Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish

TUNA FISHING INDUSTRY

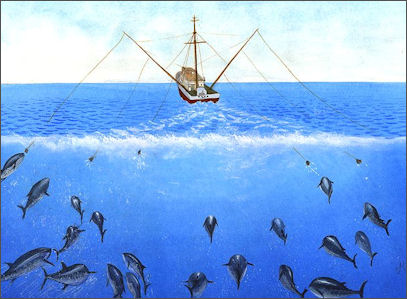

trolling for tuna The global tuna fish market was valued at US$40.7 billion in 2021 by SkyQuest. Pew Charitable Trust reported: Commercial tuna fisheries represent a significant part of the blue economy, with seven species—yellowfin, skipjack, bigeye, albacore, and Atlantic, Pacific, and southern bluefin—among the most valuable fishes on the planet. Whether canned or served as high-quality sashimi, tunas are not only a sought-after commodity, but also an important source of protein in countries around the world. And they also play a vital role as predators and prey in tropical and temperate waters while supporting the livelihoods of many artisanal fishers. [Source: “Netting Billions 2020: A Global Tuna Valuation” by Pew Charitable Trust, October 6, 2020]

In 2018, commercial fishing vessels landed about 5.2 million metric tons of the seven species, with an estimated dock value—the amount paid to fishers—of $11.7 billion. Both figures are up from 2016, when vessels landed 5 million metric tons, earning fishers an estimated $11.3 billion dockside. Products derived from this catch garnered an estimated end value of $37.5 billion. The bigger catch in 2018—up 12 percent from 2012—did not translate to higher revenue, however. The end value was down 2 percent from that base year.

The world tuna catch, according to the FAO, has increased from about 500,000 tons in 1950 to 1.7 million tons in 1970 to 2.7 million tons in 1990 to 5.8 million tons in 2000 to 6 million in 2004. At that time Japan consumed about one third of the world’s tuna catch. The United States was the second largest market for fresh tuna. China significantly underreported its catch. In the 200s, worldwide, the tuna fishing and processing industry is worth $3 billion a year. In the United States people consumed 900 million cans of tuna year. Between 1950 and the early 2000s the global catch of tuna rose tenfold to an average of 4 million tons in 2002, 2003 and 2004.

High demand for tuna products, however, has significantly depleted several populations, making sustainably managing tunas critically important. One way to support better population management is to improve our understanding of tunas’ importance to the global economy and marine ecosystems. Although it is difficult to put a monetary value on the role that tunas play in the marine environment, their benefits to fishers and the fishing industry can be estimated by looking at data on the catch and sale of tuna products around the world.

yellowfin tuna in a Philippine Market

Top Tuna Commercial Fish Species

Global Wild Fish Catch Ranking — Common name(s) — Scientific name — Harvest in tonnes (1000 kilograms)

3) Skipjack tuna — Katsuwonus pelamis — 2,795,339 tonnes

6) Yellowfin tuna — Thunnus albacares — 1,352,204 tonnes

20) Bigeye tuna — Thunnus obesus — 450,546 tonnes

34) Little tuna (Kawakawa, mackerel tuna) — Euthynnus affinis — 328,927 tonnes

43) Albacore — Thunnus alalunga — 256,082 tonnes

48) Longtail tuna — Thunnus tonggol — 234,427 tonnes

[Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2012; Wikipedia]

Websites and Resources: “Netting Billions 2020: A Global Tuna Valuation, Pew Charitable Trusts”, October 6, 2020 pewtrusts.org; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

See Separate Articles: TUNA: CHARACTERISTICS, SPEED, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; TUNA SPECIES: SKIPJACK, YELLOWFIN, ALBACORE, BIGEYE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; YELLOWFIN TUNA: FISHING, RECORDS AND A MISSING FISHERMAN ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SKIPJACK TUNA AND BONITO ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, HUNTING AND MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA SPECIES: ONE IN THE PACIFIC, ONE IN THE SOUTH, TWO IN THE ATLANTIC ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA COMMERCIAL FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA AND SUSHI ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA FISH FARMING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; LOW BLUEFIN TUNA NUMBERS: OVERFISHING, ORGANIZATIONS, QUOTAS AND PROTESTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Tuna as Food

Most canned tuna and the grilled tuna and tuna salads served in restaurants uses skipjack and yellowfin tuna.Skipjack tuna reach lengths of two and three feet. They live in tropical and subtropical waters. One of the most heavily fished of all fishes, they are found in huge schools near the surface that are scooped up with purse seine nets and caught with hooks and lines. Skipjack tuna stock are still healthy.

