Home | Category: Shark Species

SHORTFIN MAKO SHARK FISHING

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “Makos” (shortfin makos) — are eagerly targeted by recreational fishermen and frequently caught as bycatch by commercial long-liners. Their meat rivals swordfish in quality, and their fins are prized in Asia for shark fin soup, a combination that has put makos under significant pressure. But how much pressure, and to what ultimate effect, is uncertain. Scientists have no clear idea how many makos there are in the Earth’s oceans, and most of the data on catch and mortality rates come from commercial fishing operations, which famously tend to underreport catches. So biologists studying makos are trying to fill in some huge knowledge gaps. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, August 2017]

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “Makos” (shortfin makos) — are eagerly targeted by recreational fishermen and frequently caught as bycatch by commercial long-liners. Their meat rivals swordfish in quality, and their fins are prized in Asia for shark fin soup, a combination that has put makos under significant pressure. But how much pressure, and to what ultimate effect, is uncertain. Scientists have no clear idea how many makos there are in the Earth’s oceans, and most of the data on catch and mortality rates come from commercial fishing operations, which famously tend to underreport catches. So biologists studying makos are trying to fill in some huge knowledge gaps. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, August 2017]

“The fishing pressures on makos are intense, Brad Wetherbee, the marine ecologist from the University of Rhode Island, who has tagged many makos, told National Geographic. The ones we were trying to catch swim northward up the Atlantic coast in the summer, and between everyday recreational fishing and the dozens of shark-fishing tournaments held between Maryland and Rhode Island, it’s a perilous journey for the sharks. “A lot of them have been weeded out by the time they get up to” Rhode Island, Wetherbee said.

On whether the catch rate is sustainable, Wetherbee said Makos, like many sharks, are especially vulnerable to overfishing because of their small litters and high age of sexual maturity. (One study suggests that female makos don’t reach maturity until around 15 years old or later, but these figures are not definitive. Biologists agree more research is needed.) “We don’t know,” he said. “These are far-ranging, international sharks — some of our [tagged] makos have gone into the waters of at least 17 different countries — and there’s not enough data for management agencies to come up with a good estimate of whether the population is going up or down or staying the same. There’s probably some number of mako sharks that would be fine to catch and kill. But we don’t know if it’s 100, or 1,000, or 100,000.”

Related Articles: OPEN OCEAN SHARKS: BLUE SHARKS AND OCEANIC WHITETIP SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; MAKO SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING AND SHORTFIN MAKO SPEED ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK SEX: REPRODUCTION, DOUBLE PENISES, HYBRIDS AND VIRGIN BIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING TECHNIQUES AND FRENZIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Shortfin Mako Shark Commercial Fishing in the U.S.

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “According to the National Marine Fisheries Service, which regulates fishing in U.S. waters, makos are being fished at a sustainable level. This assessment is based largely on catch figures supplied by commercial long-liners to the international organization that regulates fishing for tuna and other pelagic fish in the Atlantic, and those figures show a relatively consistent harvest over recent years, suggesting that mako populations are stable. But the figures are an imprecise measure. The catch is recorded in metric tons, and basic information like the number of sharks caught, and the size and sex of those sharks, can be missing. On top of that, many catches go unreported, leading scientists to question the reliability of both the data and the stock assessments. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, August 2017]

Most shortfin mako harvested in the U.S. come from the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. According to the 2017 stock assessment (and updated projections from 2019), shortfin mako sharks are overfished and subject to overfishing. As of July 5, 2022, U.S. fishermen may not land or retain Atlantic shortfin mako sharks, In 2020, commercial landings of Pacific shortfin mako totaled 1,678 kilograms (37,000 pounds) and were valued at $23,000, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. NOAA]

According to NOAA: U.S. wild-caught Pacific shortfin mako shark is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations. The population is above target population levels. The fishing rate is at recommended levels. According to the 2018 stock assessment, North Pacific shortfin mako shark is not overfished and not subject to overfishing.

Shortfin Mako Shark Commercial Fishing regulations in the U.S.

