Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish

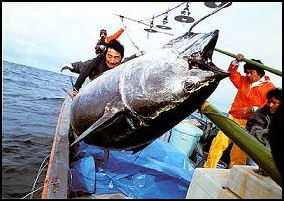

BLUEFIN TUNA FISHING INDUSTRY

Spanish purse seine vessels Bluefin tuna supports a multi-billion dollar market, with demand for their meat increasing most years. About $74 million worth of production happens in Baja California, Mexico alone. The European Union’s tuna industry is dominated by Spain. The industry there is centered around the southeaster region of Murcia. Italy, Croatia and Malta have large farms. Much of the meat is exported to Japan or at least used to sushi.

Much more skipjack tuna and yellowfin tuna are caught than bluefin tuna. Bluefin tuna doesn’t even make it into the Top 100 of the world’s most caught fish. What make it special is that it can fetch prices. A single bluefin tuna fish can be worth more than several nets full or herring or mackerel. Bluefin tuna accounted for 2.5 percent, or 56,828 tons, of the 2.35 million ton worldwide catch in 2003 of all kinds of tuna. Still this enough cause number to decline in many places. The WWF estimates the current fleet of is 70 percent larger than is needed for a sustainable catch. Lower prices encourage existing fishermen to catch more fish to compensate for losses.

Because bluefin tuna fishing is so lucrative the Italian, Asian and Russian mafia are involved. A scientist with the FAO told AP, “One big tuna can be worth as much as the most expensive Mercedes-Benz. How do you expect criminal organizations not to want to be in it”.

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

See Separate Articles: TUNA: CHARACTERISTICS, SPEED, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, HUNTING AND MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA SPECIES: ONE IN THE PACIFIC, ONE IN THE SOUTH, TWO IN THE ATLANTIC ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA AND SUSHI ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA FISH FARMING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; LOW BLUEFIN TUNA NUMBERS: OVERFISHING, ORGANIZATIONS, QUOTAS AND PROTESTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Bluefin Tuna Fishing Methods

Bluefin tuna have traditionally been caught by commercial fishermen with hooks and lines, purse seine and haul seine nets and harpoons. Small-scale operators often use hooks and spears. In Japan, bluefin tuna tend to be caught using the rod-and-line technique or long lines. In the Atlantic they are often caught with spotter planes and harpoons that electrocute the fish dead with hundred of volts of power. Favored fishing places include the Mediterranean, near the Azores and the waters off Boston.

The bluefin tuna season in Cape Cod begins in late June when the fish migrate to the North Atlantic. Spotter planes used to find tuna generally get 25 percent of the money from the sale of the fish. Electric harpoons are preferred for killing the tuna because fish that are caught with a line fight for a long time, which raises their body temperature and produces an unwanted flavor called “ya-ke”.

Immediately after being caught and brought on board bluefin tuna caught off Cape Cod are gutted, instantly frozen at -76̊F and put in coffin-like containers packed with ice and often transported later that day via cargo jets to Japan. Even fish caught by sport fishermen often end up in Japan. Japanese wholesalers have contacts at sport fishing dock in Miami and other places. At many ports where blue fin are brought, "tuna techs" from Tsukiji educate American fishermen about the tuna's “kata”, or ideal form, and what to look for in color, texture, fish content and body shape.

The bluefin tuna is also a prized sports fish, valued for its speed and fighting ability, Both Ernest Hemingway and Zane Grey fished for them. Big, old fish hiding in caves are pursued with almost weightless nylon-Kevlar lines up to 750 meters long and equipped with lights and tiny cameras.

The bluefin tuna is also a prized sports fish, valued for its speed and fighting ability, Both Ernest Hemingway and Zane Grey fished for them. Big, old fish hiding in caves are pursued with almost weightless nylon-Kevlar lines up to 750 meters long and equipped with lights and tiny cameras.

