Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish / Economics, Fishing and Agriculture / Government, Infrastructure, Economics / Government, Infrastructure, Economics / Government, Infrastructure, Economics / Government, Infrastructure, Economics / Government, Infrastructure, Economics

SPECIES OF TUNA

There are 15 species of tuna. Across five genera. "True" tunas are that belong to the genus Thunnus. It was long reckoned that there were seven Thunnus species, and that Atlantic bluefin tuna and Pacific bluefin tuna were subspecies of a single species. In 1999, it established that based on both molecular and morphological considerations, they are in fact distinct species.

The genus Thunnus is further classified into two subgenera: Thunnus (Thunnus) (the bluefin group), and Thunnus (Neothunnus) (the yellowfin group). Several are important commercially. Among these are yellowfin, skipjack, bigeye, albacore, and Atlantic, Pacific, and southern bluefin— some of most valuable wild fishes. Most canned tuna and the grilled tuna and tuna salads served in restaurants uses skipjack and yellowfin tuna. Tuna served at sushi restaurants, especially the better ones, is typically bluefin tuna. The fifteen tuna species are:

Thunnus (Thunnus) – the bluefin group

Common name — Scientific name — Maximum length — Common length — Maximum weight — Maximum age — IUCN status

1) Pacific bluefin tuna — T. orientalis (Temminck & Schlegel, 1844) — 3.0 meters (9.8 feet) — 2.0 meters (6.6 feet) — 450 kilograms (990 pounds) — 15–26 years — Near Threatened

2) Atlantic bluefin tuna — T. thynnus (Linnaeus, 1758) — 4.6 meters (15 feet) — 2.0 meters (6.6 feet) — 684 kilograms (1,508 pounds) — 35–50 years — Least Concern

3) Southern bluefin tuna — T. maccoyii (Castelnau, 1872) — 2.45 meters (8.0 feet) — 1.6 meters (5.2 feet) — 260 kilograms (570 pounds) — 20–40 years — Endangered

4) Albacore tuna — T. alalunga (Bonnaterre, 1788) — 1.4 meters (4.6 feet) — 1.0 meters (3.3 feet) — 60.3 kilograms (133 pounds) — 9–13 years — Least Concern

5) Bigeye tuna — T. obesus (Lowe, 1839) — 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) — 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) — 210 kilograms (460 pounds) — 5–16 years — Vulnerable

[Source: Wikipedia, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species]

Thunnus (Neothunnus) – the yellowfin group

Common name — Scientific name — Maximum length — Common length — Maximum weight — Maximum age — IUCN status

6) Yellowfin tuna — T. albacares (Bonnaterre, 1788) — 2.4 meters (7.9 feet) — 1.5 meters (4.9 feet) — 200 kilograms (440 pounds) — 5–9 years — Least Concern

7) Blackfin tuna — T. atlanticus (Lesson, 1831) — 1.1 meters (3.6 feet) — 0.7 meters (2.3 feet) — 22.4 kilograms (49 pounds) — Least concern

8) Longtail tuna (northern bluefin tuna, tongol tuna) — T. tonggol (Bleeker, 1851) — 1.45 meters (4.8 feet) — 0.7 meters (2.3 feet) — 35.9 kilograms (79 pounds) — 18 years — Data deficient

The Thunnini tribe also includes seven additional species of tuna across four genera. They are:

Common name — Scientific name — Maximumlength — Commonlength — Maximum weight — Maximum age — IUCN status

9) Skipjack tuna — Katsuwonus pelamis (Linnaeus, 1758) — 1.1 meters (3.6 feet) — 0.8 meters (2.6 feet) — 34.5 kilograms (76 pounds) — 6–12 years — Least concern

10) Slender tuna — Allothunnus fallai (Serventy, 1948) — 1.05 meters (3.4 feet) — 0.86 meters (2.8 feet) — 13.7 kilograms (30 pounds) — — Least concern

11) Bullet tuna — Auxis rochei (Risso, 1810) — 0.5 meters (1.6 feet) — 0.35 meters (1.1 feet) — 1.8 kilograms (4.0 pounds) — 5 years — Least concern