NOAA Fisheries and the Pacific Fishery Management Council manage the Pacific shortfin mako shark fishery on the West Coast. Permits are required to fish for highly migratory species, including shortfin mako sharks, and fishermen must maintain logbooks documenting their catch. Gear used to catch shortfin mako does not contact the ocean floor, so there is no impact to habitat. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.[Source: NOAA]

Fishermen are required to take a training course on safe handling and release of protected species. Fishing times and areas are tightly managed to reduce the risk of catching protected species, such as sea turtles, whales, and dolphins. Fishermen must use acoustic devices that emit high-pitched noises to deter marine mammals, and net extenders to increase minimum fishing depth on drift gillnet gear, to protect marine mammals.

The Shark Conservation Act requires that all sharks, with one exception, be brought to shore with their fins naturally attached. Management of highly migratory species, like mako sharks, is complicated because the species migrate thousands of miles across international boundaries and are fished by many nations. Two international organizations, the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), manage highly migratory species, like sharks, internationally. No international measures are in place specific to shortfin mako sharks, but both organizations have passed shark conservation and management measures that combat shark finning practices and encourage further research and periodic stock assessment efforts for sharks.

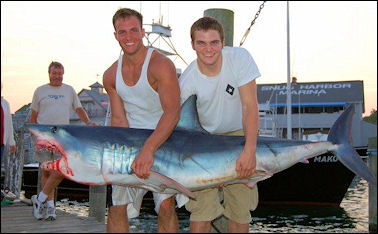

Mako Shark Sport Fishing

Shortfin mako’s a popular sport fishing fish. Noted for their leaping ability (makos have been known to clear the water by more than 20 feet), the fish have long been a target for anglers using conventional tackle. “When you’re fishing for makos, the sharks are hunting you, not the other way around,” Conway said. “They’re not shy; when they turn on, they’re like a heat-seeking missile.” [Source: Chris Santella, New York Times, July 12, 2010]

Time magazine reported in 1934: Scientists call the shark Isuris, most laymen call it "mackerel shark" (because it eats mackerel and looks a little like one) and New Zealand fishermen, who hate & fear it, call it "the great mako." It lives mostly in the South Seas and off New Zealand but, straying over the world, it has been seen as far north as Cape Cod. Largest ever caught was hooked off New Zealand in 1931 by one H. Wickham-White. It was 11 ft. 6 in. long, 6 ft. 2 in. in girth and weighed 798 Ib. No man-eating has been proved against the mako, but fishermen who have fearfully watched its great, jagged teeth snap their oars, rip off their rudders and crunch their boats' sides would rather not make the test. Fisherman Grey puts mako fishing in a class with tiger and elephant hunting for thrill and danger. Largest game fish ever caught with rod & reel was Zane Grey's 1,040-lb. marlin. But the mako is the only shark which will take fast-moving bait, and at leaping, it is unsurpassed. Tarpon and sailfish also leap clear of the water, but not so high. And like those of tuna and marlin which thresh on the surface, their bodies, gills, fins and tails quiver in the air. The mako soars up stiff as a poker. For a moment it hangs motionless at 20 or 30 ft., blue of back, white of belly; its great pectoral fins spread wide. Then it flips over, falls back broadside to the sea with the splash of a wrecked airplane. [Source: “Animals: Sharks by Grey”, Time magazine, May 14, 1934]

Historically, makos brought to the boat have often been killed. But given the startling decline in shark populations, many sports anglers are now practicing catch-and-release fishing. Recreational charter vessel operators must keep logbooks documenting their catch, and there is a limit on the number of mako sharks recreational fishermen can catch. [Source: NOAA]

Though makos are generally found far offshore, the waters bordering San Diego serve as one of their primary breeding grounds. Juvenile sharks — fish up to 300 pounds — frequent the inner coastal waters during the summer, feeding on yellowtail jacks, bonitos and other forage fish. Makos are sometimes encountered disturbingly close to shore, even within a quarter-mile of the beach off La Jolla.

