SHARK REPRODUCTION

Sharks generally are: 1) oviparous (young are hatched from eggs) or viviparous (give birth to live young that developed from eggs in the body of the mother); 2) employ sperm-storing (producing young from sperm that has been stored, allowing it be used for fertilization at some time after mating); and 3) engage in internal reproduction in which sperm from the male fertilizes the egg within the female.

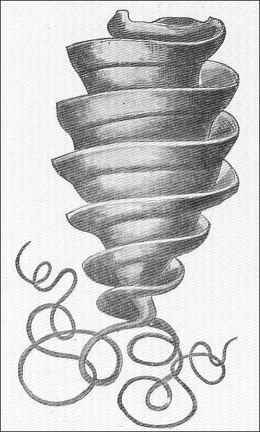

About 40 percent of shark species lay eggs and the remainder give birth to live young. These hatch from eggs inside their mother's body. Some species even give birth to fetuses with umbilical chords. Lemon sharks are among the species that give birth to live young. The gestation period for sharks varies between 6 and 24 months. Those that are born in eggs are often deposited leathery black sacks that are usually several inches long and sometimes are called "mermaid's purses." Baby sharks are called pups.

Sharks reproduce like humans by copulation and internal fertilization. This differs from most fish who engage in external reproduction in which the male’s sperm fertilizes the female’s egg outside her body. Cod and flounder lay eggs that are fertilized externally. Coastal bays, mangrove swamps, shallow reefs and atolls are favored breeding areas. These areas provide food-rich environments for the young sharks to develop. Pups emerge with a full set of teeth and an instinct to hunt.

Sharks have very slow reproductive rates. The females of most species of shark do not breed until they reach maturity at age of 10 to 20 years old and mate every year or every other year. Most sharks produce litters of 6 or 12 pups; nurse sharks give birth to 20 or 30; and hammerheads and tiger sharks sometimes produce 40 or more.

Very little is known about courtship behavior in sharks, especially pelagic (open ocean) ones. Of the more that 500 shark species known, only a couple dozen — if that many — have had their mating, courtship, pairing, copulation, and post-copulatory behaviors studied in any depth. Spot-tail sharks (Carcharhinus sorrah) females appear not select males on the basis of any physical characteristic or behavior. This suggests that many sharks mate with any available mate.

Related Articles: SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ;SHARK FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING TECHNIQUES AND FRENZIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF SHARKS: EARLIEST ONES. DINOSAUR-ERA ONES AND MEGALODON ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Shark Sex

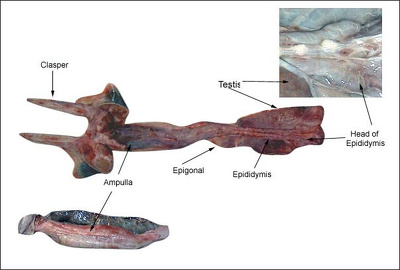

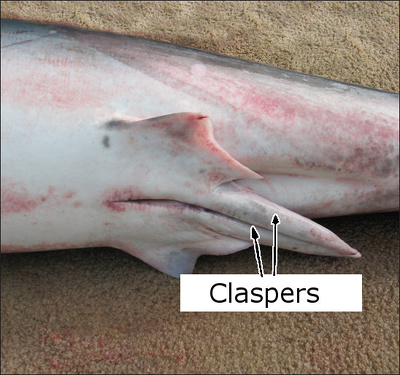

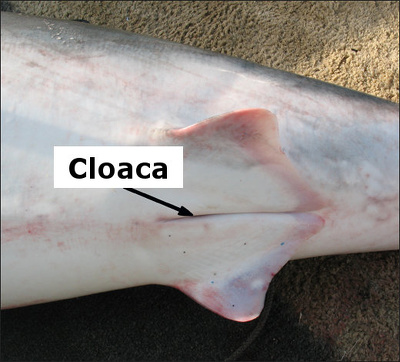

Male sharks and rays have paired reproductive structures called "claspers," located between and extending out from their pelvic fins. They are revealed when the male beats his the tail in one direction and moves his midsection in the other directions. A groove in each clasper directs sperm into the female's cloaca during mating. Sperm may fertilize the egg then, or may be stored until an egg is released. Claspers serve as both a penis and means of holding on to the female during mating.