12) Frigate tuna — Auxis thazard (Lacépède, 1800) — 0.65 meters (2.1 feet) — 0.35 meters (1.1 feet) — 1.7 kilograms (3.7 pounds) — 5 years — Least concern

13) Mackerel tuna (Kawakawa) — Euthynnus affinis (Cantor, 1849) — 1.0 meters (3.3 feet) — 0.6 meters (2.0 feet) — 13.6 kilograms (30 pounds) — 6 years — Least concern

14) Little tunny — Euthynnus alletteratus (Rafinesque, 1810) — 1.2 meters (3.9 feet) — 0.8 meters (2.6 feet) — 16.5 kilograms (36 pounds) — 10 years — Least concern

15) Black skipjack tuna — Euthynnus lineatus (Kishinouye, 1920) — 0.84 meters (2.8 feet) — 0.6 meters (2.0 feet) — 11.8 kilograms (26 pounds) — Least concern

Top Tuna Commercial Fish Species

Global Wild Fish Catch Ranking — Common name(s) — Scientific name — Harvest in tonnes (1000 kilograms)

3) Skipjack tuna — Katsuwonus pelamis — 2,795,339 tonnes

6) Yellowfin tuna — Thunnus albacares — 1,352,204 tonnes

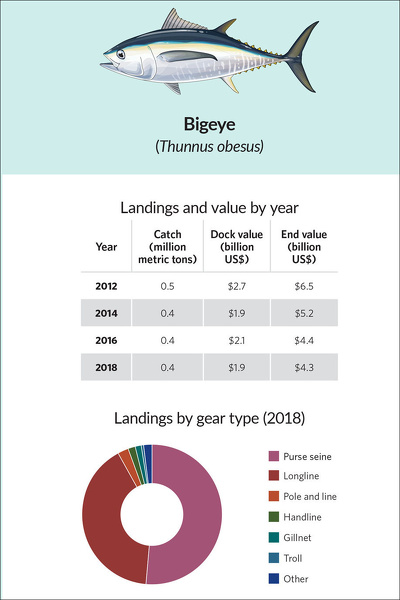

20) Bigeye tuna — Thunnus obesus — 450,546 tonnes

34) Little tuna (Kawakawa, mackerel tuna) — Euthynnus affinis — 328,927 tonnes

43) Albacore — Thunnus alalunga — 256,082 tonnes

48) Longtail tuna — Thunnus tonggol — 234,427 tonnes

[Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2012; Wikipedia]

Websites and Resources: “Netting Billions 2020: A Global Tuna Valuation, Pew Charitable Trusts”, October 6, 2020 pewtrusts.org; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

See Separate Articles: TUNA: CHARACTERISTICS, SPEED, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; TUNA FISHING, FOOD, PROCESSING AND SANDWICHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Bluefin Tuna

Bluefin tuna Bluefin tuna are one the most valuable fish in the sea. Prized for making sushi and sashimi in Japan, they appeared in the caves of ancient people, were placed on coins by the ancient Romans, painted by Salvador Dali and described by fishmongers in Tokyo as Catherine Zeta-Jones of the sea. At Nishinomiya Shrine in Nishinomiyama Hyogo Prefecture in Japan people press coins onto a frozen tuna and pray to Ebisui, the deity of wealth and commerce.

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker, “The Atlantic bluefin tuna is shaped like a child’s idea of a fish, with a pointy snout, two dorsal fins, and a rounded belly that gradually tapers toward the back. It is gunmetal blue on top, and silvery on the underside, and its tail looks like a sickle. The Atlantic bluefin is one of the fastest swimmers in the sea, reaching speeds of fifty-five miles an hour. They are voracious carnivores — they feed on squid, crustaceans, and other fish — and can grow to be fifteen feet long. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, August 2, 2010]

Bluefin tuna live in saltwater or marine environments usually in the open ocean far from land at depths of zero to 550 meters (1804 feet). The generally inhabit the epipelagic (open ocean) region, but occasionally come close to shore. They have tolerance to a wide temperature range (2° to 30°C, 36° to 86°F) and thus can inhabit waters at a variety of depths and a variety of latitudes. [Source: Matt Zbroinski, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

