Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish

DECLINES OF BLUE FIN TUNA

slicing up magaro at Tsukiji market in Tokyo By some estimates bluefin tuna stocks declined 80 percent between the 1950s and 2000. The number of mature Atlantic bluefin is thought to have dropped from 250,000 in 1970 to 100,000 in 2005. Greenpeace and other environmental organizations have become increasingly critical of the bluefin trade and many sushi restaurants in Europe don t serve the fish.

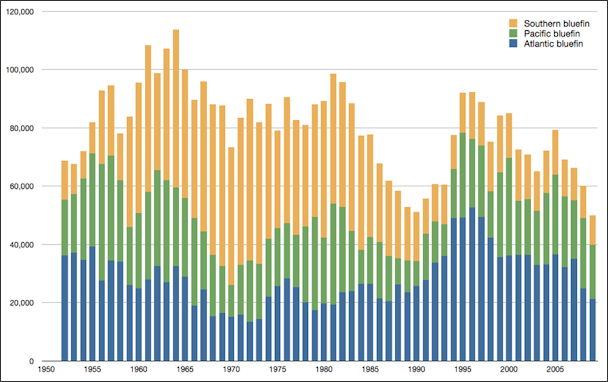

Catches of bluefin tuna declined 93 percent between 1963 and 2004. Bluefin tuna in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans are thought to be between 6 and 12 percent what the once were. Since 1950 more than 50 million tons of tuna and other top predators have been taken from the Pacific. Still breeding stocks of bluefin in the Pacific seem to holding their own but those in the Atlantic and the southern seas are not faring as well.

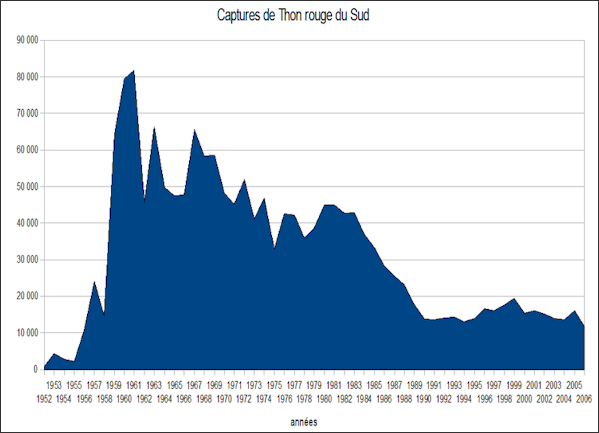

The total population of southern bluefish tuna is thought to be about 8 percent of what it was before industrialized fishing began to take off in the 1950s. The migration route of the fish are well known and fishermen have been exploiting them for decades. The fish only begin spawning after they reach the age of eight but most are caught before then, meaning the fish have not reproduced enough to keep its population going.

In his book “The Unnatural History of the Sea” Callum Roberts wrote: Today “there is probably only one bluefin tuna left for every forty present in 1940. “The last of these regal fish are today pursued more relentlessly that ever...The fish are now so valuable that it pays to employ planes and helicopters to scan the ocean, guiding boats in for the kill when the fish are spotted. This isn’t fishing any more — it is the extermination of a species.”

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists Pacific bluefin tuna as “Vulnerable”. The fish has no special status according to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The IUCN Red List vulnerable status means they are not Endangered yet, but without any protective measures, they will be. NOAA Fisheries states that these tuna are over-fished, and have proposed a harvest reduction to support sustainable fisheries.

Websites and Resources: “Netting Billions 2020: A Global Tuna Valuation, Pew Charitable Trusts”, October 6, 2020 pewtrusts.org; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

See Separate Articles: TUNA: CHARACTERISTICS, SPEED, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, HUNTING AND MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA SPECIES: ONE IN THE PACIFIC, ONE IN THE SOUTH, TWO IN THE ATLANTIC ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA COMMERCIAL FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA AND SUSHI ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA FISH FARMING ioa.factsanddetails.com

Causes of the Decline in Bluefin Tuna Numbers

Overfishing is main culprit in the decline of the bluefin tuna. Love of sushi, particularly in Japan, is blamed for the declining bluefin tuna stock. But is not the reason. Consumption of bluefin tuna is declining somewhat in Japan as prices go up but is on the rise in the United States and elsewhere. Pollution and global warming might also be factors in their decline.

