Home | Category: Toothed Whales (Orcas, Sperm and Beaked Whales)

BELUGA WHALES AND HUMANS

Beluga whales have traditionally played an important role in the survival of Canadian and Alaskan Inuits, also known as Inuvialuits, as well as indigenous groups in Russia. For centuries, the belugas have been a main food source for these small communities and their blubber has also been used for oil. These whales also bring ecotourists interested in whale watching because of the belugas large social gatherings, creating new jobs and allowing growth in the community.

The native peoples of North America and Russia have hunted belugas for many centuries. They were also hunted by non-natives during the 19th century and part of the 20th century. Hunting of belugas is not controlled by the International Whaling Commission, and each country has developed its own regulations in different years. Currently, some Inuit in Canada and Greenland, Alaska Native groups and Russians are allowed to hunt belugas for consumption as well as for sale, as aboriginal whaling is excluded from the International Whaling Commission 1986 moratorium on hunting. [Source: Wikipedia]

Belugas are one of the most commonly kept cetaceans in captivity and are housed in aquariums, dolphinariums and wildlife parks in North America, Europe and Asia. They are considered charismatic because of their docile demeanour and characteristic smile, communicative nature,and supple, graceful movement. Belugas were still caught in the Russian Far East, Glazov in 2010s and sold on to oceanariums, where they were trained for public performances, and research institutes in Russia and elsewhere. The practice received a lot of bad press in 2019 with the revelation of a so-called “whale jail” in Russia’s Far East, where 11 orcas and 87 belugas were held captive in appalling conditions before being sold. Some newspapers called it a “concentration camp” for whales. Russian president, Vladimir Putin, personally intervened in the situation. [Source: Andrew Roth, The Guardian, May 10, 2019]

Related Articles:

BELUGA WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BELUGA WHALE CONSERVATION: THREATS, HUNTING, CAPTIVITY ioa.factsanddetails.com

NARWHALS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

NARWHALS, HUMANS, CONSERVATION: USES, HUNTING, CLIMATE CHANGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

TOOTHED WHALES (ORCAS, SPERM AND BEAKED WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com;

TOOTHED WHALES: SWIMMING, ECHOLOCATION AND MELON-HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com;

WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF WHALES: ORIGIN, EVOLUTION, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WHALE BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

Cape Beluzhiy: Beluga Whale Watching Site

Cape Beluzhiy — near Bolshoy Solovetsky, Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea about 1,000 kilometers north of St. Petersburg) is one of the best places in the world to see white beluga whales. This cape is one of the rare places on the Earth the whales come close to the shore. In other places, you need to go to the open sea, which does not allow approaching the belugas too closely, because these animals are very timid.

At low tide, the belugas swim near Cape Beluzhiy twice a day. But this unique act of nature can be seen during a very short period: from the middle of June until the middle of August, and only in when the sea is relatively calm. At this time, the belugas are breeding and training their young in the shallow water.

A tower was constructed here for watching belugas by scientists of the Institute of Oceanology RAS, which have been studying are carrying out since 1994. You can get to the cape by the road leading to Sekirnaya Mountain or the old monastery road along the seashore. Theoretically, you can get to the cape by boat, but it is not recommended because it would disturb the belugas. Still many people do take boats. One person wrote in Trip Advisor: “Took around 30 minutes one way to the cape where is at the White Sea. We successfully saw some white whales near our boat. The boat ride was pretty windy and cold. Have to be well prepared even in the summer.”

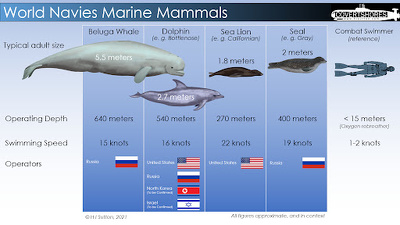

Beluga Whales in the U.S. and Russian Military

The U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammal Program as it’s called today was established in the 1950s when Navy researchers attempted to improve torpedo design by studying dolphins. In the 1960s, the U.S. Navy Marine Mammal Program in San Diego switched from studying dolphin’s swimming and acoustic ability to investigating their potential as vehicles of war. The Navy also studied sea lions, beluga whales and other marine animals. [Source: Tony Perry, Los Angeles Times, April 2007; Dwight Holing, Discover, October 1988]