Describing the fight endured by a commercial fisherman Kenneth Brower wrote in National Geographic: ““Eight miles offshore, drifting with three lines out baited with mackerel, we had a strike. Sheldon Gillis, Captain Cameron’s assistant, fought the fish. There was a taut twang each time the bluefin took out line. Twenty minutes later, a good distance off the stern, the fish made its first appearance. Gillis judged it to be about 700 pounds. He reeled in furiously each time the tuna gave him the chance, and he was sweating now despite the cool of the morning. After another 20 minutes came the loud, slapping bang of tail fin against the stern. Hoisted aboard through the tuna door, the fish lay on its side, perfectly still and enormous on the mat. Out of water, it looked like some kind of wonderful machine, biologically inspired and poured of living metal. [Source: Kenneth Brower, National Geographic, March 2014]

Almadradas, Tonnar and Traditional Mediterranean Tuna Fishing

Fishermen have been catch bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean for more than 3,000 years. Using a technique that has been employed since Roman times, fishermen in southern Spain and Italy set up fixed trap nets known as “almadradas “ in Spanish and “tonnara “ in Italian — a labyrinth of nets anchored in shallow waters near the coast that funnels fish into chambers, where they were slaughtered. [Source: Fen Montaigne, National Geographic, April 2007]

In the mid 1800s around a hundred of these tuna traps harvested up to 15,000 tons of bluefin annually. The fishery was sustainable, supporting thousands of workers and their families. Today all but a dozen or so have been closed because of coastal development, pollution and overfishing. One of the last remaining ones that is open was built by Arabs in the 9th century on the island of Favignana of Sicily. In 1864 fisherman there caught a record 14,020 bluefin, averaging 425 pounds. In 2006, they caught around 100 fish, averaging 65 pounds. That year only one “mattanza” — in which the tuna and channeled into a netted chamber and slaughtered at the surface by fishermen who kill them with gaffs — was held. There are now plans to dress fishermen in historic costumes and reenact the mattanza.

Tunisians around Sidi Daoud on the western coast of Ca Bon use an interesting methods of catching tuna that dates back to ancient times. Kilometers of nets are positioned along the route taken by tuna during the spawning season. They are set up so they are perpendicular to the shore and force the fish to swim into places where they are trapped by the nets.

In May and June, fisherman in boats surround the places the fish are trapped. They pull up the nets while shouting and singing traditional songs. As the bottom of the net reaches the surface the water boils with tuna as large as 250 kilograms. The fishermen jump into the water with knives and slash and stab the fish to death.

Catching Bluefin Tuna in Japan

The best bluefin tuna caching grounds in Japan are said to be in the Tsugaru Strait off Omamachi in Aomori Prefecture in northern Honshu. Bluefin tuna unloaded at the port in Omamachi are known as Oma Maguro. They tend to sell for double the price of tuna caught elsewhere.

The best bluefin tuna in the Tsugaru Strait are caught during the winter when the waters in the strait are rich in small fish eaten by tuna and it is not unusual for tuna weighing 300 kilograms or more to be caught. Bluefin tuna are particularly valuable at that time of year because the are rich in fat and tuna supplies worldwide tend to decline in the winter. Fishermen risk their lives going out in the rough seas to catch tuna. Some lose fingers after getting them caught in fishing lines while trying to pull in large fish. One fisherman told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “In winter, I go out fishing even if the wind is blowing 70 kilometers per hour because its worth the danger.”

purse seiner catch There is conflict there between fishermen using the rod-and-line technique and other who use long lines. In recent years as the price of bluefin tuna has risen and cost of fishing have increased, long line fishermen have intruded on fishing grounds reserved for rod- and-line fishing. The long lines are sometimes 3,000 meters long. Not only do conservation oppose the method other fishermen don’t like them because the long lines can become entangled created a mess in popular fishing areas.

Penalties of one year in prison and ¥500,000 fines for repeated violations don’t do much to deter the long line fishermen. There have been cases where long line boats have been chased and surrounded by rod-and-line boats who cut the lines of the long-line fishermen.

In January 2010, a 232.6-kilogram bluefin tuna was sold at Tsukiji for ¥16.28 million (about $175,000), or ¥70,000 a kilogram. The fish was caught off Oma-machi, Aomori Prefecture.

Modern Methods of Bluefin Tuna Fishing

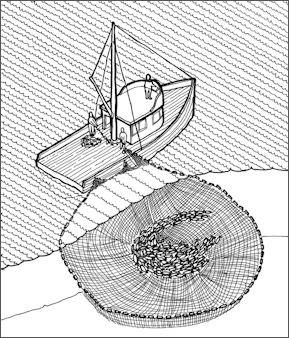

Bluefin tuna are pursued by high tech fleets often with the help of spotter planes. Fishing vessels using echolocation and spotter planes have become so efficient at locating schools of bluefin tuna and netting them with purse seine nets the season’s quota can be reached in 10 days.