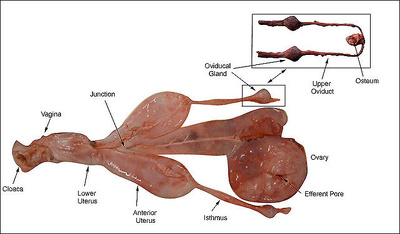

All male sharks possess two claspers but only one is used in copulation, with the choice dependent on which side of the female he grips.” Females have cloaca, an opening which is sort of like vagina but is closer to a storage area where fertilized eggs can develop. Females can store sperm for months. They also have a douche built into their sex organ that may allow it to wash out previously-deposited sperm.

Females often try to avoid males by retreating away from them or arching their body so the males can't grip her. Pairs or groups of males sometimes works together to trap a female and the male that can manoeuver into position the quickest gets the chance to copulate. Generally aggressiveness and persistence are more important for males than size in achieving success in mating but if a really big shark is patrolling about, females will often go limp and let the big shark mate with her.

When mating, male sharks bite female sharks to keep them stable. This results in mating scars on females. Male sharks sometimes bite the females hard on their lateral posterior before they mate. It is no surprise then that the females of some species of shark have skin twice as thick as the males. The nasty looking "love bites" usually heal quickly and completely.

Description of Mating Sharks

Sharks have only been observed mating a handful of times. At first it was though they copulated stomach to stomach, but in 1959 a scientist watched a pair of lemon sharks mating side by side, moving in synch, as if they were a "single monster with two heads." Until recently most of what was known about shark reproduction was based on chance encounters at sea or reports by fishing guides.

Describing a pair of nurse shark mating off the Florida Keys, Harold L. Pratt Jr. and Jeffrey Carrier wrote in National Geographic, "To subdue his partner, the male must seize the females' pectoral fin, flip her, and carry her from the shallows to deeper water...Suddenly a spray of seawater erupts from the surface — it's the male shark lunging for a female's fin — and a tail slaps the water with a percussive boom." [Source: Harold L. Pratt Jr. and Jeffrey Carrier, National Geographic, May 1995]

"Amid a swirl of fins we watched as the male struggled to arch his body over the female... Often one of his penis-like claspers poked out of the water, pointing skyward." The male then got a tight grip on female's fin and aligns his body with hers. "Thus anchored he can roll the female over, flick his tail underneath her to brace himself, and insert the clasper. Successful copulation lasts between one and two minutes."

"Afterwards, the male collapsed on the sea bottom. This evident fatigue may result from the fact that the male is deprived of oxygen the whole time he has his jaws clamped onto the female's fin. After days of mating, the female swims away with a chewed up pectoral fin." Less than 10 percent of attempts to mate by nurse sharks end in success.

Female Sharks Capable of Virgin Birth

The first recorded case of a female shark reproducing without a male was documented with a bonehead hammerhead shark at the Henry Doorly Zoo In Omaha in December 2001. The birth took place through parthenogenesis — asexual reproduction of an unfertilized egg — and is believed to have been prompted by a lack of males. During parthenogenesis — which sometimes occurs in bony fish but had never been seen in a shark before — the female eggs divides into two cells, which then fuse together and set off the development of embryos. The resulting offspring are genetically identical to the original egg.

