Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish

AQUACULTURE

Aquaculture is the breeding, rearing, and harvesting of fish, shellfish, algae, aquatic plants. and other organisms in all types of water environments. Basically, it’s farming in water. U.S. aquaculture is an environmentally responsible source of food and commercial products, helps to create healthier habitats, and is used to rebuild stocks of threatened or endangered species. [Source: NOAA]

Oceans cover 71 percent of Earth yet provide less than 2 percent of our food but that figure will probably increase in the future, The total first sale value of fisheries and aquaculture production of aquatic animals in 2020 was estimated at US$406 billion, of which US$265 billion came from aquaculture production.

The aquaculture industry is the fastest-growing segment of global food production. In 2021, approximately 92.6 million metric tons of fish was captured in the wild, while 85.5 million metric tons were bred, raised, and farmed through aquaculture. Ian Urbina wrote in The New Yorker: The United States imports eighty percent of its seafood, much of which is farmed. Often, it comes from China, by far the world’s largest producer, where fish are grown in sprawling landlocked pools or in offshore pens spanning several square miles. [Sources: Statista, Ian Urbina, The New Yorker, March 1, 2021]

There are two main types of aquaculture — marine and freshwater. U.S. freshwater aquaculture produces species such as catfish and trout. Freshwater aquaculture primarily takes place in ponds or other manmade systems. Marine aquaculture refers to farming species that live in the ocean and estuaries. In the United States, marine aquaculture produces numerous species including oysters, clams, mussels, shrimp, seaweeds, and fish such as salmon, black sea bass, sablefish, yellowtail, and pompano. There are many ways to farm marine shellfish, including “seeding” small shellfish on the seafloor or by growing them in bottom or floating cages. Marine fish farming is typically done in net pens in the water or in tanks on land. [Source: NOAA]

Related Articles: SEAWEED FARMING UNDER SEAWEED: FOOD, HEALTH, FARMING AND CLIMATE CHANGE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; COMMERCIAL FISHING: CONSUMPTION, DEMAND, LEADING NATIONS, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF FISHING: IN THE PREHISTORIC, ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL AND MODERN ERAS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BENEFITS OF EATING FISH AND CHOOSING THE BEST FISH TO EAT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; COMMERCIAL FISHING INDUSTRY: TECHNOLOGY, SECTORS, PROBLEMS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; TYPES OF COMMERCIAL FISHING AND NETS: TRAWLING, LONGLINES, PURSE SEINERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; OVERFISHING: CAUSES, EFFECTS AND SOLUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ILLEGAL OCEAN FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; AQUACULTURE AND FISH FARMS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CATEGORY: COMMERCIAL AND SPORT FISHING AND FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com

Aquaculture as an Alternative to Regular Fishing

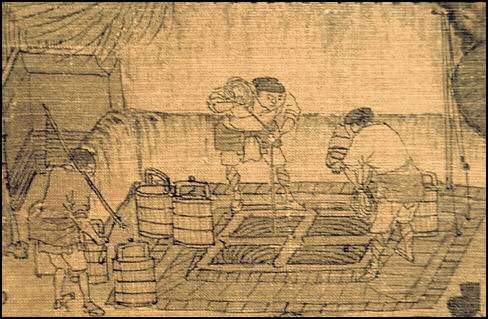

10th century fish farming in China Aquaculture is a method used to produce food and other commercial products, restore habitat and replenish wild stocks, and rebuild populations of threatened and endangered species. As the demand for seafood has increased, technology has made it possible to grow food in coastal marine waters and the open ocean.

Aquaculture has emerged as an alternative to regular fishing, which is at the root of problems like overfishing, decline in fish numbers, ocean pollution and decline of some marine species. In the fishing industry, the trend is referred to as “from capture to culture.” Ian Urbina wrote in The New Yorker: “Drawbacks aside, leading environmental groups have embraced the idea that industrial aquaculture could help feed the planet’s growing population — and the growing demand for animal protein. In a 2019 report, the Nature Conservancy argued that by 2050 sustainable fish farms should become our primary source of seafood. [Source: Ian Urbina, The New Yorker, March 1, 2021]

“Aquaculture has existed in rudimentary forms for centuries, and it does have some clear benefits over catching fish in the wild. It reduces the problem of bycatch — the thousands of tons of unwanted fish that are swept up each year by the gaping nets of industrial fishing boats, only to suffocate and be tossed back into the sea. And farming bivalves (oysters, clams, and mussels) promises a cheaper form of protein than traditional fishing for wild-caught species. In India and other parts of Asia, these farms have become a crucial source of jobs, especially for women.