About 70 percent of the bluefin caught in the Mediterranean are netted by industrial purse-seine vessels with vast, sack-like nets that encircle tuna as they gather to spawn. Tuna schools are spotted with light planes and caught with a one cast net and slowly pulled to the farming area and placed in a 50-meter wide “pond” set in the sea. A spotter pilot in the Mediterranean, “There’s no way for the fish to escape — everything is high-tech...I couldn’t stand the way they fished with no care for the quotas. I saw these people taking everything, They catch whatever they want. They just see money on the sea. They don’t think what will be there in ten years.” Before the introduction of purse-seine fishing and tuna ranching in the 1990s, bluefin were caught using more artisnal and traditional methods.

The Gulf of Sidra in the Mediterranean off the coast of Libya has been described as “one of the last tuna Shangri-las,” with the average size of bluefin tuna being around 190 kilograms. Describing a fishing operation there in 2006 Fen Montaigne wrote in National Geographic, “Three other spotter aircraft were prowling illegally, relaying tuna sightings to some of the 20 purse seiners in the water below...Just before I arrived...two purse-seine fleets net 835,000 pound of bluefin, sharing more than two million dollars.”

One Mediterranean fisherman told National Geographic, “the price is cheap because more and more tuna are being caught. My only weapon is to catch more fish. It’s a viscous circle. If I catch my quota of a thousand tuna, I can’t live because the price is very cheap. I want to respect the quotas, but I can’t because I need to live, If boats of all countries respect the rules, and other don’t respect the rules, the fishermen who respected the rule is finished.”

Bluefin Tuna Stockpiles and Sales

Purse seine illustration

Bregazzi claims that 47,000 tons of tuna has been stockpiled in Japan as of June 2009 in the anticipation that tuna fisheries will become depleted enough to send the price of tuna through the roof. In Japan, tuna are stored for long periods in warehouses where temperatures are kept at -60 degrees C. The stockpile of bluefin tuna in freezers across Japan is said to be enough to last for between a year and 18 months. Such huge stockpiles of tuna lead to prices of tuna falling by 10 percent in 2009 while there was talk of tuna going extinct.

Bluefin tuna caught off New England is sold at the docks to Japanese buyers who grade the fish for freshness color, fat and shape and offer prices based on the going rates at Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo that day. The purchased fish is packed in ice, transported to the airports and loaded on Japan Airlines planes at New York's Kennedy Airport for a 15 hour flight to Tokyo, where a single tuna can cost $80,000.

Describing the scene at a pier in Bath, Maine, Theodore Betsor wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, "After 20 minutes of eyeing the goods, many of the buyers return to their trucks to call Japan by cellular phone and get the morning prices from Tokyo's Tsukiji Market...The buyers give written bids to the dock manager, who passes the top bid for each fish to the crew that landed it."

"Each secret auction bid is examined anxiously by a cluster of young men. After a few minutes deals are closed and the fish are quickly loaded onto the backs of trucks in crates of crushed ice." American fishermen usually get around $10 to $20 a pound on the docks for bluefish catches.

Japanese imports of fresh bluefin tuna worldwide increased from 957 tons in 1984 to 5,235 tons in 1993. The price peaked in 1990 at $34 per kilogram when a typical 350 pound fish sold for around $10,000. As of 2008, bluefin was selling for $23 a kilogram. Higher prices are charged for really high quality fish.

Selling Blue Fin Tuna in Japan

The main inner market tuna auction at Tsukiji Fish Market in Tokyo begins at 5:30am every day (except Sunday, holidays and two Wednesdays a month) and is usually over within 30 minutes. There are restriction on how close visitors can get to the action.

About 3,000 frozen blue fin tuna are sold every day, with some fetching prices of $10,000 or more. The fish are numbered and displayed on the floor of a vast tuna shed. Before the auction the bidders cut off small pieces of dark red meat from the fish and examine it for color, texture and fat and oil content and make notes on scraps of paper. Oily fish are worth more than dry ones. Cuts from the stomach are examined for marbling and fat. The more marbling and more the fat the more valuable the fish is.