See Separate Articles: BLUEFIN TUNA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, HUNTING AND MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA SPECIES: ONE IN THE PACIFIC, ONE IN THE SOUTH, TWO IN THE ATLANTIC ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA COMMERCIAL FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA AND SUSHI ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA FISH FARMING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; LOW BLUEFIN TUNA NUMBERS: OVERFISHING, ORGANIZATIONS, QUOTAS AND PROTESTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Yellowfin Tuna

Yellowfin tuna is one of the main components of canned tuna and one of the most heavily fished of all fishes. Often marketed as ahi, it is popular in sushi and s widely consumed in Japan in sashimi and sushi. In the late 2000s, around 20,000 to 38,000 tons of the annual catch of 100,000 to 150,000 tons of the fish caught in central and western Pacific is consumed in Japan. Yellowfin tuna are found in huge schools near the surface that are scooped up with purse seine nets and caught with hooks and lines. Because overfishing of the fish is regarded as a serious problem in some places fishing experts have called for a 30 percent reduction of the yellowfin tuna catch,

Also known as kihada, Yellowfin tuna (Scientific name: Thunnus albacares) are torpedo-shaped. They are metallic dark blue on the back and upper sides and change from yellow to silver and white on the belly. True to their name, their dorsal and anal fins and finlets are bright yellow. An adult yellowfin tuna can be distinguished from other tunas by its long, bright-yellow dorsal fin and a yellow stripe down its side. [Source: NOAA]

Yellowfin tuna grow fast, up to two meters (6 feet) long and 181 kilograms (400 pounds) and have a somewhat short life span of 6 to 7 years. Most yellowfin tuna are able to reproduce when they reach age two. Adult yellowfin tuna feed near the top of the food chain on fish, squid, and crustaceans. Fish, seabirds, dolphins, and other animals prey on larval and juvenile tuna. Marine mammals, billfish, and sharks feed on adult tuna..

See Separate Article YELLOWFIN TUNA: FISHING, RECORDS AND A MISSING FISHERMAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

Skipjack Tuna

Commonly used in canned tuna, skipjack tuna reach lengths of two and three feet. They live in tropical and subtropical waters. One of the most heavily fished of all fishes, they are found in huge schools near the surface that are scooped up with purse seine nets and caught with hooks and lines. Skipjack tuna stock are still healthy. Skipjack tuna closely resemble bonitos. Skipjack tuna are often called a bonitos, especially in Japanese contexts. Bonitos technically are different group of tuna-like fish but are not tuna (Bonitos, See Below). [Source: NOAA, Wikipedia]

Skipjack tuna (Scientific name: Katsuwonus pelamis) grow fast, like other tropical tunas, up to nearly 1.3 meters 4 feet and more than 30 interesting (70 pounds.) They have a short life span compared to other temperate tunas, around 8 to 12 years. They are opportunistic feeders, preying on a variety of fish, crustaceans, cephalopods, mollusks, and sometimes other skipjack tunas. Large pelagic fishes such as billfish, sharks, and other large tunas prey on skipjack tuna..

Also known as ocean bonito, lesser tuna, aku and katsuo, skipjack tuna do not have scales except on the corselet and the lateral line. The corselet is a band of large, thick scales forming a circle around the body behind the head and extending backward along the lateral line. The lateral line is a faint line running lengthwise down each side of the fish. Their back is dark purplish-blue, and their lower sides and belly are silvery with four to six conspicuous dark bands that run from behind the head to the tail, which may look like a series of dark blotches.

See Separate Article SKIPJACK TUNA AND BONITO ioa.factsanddetails.com

Albacore Tuna

Albacore Tuna (Scientific name: Thunnus alalunga) is regarded as one of the healthiest fish to eat if you ignore the possible mercury incursions, which are usually infinitesimally small. Albacore has about three times as much omega 3 — the nutritious fatty oil — as skipjack or “light” tuna. With fresh tuna, the belly is fattier than the meat on either side. This means it is oilier and contains more omega 3s. . [Source: NOAA]

Also known as albacore, germon, longfinned tuna, albecor, ahipalaha, tombo, Albacore tuna have torpedo-shaped bodies, smooth skin, large eyes and streamlined fins. They are metallic, dark blue on the back, lighter blue laterally, with dusky to silvery white coloration along the sides of the belly. They have exceptionally long pectoral fins, which are at least half the length of their bodies. The edge of the tail fin is white.

