Home | Category: Oceans and Sea Life / Physical Oceanography

SURFACE CURRENTS AND DEEP OCEAN CURRENTS

The two main types of ocean currents are surface currents and deep ocean currents, which dovetail with warm currents, which carry warm water from the equator toward the poles, and cold currents, which carry cold water from the poles toward the equator.

Surface Currents are found in the upper 400 meters of the ocean and are primarily driven by global wind systems. They are responsible for the horizontal movement of water across the ocean's surface. Examples include currents driven by local wind patterns like rip currents, longshore currents, and tidal currents. Surface currents drive about 10 percent of the ocean's water,

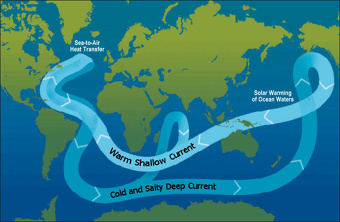

Deep Ocean Currents are driven by differences in water density, which are caused by variations in temperature and salinity. They form a large-scale, global circulation system known as the thermohaline circulation or the global conveyor belt. Deep ocean currents are responsible for movements in about 90 percent of the ocean's water.

Related Articles:

OCEANOGRAPHY AND STUDYING THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

PHYSICS OF THE OCEAN: PRESSURE, SOUND AND LIGHT ioa.factsanddetails.com

TEMPERATURE IN THE OCEAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

WAVES IN THE OCEAN: TYPES, CAUSES, AND EFFORTS TO DESCRIBE, PREDICT AND MEASURE THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

MAJOR OCEAN CURRENTS: THE GULF STREAM AND DEEP SEA, POLAR AND EQUATORIAL CURRENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN TIDES: TYPES, TERMS, FORCES, MEASUREMENTS AND PREDICTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEANS, WINDS AND WEATHER ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEANS: THEIR HISTORY, WATER, LAYERS AND DEPTH ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEAS AND OCEANS: DEFINITIONS, FEATURES AND THE MAIN ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

PHYSICAL FEATURES OF THE OCEAN FLOOR: TRENCHES, VENTS, MOUNTAINS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ISLANDS: TYPES, HOW THEY FORM, FEATURES AND NATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

LARGE WAVES: ROUGE WAVES, METEOTSUNAMIS AND THE BIGGEST WAVES EVER ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ocean Currents: Physical Drivers in a Changing World” by Robert Marsh, Erik van Sebille Amazon.com

“Ocean Currents and Their Effects on the Global Climate System” by Alexander Moreau (2025) Amazon.com

The “Great Ocean Conveyor: Discovering the Trigger for Abrupt Climate Change”

by Wally Broecker Amazon.com

“Gulf Stream Chronicles: A Naturalist Explores Life in an Ocean River” by David S. Lee and Leo Schleicher (Illustrator) Amazon.com

“The Gulf Stream: Encounters With the Blue God” by William MacLeish(1989) Amazon.com

“Ocean Circulation” Open University(2001) Amazon.com

“Adrift: The Curious Tale of the Lego Lost at Sea” by Tracey Williams (2022) Amazon.com

“Waves, Tides and Shallow-Water Processes” Open University(1989) Amazon.com

“Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean” by Jonathan White Amazon.com

“The Wave: In Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks, and Giants of the Ocean” by Susan Casey (2010) Amazon.com

“Waves in Oceanic and Coastal Waters” by Leo H. Holthuijsen (2007) Amazon.com

“Descriptive Physical Oceanography” by Lynne Talley (2017) Amazon.com

“Essentials of Oceanography” by Alam Trujillo and Harold Thurman Amazon.com

“The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works” by Helen Czerski, explains how the ocean influences our world and how it functions. Amazon.com

“How the Ocean Works: An Introduction to Oceanography” by Mark Denny (2008) Amazon.com

“The Science of the Ocean: The Secrets of the Seas Revealed” by DK (2020) Amazon.com

“Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics: Fundamentals and Large-Scale Circulation” by Geoffrey K. Vallis (2006) Amazon.com

“The Unnatural History of the Sea” by Callum Roberts (Island Press (2009) Amazon.com

“Ocean: The World's Last Wilderness Revealed” by Robert Dinwiddie , Philip Eales, et al. (2008) Amazon.com

“Blue Hope: Exploring and Caring for Earth's Magnificent Ocean” by Sylvia Earle (2014) Amazon.com

“National Geographic Ocean: A Global Odyssey” by Sylvia Earle (2021) Amazon.com

Eddies

An eddy is a circular current of water. The ocean is a huge body of water that is constantly in motion. General patterns of ocean flow are called currents. Sometimes theses currents can pinch off sections and create circular currents of water called an eddy. NASA satellite images show eddies and small currents responsible for the swirling pattern of phytoplankton blooms. [Source: NOAA]

You may have seen an eddy if you've ever gone canoeing and you see a small whirlpool of water while you paddle through the water. The swirling motion of eddies in the ocean cause nutrients that are normally found in colder, deeper waters to come to the surface.