Female sharks can fertilize their own eggs and give birth without sperm from males, according to a study on the asexual reproduction of the hammerhead at the Henry Dooly Zoo described above. The joint Northern Ireland-U.S. research, published in the Royal Society's peer-reviewed Biology Letter journal, analyzed the DNA of the shark born in 2001.The shark was born in a tank with three potential mothers, none of whom had contact with a male hammerhead for at least three years. Associated Press reported: Analysis of the baby shark's DNA found no trace of any chromosomal contribution from a male partner. Shark experts said this was the first confirmed case in a shark of parthenogenesis, which is derived from Greek and means "virgin birth." [Source: Shawn Pogatchnik, Associated Press, May 23, 2007]

“Asexual reproduction is common in some insect species, rarer in reptiles and fish, and has never been documented in mammals. The list of animals documented as capable of the feat has grown along with the numbers being raised in captivity — but until now, sharks were not considered a likely candidate. "The findings were really surprising because as far as anyone knew, all sharks reproduced only sexually by a male and female mating, requiring the embryo to get DNA from both parents for full development, just like in mammals," said marine biologist Paulo Prodahl of Queen's University of Belfast, Northern Ireland, a co-author of the report.

Before the study, many shark experts had presumed that the Nebraska birth involved a female shark's well-documented ability to store sperm for a lengthy period of time. Doing this for six months is common, while three years would be exceptional, they agreed. The lack of any paternal DNA in the baby shark ruled out this possibility.

Female Shark of Different Species Reproduces Without Males

A female shark separated from her long-term mate developed the ability to have babies on her own. Alice Klein wrote in New Scientist: Leonie the zebra shark (Stegostoma fasciatum) met her male partner at an aquarium in Townsville, Australia, in 1999. They had more than two dozen offspring together before he was moved to another tank in 2012. From then on, Leonie did not have any male contact. But in early 2016, she had three baby sharks. [Source: Alice Klein, New Scientist, 16 January 2017]

Christine Dudgeon at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, and her colleagues began fishing for answers. One possibility was that Leonie had been storing sperm from her ex and using it to fertilise her eggs. But genetic testing showed that the babies only carried DNA from their mum, indicating they had been conceived via asexual reproduction. Some vertebrate species have the ability to reproduce asexually even though they normally reproduce sexually. These include certain sharks, turkeys, Komodo dragons, snakes and rays. However, most reports have been in females who have never had male partners.

“There are very few reports of asexual reproduction occurring in females with previous sexual histories, says Dudgeon. An eagle ray and a boa constrictor, both in captivity, are the only other female animals that have been documented switching from sexual to asexual reproduction. “In species that are capable of both reproductive modes, there are quite a few observations of switches from asexual to sexual reproduction,” says Russell Bonduriansky at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. “However, it’s much less common to observe switches in the other direction.”

“In sharks, asexual reproduction can occur when a female’s egg is fertilised by an adjacent cell known as a polar body, Dudgeon says. This also contains the female’s genetic material, leading to “extreme inbreeding”, she says. “It’s not a strategy for surviving many generations because it reduces genetic diversity and adaptability.” Nevertheless, it may be necessary at times when males are scarce. “It might be a holding-on mechanism,” Dudgeon says. “Mum’s genes get passed down from female to female until there are males available to mate with.”It’s possible that the switch from sexual to asexual reproduction is not that unusual; we just haven’t known to look for it, Dudgeon says. Bonduriansky agrees. “It would seem to be highly advantageous,” he says. “It could be much more common than we currently realise.”

Trying to Uncover When and Where Sharks Give Birth

Hannah Verkamp wrote in The Conversation: “Many of the large iconic shark species — like great whites, hammerheads, blue sharks and tiger sharks — cross hundreds or thousands of miles of ocean every year. Because they’re so wide-ranging, much of sharks’ lives, including their reproductive habits, remains a secret. Scientists have struggled to figure out precisely where and how often sharks mate, the length of their gestation, and many aspects of the birthing process. I am hoping to answer two important questions: Where and when do sharks give birth? [Source: Hannah Verkamp, PhD Student in Marine Biology, Arizona State University, The Conversation, July 13, 2021]

Until very recently, the technology to answer these questions did not exist. But marine biologist James Sulikowski, a professor at Arizona State University developed a new satellite tag called the Birth-Tag with the help of the technology company Lotek Wireless. Using this new satellite tag, our team is working to uncover where and when tiger sharks give birth with hope the same technology can do the same for other large shark species.