Albacore tuna grow fast at first but more slowly with age, up to almost 36 kilograms 80 pounds and about 1.3 meters (four feet) long. They’re able to reproduce when they reach 5 to 6 years old, and they live for 10 to 12 years. North Pacific albacore spawn between March and July in tropical and subtropical waters of the Pacific. Females broadcast their eggs near the surface, where they’re fertilized. Depending on their size, females release between 800,000 and 2.6 million eggs every time they spawn.

Albacore can swim at speeds exceeding 50 miles per hour and cover vast areas during annual migrations. They have a highly evolved circulatory system that regulates their body temperature and increases muscle efficiency; a high metabolism; and high blood pressure, volume, and hemoglobin, all of which increase oxygen absorption. They lack the structures needed to pump oxygen-rich water over their gills so, in order to breathe, they must constantly swim with their mouths open.

Albacore are top carnivores, preying on schooling stocks such as sardine, anchovy, and squid. They eat an enormous amount of food to fuel their high metabolism, sometimes consuming as much as 25 percent of their own weight every day. Larger species of billfish, tuna, and sharks eat albacore..

Albacore Tuna Habitat and Migrations

Albacore tuna are found in tropical and warm temperate waters of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans. They are a highly migratory species, swimming long distances throughout the ocean. Temperature is a major factor in determining where Pacific albacore live. Juveniles are often found near oceanic fronts or temperate discontinuities. Adults are found in depths of at least 1,250 feet. They also explore deeper waters in search of prey..

Similarly sized albacore travel together in schools that can be up to 30 kilometers (19 miles) wide. North Pacific albacore, particularly juveniles (2 to 4 years old), typically begin their expansive migration in the spring and early summer in waters off Japan. They move into inshore waters off the U.S. Pacific coast by late summer, then spend late fall and winter in the western Pacific Ocean. The timing and distance of their migrations in a given year depend on oceanic conditions.

Less is known about the movements of albacore in the South Pacific Ocean — juveniles move southward from the tropics when they are about a foot long, and then eastward to about 130̊ West. When the fish are mature, they return to tropical and subtropical waters to spawn.

Albacore Tuna Fishing

According to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 256,082 tonnes (1000 kilograms) of albacore tuna was caught and landed in 2012. In 2020, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Pacific albacore tuna totaled approximately 7.2 million kilograms (16 million pounds) and were valued at more than $25 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. The majority of Pacific albacore tuna is landed in Washington and Oregon. Hawaii albacore is mostly sold fresh. There are also significant landings in American Samoa, averaging approximately 3 million pounds per year, most of which is canned locally. North Pacific albacore are a popular and important recreational species. Off the West Coast, commercial passenger fishing vessels are required to keep logbooks to document their catch. There are bag limits in U.S. federal and state waters.[Source: NOAA]

On the U.S. West Coast, commercial fishermen target the North Pacific stock primarily using troll and pole-and-line (bait boat) gear. In Hawaii, longline vessels harvest North Pacific albacore while targeting swordfish and other tunas. In American Samoa, longline vessels target the South Pacific stock. Bycatch in U.S. albacore fisheries is low. Based on limited observer data, troll and pole-and-line (bait boat) gears have insignificant levels of bycatch. Interactions with sea turtles can occur in longline fisheries, but extensive observer coverage in U.S. fisheries indicates these interactions are rare. U.S. longline fishermen are required to use specific tools and handling techniques to reduce the effects of bycatch. Several other management measures are in place, such as gear modifications and time-area closures, to limit and prevent interactions between longline gear and other species.