Significant eddies are assigned names similar to hurricanes. In the U.S., an oceanographic company called Horizon Marine assigns names to each eddy as they occur. The names follow chronologically along with the alphabet and are decided upon by staff at Horizon Marine. The staff try to think of creative ways to assign names. For example, an eddy that formed in the Gulf of Mexico in June 2010 is named Eddy Franklin after Ben Franklin, as he was known to have done research on the Gulf Stream.

Old Sow Whirlpool and the Bay of Fundy

Old Sow is the name of the Western Hemisphere's largest whirlpool. While the turbulent water of Old Sow can be dangerous to small-craft mariners, its swirling motion has a positive environmental effect. It causes nutrients and tiny sea creatures normally found in the bay’s colder, deeper waters to rise to the surface. This process, called upwelling, ensures good eating for the resident fish and seabirds.

When the tide comes in from the Bay of Fundy, located off the Atlantic Coast between the State of Maine and the Province of New Brunswick, a tremendous amount of ocean water, called a current, flows swiftly into a confined area called the Western Passage before emptying upriver into Passamaquoddy Bay. After making a sharp right turn to the north and traversing a deep trench, flowing past an underwater mountain, and encountering several countercurrents, a portion of the current "pinches off" to form the huge circular current called Old Sow, and, often, several smaller ones, nicknamed “piglets.” Circular currents of all sizes are commonly known as whirlpools, vortexes, eddies, and gyres.

Old Sow varies in size but has been measured at more than 250 feet in diameter, about the length of a soccer field. While the turbulent water can be dangerous to small-craft mariners — some of whom have barely escaped a 12-foot drop into the Sow’s gaping maw — its swirling motion has a positive environmental effect. It causes nutrients and tiny sea creatures normally found in the bay’s colder, deeper waters to rise to the surface. This process, called upwelling, ensures good eating for the resident fish and seabirds. So why is the whirlpool called "Old Sow?" According to folklore, the name refers to the "grunting" noise — which sounds like hungry pigs slurping up their slop — made by the giant churning gyre. "Sow" may also be a mispronunciation of the word "sough" (pronounced suff), which means "sucking noise" or "drain."

Turbidity Currents

Global Ocean Conveyor Belt

A turbidity current is a rapid, downhill flow of water caused by increased density due to high amounts of sediment. Turbidity currents can be caused by earthquakes, collapsing slopes, and other geological disturbances. Once set in motion, the turbid water rushes downward and can change the physical shape of the seafloor. [Source: NOAA]

Turbidity is a measure of the level of particles such as sediment, plankton, or organic by-products, in a body of water. As the turbidity of water increases, it becomes denser and less clear due to a higher concentration of these light-blocking particles.

Turbidity currents can be set into motion when mud and sand on the continental shelf are loosened by earthquakes, collapsing slopes, and other geological disturbances. The turbid water then rushes downward like an avalanche, picking up sediment and increasing in speed as it flows.

Turbidity currents can change the physical shape of the seafloor by eroding large areas and creating underwater canyons. These currents also deposit huge amounts of sediment wherever they flow, usually in a gradient or fan pattern, with the largest particles at the bottom and the smallest ones on top.

NOAA scientists use current meters attached with turbidity sensors to gather data near underwater volcanoes and other highly active geological sites. Also, satellite imagery is used to observe turbidity by measuring the amount of light that is reflected by a section of water.

Geostrophic Currents and the Rubber Duckie Spill

A geostrophic current is an oceanic current in which the pressure gradient force is balanced by the Coriolis effect. The direction of geostrophic flow is parallel to the isobars, with the high pressure to the right of the flow in the Northern Hemisphere, and the high pressure to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. [Source: Wikipedia]

Away from the surface and seafloor Ekman layers, and over horizontal distances of tens of kilometers and timescales of days or more, horizontal pressure gradients in the ocean almost perfectly balance the Coriolis force created by moving water. This state is called geostrophic balance. Vertically, the dominant forces are the weight of the overlying water and the vertical pressure gradient, which balance each other to within a few parts per million. As a result, pressure at any depth is determined almost entirely by the weight of the water above it. [Source: Robert Stewart, “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”, Texas A&M University, 2008]

Horizontally, the pressure gradient and Coriolis force dominate, balancing to within a few parts per thousand over large distances. If the ocean had uniform density, then surfaces of equal pressure would remain parallel to the sea surface, and geostrophic currents would not vary with depth. Density that varies only with depth (but not horizontally) produces the same result. In both cases, the relative geostrophic flow is zero, and hydrographic data cannot reveal currents. This is known as barotropic flow.