Rose Prince wrote in The Telegraph: “Tuna made headlines in 2009 year with the release of the film “The End of the Line”. Its focus was on the safety of the bluefin, the favourite sashimi and sushi fish of the Japanese. Bluefin is classed as endangered. At the time some press reports implied that all tuna were bluefin, canned, in sushi, in sandwiches. But this tuna is almost always skipjack or yellowfin, both available from sustainable sources. [Source: Rose Prince, The Telegraph, March 11, 2010]

“Yellowfin is the viable alternative to fresh bluefin. Reaching weights of up to 200 kilograms (440 pounds, yellowfin are found in all tropical and subtropical waters, but not in the Mediterranean. The appetite for fresh tuna in Western countries has encouraged fishermen to hunt using hi-tech methods that are not permitted in the Maldives. Most notorious are the purse seine nets, up to two kilometers (three miles) long, used to encircle and 'bag up’ huge numbers of fish.

Fish Oil, Omega 3s and the Benefits of Eating Fish

Tuna is regarded as a healthy fish to eat. The Japanese have traditionally eaten a lot of fish and they are the longest living people in the world. In 2000, the American Heart Association recommended that people eat salmon or tuna twice a week. It was the first time the group recommended eating specific things rather than offering general guidelines. Studies have shown that eating oily fish can significantly reduce the chances of getting a stroke, developing prostrate or breast cancer, suffering from depression or being stricken by a sudden, unexpected death caused by a severely abnormal heart rhythms.

Eating fish has been linked with low cholesterol levels and low rates of heart disease.Oily fish such as salmon and tuna are in rich fish oils, which in turn are rich in omega-3 fatty acids, an essential nutrient in the human diet. There is evidence that omega-3 fatty acids prevent inflammation, clot formation and clogging of blood vessels with fat and cholesterol and that a lack of omega-3 fatty acids may play a role in a variety of maladies, including bipolar disorder, heat arrhythmia, high blood pressure, heart disease, kidney failure, irritable bowel syndrome and rhomboid arthritis.

Omega-3 and omega-6 are essentially fatty acids that work together to promote good health, The human body can not make them so it is essential that people eat diet rich in them. Omega-3 are found in fish and certain oils such as canola and flaxseed and omega-6 are found in raw nuts and seeds. Omega-3 fatty acids are found in sardines, salmon, herring and some kinds of tuna. Shrimp, some kinds of tuna, haddock, clams, cod, and crab are low in Omega 3s.

Albacore tuna has about 3 times as much omegas as skipjack or “light” tuna. With fresh tuna, the belly is fattier — and more Omega 3 rich — than the meat on either side. According to Dr. Blonz: For higher levels of omega-3 fats, use albacore (white) tuna. One 3.5-ounce serving of water-packed albacore (drained) contains 2.5 grams of fat and 706 milligrams of omega-3 fats. Yellowfin and skipjack varieties used to make light tuna contain fewer omega-3 fatty acids than albacore, sometimes called a dark tuna. [Source: Dr. Blonz, Tri-Valley Dispatch]

See Separate Article BENEFITS OF EATING FISH AND CHOOSING THE BEST FISH TO EAT ioa.factsanddetails.com

Canned Tuna and Tuna Sandwiches

Canned tuna is low in fat, high in protein and by far the most popular shelf-stable seafood in the United States. According to Nielsen Holdings, a global data and analytics company, about 700 million cans of tuna were sold in the United States during 12 months in 2020 and 2021. [Source: Julia Carmel, New York Times, June 21, 2021]

Top to bottom (relative sizes are not correct)

1) Albacore tuna, Thunnus alalunga

2) Atlantic bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus

3) Skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis

4) Yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares

5) Bigeye tuna Thunnus obesus

Julia Carmel wrote in the New York Times: “Tuna sandwiches rose to prominence in the early 1900s, when people realized canned fish could translate into a quick and cheap meal that involved no cooking. By the 1950s, tuna had surpassed salmon in popularity, and during the 1980s, an estimated 85 percent of Americans had canned tuna in their pantries despite growing concerns about high levels of mercury in the fish.

