Home | Category: Shark Species

HAMMERHEAD SHARK SPECIES

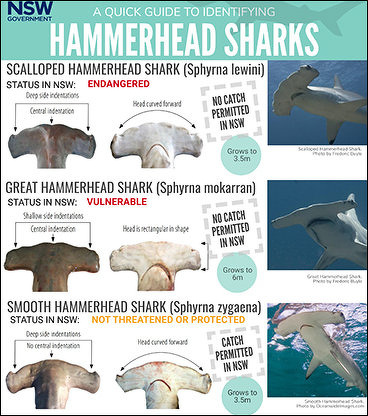

There are nine species of hammerhead, including smooth and scalloped hammerheads. They are often difficult to tell apart. Great hammerhead sharks often hunt stingray and pin them to the ocean bottom with side their heads.

Hammerhead sharks vary in size and in the shapes of their heads. Some have very wide heads relative to their bodies. These include the great hammerhead, winghead shark, scalloped hammerhead, smooth hammerhead, and Carolina hammerhead. Others have smaller hammers relative to their bodies, including the scoophead shark, bonnethead, small-eye hammerhead and scalloped bonnethead. The narrowest hammer belongs to the bonnethead shark. [Source: Gavin Naylor, Director of Florida Program for Shark Research, University of Florida, The Conversation, July 25, 2022]

The smooth hammerhead reaches length of four meters and 400 kilograms. It is found in tropical, subtropical and temperate waters throughout the world and give birth to live young. They are common in inshore waters near the surface with their dorsal fin knifing through the water. The smooth hammerhead can be distinguished from other hammerheads by the narrow blades of its hammer and the long upper tail lobe.

Related Articles: OPEN OCEAN SHARKS: BLUE SHARKS AND OCEANIC WHITETIP SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HAMMERHEAD SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, HEADS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK SEX: REPRODUCTION, DOUBLE PENISES, HYBRIDS AND VIRGIN BIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING TECHNIQUES AND FRENZIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Nine Hammerhead Shark Species

Hammerhead Shark Species

Common names — Scientific name — IUCN Red List status — Population trend — References

1) Great hammerhead — Sphyrna mokarran — Critically Endangered — Decreasing

2) Scalloped hammerhead — Sphyrna lewini — Critically Endangered — Decreasing

3) Smalleye hammerhead — Sphyrna tudes — Critically Endangered — Decreasing

4) Smooth hammerhead — Sphyrna zygaena — Vulnerable — Decreasing

5) Scalloped bonnethead — Sphyrna corona — Critically Endangered — Decreasing

6) Bonnethead shark — Sphyrna tiburo — Endangered — Decreasing

7) Winghead shark — Eusphyra blochii — Endangered — Decreasing

8) Scoophead — Sphyrna media — Critically Endangered — Decreasing

9) Carolina hammerhead — Yet to be assessed — Unknown [Source: Wikipedia]

Bonnethead sharks (Sphyrna tiburo) are also known as bonnet sharks or shovelhead. They are small members of the hammerhead shark genus Sphyrna and are abundant in the littoral zone of the North Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. They are the only shark species known to display sexual dimorphism in regard to the shape of the head, and is the only shark species known to be omnivorous and feed on plants.

Great Hammerhead Sharks

Great hammerhead sharks (Scientific name: Sphyrna mokarran) occur in all tropical waters worldwide, including waters around oceanic islands, the Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean and Pacific Ocean. They reside in both the open ocean and shallow coastal waters and you can sometimes see find them at reefs. During summer they may make small migrations towards more northerly areas. [Source: Robin Street, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Great hammerheads range in weight from 400 to 460 kilograms (881 to 1013 pounds). According to Animal Diversity Web: They posses a virtually straight anterior margin of the head with a deep central indentation. They have high second dorsal fins and the pelvic fins have curved rear margins. The teeth are triangular with extraordinarily serrated edges, becoming increasingly oblique toward the corners of the mouth. Their coloration varies from deep olive green to brownish grey above and white below. They are generally 4 to six meters in length. /=\

Great hammerhead sharks feed on rays, smaller sharks, and many species of bony fishes. Little is known about their behavior or social systems. Unlike scalloped hammerhead sharks, they are solitary hunters and considered dangerous to humans. The great hammerhead are larger and more aggressive than most hammerheads. They occasionally engages in cannibalism, eating other hammerhead sharks, including their own young.

