Home | Category: Toothed Whales (Orcas, Sperm and Beaked Whales)

BELUGA WHALE CONSERVATION

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Near Threatened, They have been listed as Critically Endangered in the past. These whales have been placed in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. |=|

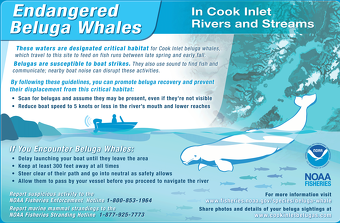

There are an estimated 200,000 beluga whales worldwide which is not bad but certain populations are suffering. The US Fish and Wildlife Service federal list lists a small beluga stock — 375 whales in Cook Inlet, Alaska — as Endangered. All beluga whale populations are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. NOAA Fisheries has designated the Cook Inlet beluga whale population in Alaska and the Sakhalin Bay-Nikolaya Bay-Amur River stock off the coast of Russia as depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. [Source: NOAA]

Overall the numbers beluga whale numbers in Alaska and Canada are relatively healthy but they have dropped substantially in Russia and Greenland. Of all seven extant Canadian beluga populations, those inhabiting eastern Hudson Bay, Ungava Bay, and the St. Lawrence River are listed as endangered.

Related Articles:

BELUGA WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BELUGA WHALES AND HUMANS: MILITARY USES, A SPY? TALKING NOC ioa.factsanddetails.com

NARWHALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

NARWHALS, HUMANS, CONSERVATION: USES, HUNTING, CLIMATE CHANGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

TOOTHED WHALES (ORCAS, SPERM AND BEAKED WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com;

TOOTHED WHALES: SWIMMING, ECHOLOCATION AND MELON-HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com;

WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF WHALES: ORIGIN, EVOLUTION, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WHALE BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

Threats to Beluga Whales

Threats to beluga whales include ocean noise, strandings, food limitations, pollution (such as, heavy metals, chemicals, trash), shipping, extreme weather events, subsistence harvesting, natural predators (polar bears and killer whales), contamination of rivers (as with polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) which bioaccumulate up the food chain), climate change, infectious diseases, habitat degradation, harassment, interactions with commercial and recreational fisheries, oil and gas exploration, and other types of human disturbance such as underwater noise. The threat of capturing beluga whales for the aquarium trade remains. Humans also pose a threat to belugas through the expansion of communities along the coast that affect beluga feeding areas and migration patterns. The Cook Inlet population faces additional threats because of its proximity to the most densely populated area of Alaska (Anchorage) during the summer season. [Source: NOAA]

Habitat Degradation: Beluga whales are susceptible to habitat destruction and degradation. This can range from physical barriers that limit their access to important migration, breeding, feeding, or calving areas, to activities that destroy or degrade their habitats. Physical barriers may include shoreline and offshore development (oil and gas exploration, dredging, pile driving) and increased boat traffic. Contaminant releases may also degrade habitat.

Contaminants enter ocean waters from many sources, including oil and gas development, wastewater discharges, urban runoff, and other industrial processes. Once in the environment, these substances move up the food chain and accumulate in predators at the top of the food chain such as beluga whales. Because of their long lifespan and blubber stores, belugas accumulate these contaminants in their bodies, threatening their immune and reproductive systems.

Food Limitations: Overfishing and habitat changes can decrease the amount of food available to beluga whales. Without enough prey, they might experience decreased reproductive rates and increased mortality rates. Understanding the potential for food limitations to hinder population recovery is especially important for Cook Inlet beluga whales because they live in an area with high human activity.

Strandings occur when marine mammals become "beached" or stuck in shallow water. The cause of most stranding cases is unknown. Belugas may strand when molting (to avoid predation or other threats, such as noise and vessel traffic), when chasing prey, or when suffering from injuries or disease. Unlike other whales and dolphins, healthy belugas that live-strand are usually able to refloat and swim to deeper water during the next high tide. Unfortunately, belugas have died after stranding on their sides and inhaling muddy water. Larger belugas with compromised immune systems also may not survive stranding through a tidal cycle.

Ocean Noise: Underwater noise pollution interrupts the normal behavior of beluga whales, which rely on sound to communicate and echolocate. If loud enough, noise can cause permanent or temporary hearing loss. This is of particular concern for the Cook Inlet population, which inhabits an area with high vessel traffic, oil and gas exploration and development, dredging and pile-driving, military operations, and other noise-making anthropogenic (human-caused) activities.