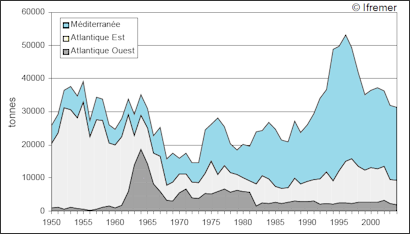

The decline in tuna numbers has been blamed in part on the use of roll-net equipped and purse seine fishing boats that scoop up large volumes of fish in one swoop. Declines in the Mediterranean have been blamed on fishing and the corralling of fish for “tuna farms.” Ecologist say that if a collapse of tuna stocks does occur it will grave consequence on the entire Mediterranean because it is one of the top predators and its loss would have a destabilizing effect on the entire ecosystem of the sea. Illegal fishing is another big problem. Small boats are not properly regulated. Renegade boats are know to fly the flags of countries with regulations, knowing they will not be noticed.

One of the problems with current fishing patterns, Catherine Kilduff, a staff attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity, told NPR is is that most — possibly more than 98 percent, she says — of the Pacific bluefin that are caught and processed are immature juveniles that have never reproduced. [Source: Alastair Bland, NPR.org, June 29, 2016]

In the old days there were so many frozen bluefin tuna at Tsukiji market's auction in Tokyo they had to be stacked on top of each other. That is no longer the case. One wholesale fish buyer told the Washington Post. “We were too loose in governing our own fishing. We now need a very rigid regimen to show the world we can control ourselves. Instead of eating tuna twice a week, the Japanese are going to have to settle for twice a month...We all have to share what we have got. If we do that. I don’t think they are going extinct.” As sources in the Atlantic and southern seas began to dry up Japanese began to look for new sources. They began turning to the Mediterranean in the 1990s, which at that time was still not strongly exploited.

Diminishing Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Stocks

tuna buyer in Greece In the mid 2000s, scientists said that the Atlantic bluefin tuna was in danger of becoming extinct unless drastic measures was taken soon. Between 1975 and 2005 one of the bluefin’s two main populations declined by 80 percent. Breeding stocks of bluefin in the Western Atlantic have been depleted by 80 percent to 90 percent. The breeding population in 1997 was estimated 40,000 adults down from 250,000 in 1977.

The estimated weight of “spawning stock biomass” of adult Western Atlantic bluefin tuna dropped from 49,482 metric tons in 1970 to 8,693 metric tons in 2007 according to ICCAT. the number of mature fishing caught off the East Coast of North America dropped 87 percent in 30 years. Fisherman there have only been able to catch 15 percent of the quotas between 2003 and 2007.

The estimated weight of “spawning stock biomass” of adult Eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna dropped from 250,412 metric tons in 1970 to 100,046 metric tons in 2007 according to ICCAT. Stocks that spend time in the Mediterranean are thought to be particularly in danger. Nets are turning up empty. In 2007 ships converged on an area off Libya thought to be one the last refuges for the fish.

Sergei Tudeal, a Spanish marine biologist, told National Geographic, “My big fear is that it may be too late. I have a very graphic image in my mind. It is of the migration of so many buffalo in the American West in the early 19th century. It was the same with the bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean, a migration of a massive number of animals, And now we are witnessing the same phenomenon happening to giant bluefin tuna that we saw happened with America’s buffalo. We are witnessing this, right now, right before out eyes, “

According to some studies, stocks are not suffering as much as previously thought. The population in the western Atlantic has been stable since 1988 and schools of 4,500-strong bluefin tuna are regularly spotted.

In April 2010, the BP’s Deepwater Horizon rig exploded, and oil began gushing into the Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf is one of only two known Atlantic-bluefin spawning sites, and April is the start of the spawning season. It is not known what effect the oil spill had on Atlantic bluefin tuna stocks.

Tuna Organizations

Five regional fishery control organizations control (or at least try to control) tuna fishing worldwide. The world’s five tuna Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) are: 1) ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas); 2) Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commissions (WCPFC ); 3) Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission; 4) Commission Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) ; 5) Indian Ocean Tuna Commission.