“After a decadeslong decline in tuna consumption, a 2018 Wall Street Journal story suggested that millennials were to blame (“many can’t be bothered to open and drain the cans”), though newer brands offering more sustainable options were seeing their market share grow. Then, in 2020, canned goods took on great urgency as shoppers scrambled to buy shelf-stable food, not knowing how long the pandemic might last. That year, the global canned tuna market was valued at $8.57 billion, according to Grand View Research.

“According to the Seafood List, which is compiled by the Food and Drug Administration, there are 15 species of nomadic saltwater fish that can be labeled “tuna....Though Subway declined to disclose its tuna suppliers, Sage, who has been a Subway manager in California for three years, shared some details about how the product arrives at her location. (Sage asked not to use her full name out of fear of reprisal from her employer.) “The tuna comes in a case and inside the case, there are six aluminum pouches and it’s just like a pressed, vacuum-sealed slab of tuna,” Sage said. “It’s flaky and it’s clearly soaked in water — it’s like a brine, so it’s just soaked in salt water — and it’s just flaky tuna. We just spread it apart with our hands” — gloved, of course — “and mix it with mayo.”

“Sage said that each store follows corporate guidelines, which instruct that certain meats can stay out in the store’s refrigerated sandwich bar for up to 24, 48 or 72 hours. Tuna, she said, has a 72-hour counter life (the time frame was also confirmed by Subway’s spokesperson), though Sage said her store often replaces it before it hits three days. “We all agree — all of us that work there — it gets kind of gross,” she said.

Tuna Sandwich Mystery

What goes into a store- or shop-bought tuna sandwich, what “tuna” is comprised of, where it comes from and how it is processed can be mysterious and controversial and the butt of endless jokes. The issue was thrust into the limelight in 2021, when Subway — the world’s largest sandwich chain — was sued in a class-action lawsuit in California that claimed its tuna sandwiches were “completely bereft of tuna as an ingredient.” Subway, for its part, categorically denied the claims. “There simply is no truth to the allegations in the complaint that was filed in California,” a spokesperson told the New York Times.[Source: Julia Carmel, New York Times, June 21, 2021]

New York Times journalist Julia Carmel decided to get to the bottom of the issue and bought some Subway tuna sandwiches and froze the meat and sent it to a commercial food testing lab. She wrote: “Eventually, I found... a lab that specializes in fish testing.” A man there “agreed to test the tuna but asked that the lab not be named as he did not want to jeopardize any opportunities to work directly with America’s largest sandwich chain. For about $500, his lab could conduct a PCR test, which rapidly makes millions or billions of copies of a specific DNA sample, and try to tell me whether this substance included one of five tuna species.

“Subway’s tuna and seafood sourcing statement says the chain only sells skipjack and yellowfin tuna, species that a lab would recognize as Katsuwonus pelamis and T. albacares. To procure the sandwich specimens, I visited three Subway locations around Los Angeles. It seemed logical to order only tuna on the sandwiches — no extra vegetables, cheese or dressing — as the lab was already wary about the challenges of identifying a fish that’s been cooked at least once, mixed with mayo, frozen and shipped across the country.

“Jen, a former Subway “sandwich artist” who worked at a location in Iowa for a year, said she couldn’t imagine what incentive Subway would have to replace the tuna with anything else. (Jen also asked not to use her full name out of fear of reprisal from her employer). “I dealt with the tuna all the time,” Jen said. “The ingredients are right on the package, and tuna is a relatively cheap meat. There would be no point to making replacement tuna to make it cheaper.”

“Finally, after more than a month of waiting, the lab results arrived. “No amplifiable tuna DNA was present in the sample and so we obtained no amplification products from the DNA,” the email read. “Therefore, we cannot identify the species.” “The spokesperson from the lab offered a bit of analysis. “There’s two conclusions,” he said. “One, it’s so heavily processed that whatever we could pull out, we couldn’t make an identification. Or we got some and there’s just nothing there that’s tuna.” (Subway declined to comment on the lab results.)

“To be fair, when Inside Edition sent samples from three Subway locations in Queens out for testing this year, the lab found that the specimens were, indeed, tuna. Even the plaintiffs have softened their original claims. In a new filing from June, their complaints centered not on whether Subway’s tuna was tuna at all, but whether it was “100 percent sustainably caught skipjack and yellowfin tuna.” With all testing, there are major caveats to consider. Once tuna has been cooked, its protein becomes denatured, meaning that the fish’s characteristic properties have likely been destroyed, making it difficult, if not impossible, to identify. All of the people I spoke with also questioned why Subway would swap out its tuna. “I don’t think a sandwich place would intentionally mislabel,” Rudie from Catalina Offshore Products said. “They’re buying a can of tuna that says ‘tuna.’ If there’s any fraud in this case, it happened at the cannery.”