U.S. wild-caught Pacific albacore tuna is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations. There are above target population levels. The fishing rate is at recommended levels. Fishing gear used to catch albacore rarely contacts the seafloor so habitat impacts are minimal. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch. Population Status: There are two stocks of Pacific albacore tuna: the North Pacific stock and the South Pacific stock. According to the most recent stock assessments both are not overfished and not subject to overfishing (2020 and 2015 stock assessment).

Albacore Tuna Fishing Management

NOAA Fisheries and the Pacific Fishery Management Council manage the Pacific albacore tuna fishery on the West Coast. The species are managed under the Fishery Management Plan for U.S. West Coast Fisheries for Highly Migratory Species, which: 1) Requires commercial fishermen to obtain a permit from NOAA Fisheries and maintain logbooks documenting their catch; and 2) Restricts the use of longline gear in specific areas and times of the year, to minimize impacts on protected resources, including sea turtles, marine mammals, and seabirds.

NOAA Fisheries and Western Pacific Fishery Management Council manage this fishery in the Pacific Islands. The species are managed under the Fishery Ecosystem Plan for the Pelagic Fisheries of the Western Pacific. There, fishermen are required to have permits and to record their catch in logbooks. There are gear restrictions, monitoring, and operational requirements to minimize bycatch. A limit on the number of permits for Hawaii and American Samoa longline fisheries controls participation in the fishery.

Longline fishing prohibited in areas around the Main Hawaiian Islands, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa to protect endangered Hawaiian monk seals, and reduce potential gear conflicts and localized stock depletion (when a large quantity of fish are removed from an area). These areas are enforced through NOAA Fisheries’ vessel monitoring system program. Longline boats must be equipped with a satellite transponder that provides real-time position updates and tracks vessel movements.

Hawaii-based and American Samoa–based longline vessels must carry onboard observers when requested by NOAA Fisheries, in part to record any interactions with sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals. Mandatory annual protected species workshops for all longline vessel owners and operators are required. Management of highly migratory species, like Pacific albacore tuna, is complicated because the species migrate thousands of miles across international boundaries and are fished by many nations.

Effective conservation and management of this resource requires international cooperation as well as strong domestic management. Two international organizations, the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), manage this fishery. These Commissions rely on the scientific advice of their staff and the analyses of the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific (ISC) to develop and adopt international resolutions for conservation and management measures. Working with the U.S. Department of State, NOAA Fisheries domestically implements these conservation and management measures.

Bigeye Tuna

Bigeye tuna is widely sold as supermarket sashimi in Japan, where it is popular because of its relatively cheap price and a taste that is similar to bluefin tuna. Declining supplies of bluefin tuna have increased demand for bigeye tuna.

Also known as tuna, big eye, bigeye, ‘ahi, mabachi and ahi-b, bigeye tuna (Scientific name: Thunnus obesus) are dark metallic blue and yellow on the back and upper sides and shiny white on the lower sides and belly. The first fin on their back is deep yellow, the second dorsal and anal fins are pale yellow, and the finlets are bright yellow with black edges. The tail fin is dark gray while other fins are more tan. [Source: NOAA]

Bigeye and yellowfin tuna look fairly similar. In fact, it’s hard to distinguish the two species without experience. Among other characteristics, the bigeye’s eyes are larger than the yellowfin’s and their finlets have black edges. Bigeye tuna feed near the top of the food chain, preying on fish, crustaceans, and squid. They are prey for many top predators, including sharks, billfish, larger tunas, and toothed whales..

Bigeye tuna grow fast and can reach about two meters (6.5 feet) in length in the Pacific Ocean and 1.7 meters (5.5 feet) in the Atlantic Ocean. In the Atlantic they can live up to nine years and are able to reproduce when they are 3.5 years old. In the Pacific they live 7 to 8 years and are able to reproduce when they are 3 years old.

In the Pacific bigeye tuna spawn throughout the year in tropical waters and seasonally in cooler waters. They’re able to spawn almost daily, releasing millions of eggs each time. Eggs are found in the top layer of the ocean, buoyed at the surface by a single oil droplet until they hatch. In the Atlantic bigeye tuna spawn throughout the year but most often in the summer. They usually spawn two or more times a year. Females release between 3 million and 6 million eggs each time they spawn.