Beluga Hunting

Commercial and sport hunting once threatened beluga whale populations. These activities are now banned, though some groups in Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Russia still hunt beluga whales for subsistence — defined here as the practice of hunting marine mammals for food, clothing, shelter, heating, and other uses necessary for preserving the livelihood of Native communities. Beluga subsistence harvest in the Cook Inlet of south-central Alaska are now regulated because of the lack of recovery in the area. Alaska Natives last hunted Cook Inlet beluga whales in 2005.[Source: NOAA]

Because belugas like to hang around the coast, it is possible to coral them in shallow water and herd them towards the shore. On a beluga whale hunt in northern Greenland, Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Several Niaqornat men who'd been out hunting belugas before the storm were stranded a few hundred miles away, but no one in town expressed concern.[Source: Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, May 2009]

The Sunday before I left Greenland, the stranded beluga hunters chugged back to Niaqornat in their boat. Just before darkness fell, people made their way down to the water. Bundled-up babies were lifted high overhead for a better view; older children were ruddy with excitement, because beluga mattak (fermented meat and blubber) is second only to the narwhal's as winter fare. The dogs yelped as the yellow boat, laminated with ice, pulled into the dock.

Bashful before so many eyes but stealing proud looks at their wives, the hunters spread tarps and then tossed out sections of beluga spine and huge, quivering organs, which landed with a slap on the dock. Last of all came the beluga mattak, folded in bags, like fluffy white towels. The dismembered whales were loaded into wheelbarrows and spirited away; there would be great feasting that night on beluga, which, like narwhal meat, is nearly black because of all the oxygen-binding myoglobin in the muscle. It would be boiled and served with generous crescents of blubber.

Captive Belugas

Shimane Aquarium AQUAS in Hamada, Japan, is famous for its beluga whales who do bubble ring tricks. The belugas blow air bubbles out of their mouths, creating what are often called "bubble rings of happiness" or "angel halos". The belugas create bubble rings by blowing air through their blowholes and then releasing it through their mouths. The bubble ring trick was developed by aquarium staff who noticed one beluga, Aliya, could squirt water and then trained her to blow air bubbles, which she seemed to enjoy. In addition to the bubble rings, the belugas also perform other tricks, such as the "Magic Ring of Happiness". The bubble ring performance is a major draw for visitors, with many specifically coming to see the belugas' unique trick. These bubble rings have become a popular attraction, with some believing they bring good luck or happiness to those who see them. AQUAS is the only aquarium in western Japan that keeps beluga whales.

On his experience with belugas at SeaWorld in San Diego and encounter with Ruby, the former military beluga kept at SeaWorld, Charles Siebert wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “The challenge of confining such long-lived creatures accustomed to roaming as much as 100 miles of icy ocean a day in extensive, multi-tiered social groups is daunting. Recent advancements on such fronts as water circulation, tank hygiene and nutrition have vastly increased life expectancy for beluga whales and yet most captive belugas rarely live past their teens or early 20s, typically succumbing to one of various fungal and bacterial infections such as pneumonia or meningitis. Or to a noxious surfeit of human noise. [Source: Charles Siebert, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2014]

“Once inside SeaWorld San Diego’s front gates, one is immediately subsumed by sound. Calypso Muzak clashes with rock ’n’ roll and these with the blaring triumphal trumpets and 60-foot-boat-slide screams from the popular water ride, Journey to Atlantis. Loudspeakers issue repeated reminders of the fast dwindling seats for upcoming shows at the Shamu and Dolphin stadiums. It’s impossible to imagine what all that sounds like to whales: creatures who can hear one another across oceans. “Only four belugas were visible in the tank as I approached, circling in the same direction before breaching, and then doing that same circuit, over and over again: a classic pathology of life in captivity or, per the SeaWorld training manual, “controlled environment.”

“Down one level, there was a rare, uncontested spot at the exhibit’s underwater viewing glass. Allua, Ferdinand and Nanuq — I’d gotten their names from the guide — all swam by, as did Pearl, Ruby’s 4-year-old calf by Nanuq. But there was still no sign of Ruby. And then, as though she’d been waiting for her own uncontested moment at the glass, a wide-smiling gray-spotted melon appeared before me. She just hovered there, her body straight upright, her head — belugas are unusual among whales in the number of unfused neck vertebrae, permitting a high degree of vertical neck movement — assuming a strangely dazed and asking tilt, like that slow-blinking alien standing on the open spaceship ramp at the end of Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

““Belugas in captivity actually mute their senses,” Samantha Berg, a trainer at SeaWorld from 1990 to 1993, told me recently. “It’s so loud around them, and they don’t need to use their echolocation because they’ve been in the same tank every day and already know all the boundaries of their world. When I was working with them, my impression was that they weren’t all there, as though they were deeply bored, disinterested. They were like people with post-traumatic stress disorder. I don’t know what belugas are like in the wild, but it was almost as though they were staring at me through a veil. Like they weren’t really home.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025