Aquaculture makes it easier for wholesalers to insure that their supply chains are not indirectly supporting illegal fishing, environmental crimes, or forced labor. There’s potential for environmental benefits, too: with the right protocols, aquaculture uses less freshwater and arable land than most animal agriculture. The carbon emissions produced per pound of fish are a quarter of those produced per pound of beef, and two-thirds of those produced per pound of pork.

Expansion of Aquaculture

Fish Farm Harvesting Plant

Aquaculture production has been the main driver of the growth of total fish production since the late 1980s. In 1950, production in inland waters represented only 12 percent of the total fisheries and aquaculture production and, with some fluctuations, this share remained relatively stable until the late 1980s. Then, with the growth of aquaculture production, it gradually increased to 18 percent in the 1990s, 28 percent in the 2000s and 34 percent in the 2010s. This trend continues but at a slower rate — 3.3 percent in 2018–2019 and 2.6 percent in 2019–2020 versus an average of 4.6 percent per year during the period 2010–2018. [Source: “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022" by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)]

Worldwide fish farming grew from about 5 million tons in 1970 to 50 million tons in 2000. As of 1999, about one quarter of the fish humans ate was raised on fish farms (compared to 6.3 percent in 1970). By 2004 one third (45.47 million tons) was. Now more fish and shellfish are produced on farms than harvested in the wild. Much of the growth has been in Asia, home to 90 percent of fish farms in the 2010s. China, the world leader, imports additional fish to make fish oil, fish food, and other products.

Aquaculture expanded about 14-fold between 1980 and 2014. Joel K. Bourne, Jr. wrote in National Geographic: In 2012 its global output, from silvery salmon to homely sea cucumbers only a Chinese cook could love, reached more than 70 million tons — exceeding beef production clearly for the first time. Population growth, income growth, and seafood’s heart-healthy reputation are expected to drive up demand by 35 percent or more in just the next 20 years. With the global catch of wild fish stagnant, experts say virtually all of that new seafood will have to be farmed. “There is no way we are going to get all of the protein we need out of wild fish,” says Rosamond Naylor, a food-policy expert at Stanford University who has researched aquaculture systems. “But people are very wary that we’re going to create another feedlot industry in the ocean. So they want it to be right from the start.” [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014]

According to FAO in 2022: As aquaculture has grown faster than capture fisheries during the last two years, its share of total fisheries and aquaculture production has further increased. Of the 178 million tonnes produced in 2020, 51 percent (90 million tonnes) was from capture fisheries and 49 percent (88 million tonnes) from aquaculture. This represents a major change from the 4 percent share of aquaculture in the 1950s, 5 percent in the 1970s, 20 percent in the 1990s and 44 percent in the 2010s.

Marine and Freshwater Fishing and Aquaculture

Salmon farm in Portree Bay, Scotland Of the total production in 2020 and 2021, 63 percent (112 million tonnes) was harvested in marine waters (70 percent from capture fisheries and 30 percent from aquaculture) and 37 percent (66 million tonnes) in inland waters (83 percent from aquaculture and 17 percent from capture fisheries) (Figure 4). [Source: “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022" by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)]

The expansion of aquaculture in the last few decades has boosted the overall growth of production in inland waters. Despite this growth, capture fisheries in marine waters still represent the main source of production (44 percent of total aquatic animal production in 2020, compared with about 87 percent in the 1950–1980 period).

This general trend masks considerable variations between continents, regions and countries. In 2020, Asian countries were the main producers, accounting for 70 percent of the total fisheries and aquaculture production of aquatic animals, followed by countries in the Americas (12 percent), Europe (10 percent), Africa (7 percent) and Oceania (1 percent). Overall, total fisheries and aquaculture production has seen important increases in all the continents in the last few decades.