When density varies laterally, constant-pressure and constant-density (isopycnal) surfaces tilt, creating baroclinic flow. In these cases, strong currents tend to run parallel to temperature or density fronts. The fronts themselves may remain stationary even while fast currents flow along them, so tracking the movement of small embedded eddies is essential for understanding the true motion of the water.

A famous real-world example involves the accidental release of 29,000 floating bath toys — including rubber ducks — from a container ship on January 10, 1992, near 44.7°N, 178.1°E. Their drift paths over months and even years provided valuable clues about ocean currents and large-scale circulation patterns.

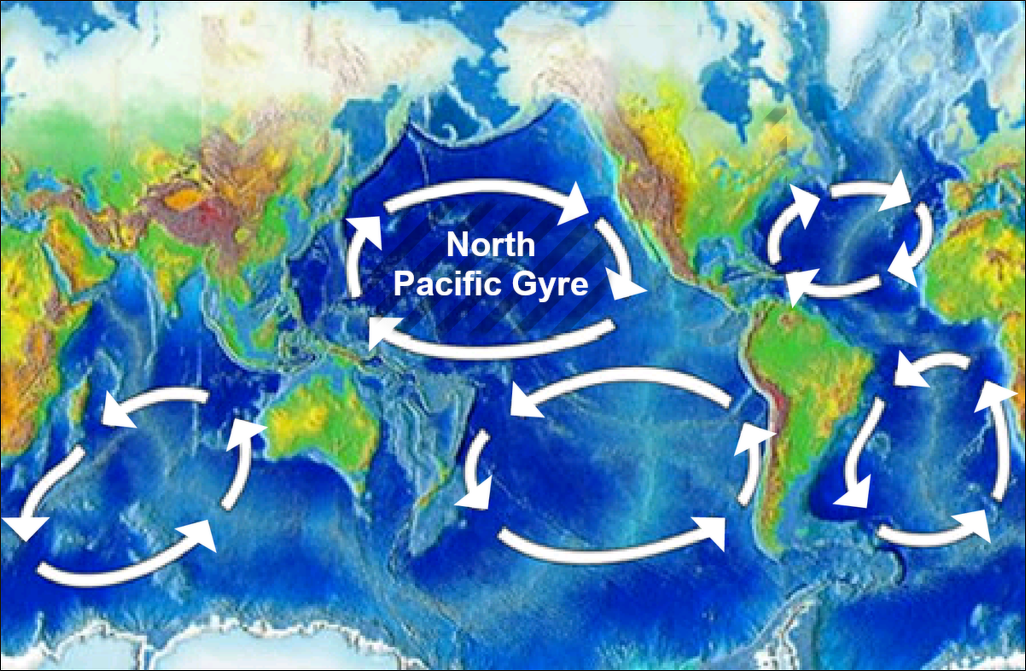

Gyres

A gyre is a large system of rotating ocean currents. There are five major gyres, which are large systems of rotating ocean currents. The ocean churns up various types of currents. Together, these larger and more permanent currents make up the systems of currents known as gyres. [Source: NOAA]

Wind, tides, and differences in temperature and salinity drive ocean currents. The ocean churns up different types of currents, such as eddies, whirlpools, or deep ocean currents. Larger, sustained currents — the Gulf Stream, for example — go by proper names. Taken together, these larger and more permanent currents make up the systems of currents known as gyres.

The five major gyres are: 1) the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre; 2) the South Pacific Subtropical Gyre; 3) the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre, 4) the South Atlantic Subtropical Gyre, and 5) the Indian Ocean Subtropical Gyre. In some instances, the term “gyre” is used to refer to the collections of plastic waste and other debris found in higher concentrations in certain parts of the ocean. While this use of "gyre" is increasingly common, the term traditionally refers simply to large, rotating ocean currents.

Upwelling

Winds blowing across the ocean surface push water away. Water then rises up from beneath the surface to replace the water that was pushed away. This process is known as “upwelling.” Upwelling occurs in the open ocean and along coastlines. The reverse process, called “downwelling,” also occurs when wind causes surface water to build up along a coastline and the surface water eventually sinks toward the bottom.

Upwelling brings deep, cold, often nutrient-rich water to the surface that “wells up” from below. There are five major coastal currents affiliated with strong upwelling zones, the California Current, the Humboldt Current off Peru, the Canary Current, the Benguela Current off Namimbia, and the Somali Current. Robert Stewart wrote in the “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”: Because steady winds blowing on the sea surface produce an Ekman layer that transports water at right angles to the wind direction, any spatial variability of the wind, or winds blowing along some coasts, can lead to upwelling. [Source: Robert Stewart, “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”, Texas A&M University, 2008]

Upwelling is important because: 1) it enhances biological productivity, which feeds fisheries; 2) cold upwelled water alters local weather. Weather onshore of regions of upwelling tend to have fog, low stratus clouds, a stable stratified atmosphere, little convection, and little rain. 3) Spatial variability of transports in the open ocean leads to upwelling and downwelling, which leads to redistribution of mass in the ocean, which leads to wind-driven geostrophic currents via Ekman pumping.