Zane Grey and Mako Shark Fishing

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “Zane Grey made his name writing adventure novels about the American West, but his real love wasn’t gunslinging or cowpoking; it was deep-sea fishing. He held 14 world records for catching saltwater fish, including the first billfish over 1,000 pounds landed with a rod and reel, a marlin he caught in Tahiti in 1930. But nothing compared to the shortfin makos he encountered off the coast of New Zealand in 1926. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, August 2017]

“The first mako Grey got on the line was a 258-pounder, and when he reeled it to the side of the boat, “quickly I learned something about mako!” he wrote in his book Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado, New Zealand. “He put up a terrific battle, broke one gaff, soaked us through with water, and gave no end of trouble.” Once the shark was landed, Grey marveled at its build — streamlined, muscular, with a head like a bullet. “I had never seen its like,” he wrote. “Every line of this mako showed speed and power.”

“But it was the 1,200-pounder that the captain of his boat battled that led to almost mythical superlatives. After a long fight in which the mako “leapt prodigiously and made incredible runs,” the shark bit through the leader and escaped. “I was terrified,” the captain told Grey. “It seemed that mako filled the whole sky. He was the most savage and powerful brute I ever saw, let alone had on a line!”

In dramatic account of a mako landing in his fishing boat, Grey wrote in in Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado, New Zealand (1926): ‘A mako so huge that he absolutely paralysed me with terror emerged with a roar of water to go high in the air. … He was all white underneath and his huge pectorals stood out four feet on each side of him. I could see the black eyes standing out from the sides of his head. He dropped down on the boat with a sudden crash, almost capsizing the launch. I was thrown from my chair, and, crawling back, I leaped up with difficulty regaining my feet. The launch righted itself, but the mako hung over the stern and covered it completely. … He looked at least seventeen feet long and large around as a hogshead, very dark blue in hue, with the most enormous head I ever saw on a sea monster. His long nose pointed right at me. A peculiar feature of the mako, like that in a thresher shark, is that his eyes stand out prominently from the sides of his head and these were fully as large and round as half a grapefruit. They were intensely black and full of fiendish fire. I knew that mako saw me just as well as I saw him. He opened enormous jaws lined with curved, white fangs. I saw where the big hook had stuck in him, and it seemed to my distorted senses that those jaws could take in a coal scuttle, and at that instant he shut his jaws with a convulsive snap like that made by a two-foot bear trap.’ [Source: Zane Grey, Angler’s Eldorado: Zane Grey in New Zealand. Auckland: Heinemann Reed: 1990, p. 150]

Fly Fishing for Mako Shark

Chris Santella wrote in the New York Times, “The notion of fly-fishing for sharks seems as if it were the product of an overactive (and likely distraught) imagination — perhaps a scribbling from Hunter S. Thompson’s notebook after a cocktail of espresso and mescaline. [Source: Chris Santella, New York Times, July 12, 2010]

“In the early “90s, I discovered saltwater fly-fishing and soon learned that sharks were among the most plentiful sport fish off the coast of Southern California,” Conway Bowman told the New York Times, “I bought a 17-foot aluminum boat and began pursuing them. After catching 25 blue sharks on my first day out with a fly rod, I realized I was on to something. It took me two years longer to figure out how to get mako sharks to take the fly. Nowadays, if I can draw a mako near the boat, we’re almost certain to hook them.”

Suffice it to say, fly-fishing for mako sharks is not a dainty game. In addition to the telephone pole of a fly rod, reels are outfitted with 800 meters of backing, a stainless-steel leader and foot-long blaze-orange flies tied on 8/0 hooks. On an average day, Bowman will motor a few miles offshore to a spot where a current moves through. The current will broadcast a chum slick, which has a smell that draws sharks close. Our chum was an unappetizing stew of yellowtail carcasses, seasoned with a few tablespoons of menhaden oil. Once the chum bucket is over the side of the boat, the engine is cut and the waiting begins. It sometimes takes a while for a shark to appear; sometimes, its appearance is almost instantaneous.