Great Hammerhead sharks are viviparous, meaning they give birth to live young that developed in the body of the mother. Females reach sexual maturity at a length of three meters (10 feet). They give birth to litters of between 20 and 40 pups. Young are born in the summer season and are approximately 70 centimeters (two feet) in length at birth. The head shape of newborn pups is more rounded than that of adults. The shape changes as they grow. /=\

Scalloped Hammerhead Shark

Scalloped hammerhead sharks (Scientific name: Sphyrna lewini) are moderately large sharks with a global distribution. Also known as cornuda; mano kihikihi, they weigh up to 152 kilograms (335 pounds), reach lengths of up to 3.4 meters (11 feet) and have a lifespan up to 30 years. Their most distinguishing characteristic is their "hammer-shaped" head.

The lifespan of scalloped hammerhead sharks in the wild is typically 10.5 years but they live up to 55 years. The oldest known scalloped hammerhead was 31.5 years old, and was caught in the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Brazil. The authors of one study estimated the maximum lifespan of these sharks was 55 years. In a separate study conducted off the coast of Sinoloa, Mexico, the oldest individual sampled was approximately 10.5 years old.[Source: Erick Ruiz and Sierra Trujillo, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Scalloped hammerhead sharks are threatened by commercial fishing, mainly for the shark fin trade. They are also caught as bycatch by commercial fishermen fishing for other kinds of fish. Two distinct population segments of the scalloped hammerhead shark are listed as endangered and two are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).[Source: NOAA]

Scalloped Hammerhead Habitat and Where They Are Found

Scalloped hammerheads are pelagic (living in the open ocean, far from land) sharks that are found worldwide in temperate, tropical, saltwater and marine environments. They are sometimes observed in coastal areas, reefs and sea bottoms as well as in estuaries. They are typically found at depths of five to 525 meters (16.4 to 1722 feet), at an average depth of 268 meters (879feet). [Source: Erick Ruiz and Sierra Trujillo, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Scalloped hammerheads are found in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans and the Mediterranean Sea., between 40°N and 36°S latitude. Although they are found primarily in open marine waters, they can also be found near continental and island shelves and often enter bays and estuaries as well. /=\

Scalloped hammerheads migrate between different habitats at different times of the day. At dawn, they move from their offshore hunting grounds to island shelves, seamounts, and enclosed bays and estuaries. During the day they migrate to drop-off zones and reefs where females form schools for the purpose of social interaction. At dusk the sharks return to offshore pelagic areas and actively search for food. /=\

Scalloped Hammerhead Characteristics and Behavior

Scalloped hammerheads reach a weight from of 152.4 kilograms (335.7 pounds) and a length of 4.3 meters (14.11 feet). Females are larger than males. These sharks are natatorial diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), solitary and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They communicate with vision and sense using vision, touch, sound. vibrations, electric signals and magnetism and move regularly through a reasonably well-defined area as a result of their daily movement patterns. [Source: Erick Ruiz and Sierra Trujillo, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Scalloped hammerhead school

According to to Animal Diversity Web: Scalloped hammerheads have a small but prominent notch in the center of their characteristically-shaped head, which also bears pronounced grooves along its anterior margin, giving this species its common name. The side “wings” of the head are relatively narrow and are swept backwards. The first dorsal fin is larger than the second and is sickle-shaped, with a rounded tip, while the second dorsal fin has a concave rear edge. Both the pectoral and dorsal fins are slightly rounded. The tips of the pectoral fins are either a dark grey or black. The caudal fin is heterocercal and forked. Body coloration in this species displays typical pelagic countershading, with a grey dorsum and a white ventral surface. /=\

Both male and female adults may be found alone, in pairs, or in schools. However, most females are found in sexually segregated schools with larger, more mature females in the center. Young scalloped hammerheads live in large schools until they reach maturity. Adult males almost exclusively enter schools when in search of a mate. Pacific scalloped hammerheads are able to follow geological fault lines along the ocean floor. Recently cooled magma forms rocks that have a strong magnetic signal, which the animals follow to the locations where they form congregations to feed, school, and mate. (See Hammerhead Schools Above) /=\

Sharks are able to visually display aggression, submission, and dominance to conspecifics. When provoked or threatened, an individual will point its pectoral fins downward and arch its back. Sharks indicate submission by rapidly shaking their head side to side. Dominant sharks exhibit a “corkscrewing”, or upward swimming pattern, and will ram submissive sharks with their snout. /=\