The international bluefin tuna fishery essentially manages itself, setting its own quotas each year, critic say. Members of the RFMOs typically come from within the fishing industry. Members of the world’s five RFMOs met in Kobe in January 2007. A14-point agreement hammered out created regulations to reign in illegal fishing, control growth of fleets and share data on stock assessments.A scheme for catch-tracking or catch documentation, which stipulates that fishing nations certify that tuna has been caught in accordance with regulations, was set up. The scheme requires the tagging of fish for easier tracking from ship to market. It was harder for the group to make decisions on quotas and quota reductions. All members agreed that cuts needed to be made by it was difficult for the five RFMOs to agree on which individual groups would have to make the greatest sacrifices.

The WCPFC is an international organization for managing marine resources, including tuna and bonito, in western and central Pacific zones, including the sea off Japanese shores. It was established in 2004, and member countries include Japan, Australia and the United States. The WCPCF has a committee of scientists that conducts research on fish populations and other conditions and issues recommendations. It also can adopt measures to protect marine resources at its annual general meetings of member countries.

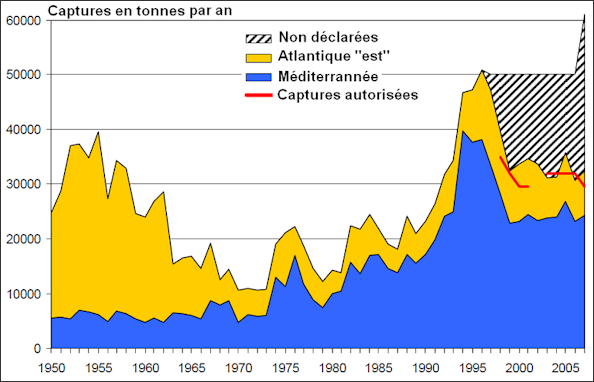

Bluefin tuna catches

ICCAT — an International Disgrace

ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas) is the global body in charge of setting the rules for tuna fishing. Environmentalists blame it for not doing more to help tuna by raising quotas, reducing fish catches and steeping up efforts to enforce the quotas and clamp down on illegally exceeding the quotas.

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker, “ICCAT” — pronounced “eye-cat” — is based in Madrid, and its members include the U.S., the European Union, Japan, Canada, and Brazil. In 2008, ICCAT scientists recommended that the bluefin catch in the eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean be limited to between eighty-five hundred and fifteen thousand tons. ICCAT instead adopted a quota of twenty-two thousand tons. That same year, a panel of independent reviewers, hired by the commission to assess its performance, observed that ICCAT “is widely regarded as an international disgrace.” (Carl Safina, the noted marine conservationist, has nicknamed the group the International Conspiracy to Catch All the Tunas.) [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, August 2, 2010]

Kenneth Brower wrote in National Geographic: ““For most of its history, ICCAT has ignored the advice of its scientific panel, the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS). For the eastern stock that breeds in the Mediterranean, the much larger population, ICCAT has routinely set quotas far higher than science recommends. In 2008 the SCRS issued its most alarming assessment yet on the status of the eastern stock. The actual catch, the scientists reported, was likely more than double the 28,500 metric tons of the allowable catch, and more than quadruple a level that was sustainable. They recommended closing the fishery through the main spawning period and reducing the allowable catch to 15,000 metric tons or less. ICCAT, as usual, ignored this plea. [Source: Kenneth Brower, National Geographic, March 2014]

“The same year, ICCAT commissioned an independent review of its policies. The review panel, composed of eminent fisheries managers and fisheries scientists from around the world, was not gentle. It found that ICCAT stewardship of the eastern stock was a “travesty of fisheries management.” The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the International Union for Conservation of Nature have chimed in with similar sentiments.

“In 2009 Monaco, in response to the decades of mismanagement, proposed that the Atlantic bluefin be listed on Appendix I of Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. Such a listing would have meant an international ban on trade in bluefin, and Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) delegates from fishing nations rallied to defeat the proposal. But ICCAT had its wake-up call. That same year, for the first time, it followed scientific advice in setting quotas for eastern bluefin. In 2011, to address illegal fishing, it began testing a system that would electronically track caught fish from ocean to market, and early in 2014 the system is to be fully implemented. In 2015 ICCAT is committed to revising its antiquated stock-assessment protocols.