One of the early missions of he Marine Mammal Program was to defend ports and the important ships berthed there, especially nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and nuclear-powered ballistic-missile submarines, both of which are key to U.S. deterrence and power-projection. The Marine Mammal Program’s collection of animals peaked in the 1980s. As of 2007, there were 74 dolphins at the U.S. Navy facility at Point Loma, California, which also has 25 California sea lions. The Navy’s sole beluga whale was kept nearby at SeaWorld. [Source: Stavros Atlamazoglou, Business Insider, February 2, 2023; Maddie Bender, Daily Beast, August 18, 2022]]

Charles Siebert wrote in Smithsonian Magazine:“Since the early 1960s the United States had been deploying marine mammals, beginning with dolphins, for tasks including mine detection and recovery of test torpedoes. By the mid-1970s, the locus of the naval cold war had shifted to the Arctic, where the latest Soviet submarines were secreting themselves under the ice cap, an environment off-limits to animals including dolphins and sea lions used in the Navy Marine Mammal Program (NMMP). Experiments commenced on weaponry that could function in such extreme conditions. The Navy needed marine mammals with built-in sonar, capable of locating and retrieving sunken experimental torpedoes in the frigid waters and low visibility of the Arctic.[Source: Charles Siebert, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2014]

In the 1990s the mission of beluga whales was changed to a new operation, dubbed Deep Hear. It was developed to test the potential effects on marine mammals of a new type of low-frequency active sonar (LFAS), which has since been cited by more than 100 scientists as the cause of massive whale strandings. The noise often induces entire pods to surface so rapidly in an attempt to escape it, they die of a condition to which scientists had assumed whales to be immune: the bends.

The Soviets and Russians also used beluga whales for military purposes. There were reports of plans to use belugas to defend the waters off Sochi during the 2014 Olympics, but it is unclear whether they were used or not. It is believed that belugas were deployed by Russia in the war with Ukraine in the Black Sea to defend the Russian fleet in the Crimean peninsula. Marine animals in the Russian programs, including dolphins and beluga whales, are trained to find combat swimmers and detect mines, [Source: Isobel van Hagen, Business Insider, June 17, 2023]

Catching and Utilizing Military Beluga Whales

Charles Siebert wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “In August 1977, with Canadian government consent, Sam Ridgway, a Texas-born veterinarian and a co-founder of NMMP, dispatched a team to the northern coast of Manitoba. There, the Navy would procure the first belugas for a new Arctic initiative, known as “Cold Ops.”

“Belugas make for obliging quarry, their affable, curious natures often leading them directly up to divers and boats. As for the vessel Ridgway had deployed that summer 37 years ago, it also contained two Inuit hunters hired to expedite the recruitment process. When a beluga approached their boat, one hunter would jump on the whale’s back and slip a lasso around its neck, like a high plains mustang. The other would then slide a floating stretcher under the whale and lead it ashore. Once there it was placed in a leak-proof crate containing a few centimeters of water and loaded onto a transport jet for immediate transfer to a netted underwater enclosure at the Navy’s Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center, off Point Loma, California. [Source: Charles Siebert, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2014]

“Six belugas were caught between 1977 and 1980. The new Cold Ops recruits proved not only to be remarkable divers, ultimately reaching preset platforms at depths of over 2,000 feet, but pinpointing retrievers as well. Belugas evolved their precisely honed echolocation powers in order to both navigate the Arctic’s dark waters and to find available pockets of breathing air between the ocean surface and the underside of the ice cap. Pinging on mud-embedded test torpedoes proved, by comparison, an easily dispatched task. They would also learn to wield a mouthpiece with a special “grabber assembly” for retrieval of the torpedoes from the ocean floor.

Sam Ridgway wa sthe head of the U.S. Navy’s Marine Mammal Program involving beluga whales. There are images of deep-diving training tests off San Clemente Island, 70 miles west of the Southern California coast show two belugas — Noc and Muk Tuk — dutifully reporting to the side of the Navy training vessel, receiving both spoken and hand-signaled instructions, and then disappearing under the water surface. The most critical factor for Ridgway and his team was that the new Cold Ops trainees willingly returned to their trainers. The darker undercurrent of such fidelity, of course, was that the animals had nobody else to turn to. During training sessions at a special weapons testing range, a jointly operated Canadian-U.S. facility in Nanoose Bay off the east coast of Vancouver Island, a group of animal rights activists managed to infiltrate the base there and release Noc and Muk Tuk from their enclosure.