Casts do not need to be long or terrifically accurate; the shark will generally find any fly in a five-foot radius. Once the shark bites down on the fly, get ready: some fish will take out 300 to 400 meters of line in a run. Put another way: you know you’re not fighting a 10-inch brook trout.

Catching a Mako Shark

Reporting from off the coast of San Diego, Chris Santella wrote in the New York Times, “My angling companion Geoff Roach’s exclamation: “We’ve got one coming in!.” Peering over the starboard gunwale, I spied the dorsal fin and then full profile of a shortfin mako shark. The fish — 80 pounds, our guide, Conway Bowman, guessed — swam alongside the skiff, then circled away. Bowman cast a teaser bait, a rubber orange squid without a hook, 50 feet off the boat and slowly retrieved. The shark reappeared, its dorsal fin breaking the surface. “Cast at the teaser,” Bowman called as the shark accelerated. [Source: Chris Santella, New York Times, July 12, 2010]

Grabbing a hardy 14-weight fly rod, I slapped a 25-foot cast near the bait. Bowman pulled the teaser away as I stripped the fly. Not 12 feet from the boat, the mako engulfed the fly. I stripped the fly line hard to set the hook in the shark’s tough jaw. It shook its head once, twice, as if in disbelief at what was happening, then began screaming line off the reel. Fifty meters away, the shark leapt into the air, its nose eight feet above the water. For a moment, its blue-black body was suspended parallel above the gray Pacific.

After 15 minutes of pitched battle, which left a dark bruise on my hip where I had leveraged the rod’s fighting butt, the fish was alongside the boat. Bowman grabbed the leader with a gloved hand and slid a release device (somewhat like a dentist’s tool) down the wire to the barbless fly. With a deft flip of his wrist, the fly popped out and the shark slowly swam away. With luck, it would one day grow large enough to swim the open waters of its birthright.

600-Kilogram (1,323.5-Pound) Mako Caught off Los Angeles

In June 2013, a 600 kilogram (1,323.5-pound) mako shark was caught in the waters off Huntington Beach, near Los Angeles, as part of taping for the reality show "The Professionals" on the Outdoor Channel. Conservationists are upset that the shark was caught while scientists viewed the catch as golden opportunity opportunity to study species behavior. [Source: Anh Do, Kate Mather and Joe Mozingo, Los Angeles Times, June 4, 2013]

The Los Angeles Times reported: "Yeehaw!" the sportfishermen yelled when they saw the fins slice the gray channel water off Huntington Beach. The chum of chopped mackerel and sardines had worked. The fight was on — and so were the cameras. The way they tell it, they hooked a giant mako and Jason Johnston, from Mesquite, Texas, got in the pole harness to reel it in. He grunted and slipped and slid for 2 1/2 hours as the shark ran the line out almost a mile, thrashing and jumping 20 feet in the air. They finally pulled it to the side of the boat, the Breakaway, and tied it up with a steel cable.

By the time they hauled it to Huntington Harbour and had it weighed at a processing plant in Gardena, they realized they appeared to have broken a record for the largest mako to be caught by line, 1,323.5 pounds. The men posed next to the cobalt blue fish and opened its jaws, revealing its dagger-sharp rows of teeth to the cameras. They breathlessly recounted how, if anything went wrong, they would have ended up as "lunch" or "at the bottom of the sea." Johnston, 40, described it to one television reporter as "a gigantic nightmare looking to reap horrible terror on anything it comes across."

But even before it became clear that the catch was for a reality show, plenty of people wondered why they really had to kill such a magnificent animal. Wouldn't just pulling it close and photographing it have been enough? Ben Ahadpour, who owns the marina the fisherman left from, said the captain of the boat, Matt Potter, 33, of Huntington Beach, knew the dock rules prohibited bringing in sharks. "He shouldn't have done that," Ahadpour said. "They could have done a catch and release. They can bring it up close, take a picture and let the shark go. But I guess they're so excited about their catch and getting his two minutes of fame."