Water that rises to the surface as a result of upwelling is typically colder and is rich in nutrients. These nutrients “fertilize” surface waters, meaning that these surface waters often have high biological productivity. Therefore, good fishing grounds typically are found where upwelling is common.

To see how winds lead to coastal upwelling, consider north winds blowing parallel to the California Coast. The winds produce a mass transport away from the shore everywhere along the shore. The water pushed offshore can be replaced only by water from below the Ekman layer. This is upwelling. Because the upwelled water is cold, the upwelling leads to a region of cold water at the surface along the coast.

Upwelled water is colder than water normally found on the surface, and it is richer in nutrients. The nutrients fertilize phytoplankton in the mixed layer, which are eaten by zooplankton, which are eaten by small fish, which are eaten by larger fish and so on. As a result, upwelling regions are productive waters supporting the world’s major fisheries. The important regions are offshore of Peru, California, Somalia, Morocco, and Namibia.

Ekman transport and spatial variability of winds over distances of hundreds of kilometers and days leads to convergence and divergence of the transport and. A) Winds blowing toward the equator along west coasts of continents produces upwelling along the coast. This leads to cold, productive waters within about 100 kilometers of the shore. B) Upwelled water along west coasts of continents modifies the weather along the west coasts.

Upwelling Causes Millions of Fish to Leap Onto Beaches in the Philippines

In January 2024, a huge mass of sardines — likely in the millions — washed ashore on an island in the Philippines, leaving the coastline coated in a shimmering layer of tiny silver fish. Local scientists said that upwelling was the likely cause. The stranding began in the early morning along the shores of Maasim in Sarangani province, on the southern end of Mindanao. Photos and videos taken overnight show dense waves of sardines piling onto beaches or thrashing in the surf as more fish were pushed ashore. [Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, January 10, 2024]

By sunrise, residents had begun gathering the fish. On one beach, more than 100 people each collected 44 to 66 pounds (20 to 30 kilograms) of sardines, while one family amassed more than half a ton, according to The Nation. Much of the catch will be eaten or sold. Some locals saw the mass stranding as a good omen for the new year, while others feared it signaled an impending disaster.

Cirilo Aquadera Lagnason Jr., a researcher with the Protected Area Management Office of Sarangani Bay who witnessed the beaching, told Live Science that upwelling — a surge of nutrient-rich deep water rising toward the surface — can trigger huge plankton blooms. Sardines feed on plankton and may have followed the food into shallow water, where they became disoriented and easily stranded. He noted that similar events have occurred elsewhere in the Philippines. Most of the fish were juveniles, which may have made the schools more prone to confusion, he added.

Zenaida A. Dangkalan, a local fisheries officer, said other factors may also have contributed: unusually high sardine numbers, changes in water temperature or salinity, shifting predators, or even coastal light pollution.

Rip Currents

Rip currents are powerful, narrow channels of fast-moving water that are prevalent along the East, Gulf, and West coasts of the U.S., as well as along the shores of the Great Lakes. Moving at speeds of up to eight feet per second, rip currents can move faster than an Olympic swimmer. Panicked swimmers often try to counter a rip current by swimming straight back to shore — putting themselves at risk of drowning because of fatigue. Rip currents account for more than 80 percent of rescues performed by surf beach lifeguards. It is estimated that 100 people are killed by rip currents each year. If caught in one, don't fight it! Swim parallel to the shore and swim back to land at an angle. Always remember to swim at beaches with lifeguards. [Source: NOAA]

Rip currents are channeled currents of water flowing away from shore that quickly pull swimmers out to sea. They are created after a waves crash on the shore, then are funnelled through a break in the sand bar or another land formation. Rip currents are different from rip tides. They can be very strong and often occur when breaking waves push water up the beach face. This piled-up water must escape back out to the sea as water seeks its own level.

Rip currents typically extend from the shoreline, through the surf zone, and past the line of breaking waves. The best way to stay safe is to recognize the danger of rip currents. According to Surfer Today: Typically the return flow (backwash) is relatively uniform along the beach, so rip currents aren't present. A rip current can form if there's an area where the water can flow back out to the ocean easily - for instance, a break in the sand bar. Rip currents are generally only tens of feet in width, but there may be several at a given time spaced widely along the shore. [Source: Surfer Today]

See Separate Article:BEACH SAFETY, DANGERS AND HAZARDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, NOAA

Text Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025