Tuna Fishing

Julia Carmel wrote in the New York Times: “The majority of commercially sold tuna is caught by fishermen working in exclusive economic zones. (EEZs are areas that extend roughly 200 nautical miles from each country’s coast; the United States, with more than 13,000 miles of coastline, controls the largest EEZ in the world, containing 3.4 million square nautical miles of ocean.) [Source: Julia Carmel, New York Times, June 21, 2021]

“There are five organizations that manage regional fisheries within those economic zones. Their job is to enforce regulations and “make sure the predators of ocean ecosystems remain in the ocean and not on our plates,” according to Barbara Block, a professor of marine sciences at Stanford University who codirects Stanford’s Tuna Research and Conservation Center. “Removal at sustainable levels is a priority of many,” Block added in an email, “but practiced by few.” Some species of bluefin tuna, for example, have become endangered following decades of overfishing.

According to the Pew Charitable Trust: Tuna from the Pacific has both the lowest price per metric ton and the highest total value of any region. This seeming paradox is because purse seine skipjack fisheries in that ocean are enormous, and that catch is destined for low-priced cans. The price per ton is low, but overall tonnage is very high. In 2018, 66 percent of tuna landings came from these waters, and sales of tunas from the Pacific made up almost two-thirds of the global dock and end values in all the years studied. Commercially landed Pacific tunas generated dock values of $7.1 billion in 2018, down from more than $8 billion in 2012. The end value of Pacific tunas surpassed $26 billion for each year studied. Conversely, tuna from the Southern Ocean has by far the highest price per metric ton and lowest total value—at the dock and at the final point of sale—because these fisheries target very small volumes of highly valuable southern bluefin.

International Tuna Market

According to Pew: Based on data reported to the world’s regional fisheries management bodies, Indonesia and Japan were consistently the top two tuna fishing nations from 2012 to 2018, in terms of total reported landings. In 2018, Indonesia landed 568,170 metric tons, followed by Japan at 369,696 metric tons. Compared to 2012, nine countries remained among the top 10 fishing nations, by landings. Although Mexico’s landings remained consistent, Kiribati increased its landings by 152 percent, replacing Mexico on the list in 2018. Since 2012, Papua New Guinea has risen in the ranks from the eighth-largest lander to the third—boosting landings by 37 percent. Spain and Ecuador have also increased landings, by 12 percent and 20 percent respectively. In contrast, the United States and Philippines reported drops in landings, by 18 percent and 35 percent respectively.

Japan leads the world in tuna consumption but not as much as it once did as sushi is now a global phenomena. Japan consumed one third of the world’s tuna production and 95 percent of the world’s toro in the 2000s. The United States consumed roughly another third at that time. In 2003, about 458,000 tons of raw tuna was sold in Japan. Of this, 43 percent was caught in Japanese waters. The rest was imported. The consumption of raw tuna peaked in the early 1990s at around 528,000 tons.

In the 2000s, about 1,200 fishing boats engaged in oceangoing, long-line tuna fishing worldwide. Ninety percent of these were from Japan, China, South Korea and Taiwan. These vessels often stay out at sea for about a year, conducting only a couple of catches during that time.

In January 2009, the Japanese government said that its longline tuna fleet would be cut by 10 percent to 20 percent in response to higher international restrictions on tuna catches. The number of ocean-going vessels would be reduced from 390 to between 310 and 380 ships. The number of coastal vessels would be reduced from 349 to between 300 and 310 ships. The move is expected to result in the loss of 1,000 jobs and raise the price of tuna.