Both whales headed at first for open water, but Noc returned of his own volition a short time later. Muk Tuk swam some 14 miles south along the coast before willingly following a pursuing Cold Ops training vessel back to base. “They come to think of us as family,” Ridgway said. “And that’s the reason they stay with us. We have no way of completely controlling them, and yet they do their job and come back. They kind of view themselves as part of a team. Or at least we view them as seeing themselves as part of a team.”

Mystery Beluga Found of Off Norway — a Russian Spy?

In the spring of 2019, a beluga whale spotted off the coast of Norway was believed to be trained by the Russian navy. Fishermen reported a beluga whale wearing strange harnesses, which may have held cameras, harassing their boats, pulling on straps and ropes. This led to allegations the whale was a Russian spy; other said it was more likely a therapist whale from an animal park.

Andrew Roth wrote in The Guardian: When Morten Vikeby saw reports that a “spy whale” from Russia had been found off the Norwegian coast, he immediately phoned his old fishery newspaper Fiskeribladet with a tip. The amiable beluga reminded him not of a spy, he said, but of a “therapy whale” he’d seen a decade ago at a diving centre in northern Russia. That whale, named Semyon, lived in a watery enclosure in Russia’s Murmansk region, and sometimes entertained tour groups of children with mental disabilities.“Maybe it wasn’t the same whale but it acted the same way,” said Vikeby, a former Norwegian consul to the city of Murmansk, in a telephone interview. “The whale has been accused of espionage. I see it as my big purpose to defend him.”[Source: Andrew Roth, The Guardian, May 10, 2019]

The tame beluga found off Norway’s Ingoya island has become a local celebrity. Locals have christened him “Hvaldimir”, a portmanteau of the Norwegian word for whale, hval, and the popular Russian name, Vladimir. A regular in the sea by the harbour city of Hammerfest, he even retrieved a woman’s iPhone after she dropped it in the water earlier this week. But the harness he was wearing when he was found, bearing a buckle stamped “Equipment St Petersburg”, has dogged his reputation, fuelling speculation that he escaped a military training programme in Russia’s north. After all, who else would have put a harness on a whale, perhaps to hold a camera, and then not publicly admit it had gone missing?

Dmitry Glazov, a Russian scientist and deputy head of the beluga white whale programme, said that near Murmansk alone there were “three organisations, not necessarily military, some civilian, that train marine mammals, including belugas, for various tasks: retrieving objects, or finding divers who have had problems, like equipment malfunctions”. But he said the presence of a harness alone would not confirm that Hvaldimir has any ties to the Russian military. “These kinds of buckles are sold all across Russia,” he said.

The likelihood that Hvaldimir is the same whale that Vikeby saw in Russia in 2008 is a long shot. “For the last two and a half years, there haven’t been any whales here,” said Mikhail Safonov, the head of the Arctic Circle dive centre. The whales belonged to a separate organisation called the Belomorsk Ecological Centre, Safonov said, adding that he believed they had sold the last whale to the St Petersburg Oceanarium in 2016.

Noc — the Beluga Whale That Tried to Talk to Humans?

While captive in a Navy program, a beluga whale named Noc (pronounced no-see) began to mimic human speech. Charles Siebert wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: The youngest of the Cold Op’s recruits, Noc lived virtually his entire life in captivity, working side by side with human trainers. He ended up being deployed for two top-secret Navy surveillance and retrieval programs, with another beluga named Muk Tuk, before succumbing to meningitis in 1999 at the age of 23 while still in the Navy’s care. [Source: Charles Siebert, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2014]

Noc was suddenly re-emerged in the form of a 20-odd-second recording, included as a mere supplement to a research paper by Ridgway, “Spontaneous Human Speech Mimicry by a Cetacean,” in the October 23, 2012, edition of the journal Current Biology. “Within days Noc’s voice was burbling from computers around the globe. He sounds, on first hearing, at least, less like a person talking than a delirious drunk humming an atonal tune through a tissue-covered comb.

“Ridgway said he didn’t remember there being anything particularly strange or different about Noc over the course of the first seven years preceding his sudden speech episodes. He did describe him as being somewhat lazy and unfocused at first during open-sea training sessions, often delighting in purposely delaying the proceedings through an avoidance behavior known as “mucking” (diving down to suck invertebrates from the seafloor). Sometimes he’d just bow out completely, swimming the 70 miles back to his enclosure in San Diego Bay. “I do remember Noc would often kind of sit back and watch Muk Tuk,” Ridgway offered at one point. “And then he’d get all jealous when Muk Tuk did her job and got her reward. Suddenly he’d want to have his turn. But he had to wait for Muk Tuk to finish first.”