“The Birth-Tag is a small, egg-shaped device that we insert into the uterus of a pregnant shark where it will remain dormant and hidden among the fetal sharks throughout pregnancy. Similar implanted tags have been used to figure out the birthing locations of terrestrial mammals, such as deer, for decades with great success. When a tagged mother shark gives birth, the tag will be expelled alongside the babies and float to the sea surface. Once it senses dry air, the tag transmits its location to a passing satellite, which then sends that location and time of transmission back to our lab. As soon as we download this information, we know where and when that shark gave birth.

We launched the first phase of the study in December of 2019 at the crystal-clear waters of Tiger Beach off Grand Bahama Island to tag tiger sharks. Tiger Beach is a hot spot for female tiger sharks of many different life stages, including large pregnant individuals. These pregnant females may be aggregating in the warm, calm waters of Tiger Beach to take refuge and speed up their gestation. The high number of pregnant sharks in this small area makes finding one much easier, but actually catching and bringing a 10-foot-plus shark to the boat is no easy task. We fish for the sharks using drumlines, and it can take several hours to safely catch, pull in by hand, and secure one of these powerful creatures next to the boat.

“Once we catch a female tiger shark, we first take several length and girth measurements to get an idea of her general health and to see if she is sexually mature. Then we check for bite marks, which are evidence of a recent mating event. After we collect this baseline information, we rotate her upside down to coax her into a trance-like state called tonic immobility. Tonic immobility is a natural reflex in many sharks that induces a state of physical inactivity. This keeps the powerful shark calm and still for the most exciting part of the workup, the part where my experience comes into play: the pregnancy check.

Shark embryos Just like the ultrasounds used on humans, we use a mobile ultrasound machine to figure out if a shark is expecting. I put on a pair of goggles that allow me to see everything the ultrasound sees, lean over the side of the boat, and place the probe onto the upside down shark’s abdomen. The image is usually fuzzy at first as water splashes over the shark and up onto the boat. The team holds the shark still as I slowly maneuver the probe along her belly. Then, if she’s pregnant, something magical happens.

“Wriggling baby tiger sharks, up to 40 of them packed tightly together inside their mother’s womb, appear in front of my eyes. We spy on them as they pump fluid through their still-developing gills, and we watch in awe as they wiggle around.Once we have enough data on the approximate size of the offspring — which gives us an idea of how far along the pregnancy is — it’s time to tag the mama shark.

“As I hold the probe as still as possible to keep a visual of the shark’s internal anatomy, Dr. Sulikowski takes the Birth-Tag and uses a custom-designed applicator to carefully insert it into the uterus through the urogenital opening. No surgery required, the tagging procedure is complete in a matter of minutes. Once the tag is inside the uterus, we rotate the shark upright to wake her and release her back to the open ocean.

In December 2020, we deployed the first Birth-Tags on three pregnant tiger sharks. For tiger sharks, pregnancy is thought to last 12-16 months, but researchers have little in the way of hard data. Since these tagged sharks ranged from recently mated to mid-gestation, an added bonus of this study is that it might help refine estimates of the length of pregnancy for this species. We are currently waiting to receive a notification from our online ARGOS satellite system that will alert us that one of our sharks has given birth. When that happens, we will be the first in the world to know, in close to real time, where and when tiger sharks give birth.

Shark Offspring and Cannibalism in the Womb

Baby sharks are called pups. They grow slowly. Until they reach maturity they are vulnerable to attacks from predators. A study of blacktip pups implanted with transmitters found that 90 percent died in their first year, most in the first four months of life.