In 2020, China continued to be the major producer with a share of 35 percent of the total, followed by India (8 percent), Indonesia (7 percent), Viet Nam (5 percent) and Peru (3 percent). These five countries were responsible for about 58 percent of the world fisheries and aquaculture production of aquatic animals in 2020. Differences exist also in terms of the sector’s contribution to economic development. In recent decades, a growing share of total fisheries and aquaculture production has been harvested by low- and middle-income countries (from about 33 percent in the 1950s to 87 percent in 2020). In 2020, upper-middle-income countries, including China, were the main producers, responsible for 49 percent of the total production of aquatic animals, followed by lower-middle-income countries (32 percent), high-income countries (17 percent) and, finally, low-income countries (2 percent).

Leading Aquaculture Nations

World capture fisheries and aquaculture production for fish, crustaceans, molluscs, etc from 2018

Country — Aquaculture

1) China — 63,700,000

2) Indonesia — 16,600,000

3) India — 5,703,002

4) Vietnam — 3,634,531

5) Philippines — 2,200,914

6) Bangladesh — 2,203,554

7) South Korea — 1,859,220

8) Chile — 1,050,117

9) Egypt — 1,370,660

10) Norway — 1,326,216

[Source: FAO's Statistical Yearbook 2021, Wikipedia]

11) Japan — 1,067,994

12) Myanmar — 1,017,644

13) Thailand — 962,571

14) Brazil — 581,230

15) North Korea — 554,100

16) Ecuador — 451,090

17) United States — 444,369

18) Malaysia — 407,887

19) Iran — 398,129

20) Nigeria — 306,727

21) Spain — 283,831

22) Mexico — 221,328

23) Canada — 200,765

24) United Kingdom — 194,492

25) Russia — 173,840

26) Cambodia — 172,500

27) Peru — 100,187

Top ten aquaculture producers in 2004 by country (million of tons): 1) China (30.61); 2) India (2.47); 3) Vietnam (1.20); 4) Thailand (1.17); 5) Indonesia (1.05); 6) Bangladesh (0.91); 7) Japan (0.78); 8) Chile (0.67); 9) Norway (0.64); 10) United States (0.61); Other countries (5.35Total 45.47 million tons. [Source: FAO, 2006]

Top 5 fish farming countries in the 1990s (tons per year): 1) China (2,300,000); 2) India (600,000); 3) former USSR (300,000); 4) Japan (250,000); 5) Indonesia (240,000).

Fish Farming

Fish farming is a form of aquaculture. Fish farming has been around for millennia and today is the fastest-growing form of food production the world and one of the world’s fastest growing industries, boasting growth rates of 10 percent a year.

Fish pens line many rivers, lakes, and seashores. Farmers stock their ponds with fast-growing breeds of carp and tilapia and use concentrated fish feed to maximize their growth. [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014]

Fish farming is trumpeted by some as an answer to world’s overfishing problems. The most environmentally-friendly fish farms are on shore facilities with water treatment facilities. The fish rarely escape and the water can be treated. As fish stocks in the ocean decline fish farming is seen as critical to supplying an extra 40 million metric tons of seafood a year needed to keep up with demand.

Salmon, rainbow trout, tialpai and sea bream are among the most important fish farmed for the global market. Halibut and red snapper are also being raised in fish farms. Norway is a leader in raising cod in fish farms. Farming most species of fish is a difficult undertaking. Unlike salmon which hatch from nutrient-rich eggs and can be raised on industrially-produced feed, most major of ocean fish hatch from fragile, minuscule eggs and go through various growth stages in which they need specialized food. When they are adults they prefer live fish to industrial feeds.

See Separate Article SALMON FARMING: HISTORY, PROBLEMS, IMPROVEMENTS AND GM FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA FARMING: FROM EGGS, FROM WILD FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com

Top Farmed Fish

Common name(s) — Scientific name — Freshwater of Saltwater — Harvest in tonnes (1000 kilograms)

1) Grass carp — Ctenopharyngodon idella — Freshwater — 6,068,014 tonnes. China is the major producer of the grass carp, which grows quickly and requires fairly little dietary protein. Low-cost feed such as grain processing and vegetable oil extraction by-products, terrestrial grass, and aquatic weeds, allows the grass carp to be produced cheaply. This fish is mainly sold fresh, either in pieces or whole.