“This is movement in the right direction, but ICCAT’s structure and governance remain unchanged, vulnerable to political pressure from fishing interests in its member states. Tuna science, always politicized, has recently become much more so. As it is no longer possible for ICCAT to simply ignore scientific advice, there is now an effort to massage the science. “There are inherent uncertainties about these stock assessments,” Amanda Nickson, director of global tuna conservation at the Pew Charitable Trusts, told me. “We’re seeing a mining of the areas of uncertainty to justify increases in quota.” Industry-funded biologists propose that there might be undiscovered spawning grounds for Atlantic bluefin. It is possible, of course, but there is no real evidence for the proposition. The idea seems awfully convenient for an agenda favoring business as usual.

global capture of bluefin tuna species from 1950

Quotas and Limits on Blue Fin Tuna Fishing

The global bluefin tuna catch was cut by 39 percent in 2010 from the previous year to 11,500 tons with Japan’s total catch reduced to 1,148 tons. In the 1960s, fishermen caught about 80,000 metric tons of bluefin tuna, most for canned food. Later Japanese, Australian and New Zealand operators are limited to about 12,000 tons a year. In 1995, European nations caught 39,331 metric tons of bluefin tuna while the United States, Japan and Canada caught 2,285 tons (in accordance with restrictions of 2,500 metric tons).

In December 2010, the 25-member Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission agrees to cut catches of bluefin tuna in 2011 and 2012 to below 2002-2004 levels, It was the first international agreement to bluefin tuna catches in the Pacific Ocean. The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission’s 25 members including Japan, China, Samoa, South Korea and the United States.

Officials with the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission have called for cuts in the catch of bluefin tuna, especially of young fish, because of stock declines since the mid 1990s. Concerns about large catches of young fish have increased as the use of roll netting by Japanese, South Korean and the fisherman has increase.

In 2010: 1) the international cap on Pacific bluefin went into effect the permits caches at 2002-2004 levels; 2), the catch quota for bigeye tuna was reduced 30 percent for three years; and 3) and the regulations for Atlantic Ocean fishing looked likely to be further tightened. At some bluefin market sales only 1 percent of the fish on sale had been caught at sea. The rest had been farmed.

Japan and Quotas and Limits on Blue Fin Tuna Fishing

Whenever there is talk is a shortage or overfishing of tuna eyes are inevitably cast towards Japan. The catch quotas of bluefin tuna in the late 2000s was 23,900 tons for Atlantic bluefin tuna in 2009, 24,900 tons for Pacific bluefin tuna in 2008, and 11,800 tons for southern bluefin tuna in 2009. The International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) is responsible for fish caught in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. ICCAT's quota was 13,500 tons in 2010, down from 20,000 tons in 2009.

Japan’s quota for Atlantic bluefin is about a quarter of what it was. In November 2006, Japan took the unusual step of voluntarily agreeing to cut its quota of Atlantic tuna in part to head off more severe imposed cuts.

Japan’s quota for southern bluefin tuna was 6000 tons in 2006. According to a group called the Commission Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT), Japan caught more twice the amounts of southern bluefin tuna that was allowed to catch between 2003 and 2005. Japanese fishermen said they just exceeded their quotas of 6,000 tons a years but based on the amounts sold the CCSBT estimated that between 10,000 to 16,000 tons were actually caught.

As punishment for overfishing the CCSBT halved Japan’s quota to 3000 tons. The government Fisheries Agency admitted that bluefin tuna was overfished and agreed to have the annual quota to 3,000 tons for five years beginning in 2007. There were worries the move might set off price hikes.

Southern bluefin tuna catches

The cuts and quotas are not expected to affect the supply or price of tuna by that much and many hope they will lead to more responsible fishing. The price of bluefin tuna rose 20 percent in Tokyo in 2007. In many cases sushi restaurants have not been able to pass on the costs to their customers and take a loss whenever their customers eat too much bluefin sushi. High prices have caused household consumption of blue fin tuna to decline 20 percent.

In November 2009, there were rumors that there might be shortages of bluefin tuna during the holiday season and that prices for the fish were going to spike. The government issued a statement that the rumors were not true and that suppliers stockpiled an ample supply.

At the first bluefin auction of the year at Tsukiji in 2010, there were 20 percent less fish than at the same time a year earlier. One wholesaler told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Since the first auction of the year, few tuna have been up for auction. Prices are up 20 percent on last year. I hope it’s not a bad sign.” An executive with a fishing organization said, “If catches and stockpiles decrease, and the economy recovers and demand increases, prices will rise.”