Bigeye Tuna Habitat and Where They Are Found

Bigeye tuna are found throughout the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, including the waters around the U.S. Pacific Islands and off southern California. In the western Atlantic, they can be found from Southern Nova Scotia to Brazil.

Bigeye tuna favor water temperatures between 13° and 29° C (55° and 84° F). They often swim in schools and live at or near the surface but dive into deeper waters (to about 800 feet, deeper than other tropical tunas) during the day. Larvae are found in tropical waters, and as juvenile fish grow larger they tend to move into temperate waters.

Bigeye tuna are highly migratory and travel long distances throughout the ocean. Juvenile and small adult bigeye tuna school at the surface, sometimes with skipjack and juvenile yellowfin tunas especially in warm waters. Schools of bigeye tuna may associate with floating objects or large, slow-moving marine animals such as whale sharks or manta rays. Bigeye tuna also group together near seamounts and submarine ridges..

Bigeye Tuna Fishing

According to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 450,546 tonnes (1000 kilograms) of bigeye tuna was caught and landed in 2012. As of about that time, Japan and Taiwan had the largest bigeye fishing fleets, Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and Maldives have large artisan fleets and provide processing for large vessels

The majority of U.S.-caught bigeye tuna comes from Hawaii, although a substantial amount is also harvested by U.S. purse seine vessels and landed in American Samoa or other countries for canning. In 2020, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Pacific bigeye tuna totaled 7.6 million kilograms (16.7 million pounds) and were valued at $56 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. The U.S. bigeye tuna fishery in the Atlantic Ocean is much smaller. In 2020, U.S. commercial landings of Atlantic bigeye tuna totaled 450,000 kilograms (one million pounds), and were valued at more than $4.8 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database.

tail of a bigeye tuna As for recreational fishermen, off California, anglers must be licensed and daily bag limits are in place. Recreational charter boats must keep logbooks of their catch. There are no federal regulations for recreational fishing off Hawaii and U.S. Pacific Island territories, but local rules may apply. [Source: NOAA]

There are two stocks of Pacific bigeye tuna: the Western and Central Pacific stock and the Eastern Pacific stock. According to the most recent stock assessments: Both are not overfished and not subject to overfishing (2020 stock assessment). Since hitting a low in 2004, the Eastern Pacific population has been increasing in abundance and is now above its target population level. The increase is partly due to international tuna conservation measures, which established time/area closures for the purse seine fleets and instituted catch quotas in the longline fleets. The Atlantic stock is significantly below target population level (See Bigeye Tuna Overfishing and Quotas Below) [Source: NOAA]

Bigeye Tuna Fishing in the Pacific Ocean

Fishermen based in Hawaii, American Samoa, and the U.S. Pacific Islands target Pacific bigeye tuna with hook-and-line, pelagic longline, or troll fishing gear U.S. commercial purse seine fishermen in the western and central Pacific also harvest bigeye tuna. The U.S. coastal purse seine fleet operating in the eastern Pacific Ocean typically fish off California for small pelagic species such as sardine and anchovy and sometimes catch bigeye tuna when warm water from the south brings bigeye tuna within their range.

Fishing gear used to catch Pacific bigeye tuna rarely contacts the seafloor so habitat impacts are minimal. Restrictions on the type of fishing gear that can be used, and prohibitions on fishing in certain areas, minimize impacts on protected species. Interactions with protected species such as sea turtles, marine mammals, and seabirds in these fisheries are rare and survival rates are estimated to be high for all gear types. Longline fishermen are trained in safe handling and release techniques for sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals, and they carry and use specific equipment for handling and releasing these animals.Scientists and managers continue to monitor bycatch in these fisheries through logbooks and fishery observer programs. Management measures are in place to minimize bycatch of juvenile Pacific bigeye tuna.

U.S. wild-caught Pacific bigeye tuna is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations. There are above target population level in the Eastern Pacific and near population level in the Western and Central Pacific but fishing rate promotes growth. The fishing rate is at recommended levels in the Western and Central Pacific and the Eastern Pacific. Fishing gear used to catch bigeye tuna rarely contacts the seafloor so habitat impacts are minimal. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.