2) Silver carp — Hypophthalmichthys molitrix — Freshwater — 4,189,578 tonnes. A variety of Asian carp, widely cultivated with other aquaculture carp, but under pressure in its home range (China and eastern Siberia). Also called "flying fish", it is an invasive species in many countries.

3) Common carp — Cyprinus carpio — Freshwater — 3,791,913 tonnes

4) Nile tilapia — Oreochromis niloticus — Freshwater — 3,197,330 tonnes

5) Bighead carp — Hypophthalmichthys nobilis — Freshwater — 2,898,816 tonnes

6) Catla (a carp species from India) — Catla catla — Freshwater — 2,761,022 tonnes

7) Crucian carp — Carassius carassius — Freshwater — 2,451,845 tonnes

Loch Ainort fish farm, Scotland 8) Atlantic salmon — Salmo salar — Saltwater — 2,066,561 tonnes. The wild Atlantic salmon fishery is commercially dead; after extensive habitat damage and overfishing, wild fish make up only 0.5 percemt of the Atlantic salmon available in world fish markets. The rest are farmed, predominantly from aquaculture in Norway, Chile, Canada, the UK, Ireland, Faroe Islands, Russia and Tasmania in Australia.

9) Rohu (a kind of Indian carp) — Labeo rohita — Freshwater — 1,555,546 tonnes

10) Milkfish — Chanos chanos — Freshwater and Saltwater — 943,259 tonnes

11) Rainbow trout — Oncorhynchus mykiss — Freshwater — 855,982 tonnes

12) Wuchang bream — Megalobrama amblycephala — Freshwater — 705,821 tonnes

13) Black carp — Mylopharyngodon piceus — Freshwater — 495,074 tonnes

14) Northern snakehead — Channa argus — Freshwater — 480,854 tonnes

[Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2012; Wikipedia]

15) Amur catfish, Japanese common catfish — Silurus asotus — Freshwater — 413,350 tonnes

16) Mrigal carp — Cirrhinus mrigala — Freshwater — 396,476 tonnes

17) Channel catfish — Ictalurus punctatus — Freshwater — 394,179 tonnes

18) Asian swamp eel — Monopterus albus — Freshwater — 321,006 tonnes

19) Pond loach — Misgurnus anguillicaudatus — Freshwater — 294,456 tonnes

20) Iridescent shark — Pangasius hypophthalmus — Saltwater — 285,089 tonnes

21) Mandarin fish, Chinese perch — Siniperca chuatsi — Freshwater — 281,502 tonnes

22) Yellowhead catfish, Korean bullhead — Tachysurus fulvidraco — Freshwater — 256,650 tonnes

Tilapia Farming

Tilapia is one of the most commonly raised farmed fish. Tilapia is the common name for nearly a hundred species of cichlid fish that, in the wild, are mainly freshwater fish inhabiting shallow streams, ponds, rivers, and lakes, and less commonly found living in brackish water. Many species are from the Nile or Africa. Historically, they were raised in Africa, and are raised in fish farms all over the world. Tilapia has been the fourth-most consumed fish in the United States since 2002. [Source: Wikipedia]

A tilapia brood their eggs in their mouth. The eggs can be extracted for hatching at a farm. Mouth brooding — along with rapid growth, a vegetarian diet, and the ability to thrive in dense populations — helps make tilapia an easy fish to farm. The popularity of tilapia in the U.S. is due to its low price, easy preparation, and mild taste. It is also a traditionally popular food in the Philippines.

Li Sifa, a fish geneticist at Shanghai Ocean University, is regarded as the “father of tilapia” for developing a fast-growing breed that’s become the backbone of China’s tilapia industry, which produces 1.5 million tons a year, much of it for export. “I was very influenced by the green revolution in grains and rice,” he told National Geographic. “Good seeds are very important. One good variety can raise a strong industry that can feed more people. That is my duty. To make better fish, more fish, so farmers can get rich and people can have more food.” [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014]

Tilapia farming is not problem free. Joel K. Bourne, Jr. Wrote in National Geographic:“Tilapia pens in Laguna de Bay, the largest lake in the Philippines, are choked by an algal bloom they helped create. The overstocked lake produces large numbers of farmed fish, but excess nutrients trigger blooms that use up oxygen — and kill fish.