ICAAT and Limits on Mediterranean Bluefin Tuna

The ICCAT quota was 32,000 tons in 2006 (the true catch was believed to be well over 50,000 tons). In 2007 the organization agreed to cut the quota by 23 percent to around 25,000 tons by 2010 with a quota of 29,500 tons in 2007. Some wanted the quota to be cut to 15,000 tons. Japan agreed to reduce it catches from 2,830 tons to 2,175 tons and the European Union agreed to reduce it catches from 18,301 tons to 14,504 tons

ICCAT called for a 38.6 percent cut in the annual catch of Atlantic bluefin tuna in 2010, the biggest ever decrease. During a meeting in Tokyo in March 2008 ICATT decided to gradually cut bluefin tuna catch quotas in the eastern Atlantic to 25,500 tons in 2010 from the 29,500 tons in 2007. In November 2008, ICCAT reduced its quota 20 percent to 22,000 ton for 2009 and 19,950 tons for 2010. The previous quota had been 27,500 ton for 2009 and 25,500 tons for 2010. The season for purse seine fishing was limited to two month from mid April to mid June. In 2010 it was reduced to just one month from mid May to mid June. Many conservationists feel the quota is still too high and want further reductions made.

bluefin tuna catch </br/> In November 2010, ICCAT members agreed to reduce the annual quota of bluefin tuna from 13,500 tons this year to 12,900 tons in 2011. AFP reported some of 48 member nations favored a much lower cap (some suggested 6,000 tons) , or even a suspension of fishing, to ensure bluefin's long-term viability but ib the end the group decided to leave catch limits for the eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna virtually unchanged. But industry representatives and the governments that back them insisted the new catch limits were sufficient. “They will make it possible to reach maximum sustainable yield by 2022, which represents a balance between respecting natural resources and preserving the social-economic fabric,” said Bruno Le Maire, France's agriculture and fisheries minister in a statement. [Source: Marlowe Hood, AFP, November 29, 2010]

ICCAT scientists calculate that the new catch levels will put eastern Atlantic bluefin on track for a 70 percent chance of reaching sustainability by 2022. The same scientists, however, caution that the data upon which these estimates are based is spotty at best, while conservationists counter that a 30 percent risk of failure is too high. The head of the Japanese delegation, Masanori Miyahara, told AFP he was satisfied with the outcome, but said stronger compliance measures were needed. “The actual catch level will be around 11,000, which is a large reduction off current levels,” he added, noting that some members had pledged not to use up their quotas.

Banning nets in the Mediterranean that can capture thousands of bluefin tuna at once is a "realistic scenario," Fabio Hazin, president of the ICCAT said in November 2010."One of the things that is being discussed is the possible suspension of purse seine fishing and the caging activities." He was commenting on a joint call earlier in the day by four major non-governmental groups to suspend the use of the massive draw-string nets, which also serve as floating pens to transport tuna to off-coast farms where they are fattened for market.

In June 2010, the European Union banned industrial fishing of bluefin tuna for the rest of the year after fishermen already reached their quotas. That year the purse seine industrial season was between mid May and mid June. France sent out 17 boats, Spain six and Greece one. Small-scale operators with hooks and spears were allowed to continue. EU and ICCAT rules now prohibit spotter aircraft from flying in June.

More Bluefin Tuna Sold Than Caught, Hmmm

An estimated $4.5 billion worth or unreported, illegal catches have occurred in the Mediterranean during the 2000s, with much of the catching ending up in Japan. ICCAT estimates that the amount of Atlantic bluefin tuna actually caught is double the catch limits. In 2002, for example, the catch limit in the Atlantic and Mediterranean was 32,000 tons but ICCAT believes that 50,000 tons was actually caught. Such large amount are illegally caught because fishing nations refuse to set standards and procedures that could address the problem.

Tsukiji Roberto Bregazzi, a tuna industry analyst, has called the practice “intolerable tax free looting” and estimated the amount of illegally-caught tuna rose from 3,569 tons in 2004 to 24,297 tons in 2008. He told the fishing trade journal Interfish, “Thanks to a new generation of ultra-low freezing technology, Japanese fresh and frozen tuna traders are no longer faced with the urgency of its rapid market distribution. Tuna has thus become a commodity with which Japan can speculate.”