Keith Poe, a sportfisherman who tags and releases sharks for conservationists, said that most anglers are releasing sharks these days, but might keep a potential record-breaker . "I wouldn't keep it, but the general sportfishing community would say it's acceptable," Poe said. Potter, whose nickname is "Mako Matt," doesn't buy any of the criticism, adding that he unloaded the shark at a public dock — not the marina. "It's just like any other fishing. The state limit for mako is two per person per day." He said he had five passengers out for three days and kept only the big shark. And he said he did not break the marina's rules because he used the public docks.

‘Hell of a Fright’ as Mako Jumps Into Fisherman’s Boat

A shark surprised a group of fishermen in New Zealand when it leaped onto their boat, video shows. The Miami Herald reported: Ryan Churches, the owner of Churchy’s Charter NZ, took a group fishing off the coast of Whitianga in November 2022, the skipper told the New Zealand Herald. Something snagged the fishermen’s bait and they began fighting the creature. Moments later, “we got a hell of a fright,” Churches told the New Zealand Herald. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft,Miami Herald, November 8, 2022]

A Mako shark launched itself onto the front of their boat, video shows. The shark landed with a loud thump and thrashed wildly about, hitting the window and scaring the fishermen on the other side of the glass. Churchy’s Charter shared a video of the “crazy moment” on Facebook. The shark was about 8 feet (2.5 meters) long and weighed about 150 kilograms (330 pounds), Churches told the New Zealand Herald. As it struggled to get back to the water, the fishermen became increasingly worried they might need to help free the shark, the skipper said.After a few minutes of thrashing, the shark managed to wiggle itself back into the water, Stuff reported. Whitianga is about 70 miles east of Auckland on New Zealand’s North Island.

According to People: The charter group went cruising in the open ocean, looking for kingfish, but a giant mako shark took the bait. "He got away safe. There's nothing much we could do. We can't go up the front to go near it because they go absolutely bonkers," Churches said. "We dropped the anchor down a little bit because it seemed to be holding it in place [on the boat]. He went absolutely bonkers again and pushed himself through the bow rail and slid back into the water." Churches added that all the humans aboard his boat left the experience unscathed and "were counting their blessings he [the shark] didn't land on the back of the boat," where all the passengers were gathered. [Source: Kelli Bender, People, November 19, 2022]

Mako Fishing Tournament

Glenn Hodges went to the Maryland shore for Mako Mania, an annual shark-fishing tournament held at the Bahia Marina in Ocean City. He wrote in National Geographic: This Mako Mania should not be confused with the Mako Mania tournament in Point Pleasant, New Jersey — or, for that matter, with the Mako Fever tournament in New Jersey or the Mako Rodeo tournament, also in New Jersey, or with any of the other 65 or so U.S. tournaments that include prizes for pelagic sharks like makos, threshers, and tiger sharks. After Jaws hit theaters in 1975, tournaments popped up along the eastern seaboard, and ever since, summer has not been a good time to be a shark in the North Atlantic. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, August 2017]

“I arrived at the marina just as the first sharks were being brought to the docks. It was a festive scene — hundreds of people eating and drinking and cheering for the anglers and their kills. Next to me a woman and a young boy watched as a 282-pound mako — the winner in the mako category, it turned out — was hoisted to be weighed. The anglers pulled up the snout for photographs, and the woman turned to the boy and said, “This is really cool, right?” The boy nodded silently, transfixed by the shark’s bloody grimace.

“As the sharks continued rolling in — 147-pound mako, 466-pound thresher, 500-pound thresher, 174-pound mako — I talked with the tournament’s organizer, Shawn Harman. “What’s more fun than seeing sharks?” he asked, surveying the cheering crowd. When we got to some of the knottier questions about the controversy over “kill tournaments,” as critics call them (versus “no kill” or “catch and release” tournaments, which are rare but do exist), he explained that his tournament was not like those of old — back in the 1970s and ’80s, when the sharks would pile up on the docks and go wholesale into the Dumpster afterward. Here, the only sharks brought to the dock were threshers and makos, the best tasting sharks in the ocean, with minimum sizes and a catch limit of one fish per boat per day. (Over the course of three days, 16 sharks were brought to the dock to be weighed.) “Nobody’s wantonly killing fish here. Everyone here eats what they kill.”