Bigeye Tuna Fishing Management in the Pacific Ocean

NOAA Fisheries and the Pacific Fishery Management Council manage this fishery on the West Coast. The species are managed under the Fishery Management Plan for U.S. West Coast Fisheries for Highly Migratory Species. Fishermen are required to have permits and to record catch in logbooks. Gear restrictions and operational requirements are in place to minimize bycatch. Large purse seine vessels that fish for tuna in the eastern Pacific Ocean are required to have 100 percent observer coverage. All other commercial vessels based on the U.S. West Coast must carry an observer if requested by NOAA Fisheries. Longline fishing is prohibited within 200 miles of the U.S. West Coast. Annual training in safe handling and release techniques for protected species is required and all vessels must carry and use specific equipment for handling and releasing these animals.

Bigeye

NOAA Fisheries and Western Pacific Fishery Management Council manage this fishery in the Pacific Islands. The species are managed under the Fishery Ecosystem Plan for the Pelagic Fisheries of the Western Pacific: Fishermen are required to have permits and to record catch in logbooks. Gear restrictions and operational requirements are in place to minimize bycatch and potential gear conflicts among different fisheries. A limit on the number of permits for Hawaii and American Samoa longline fisheries controls participation in the fishery. Longline fishing is prohibited in some areas to protect endangered Hawaiian monk seals, reduce conflicts between fishermen, and prevent localized stock depletion (when a large number of fish are removed from an area). These areas are enforced through the NOAA Fisheries vessel monitoring system program (longline boats must be equipped with a satellite transponder that provides real-time position updates and tracks vessel movements). Hawaii-based and American Samoa–based longline vessels must carry onboard observers when requested by NOAA Fisheries, in part to record interactions with sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals. Annual training in safe handling and release techniques for protected species is required and all vessels must carry and use specific equipment for handling and releasing these animals.

Management of highly migratory species, like Pacific bigeye tuna, is complicated because the species migrate thousands of miles across international boundaries and are fished by many nations. Effective conservation and management of this resource requires international cooperation as well as strong domestic management. Two international organizations, the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), manage this fishery internationally. Working with the U.S. Department of State, NOAA Fisheries domestically implements the IATTC and WCPFC conservation and management measures.

Under the South Pacific Tuna Treaty, U.S. purse seine vessels operating throughout the western and central Pacific Ocean must be registered and are monitored through logbooks, cannery landing receipts, national surveillance activities, observers, and port sampling. Purse seiners in the eastern Pacific Ocean also operate under the International Dolphin Conservation Program, a multilateral agreement aimed at reducing and minimizing bycatch of dolphins and undersize tuna.

Bigeye Tuna Overfishing and Quotas

In December 2008, the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commissions (WCPFC) agreed to cut catches of bigeye tuna, in part of the Pacific Ocean by 10 percent in each of the next three years. Environmentalists criticized the decision for being too little too late. They wanted an immediate reduction of 30 percent. in June 2009, the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission agreed to cut quotas of bigeye tuna in the eastern Pacific Ocean by nine percent in 2011 from 2007 levels.

The Atlantic stock is significantly below target population level. According to the 2021 stock assessment, Atlantic bigeye tuna is overfished, but not subject to overfishing. The United States is working with other nations to develop an international rebuilding plan. The fishing rate is at recommended levels. Fishing gear used to catch bigeye tuna rarely contacts the seafloor so habitat impacts are minimal. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch. [Source: NOAA]

relative sizes

In 2011, International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) decided to retain the annual fishing quota for bigeye tuna at the current level until 2015, the Japanese Fisheries Agency said. Kyodo reported: The overall maximum catch will remain at 85,000 tons a year in the Atlantic Ocean, including 23,611 tons for Japan, as the ICCAT has concluded that stocks can be maintained at a certain level if catches are kept low, the agency said. [Source: Kyodo, November 21, 2011]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA, graphs and graphics from The Pew Charitable Trusts (“Netting Billions 2020: A Global Tuna Valuation, October 6, 2020 pewtrusts.org)

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023

_diagram_cropped.GIF)