Tuna Fishing Methods

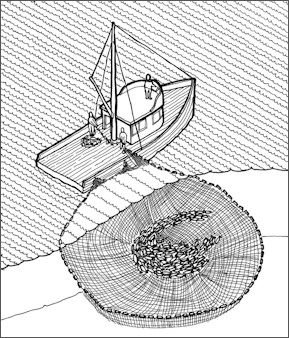

Julia Carmel wrote in the New York Times: “ “There are three methods these fisheries use to catch tuna: 1) purse seining, 2) longlining and 3) pole-and-line fishing. Pole-and-line fishing is the kind hobbyists take part in: sitting on a boat and bringing in one catch at a time. Larger fishing operations tend to rely on the other two methods. Purse seiners drop a large, round wall of netting around a school of fish and then “purse” the bottom of the net shut to prevent fish from escaping. Longliners drop one 30- or 40-mile-long line into the water, then wait for the fish to catch on hundreds (or thousands) of hooks. [Source: Julia Carmel, New York Times, June 21, 2021]

Barbless hooks, lines and poles are used primarily to catch yellowfin tuna and skipjack. Fishermen stand at the side of the boat with short poles with lured barbless hooks and sardine chum is thrown in the water. Tuna feed on the chum by the thousands and the fishermen yank them out with poles that have a swing on them. The fisherman need to be strong. The boats stay out at sea until its refrigerated hold are filled with fish.

Yellowfin and bigeye tuna are pursued with circle-hook-equipped longline fishing boats. The stocks of these fish are particularly large in the western and central Pacific Ocean, which is over seen by the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, a group made up of 27 members in Asia, the Pacific and Europe, which are roughly divided between those that have exclusive economic zones in the area and those that exploit the region with ocean-going-vessels.

Many kinds of tuna are caught using purse-seine nets, which are capable of encircling and catching entire schools of tuna. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and other major tuna fishing nations began using GPS devices in 2007 to monitor the activities of tuna fishing boats in the central and western Pacific Ocean, an area rich in yellowfin and bigeye tuna.

See Bluefin Tuna

Tuna Fishermen, Dolphins and Sharks

In the late 1980s it was estimated that over a million dolphins a year were being killed by fisherman trying to catch tuna, squid and other food fish. Most of the dolphins died by getting entangled in drift nets up to 40 miles long or encircled by purse seine nets, used to capture schools of tuna.

Tuna fishermen have traditionally looked for schools of dolphins because yellowfin tuna tend to congregate underneath them. Scientists speculate the tuna do this because the dolphins protect them from predators and help them locate food. The confusion of being trapped in a seine net often forces the school of dolphins to sink to the bottom of the net in a helpless pile. Dolphins could easily prevent themselves from being trapped by purse string nets that they could easily jump over but they don?t. Fortunately drift nets are no longer used and techniques have devised to drive the dolphins from the seine nets without affecting the tuna catch.┺

In 2000, the United States established the Dolphin-Safe Tuna Tracking and Verification Program to monitor the domestic production and importation of all frozen and processed tuna products nationwide and to authenticate any associated dolphin-safe claim. Changes introduced in U.S. fisheries in the 1990s reduced the numbers of dolphins accidentally caught by a third. The United States introduced the dolphin-safe label which placed on cans of tuna in which tuna were caught using methods that minimized the harm to dolphins. Starkist, Chicken of the Sea and Bumble Bee all went along. In 2002, the Bush administration changed the definition of dolphin-safe to allow the encircling of dolphins to catch tuna in the name of free trade and globalization and a concession to the Mexican fishermen who want access to the American market.

dolphins In the mid 2000s it was estimated that 300,00 dolphins, porpoises and whales were still being killed by fishing nets each year, with dolphins in the Philippines, India and Thailand being under the greatest threat. Many of those killed in the open sea are killed by gill nets. Deaths can be reduced by using simple, low cost safety measures such as making slight modifications to fishing gear.

Sharks are also often caught as bycatch by tuna fishermen, In 2011, AFP reported: Countries involved in bluefin tuna fishing have decided to do more to protect a species of shark against collateral killing, environmental groups. Elizabeth Griffin Wilson of the Oceana group said the 48-state International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) had ruled that tuna fishermen who find a silky shark in their nets must put it back in the sea. The only exceptions should be coastal communities who hunt the shark for consumption, she said. Wilson hailed the move, saying studies had shown the silky shark to be highly vulnerable to long-line tuna fishing in the Atlantic. The US Pew Environment Group also praised the decision, while deploring the fact that another shark, the porbeagle, was not similarly protected. Marine protection groups claim that three-quarters of migratory shark species that inhabit bluefin fishing areas are threatened with extinction. Pew wants fishermen to use new materials that allow sharks to escape, such as nylon fishing lines that can be severed by a shark but not a tuna. [Source: AFP, November 19, 2011]