The fish are numbered and the bidders use hand gestures to make their bids which the auctioneers recognize with sounds that resemble barks. Masami Eguchi, a tuna auctioneer sells around 200 fish in a half an hour (one every nine seconds). "I have to recognize the highest bidder instantly," he told National Geographic. "No delays are allowed. There are dozens of auctioneers. Each one has his own chant, his own rhythm. You have to pick a style that works for you and your buyers. And you have to work fast." Other fish are sold in auctions with many of the bids taking place with hand gestures concealed under towels. It is important that the fish stay fresh so everything is done at a rapid pace while most people are asleep.

The tuna auction begins around 5:00am. Describing it, Kathyrn Tolbert wrote in the Washington Post, “the fish were laid out in neat rows on the floor of the chilly warehouse, giving off a faint frozen mist under the fluorescent lighting...Men in work shirts and rubber boots bent over the solid carcasses, inspecting them by lifting a three-inch flap of skin that had been neatly cut open on each one, peering at the cut-off tail end with flashlights. The weight of each tuna was written in kilograms.”

magaro at the fish auction at Tsukiji “A cowbell rang, and the auctioneer launched into the rhythmic chanting that marks this ritual, moving slowly through the rooms flanked by several men with notepads as they buyers hovered near their choices and made finger signals...the tuna were being sold in groups of six or seven at a time.”

After tuna is purchased it is sliced in half with a maguro-bocho, a five-foot tuna knife that resembles a samurai sword and cut into smaller pieces are sold to other buyers, restaurants, supermarkets and retailers. The knives are made by fusing iron and steel bars together at 900 degrees F under a power hammer and a then ground in flurry of sparks. Professional knifemakers say they one in three are rejects.

Around 3:00am vehicles begin bringing in fresh and frozen fish, much of which is already sold by 4:30am. Workers take a lunch break around sunrise and unwind with a dinner and beer around 8:30 in the morning. Intermediate wholesalers are very busy between 6:00am and 9:00. Larch hunks of frozen tuna are cut into pieces with saws and adzes and fish and seafood of all kinds is boxed and prepared for deliveries. By 10:30am the activity has subsided, stalls are empty and the floors are being hosed down. The market closes around noon.

Bluefin tuna worth over a $150,000 have been sold at Tsukiji. In 2001, a 202-kilogram tuna caught in Tsugaru Straight near Omanachi I Aomori Prefecture sold for a whopping $173,600 or about $800 a kilogram.

In recent years prices have come down. Bluefin tuna was selling for ¥3,000 a kilogram in 2008, compared to ¥4,500 a kilogram in 1989.

More and more the amount bluefin tuna available on a given day is unreliable and buyers are relying more and more on large commercial freezers to store supplies so they don’t run out. Tuna frozen with the special “flash” method can be kept for up to a year with no perceivable change in taste.

Pacific Bluefin Tuna Fishing

In recent decades, Japan has been responsible for taking the most bluefin tuna from the Pacific Ocean, accounting for over half the Pacific blue tuna harvest in 2015. In 2014 Japan landed more than 9,500 metric tonnes of Pacific bluefin tuna, followed by Mexico (4,800 metric tons), Korea (1,311 metric tons), Taiwan (525 metric tons), and the United States (408 metric tons). [Source: Matt Zbroinski, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The Pacific bluefin tuna harvest peaked in 1956 at over 40,000 metric tons, and averages about half of that today. According to Animal Diversity Web: Because these tuna are harvested both at spawning grounds (in Japan) and non-spawning grounds (such as the western coast of the U.S.), international agreements are in place to maintain a sufficient stock for sustainable fisheries. These agreements have not always been followed, and Craig et al. (2017) reported that although there is not a short-term threat to sustainability, this ineffectual international control will affect tuna long term. /=\

Purse seine, hook-and-line, and harpoon gear are used to catch Pacific bluefin tuna. Fishing gear used to catch bluefin tuna rarely contacts the seafloor so habitat impacts are minimal. These fishing methods are fairly selective and allow for the live release of unintentionally caught species. [Source: NOAA]

Pacific bluefin tuna are a highly valued species by recreational anglers. West Coast recreational fishing grounds primarily include offshore waters of southern California and northern Baja, and have historically included waters as far north as Monterey Bay. Commercial passenger fishing vessels and private boaters target Pacific bluefin tuna with recreational fishing gear using live bait (sardines or anchovy), casting jigs, and trolling jigs. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.