Noc Starts Talking Like a Human

Charles Siebert wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “In May 1984 Ridgway and his fellow Cold Ops personnel began hearing strange noises emanating from the whales’ enclosure — sounds they would liken in the Current Biology paper to “two people conversing...just out of range for our understanding.” “My office was on the end of a pier in San Diego Bay,” Ridgway said. “Noc had his home enclosure next to the pier. I would hear these ‘talking sounds’ late in the day as I headed down the pier toward the parking lot. I assumed these talking sounds resulted from a conversation on one of the two adjacent piers about 150 feet away from me.” [Source: Charles Siebert, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2014]

“Also that May, two Navy divers were making underwater repairs on the Point Loma whale enclosures. Throughout these sessions they would talk with their onshore dive supervisor through an audible underwater communications device known as a “wet phone.” In the middle of that day’s outing, one of the divers, a Navy veteran in his late 30s, Miles Bragget, abruptly surfaced and asked a puzzled supervisor: “Who told me to get out?” Informed of the incident later, Ridgway and his team decided to start keeping a closer eye and ear on their beluga recruits.

““After a set period of time,” Ridgway explained, “or after the divers completed a task, the supervisor would typically order them out. It was also not uncommon for Noc to be in the vicinity when the underwater communications systems were being used. But Bragget had come up at a point when the supervisor had said nothing. It turns out that Bragget heard Noc. The ‘out’ he thought he’d heard, we realized, had come from Noc. He repeated the word several times.”

““I didn’t observe Miles’ initial interaction,” Michelle Jeffries, one of Noc’s early trainers said of Bragget, who died in 1990, “but I was at the facility that day. I remember when Miles got out of the water he was sure the dive monitor and the guys around the pens were kidding him when they said they did not call him out of the water. He thought they were pulling his leg. But we realized pretty quickly what was going on, maybe because of the way Noc reacted to the divers, watching them from his pen, following them, focusing on Miles in particular. Belugas are very aware of people and their actions, especially Noc, and Miles had a nice touch with Noc. He was a gentle man. And once we figured out that it was Noc, we were all excited, laughing, and, I think, completely humbled by this amazing animal.” Four years after Noc launched into his talking spree, he just as abruptly stopped, reverting in 1999 to “Beluga” for the rest of his days in captivity.

How Noc Talked

Charles Siebert wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Subsequent spectrum analysis of Noc’s utterances soon revealed just how skilled a speaker he was. The rhythm and amplitude of his vocal bursts and the intervals between them were found to pattern those of human speech. His fundamental frequencies, meanwhile, also matched those of humans, registering around 200 to 300 hertz, roughly the octave of middle C, and several octaves below the white whale’s usual sounds. Noc would even yield to the repeated insertion of a device known as a “rapid response pressure catheter” into the nasal cavities and air sacs beneath his blowhole. This allowed Ridgway to get a clearer understanding of just how Noc was accomplishing his bizarre vocal acrobatics. [Source: Charles Siebert, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2014]

“Belugas produce sounds by building up air pressure in the nasal cavities within their melon, the echolocation organ at the front of their heads, and then forcing the air through a set of “phonic lips” atop each cavity. The vibrations of the lips result in the whale’s typical repertoire of echolocation clicks, pulse bursts and chirp-like whistles and squeaks. Noc, Ridgway discovered, was so over-inflating his nasal cavities during his mimicry episodes that his melon would visibly distend, seemingly to the point of bursting, and all to wrench his natural speech into the precise tenor and sonic topography of our own.

“Once Noc had been identified as the source of Bragget’s perceived evacuation order, Ridgway and his Marine Mammal Program cohorts began recording their precocious white whale’s by-then irrepressible speech episodes. He spoke both underwater and in open air, either spontaneously or on command, and yet only when around humans or off by himself, never with his fellow whales. Before long, Jeffries told me, she had only to point at Noc and say the word “out,” and he would start rambling away, sometimes as much as 30 or more unbroken seconds of his surreal juice-harp oratory.

“There had been numerous claims in the past about the naturally vociferous beluga talking in our language as well. Until Noc, however, no one had ever had an opportunity to do the repeated observations, acoustic recordings and audio analysis required to verify what people had long believed they were hearing.

