii to west Africa to Australia. The ancient Mayans regarded them as sacred but evil. Polynesians considered them to be guardian spirits. They have stories about royals who roped sharks and rode them like bulls. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 18, 2021]

nurse shark in a second-century BCE mosaic from a Roman house in PompeiiPhoto by Naples National Archaeological Museum

The presence of sharks in the Mediterranean is well documented in archaeology, but is also clear just from reading ancient literature. The third century BCE Greek poet Leonidas describes the death of a sponge diver at the hands of a shark and Aristotle even gives a lengthy description of the shark in his History of Animals. The Roman admiral and encyclopedia writer Pliny notes that sponge divers often had run-ins with sharks and advised that “the only safe course is to turn on the sharks and frighten them” (Natural History 9.148) Other writers like Diogenes describe sea monsters that can “swallow up both ships and their men.”

“Arguably the expert here is the second century CE Greek writer Oppian, whose influential poem the Halieutica uses the world of the sea to describe the order of the universe. As University of Nottingham classicist Emily Kneebone shows in her engaging and recently released book on the subject, Oppian describes the “terrors of the sea” — the Hammer-head, Saw-fish, Dog-fish, and solitary sharks — as outstripping their terrestrial counterparts the lion, leopard, bear and wild boar. The terrors of the sea were so considerable, Oppian writes, that the young of Dogfish would renter her “loins” when they got frightened (yes, it was apparently as painful as it sounds). The poem concludes with a whale-chase to make Melville envious: a huge sea monster from the depths — something that Kneebone describes as lying “somewhere between a shark and a whale in form” — is hunted down and killed.

Shark-Like Beasts in The Bible

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: “While it tends not to provide anatomical descriptions, the Bible has more than its fair share of sea monsters. In the book of Jonah the protagonist is famously swallowed whole by a “big fish” while trying to evade God’s prophetic call. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 18, 2021]

“The most terrifying biblical sea creature, however, is Leviathan, an enormous sea monster referenced in Psalmody, by the prophets Amos and Isaiah, and in the book of Job. According to some Leviathan was a sea serpent but some Jewish traditions refer to it as a “dragon” or just a monster.

A popular 19th-century theory speculated that it was a crocodile. According to the Rabbinic text Baba Bathra 75 Leviathan will be killed and eaten at the banquet that takes place at the end of time (the rest of it gets hung on the wall). Other Jewish legends about Leviathan preserved in rabbinic texts include the idea that it can make the waters of the ocean boil, smells dreadful, and is afraid of a small worm that gets in the gills of fish and kills them.

“In Christian tradition Leviathan is associated Satan and envy. His jaws are sometimes shown as the hellmouth, the gateway through which people descend into hell at the Last Judgment. Even serious theologians develop this theme: one prominent theory of salvation espoused by prominent bishop and saint Gregory of Nyssa in his Great Catechism pictures the devil as a large fish who swallows people when they die. After the crucifixion Satan mistakenly consumes Jesus on the assumption that he is just another human being. It’s a trap. Jesus becomes the fishhook by which Satan is forced to “bring up again” — i.e., vomit — all of the people he had previously swallowed. Call this the emetic theory of salvation, if you will (or its actual name the Christus Victor theory of salvation). Traces of this idea are found in Christian writers as early as the second century and show, as Kneebone argues for Oppian, the way that the sea monster is both a mythical prototype for everything bad and a plausible candidate for the terrors of the natural world.

Shark-Tooth Weapons From Around the World

Across the Pacific and beyond, many societies have incorporated shark teeth into weapons and ceremonial objects—especially coastal groups that frequently hunted sharks. When not worn as ornaments, shark teeth were often embedded into knives, clubs, spears, and lances used in combat or ritualised fighting. [Source: Adam Brumm, Michelle Langley, Adhi Oktaviana, Basran Burhan, Griffith University, and Akin Duli, Universitas Hasanuddin. The Conversation, October 2023]

Examples include:

• North Queensland: fighting knives with rows of shark teeth set along hardwood shafts.

• Mainland New Guinea, Micronesia, and Tahiti: lances, knives, and clubs armed with shark teeth; in Tahiti, lances also formed part of mourning regalia.

• Kiribati: famous shark-tooth daggers, swords, and spears used in highly ritualised—and often deadly—conflicts.

• Mesoamerica: shark teeth used for ritual bloodletting.

• Tonga, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Kiribati: shark-tooth tools used as tattooing blades.

• Hawaii: “shark-tooth cutters” used as concealed weapons and for preparing the remains of dead chiefs.

Although shark teeth appear in archaeological sites as far back as 39,000 years ago, most were likely personal ornaments, not weapons. Examples include perforated teeth from Buang Merabak and Kilu in Papua New Guinea and from Garivaldino in Brazil.

7,000-Year-Old Shark-Tooth Knives from Sulawesi, Indonesia

dogfish (a kind of shark) in a second-century BCE mosaic from a Roman house in PompeiiPhoto by Naples National Archaeological Museum

Excavations at a Tolean people site on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi have uncovered two rare and lethal artefacts dating back roughly 7,000 years—tiger shark teeth fashioned into blades. Reported in Antiquity, these discoveries represent some of the earliest evidence anywhere in the world for the use of shark teeth in composite weapons, tools constructed from several components. Previously, the oldest known shark-tooth blades were less than 5,000 years old. [Source: Adam Brumm, Michelle Langley, Adhi Oktaviana, Basran Burhan, Griffith University, and Akin Duli, Universitas Hasanuddin. The Conversation, October 2023]

Both teeth were found during a joint Indonesian–Australian excavation and come from sites associated with the Toalean culture—a mysterious foraging society that lived in southwestern Sulawesi from about 8,000 years ago until an uncertain point in the recent past. Using scientific analysis, experimental replication, and comparisons with recent Indigenous technologies, our international research team concluded that these modified teeth had once been mounted on handles. Their design and wear patterns suggest they served as weapons or ritual tools, rather than everyday knives.