More than twice as many tonnes of Atlantic bluefin tuna were sold in 2009 and 2010 compared with official catch records for this threatened species, according to a report by Washington-based Pew Environment Group released in October 2011. This "bluefin gap" occurred despite enhanced reporting and enforcement measures introduced in 2008 by ICCAT. [Source: Marlowe Hood, AFP, October 17, 2011]

Trade figures showed that real catches of bluefin in 2009 and 2010 totaled more than 70,500 tonnes, twice ICCAT's tally for those two years, according to the report compiled "The current paper-based catch documentation system is plagued with fraud, misinformation and delays in reporting," said Roberto Mielgo, a former industry insider and author of the report. "Much more needs to be done." "This (catch) gap exists mainly because of loopholes in the ranching industry," Mielgo told AFP. "Essentially, more bluefin tuna are harvested from the ranches than initially reported when they are first transferred there."

The Pew study says that reported catch for bluefin tuna from 1998 to 2010 was 395,554 tonnes. By comparison, market figures for this period show 491,265 tonnes, leaving a gap of nearly 100,000 tonnes worth some two billion euros (2.7 billion dollars) at wholesale prices. These figures do not include what experts say is a sizeable black market in bluefin, along with fish that has been mislabeled as another species. The Pew report is based on official ICCAT statistics, as well as trade figures from Japanese customs, the US Department of Agriculture, Eurostat and the Croation Chamber of Economy.

Bluefin Tuna Tagging System

Pew and other environmental groups have called for the swift implementation of electronic tagging of fish to replace paper-based records, which they say are vulnerable to fraud. A new electronic system "should include a real-time reporting requirement and central database, which would allow information from ranches and vessels to be cross-checked instantly," said Lee Crockett, head of Pew's bluefin task force. ICCAT has committed in principle to such measures, but the timetable for implementation and funding have yet to be settled.

Tsukiji A scheme for catch-tracking or catch documentation, which stipulates that fishing nations certify that tuna has been caught in accordance with regulations, has been approved and set up by some of the tuna organizations. The scheme requires the tagging of fish for easier tracking from ship to market.

Scientist at Tokyo University of Marine Science and technology have developed a traceability system for tuna caught in the Indian Ocean and the pacific that will let consumers know it place of orpin using integrated circuits tags. Under the system the tags will placed inside the fish before they are frozen on vessels that catch them the data will be transmitted by via satellite and will be motored from that point on at ports and transportation centers until it reaches store shelves. Consumers can access information about the fish using their computers or cell phones and dat printed on the packaging.

Proposed Bluefin Tuna Ban

In March 2010, a proposal to ban the export of Atlantic bluefin tuna by declaring the fish an endangered species failed to become enacted at a meeting of the 175-nation Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITIES), also known as the Washington Convention, in Doha, Qatar. For a while it looked as if the Monaco-introduced proposal was going to pass. It was supported a United Nations conservation organization, the United States, the European Union, France, Italy and several European countries. On the eve of the vote bluefin tuna prices rose to ¥6,500 a kilograms, compared to ¥4,000 a couple months earlier. But in the end only 20 nations voted in favor of the ban while 68 voted against it, with 30 abstentions. A two thirds majority was needed for the measure to be passed.

It was a novel idea to try and restrict the bluefin trade using CITIES, which was set up to protect endangered species. Normally fishing matters are handled by fishing organizations like the International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). Supporters of the ban claimed bluefin tun were “on the verge of extinction.” Among the arguments used against the ban were that it hurt fisherman in developing nation and labeling bluefin fin endangered was not scientifically justified. In the end many countries chose to vote against the ban as economic concerns prevailed over conservation.

Traders and those in the fishing industry were relieved by the decision. "There has never been an instance of a fish caught to extinction," says Karl Petur Jonsson, a spokesman for Umami, a company that ranches bluefin tuna. "It's not like the American buffalo. The fish are down there." But environmentalist were worried about the future of bluefin tuna and the sustainability of the catch.

In May 2011, the Obama administration in May declined to protect the Atlantic bluefin tuna under the Endangered Species Act. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration instead classifies it as a species under concern while it awaits updated data outlining the effect of more-stringent fisheries management under ICAAT.