“I asked him where I might find mako on the menu, to see what it tastes like, and he fetched a fillet from one of the sharks just brought in, had it blackened, and served it to me on a bun with wasabi mayo. It was delicious — as good as any billfish I’d ever had. But the tasty sandwich and the festivity of the scene could not entirely conceal the problematic nature of the event. Later in the day, one of the fishermen told me that a 500-pound thresher shark brought in earlier had been pregnant, and when it was gutted, the tournament staff tried to hide the pups from the crowd. Threshers, like makos, are considered “vulnerable”.

Problems with Mako Fishing

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “The captains of the boats I went out in for those tagging operations in Maryland and Rhode Island are both longtime shark fishermen. They are not reflexively against the capture and killing of fish, and they are not squeamish about what deep-sea fishing entails. But both men have qualms about how sharks are being fished. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, August 2017]

“Mark Sampson, the Maryland captain, started a prominent shark-fishing tournament in Ocean City in 1981 and ran it for more than three decades. But he became increasingly concerned about the conservation of shark populations, so he made his size limits more restrictive to reduce the number of sharks caught. He also insisted that anglers use “circle hooks,” which, in contrast to conventional “J-hooks,” don’t lodge in a shark’s stomach when swallowed and result in fewer unnecessary killings. Some fishermen balked, participation declined, and because of the higher size limits, he said, “we had days in our tournament where not a single shark was brought back to the dock. “That’s not the recipe for a successful tournament, because people want to see those fish being brought in and weighed,” Sampson said. He shuttered his tournament in 2014, and he doesn’t accept charters for anglers who want to use his boat to participate in other shark tournaments.

“Charlie Donilon, the Rhode Island captain, has run shark-fishing charters since 1976. Where Sampson is quiet and circumspect, Donilon is talkative and emotional, and on one of those days in August when we were on the boat waiting for the fish to bite, he told me about the time a client reeled in a mako that refused to go gently. “I threw a harpoon in it, then I hit it with a flying gaff, and then tied it down to a side cleat, and the thing is scratching and blasting blood everywhere, and it’s all being recorded by the client. The guy sent me the video, and I watched it with my wife, and she asked, ‘Does that bother you?’”

“It did, he said, and he started trying to persuade his customers to release the sharks they caught. “I’d tell people, a 100-pound mako is just a tot, just a kid, because they have the potential to grow to 1,000 pounds or more. So I’d really like to let it go, because it’s an immature fish.” But since almost all the makos they catch out there are juveniles, it stopped making sense to even ask the anglers. So in 2015 Donilon instituted a catch-and-release policy, no exceptions. His business has taken a hit. “I’m way off what I used to be,” he said.

“Donilon accepts the loss of business because it doesn’t seem to him that the fishing is sustainable, no matter what the government says. “The sharks we tag, there’s like a gantlet they have to go through coming up the coast. They’ve got to go through Maryland, New Jersey, Long Island, Massachusetts — and everyone in the world is out there fishing,” he said. “They’ve got to be at least 15 years old in order to reproduce, the females. Now what are the odds of that shark making it up here 15 times without being caught? Pretty slim.”

“I thought of all the blue sharks we’d seen with hooks in their mouths, and it seemed to me he was right: pretty slim. Although most of the tagging study’s casualties had been killed by commercial fishermen in international waters — not by recreational fishermen — the Fisheries Service’s statistics attribute the majority of the mako kills in the U.S. to recreational fishermen. So who is fishing too much, and where? Empirically, it’s still too soon to say. But Donilon, at least, doesn’t need to wait for more data to render his verdict. “I did my share of killing,” he said one afternoon on the boat. “You know how there might be a guy in Africa who used to be a poacher, and he used to kill all the lions …” And as he said this, his eyes teared up and his voice started quivering, and finally he choked out a half whisper: “You’ve got to give back. We just take, take all the time …”