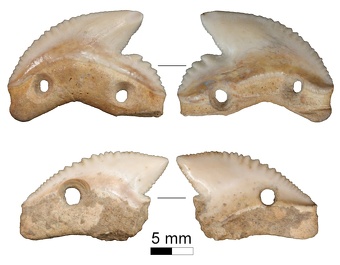

Each tooth came from a two-metre tiger shark (Galeocerda cuvier) and is similar in size. Both were intentionally perforated. One tooth from Leang Panninge has two holes drilled through the root. The other, from Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1, is broken but originally appears to have had two holes as well. Microscopic analysis revealed that both teeth had been securely bound to handles using plant fibres and a resin-like adhesive made from mineral, plant, and animal materials—a technique still seen in shark-tooth weapons used across the Pacific.

Although residue might suggest mundane use, ethnographic parallels, archaeological context, and experimental tests point strongly toward ritual or combat functions. Experiments showed that tiger shark teeth can slice deep, long gashes whether used in combat-style strikes or when butchering fresh pork. Their major drawback is that they dull quickly, making them impractical as everyday knives. This limitation, combined with their ability to produce severe lacerations, helps explain why shark teeth have historically been reserved for weapons and ritualised violence.

The Sulawesi teeth stand apart from shark-tooth weapons found in the Pacific region and other places. . Their deliberate shaping, perforation, and the microscopic traces of binding and adhesive indicate that they were mounted as blades—and almost certainly used in conflict or ritual cutting. Whether they sliced human or animal flesh, these shark-tooth blades from Sulawesi may represent the oldest known weapons of their kind in the Asia–Pacific, pushing back the origins of this distinctive technology thousands of years earlier than previously recognised.

Ancient Aboriginal Tiger Shark Stories and Language

Modified tiger shark teeth found in 7,000-year-old layers of Leang Panninge (top) and Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1 (bottom) on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi

The Aboriginal Yanyuwa people believe Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria was created by the tiger shark and developed a language that goes along with this belief. Georgina Kenyon of the BBC wrote: The tiger shark was having a really bad day. Other sharks and fish were picking on him and he was fed up. After fighting them, he met up with the hammerhead shark and some stingrays at Vanderlin Rocks in the waters of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria to speak of their woes before they set out to find their own places to call home. This forms one of the oldest stories in the world, the tiger shark dreaming. The ‘dreaming’ is what Aboriginal people call their more than 40,000-year-old history and mythology; in this case, the dreaming describes how the Gulf of Carpentaria and rivers were created by the tiger shark. The story has been passed down by word of mouth through generations of the Aboriginal Yanyuwa people, who call themselves ‘li-antha wirriyara’ or ‘people of the salt water’. [Source: Georgina Kenyon, BBC, May 1, 2018]

The tiger shark’s journey was challenging as he forged his way through the Gulf, creating the water holes and rivers in the landscape. He was turned away by many other angry animals who did not want him to live with them. A wallaby even hurled rocks at him when he asked if he could stay with her. But as he swam, the dreaming story explains, the shark helped create the waters of the Gulf of Carpentaria that we see today. “Tiger sharks are very important in our dreaming,” said Aboriginal elder Graham Friday, who is a sea ranger here and one of the few remaining speakers of Yanyuwa language. Some people here still believe the tiger shark is their ancestor.

The Aboriginal Yanyuwa people developed a language to go along with their belief about tiger sharks. In their ‘tiger shark language’, they have many words for the sea and shark. Georgina Kenyon of the BBC wrote: Yanyuwa is a beautiful, poetic language. Its rhythms sound like the sea it so perfectly describes. The language precisely expresses a sense of place, often describing complex natural phenomenon in a single word, showing how attuned the Aboriginal people are to nature. [Source: Georgina Kenyon, BBC, May 1, 2018]

See Ancient Aboriginal Language Shaped by Sharks Under EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Sharks, Melville, Hemingway and Roosevelt

In whaling stories and accounts by whalers sharks followed ships and fed on garbage, whale offal and carcasses that were thrown overboard. Sailors regarded them as harbingers of death when they showed up for no explainable reason. In “Moby Dick”,Herman Melville warned “they have a ravenous finger in the pie...It is deemed but wise to look sharp to them.” He call sharks “pale ravener of horrible meat” with a “saw-pit of mouth,” “ghastly flank” and “Gorgonian head.”

Ernest Hemingway and Franklin Roosevelt were avid shark fishermen. Hemingway liked to shoot them with a Thompson machine gun. Franklin Roosevelt hosted parties son his boat in which bait was laid out for sharks and guests took turns shooting at them with a revolver.

Hemingway cursed sharks that stole his catches and burned thousands of them on the beach. But sometimes he could not help but step back and admire them. Describing a mako shark breaking the surface in “The Old man and the Sea” he wrote, “Everything about him was beautiful except his jaws...He is not a scavenger nor just a moving appetite...he is beautiful and noble and knows no fear of anything.”

Image Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); Wikimedia Commons. Hook from Live Science, Neanderthal pictures from Atlas Obscura, ancient Peru from Natural History magazine

Text Sources: Shark Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, Global Shark Attack File (GSAF), National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025