Hard Life of Small Tuna Fishermen off the Coast of Kenya

Reporting from Vanga, Kenya, Wanjohi Kabukuru of Associated Press wrote: “Tuna is not for everyone,” lamented 65-year-old Chapoka Miongo, a handline fisher on Kenya’s south coast, from his dugout canoe.He's one of many artisanal fishers in Shimoni, a bustling coastal town 82 kilometers (51 miles) south of Mombasa, dotted with dhows, dugout boats, outrigger canoes and skiffs anchored on the beach landing site. Scores of fishmongers, processors and traders line the shoreline awaiting the fisherfolk to return. [Source: Wanjohi Kabukuru, Associated Press, July 7, 2022]

“My canoe is only suitable for the near shore and only those with the big boats and money can access tuna,” he said. Miongo explained that warming waters due to climate change forced tuna species to alter their migration patterns, making it harder for local fishers to catch them. Fish stocks have also decreased due to a lack of sustainable fishing by larger vessels.

The Shimoni channel, previously a well-known haunt for tuna, benefits from the north and south easterly monsoons which can lead to substantial catches, according to records kept by the Kenya Fisheries Service. But the current monsoon has been unkind to Miongo. He can barely fill his bucket: his modest catch of the day includes a motley batch of emperor fish.

purse seine net

Yellowfin tuna in particular, which fetches competitive prices at the market, can feel like a “lucky break” for fisherfolk, explained 60-year-old prawn fisher Mazera Mgala. After a seemingly futile five-day hunt, scouting fish landing sites in Gazi Bay, the Shimoni channel and Vanga seafront for the yellowfin tuna, one weighing six and a half kilograms was finally caught by an outrigger canoe fisherman at the Shimoni channel.

Miongo and Mgala are among just over 1,500 fisherfolk who rely on the rich marine waters of the channel. In Miongo's three decades of fishing, he says large foreign ships, more young men opting for artisanal fishing due to a lack of white-collar jobs and higher education opportunities, and a changing climate are depleting livelihoods.

Vanga fisherman Kassim Abdalla Zingizi added that most artisanal fisherfolk lack the skills, knowledge and financial support to compete with larger foreign vessels, mostly from Europe and Asia, which deploy satellite tracking technologies to trace the various tuna shoals all over the Indian Ocean. “Back in the day I would start fishing in the early morning and three to four hours later I would be through as I had caught enough fish,” said Mazera Mgala, who started fishing in 1975 and would dive in the ocean in his youth among vibrant corals and abundant fish. “Nowadays, I stay longer at sea and still catch less.”

The Kenyan government is implementing an economic strategy that will address the effects of climate change on the livelihoods of those on the coast, as well as boost skills among artisanal fisherfolk and promote more sustainable fishing practices, said Dennis Oigara from the Kenya Fisheries Service.

Subsidies, Big Boats and Tuna Shortages in the Indian Ocean

Wanjohi Kabukuru of Associated Press wrote: “Subsidies for large fisheries — which have long been blamed for destructive fishing practices — have featured prominently at World Trade Organization talks for over a decade with no resolution. In 2022, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, who is responsible for the region's tuna regulations, was criticized for not implementing measures to protect several tuna species from overfishing. [Source: Wanjohi Kabukuru, Associated Press, July 7, 2022]

After catch limits for two tuna species were exceeded between 2018 and 2020, conservation groups lambasted the tuna commission for what they called a “decade of failure" which left tuna stocks “increasingly in peril.” The World Wildlife Fund for Nature called for a global boycott of yellowfin tuna. The Maldivian government, which unsuccessfully proposed that members of the tuna commission reduce their catch by 22 percent from 2020, said it was “extremely disappointed” by the inactivity.

Christopher O’Brien, the commission's executive secretary, said the number of active fishing vessels in the Indian Ocean are decreasing. “There are currently over 6100 vessels licensed to fish for Indian Ocean tuna species. In 2020 there were just over 3300 active vessels,” he explained. Small dugout and outrigger canoes are not among these 6100 vessels registered by the tuna commission, which is dominated by industrial fishing fleets.