Mako Attacks

Shortfin Mako sharks (Isurus oxyrinchus) have accounted for nine non-fatal shark attacks and one fatal attack for of total of 10 attacks. Mako sharks are popular targets of sport fishermen and many of the attacks associated with them are provoked attack connect with fishing or chumming the water with bloody fish parts to attract them. [Source: International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, 2023]

In March 1999, a New Zealand fisherman needed 38 stitches in his leg after a 1.3 meter mako leapt up from the floor of his boat and sank its teeth into his thigh. They victim said the damage could have been far worse as the shark had first tried to bite him in the groin. "The accident happened after a friend accidentally gaffed the shark by the tail instead of the head as he dragged it on to their vessel," the victim said. The "fellow fishermen managed to beat the shark off with a club as blood poured from the wound."

In December 2019, a swimmer in Egypt lost his leg is a rare attack by a mako shark. Men’s Journal reported: A group of friends rented a motorboat to cruise in the Gulf of Suez according to the Daily News Egypt. They were nearly four miles offshore when Omar Abdel Qader, 23, jumped in for a swim. A mako shark attacked him, injuring his leg so severely it required amputation. In a conflicting report, the state-owned Al-Ahram newspaper reported that the swimmer was less than 200 yards offshore, according to Mada Masr. [Source: Men's Journal, December 5, 2019]

"Mako sharks are very shy, and have always inhabited deep offshore waters, far from the shoreline," Mahmoud Hanafy, a marine biologist at Suez Canal University, told Mada Masr. "Human is not on the menu for sharks." Hanafy suggested that overfishing and dumping food from boats can greatly increase the likelihood of a shark attack; scarcity of food for the sharks can too. "There is a huge competition between sharks and humans for the fish stock," Hanafy said. "With overfishing, it is expected that sharks will increase their feeding grounds and go to unusual places like inshore areas." In some instances, Hanafy added, some boat operators bend the rules against chumming to satisfy thrill-seeking tourists who are enamored with sharks.

The Associated Press reported that two officials investigating this attack said the swimmer jumped in after bait was thrown nearby, as the group combined swimming with fishing in the same spot. Egypt subsequently imposed a 15-day ban on fishing and offshore swimming near Ain Sokhna, a popular Red Sea tourist destination located 75 miles east of Cairo where the attack occurred, the Associated Press reported.

Tagging Endangered Mako Sharks

By some estimates the number of shortfin mako sharks declined by 38 percent beween 1972 and 2020. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) lists shortfin makos in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but may become so unless trade is closely controlled throughout itts range. [Source: NOAA, Mónica Serrano and Sean McNaughton, National Geographic, July 15, 2021]

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “In the summer of 2015 I was invited to join a mako-tagging operation off the Maryland coast. On each trip I accompanied scientists affiliated with the Guy Harvey Research Institute, which has been tagging and tracking makos in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico since 2008, with the primary objective of studying the sharks’ movement patterns. Makos in the western North Atlantic are highly migratory, traveling northward during the warmer months and then south as winter approaches. The excursions off Maryland’s coast in May were a resounding success: Over two weeks, 12 makos were fitted with satellite transmitters. By contrast”, earlier Rhode Island excursions with scientist Bradley Wetherbee “in August were a resounding failure: one week, zero makos. But that contrast offered a clue as to what might be happening with makos in the Atlantic. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, August 2017]

“What Wetherbee and his team do know is that the sharks they’re tagging are not faring well. The tags they use — about the size of a Zippo lighter, mounted on the dorsal fin — send signals to satellites every time the sharks surface, allowing researchers to create detailed maps of their movements. When the signals start coming from land, they know the sharks have been caught. “We’ve tagged 49 makos, and 11 have been killed,” Wetherbee told me. (Within a month, that number had increased to 12.) I said that seemed like a lot, and he agreed: The sample size is small, but the catch rate is troubling.

“Back on land, I called Mahmood Shivji, the Nova Southeastern University scientist who leads the tagging project. “What amazes me,” he said, “is that it’s a vast ocean out there and these animals move a lot, and yet these tagged animals are running into fishing hooks to the tune of 25 percent. No shark fishery can sustain a 25 percent removal every year.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023