Did Noc Really Talk

““We do not claim that our whale was a good mimic compared to such well-known mimics as parrots or myna birds,” Ridgway’s Current Biology paper concludes. “However, the sonic behavior we observed is an example of vocal learning by the white whale. It seems likely that Noc’s close association with humans played a role in how often he employed his human voice, as well as in its quality.”

Charles Siebert wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: ““Episodes of animal mimicry have long been dismissed as “mere parroting,” a disparagement that recent research on the intelligence of parrots and a number of species, including whales, reveals to be rather narrow-minded on our part. Through a process known as “parallel evolution,” whales — some 55 million years our seniors — first developed a brain comparable to our far more recently evolved one. It’s a brain that has structures involved in functions such as self-recognition, memory, advanced socialization and language, enabling a fluency in some forever other and yet deeply parallel parlance. [Source: Charles Siebert, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2014]

““Vocal imitation, vocal learning, is a very sophisticated cognitive process,” says Lori Marino, a senior lecturer in the department of psychology at Emory University who specializes in cetacean intelligence and brain evolution. “For an animal to imitate another species takes a level of self-awareness, a level of understanding of their body and your body and the acoustics of it. Manipulating one’s vocal tract to produce a desired effect is very, very sophisticated.”

““Yes, their brains are different,” Marino adds. “The cortex is completely different. And that’s what makes them so fascinating. The old line was that their brains are just these big masses of tissue for hearing, just giant audio receivers. But there’s so much integrative cortical tissue there that does more than just receive. It brings things together, synthesizes and does complex processing in ways we obviously don’t understand yet. But it’s not as though we have this huge complex whale brain and no commensurately complex behavior. They are individuals. They have lives to lead and social relationships. They have families, and they have really good memories. And that’s something places like SeaWorld don’t want to touch because then you start getting into issues that people can really relate to.”

Why Noc Talked

Michelle Jeffries was a co-author of the Current Biology paper on Noc. Charles Siebert wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Jeffries began working with the Cold Ops belugas in 1981. Noc was six at that point and had, it seemed, evolved by then into the consummate team player. ““Noc really warmed my heart,” Jeffries said. “He was very easygoing. He wanted people’s attention. He wanted you to stay around and interact with him and rub him. He didn’t try to bullshit you like some of the dolphins did. He was just glad for your time, and he was very patient. Plus being the younger one, he was a little bit more reactive, eager. Noc was the kid who was willing to try. I think that was part of the thing behind him mimicking speech. He liked watching people. He liked being around people. The connection. He wanted to make a connection. I think that was his thing. He liked the interface.” [Source: Charles Siebert, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2014]

Diana Reiss, a professor of biopsychology at Hunter College, has spent much of her career studying cetacean cognition and communication, mostly in dolphins. “Noc had other female belugas around, but he was the only male, like the odd guy out,” Reiss told me. “And the question often asked: Is this an attempt to communicate or is this just mindless mimicry? I suspect that for these animals there is something very reinforcing about what they’re doing. They’re not doing it for food. But if they can get the attention of those around them by sounding like them, it may give them the social reinforcement they need. It has some social function.”

“For 16 years, Toni Frohoff, a marine mammal behaviorist based in Santa Barbara, California, has studied a subset of the beluga population in the St. Lawrence estuary known as “solitary sociables”, whales separated from their families, usually because of a mother’s death at the hands of hunters or from effects of pollution, who end up gravitating to people for companionship.

“Most orca and dolphin vocalizations, Frohoff has found, occur underwater. But solitary sociable wild belugas rise up out of the water when they speak to us, purposefully orienting their bodies and voices in our direction. “Wild, free-ranging belugas,” says Frohoff, “do not initiate this kind of vocal behavior, no matter how many boats and people may be around. So there’s an obvious analogy between these geographically isolated and socially deprived animals in the wild and captive belugas like Noc. We’re talking about social deprivation here, a lack of any reasonable normal interaction with his own kind. So what may seem amusing to us, or an attempt to communicate with us, is in a sadder vein a coping mechanism for him, both an outgrowth and avoidance of his own boredom.”

“Noc’s speech episodes are perhaps best thought of in that way now, the years of his outbursts having coincided — as they do in most documented instances of animal mimicry — with the period of adolescence. It’s as though he was a deeply bored teenager at once mocking us and sounding a desperate plea for help. The extraterrestrial intelligences we humans have so long sought contact with turn out to have been right here beside us all along. It’s only fitting then, somehow, that all we have left now of Noc is his human voice.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025