Tuna Processing

gutting skipjack

Julia Carmel wrote in the New York Times: After the tuna fish are brought ashore: “the fish is cleaned, sorted and, eventually, canned. Dave Rudie, the president of Catalina Offshore Products in San Diego (the former tuna capital of the world), works with a cannery that sells about 1 million cans of tuna each year, 10,000 of which contain bigeye sourced from him. “The really perfect colored tuna — the brightest red — goes to the sushi bars,” Rudie said. “Tuna that’s a little bit paler in color will go more for the cooking, where you sear the outside and it’s raw in the middle.” “We also get some more off-color tuna and that off-color tuna, we cut it up and freeze it,” he continued. “And we send it up to a cannery in Oregon.” [Source: Julia Carmel, New York Times, June 21, 2021]

“Canneries tend to follow the same general process. “Most canned tuna is caught by purse seiners and it’s frozen on the boat,” Rudie said. “They’re going to take it to a cannery, where they’re most likely going to cook it once, and then they’re going to pull the meat off the bone, and they’re going to put it in a can, and then it’s going to get retorted — cooked a little bit — to sterilize it the last time before they seal the can.”

“Then there’s the issue of labeling. When Oceana, an organization focused on ocean advocacy, conducted one of the largest “fish fraud” investigations in the early 2010s, it discovered that “seafood may be mislabeled as often as 26 percent to 87 percent of the time for commonly swapped fish such as grouper, cod and snapper, disguising fish that are less desirable, cheaper or more readily available.”

Tuna Stocks

According to a 2022 United Nations reported: Tuna stocks are of upmost importance because of their large volume of catches, high economic value and extensive international trade. Moreover, their management is subject to additional challenges owing to their highly migratory and often straddling distributions. At the global level, the seven species of tunas of principal commercial importance are albacore (Thunnus alalunga), bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus), skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and three species of bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus, Thunnus maccoyii, Thunnus orientalis). [Source: “State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022", Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations]

The main commercial tunas contributed 5.7 million tonnes of catch in 2019, a 15 percent increase from 2017 but still 14 percent lower than the historical peak in 2014. On average, of the principal commercial tuna species, 66.7 percent of stocks were fished within biologically sustainable levels in 2019, slightly higher than the all-species average, but unchanged in comparison with 2017.

Tuna stocks are closely monitored and extensively assessed, and the status of the seven above-mentioned tuna species is known with moderate uncertainty. However, other tuna and tuna-like species remain mostly unassessed or assessed under high uncertainty. This represents a major challenge, as tuna and tuna-like species are estimated to account for at least 15 percent of the total global small-scale fisheries catch. Furthermore, market demand for tuna remains high, and tuna fishing fleets continue to have significant overcapacity. Effective management, including better reporting and access to data and the implementation of harvest control rules across all tuna stocks, is needed to maintain stocks at a sustainable level and in particular rebuild overexploited stocks. Moreover, substantial additional efforts on data collection, reporting and assessment for tuna and tuna-like species other than the main commercial species are required.

Tuna Recovery

In late 2000s and early 2010s there were headlines about tuna species, especially bluefin tuna, being in rapid in decline. Most types of tuna were deemed at threat of extinction in 2011. But since some of the species have made a come back. In 2021, scientists at a meeting of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) said that tuna was starting to recover after being fished to the edge of extinction and a decade of conservation efforts, according to the official tally of threatened species. But some tuna stocks remain in severe decline. [Source: Helen Briggs, BBC, September 4, 2021]

The BBC reported: “The latest update — revealed encouraging signs for four of seven tuna species: “The Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) moved from Endangered to Least Concern; The Southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) moved from Critically Endangered to Endangered; The albacore (Thunnus alalunga) and yellowfin tunas (Thunnus albacares) both moved from Near Threatened to Least Concern.

“Tuna stocks in some areas remain of concern, such as bluefin tuna in western parts of the Atlantic and yellowfin in the Indian Ocean. "The take home message for the general public is that things like albacore tuna — which is the one that is widely on supermarket shelves — is of least concern now — it means that what they're eating has been sustainably caught and is well managed," Craig Hilton-Taylor, who heads the IUCN Red List, told BBC News.

After a decade of efforts from conservationists and industry, including strict fishing quotas and a crack-down on illegal fishing, populations in some parts of the ocean appear to be recovering. Tuna have been at the forefront of efforts to make fishing practices more sustainable. The likes of skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye and albacore tuna are consumed by millions of people across the world and one of the most commercially valuable fish.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA, graphs and graphics from The Pew Charitable Trusts (“Netting Billions 2020: A Global Tuna Valuation, October 6, 2020 pewtrusts.org)

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023