Lemon sharks give birth to live young and breed in shallows and young sharks spend their first year around mangrove swamps, feeding on small fish and crustaceans and staying shallow waters were there are less vulnerable to attacks from larger fish, especially other sharks. In the Bahamas there are large numbers of youngsters living in mangrove swamps which offer them a plentiful supply of food and few dangers than in the open sea and around reefs.

Sharks are the only known animals in which embryos are cannibalistic within the womb. This fact was discovered by scientists who reached into the womb of a 12-foot sand tiger shark and were bitten. When the shark was dissected half-eaten baby sharks were discovered in the stomach. Most sharks practice intrauterine cannibalism produce only one pup per uterus. [Source: Eugenie Clark, National Geographic August 1981]

Baby sharks of many species break from their eggs while in their mother's stomach when they are about four inches long and swim around inside the uterus ripping open other eggs and eating the embryos. Female sand tiger sharks have two uteruses. The first born shark in each uterus often eats its siblings and the mother give birth to two 40-inch-long offspring.

First-ever Hybrid Sharks Discovered off Australia

A hybrid black tip shark containing both common and Australian black tip DNA was found in Australian waters in the earky 2010s.. Scientists hailed the discovery as the world's first known hybrid shark and said it could be an way predators were adapting to climate change. AFP reported: Scientists have identified the first-ever hybrid shark off the coast of Australia, a discovery that suggests some shark species may respond to changing ocean conditions by interbreeding with one another. A team of 10 Australian researchers identified multiple generations of sharks that arose from mating between the common blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus) and the Australian blacktip (Carcharhinus tilstoni), which is smaller and lives in warmer waters than its global counterpart. To find a wild hybrid animal is unusual,” the scientists wrote in the journal Conservation Genetics. “To find 57 hybrids along 2,000 km [1,240 miles] of coastline is unprecedented.” James Cook University professor Colin Simpfendorfer, one of the paper’s co-authors, emphasized that he and his colleagues “don’t know what is causing these species to be mating together.” They are investigating factors including the two species’ close relationship, fishing pressure and climate change. [Source: Juliet Eilperin, AFP, January 3, 2012]

Australian blacktips confine themselves to tropical waters, which end around Brisbane, while the hybrid sharks swam more than 1,000 miles south to cooler areas around Sydney. Simpfendorfer, who directs the university’s Centre of Sustainable Tropical Fisheries and Aquaculture, said this may suggest the hybrid species has an evolutionary advantage as the climate changes. As a result, he wrote, “We are now seeing individuals carrying the more tropical species genes in more southerly areas. In a changing climate, this hybridization may therefore allow these species to better adapt to different conditions.”

The researchers — who had been working on a government-funded study of the structure of shark populations along Australia’s northeast coast — first realized something unusual was going on when they found fish whose genetic analysis showed they were one kind of blacktip but their physical characteristics, particularly the number of vertebrae they had, were those of another. Shark scientists often use vertebrae counts to distinguish among species. The team also found that several sharks that genetically identified as Australian blacktips were longer than the maximum length typically found for the species. Australian blacktips reach 5.2 feet; common blacktips in that part of the world reach 6.6 feet.

Demian Chapman, assistant director of science of Stony Brook University’s Institute for Ocean Conservation Science, said the idea that sharks can interbreed is “something a lot of shark biologists thought could happen but now we have evidence, and it’s fantastic evidence.” He added, however, that the fact that these two species were so closely related made it easier for them to mate than wildly-divergent ones. “It doesn’t mean we’re going to see great-white-tiger sharks anytime soon, or bull-Greenland sharks,” he said. “If any species was going to hybridize, it was going to be this pair.” Chapman, who first documented in 2008 that some female sharks can reproduce without having intercourse, said this latest discovery suggests “there’s yet another path to reproduction that these species can do. It just reinforces that sharks can do it all when it comes to reproduction.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA, clasper and cloaca images from Canadian Shark Research Lab

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated August 2024