Scalloped HammerheadFood, Eating Behavior and Predators

Scalloped hammerheads adults live in deeper oceanic waters, feeding on shallow-water and near-surface open water fishes and cephalopods (squid, octopus and cuttlefishes), lobsters, shrimps, and crabs, as well as various smaller sharks and rays. Younger individuals tend to feed in coastal waters, on shallow water and benthic ( on or near the bottom of the sea) fish. Hammerheads located in the Indo-West Pacific have been seen preying on sea snakes. [Source: Erick Ruiz and Sierra Trujillo, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Scalloped hammerheads actively forage for food during the night, using a “smash and grab” feeding technique. They accelerate towards prey and either swallow it whole, or disable prey by biting it. Great hammerheads (Sphyrna mokarran) have been observed using their hammer-like head to pin stingrays to the ocean floor before consuming them, and it is thought that scalloped hammerheads may use the same technique. Like all sharks, scalloped hammerheads use their eyes for visual perception, and nares for detection of chemical cues. They have special electroreceptors (sensory organs) called Ampullae of Lorenzini on the underside of their snout and "hammer". , and aid in the detection of buried prey, as well as navigation (by sensing changes in the Earth's magnetic field).

In the Gulf of California, male hammerheadss were caught at 25 meters while females of a similar size were discovered at a depth of 50 meters. It has been suggested that females may grow more rapidly and mature at a larger size than do males due to differences in food availability between these habitats. /=\

While scalloped hammerheads are fairly large sharks and top predators, they are occasionally preyed on by larger tiger sharks, great white sharks and orcas. For defense, scalloped hammerheads have countershading, which serves as camouflage in open water, with a grey to bronze colored back side and a pale white-grey underside. Scalloped hammerhead females form schools — occasionally with a few males — which lowers an individual’s chance of being attacked by a predator.

Scalloped Hammerhead Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Scalloped hammerheads are viviparous (they give birth to live young that developed in the body of the mother) and iteroparous (offspring are produced in groups such as litters). They engage in internal reproduction in which sperm from the male fertilizes the egg within the female. It is thought that scalloped hammerheads breed every other year. The breeding season for northern Australian scalloped hammerheads occurs from February to March. The gestation period ranges from eight to 12 months. The number of offspring ranges from 12 to 41. Females reach sexual maturity at 15 to 17 years at around two meters in length. Males reach sexual maturity in as few as six years at 1.5 meters in length. [Source: Erick Ruiz and Sierra Trujillo, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Scalloped hammerheads are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. Mating behavior in scalloped hammerheads has been observed. According to Animal Diversity Web: Sexually mature males migrate to deeper waters in search of females. Since schools are formed primarily of females, male sharks will enter and swim in an S shape, signaling the desire to mate. Larger and more sexually mature females tend to be located in the center of the schools, pushing smaller females to the outside. When a male locates a receptive female, he bites her pectoral fin and secures himself. During mating, he curls his tail around her body to align their genitalia and inserts one of his claspers (modified anal fins) into her urogenital opening to deposit sperm. Because scalloped hammerheads are negatively buoyant, the mating pair sinks while copulation occurs.

During the pre-birth stage provisioning and protecting is done by females. As in other viviparous species, female scalloped hammerheads provide nutrition and protection to their internally developing young. Fertilized eggs develop into embryos that are nourished by a yolk-sac placenta attached to either of the female's two uteruses. There is no parental care after birth. Pups measuring 38 to 45 centimeters (1.2 to 1.5 feet) are born live. Immediately after birth, they must find their own food. They usually live in large schools until adulthood.

Humans, Scalloped Hammerhead and Conservation

Humans utilize scalloped hammerheads for food, drug research, education. and leather. Their body parts are sources of valuable materials and medicine. Humans harvest their fins for shark fin soup. Large hammerhead sharks are considered dangerous to humans, however, there have been no confirmed attacks on humans by scalloped hammerheads

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists them as “Endangered”. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) places them in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Protected Status: The species is protected by Endangered Species Act (ESA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife) in the U.S., which list it as Endangered in the Eastern Pacific and Eastern Atlantic and Threatened in the Central and Southwest Atlantic and Indo-West Pacific Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) Annex III throughout the wider Caribbean Region. [Source: NOAA]

Scalloped hammerheads are vulnerable to illegal fishing and bycatch during all stages of their lives. In 2007, surveys in the northwest Atlantic documented a 98 percent decline from historical estimates, while a 90 percent decline in population abundance was noted in the southwest Atlantic. The sharks have traditionally been important fishing fish in Mexico. They are fished both commercially and recreationally there and elsewhere. Their typically is not consumed as it contains high concentrations of urea. Oil is obtained from the liver. Their jaws and teeth are also sold as marine curios.[Source: Erick Ruiz and Sierra Trujillo, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) has banned the retention of hammerhead sharks caught while tuna fishing. The U.S. passed the Shark Conservation Act of 2010 to prevent finning (cutting the fins off sharks and throwing their bodies back in the water in U.S. waters.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023