Australia Declares Southern Bluefin Tuna an Endangered Species

In November 2010, the Australian government announced it will formally protect the southern bluefin tuna by listing it as a threatened species. The species was categorised as "conservation dependent", meaning it can still be fished, but fisherman will have to establish a plan of management to stop its decline and support its long-term recovery. [Source: ABC News November 24, 2010]

Tsukiji Fish Market Auctions Environment Minister Tony Burke says a fishing ban in Australian waters would not necessarily reduce the global bluefin catch, because it is a highly migratory fish. "The species has declined in the past and while ongoing improvements in management measures are helping to stabilise the population, the breeding population is still considered to be less than 8 per cent of unfished levels," he said.

Chief executive of the Southern Bluefin Tuna Association, Brian Jeffriess, said the Government was ignoring scientific advice that stocks were recovering. "It really shows an appalling lack of judgment frankly, you know what the minister has is some scientific advice from his own personal scientific committee," he said. "There is not one person on that scientific committee who has any experience in value-added tuna, yet he's chosen to ignore the other scientific advice and chosen to accept that alternative advice. It's quite an extraordinary situation."

Humane Society senior program manager Alexia Wellbelove says the protection does not go far enough because the species can still be caught, but is a step in the right direction. "Internationally this species is listed as critically endangered, so internationally it's recognised that this species is in a bad way," she said. "By having some level of protection that's obviously better than nothing at all."Government moves to protect southern bluefin tuna.

Bluefin Tuna and Environmental Activists

Greenpeace and other environmental organizations have become increasingly critical of the bluefin trade. Many sushi restaurants in Europe don’t serve the fish. The WWF wants a more rigid “global catch documentation system” for all tuna species to be implemented that tracks tuna from the ocean to markets. Environmental groups such as Greenpeace argue that reducing the worldwide quota to 6,000 tonnes would give the stock a 66 percent chance to reach a sustainable level by 2020.

Environmentalist also want fleet sizes to be limited by the size of quotas. As its stand now excess capacity and profits determine how many fish are caught. To save the bluefin tuna scientist say its breeding and feeding grounds have to be protected, particularly in the Mediterranean and Gulf of Mexico. Japan want to limit the catch of smaller tuna-fishing nations while Europe wants to protect its canning industry. Poor countries want to expand their fleets while large countries want to limit fishing capacity.

Environmentalist complain that quotas are too high and even they are of little use anyway in that fishermen ignore regulations and lie about their catch. The quotas set by European Union are double what scientists have recommended — and fishermen routinely exceed those quotas by 50 percent. The United States imposes greater restrictions but fishermen are still allowed to bring home bluefin tuna they incidently catch while fishing for other fish species.

The advocacy group Center for Biological Diversity called on consumers, chefs and restaurateursin the United States to boycott bluefin tuna and places that serve it. Catherine Kilduff, one of the group's staff attorneys, said: "Bluefin tuna are teetering on the brink of extinction. If regulators won't protect these magnificent fish, it's up to consumers and restaurants to eliminate the market demand, and that means refusing to eat, buy or serve this species."

Bluefin Tuna and Greenpeace

Greenpeace is increasingly going after tuna boats accused of plundering stocks of bluefin tuna. It boats have pulled up alongside fishing bats from South Korea and Taiwan and managed to “confiscate” modern machinery capable of hugely increasing the catch.

In June 2010, Greenpeace activists clashed with bluefin tuna fishing vessels in the Mediterranean. The activists, using Zodiacs, tried to submerge a fishing net with sand bags to let the tuna free. at one point an activist was harpooned through the leg and injured by fishermen on a French boat, The victim, a Briton name Frank Hustin, was not in danger of dying but he was badly injured and needed surgery. Greenpeace said the activists were surrounded by fishing vessels and fishermen attached knives to long poles and fired flare guns at a Greenpeace helicopter. A French naval vessel had to be called in.

In November 2010, Greenpeace activists drove a car with a giant plastic tuna on the roof to offices of the French agriculture and Fisheries Ministry and blocked the entrance to draw attention to the depletion of Atlantic bluefin tuna stocks. Greenpeace accused the ministry of putting the interests of fisherman ahead of protection f the species.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). JNTO, Japan Zone,

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023