NOAA Fisheries and the Pacific Fishery Management Council and the Western Pacific Fishery Management Council manage this fishery on the West Coast and in the Pacific Islands under the Fishery Management Plan for U.S. West Coast Fisheries for Highly Migratory Species and the Fishery Ecosystem Plan for the Pelagic Fisheries of the Western Pacific, respectively.

Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Fishing

ensnared tuna The U.S. catch comprises about half of the total western Atlantic bluefin tuna catch and less than 10 percent of Atlantic-wide bluefin tuna catch (including the Mediterranean Sea). In 2021, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Western Atlantic bluefin tuna totaled 1 million kilograms (2.2 million pounds) and were valued at $11.7 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. Ex-vessel prices depend on a number of factors, including the quality of the fish (such as, freshness, fat content, method of storage), the weight of the fish, the supply of fish, and consumer demand. Exports vary from year to year. The majority of exported U.S. Atlantic Bluefin tuna catch is sent to sushi markets in Japan. Exports of Atlantic bluefin tuna generally depend on the amount of commercial landings and Japanese yen/U.S. dollar exchange rates. [Source: NOAA]

U.S. fishermen harvest bluefin tuna with handgear (rod-and-reel, handline, and harpoon) and purse seines. Although fishermen are not allowed to use pelagic longline gear in the United States to target bluefin tuna directly, regulations allow them to retain a limited number of bluefin tuna caught incidentally while fishing for other species such as swordfish and yellowfin tuna. Fishermen generally target schools of bluefin tuna, and their fishing gear is fairly selective and allows for the live release of any unintentionally caught species. Fishing gear used to catch bluefin tuna rarely contacts the ocean floor and therefore has minimal impact on habitat.

Among recreational anglers, bluefin tuna must be larger than 69 centimeters (27 inches) to be retained.: and can not be sold. Depending on the recreational fishery (such as, private vessels and charter/headboat vessels), limits on the amount and size of fish that fishermen can keep per fishing trip vary. All released bluefin tuna must be released without removing the fish from the water and in a manner that will maximize its survival. Recreational fishing for highly migratory species such as bluefin tuna provides significant economic benefits to coastal communities through individual angler expenditures, recreational charters, tournaments, and the shoreside businesses that support those activities.

Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Fishing Management

Effective conservation and management of highly migratory species like bluefin tuna require international cooperation as well as strong domestic management. NOAA Fisheries, through the Atlantic Highly Migratory Species Management Division, manages the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery in the United States, and sets regulations for the U.S. fishery based on conservation and management recommendations from the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), consistent with applicable U.S. laws.

The species are managed under the 2006 Consolidated Atlantic Highly Migratory Species Fishery Management Plan and amendments, which says commercial and recreational fishermen must have a permit to harvest bluefin tuna and sets annual quota and subquotas, gear restrictions, time-area closures and minimum size limits.Federal management for Atlantic tunas applies to state waters as well, except in Connecticut, and Mississippi. NOAA Fisheries periodically reviews these states’ regulations to make sure they’re consistent with federal regulations. Regulations do not allow targeted fishing of bluefin tuna in the Gulf of Mexico, an important spawning area for the species. NOAA Fisheries published several recent regulations that are expected to reduce and improve accounting for bluefin tuna dead discards, including gear restricted areas and individual transferable quotas in the pelagic longline fishery, modified quota category allocations, and enhanced monitoring and reporting.

ICCAT implemented harvest quotas for the western Atlantic bluefin tuna stock in 1982. Since then, catch has been relatively stable. NOAA Fisheries requires U.S. commercial fishermen who fish for yellowfin tuna, swordfish, and other species with pelagic longlines in the Gulf of Mexico to use weak hooks, a type of hook designed to reduce the incidental catch and bycatch of Atlantic bluefin tuna. Fishing for bluefin tuna in two known hotspots — Cape Hatteras, North Carolina and the Gulf of Mexico — is strictly regulated.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023