Sablefish

Sablefish (Scientific name: Anoplopoma fimbria) is a desired fish because it tastes good and can be farmed in an environmentally-friendly way. Also known as black cod, butterfish, skil, beshow, coalfish, it is brownish gray in color and is found in the wild in the U.S. off Alaska and West Coast. [Source: NOAA]

Sablefish are a deepwater species native to the Pacific Northwest. They are a tasty source of protein, rich in omega-3 fatty acids, and fetch a high price in local markets. The United States currently does not produce farmed sablefish commercially. However, with the species popularity and prized taste there is a growing interest in commercial farming. Federal and state regulations and monitoring requirements ensure that sablefish farming (as practiced in the United States) has minimal impact on the environment.

Farmed sablefish are incredibly efficient at converting feed to edible protein. Alternative feeds have been developed to reduce reliance on fish meal and fish oil from forage fish. They are spawned and raised in land-based hatcheries until large enough for transfer to net pens. Antibiotic use is strictly limited in the United States and is prescribed only on a case-by-case basis by an on-site veterinarian.

Sablefish look much like cod. They are often referred to as black cod, even though they are not actually part of the cod family. Females can grow more than one meter (3 feet) in length. Females are able to reproduce at 6 ½ years old and more than 65 centimeters (2 feet). Males are able to reproduce at age 5 and 60 kilograms (1.9 feet) in length. Female sablefish usually produce between 60,000 and 200,000 eggs. Sablefish can live to be more than 90 years old..

Cobia Farming Off Panama

Joel K. Bourne, Jr. Wrote in National Geographic: “Eight miles off the coast of Panama, Brian O’Hanlon, the 34-year-old president of Open Blue, is at the bottom of a massive, diamond-shaped fish cage, 60 feet beneath the cobalt blue surface of the Caribbean, watching 40,000 cobia do a slow, hypnotic pirouette. Unlike salmon in a commercial pen, these eight-pound youngsters have plenty of room. [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014]

As a teenager, O’Hanlon started raising red snapper in a giant tank in his parents’ basement. “Now, off Panama, he operates the largest offshore fish farm in the world. He has some 200 employees, a big hatchery onshore, and a fleet of bright orange vessels to service a dozen of the giant cages, which can hold more than a million cobia. A popular sport fish, cobia has been caught commercially only in small quantities — in the wild the fish are too solitary — but its explosive growth rate makes it popular with farmers. Like salmon, it’s full of healthy omega-3 fatty acids, and it produces a mild, buttery, white fillet. In 2013, he shipped 800 tons of cobia to high-end restaurants around the U.S. Next year he hopes to double that amount — and finally turn a profit.

“Maintenance and operating costs are high in offshore waters. Although most salmon operations are tucked in protected coves near shore, the waves over O’Hanlon’s cages can hit 20 feet or more. But all that rushing water is the point: He’s using dilution to avoid pollution and disease. Not only are his cages stocked at a fraction of the density of the typical salmon farm, but also, sitting in deep water, they’re constantly being flushed by the current and the waves. So far O’Hanlon hasn’t had to treat the cobia with antibiotics, and researchers from the University of Miami have not detected any trace of fish waste outside his pens. They suspect the diluted waste is being scavenged by undernourished plankton, since the offshore waters are nutrient poor.

“O’Hanlon is in Panama because he couldn’t get a permit to build in the U.S. Public concerns over pollution and fierce opposition from commercial fishermen have made coastal states leery of any fish farms. But O’Hanlon is convinced he’s pioneering the next big thing in aquaculture.

Fish Farms in China and Japan

Aquaculture was invented 3,000 years ago by the Chinese, using waste from silk worm farm to feed carp raised in small freshwater-pond farms. One in every three fish eaten worldwide is farm raised. And nearly 90 percent of those eaten comes from China. More farmed seafood is produced in China, India and Southeast Asia than the rest of the world combined but often the aquatic animals are raised with little concern for environmental considerations.

China is the world largest producer of farm-raised seafood, exporting billions of dollars of shrimp, catfish, tilapia, salmon and other fish, The United States imported about $2 billion of seafood products from China in 2007, almost double what it imported four years before. Both freshwater-and seawater-based fhhs farming are widely used. Many farms have a fish farm pond for raising carp. Seafood is raised in fish farms in the Bohai Gulf and other places.

See Separate Article COMMERCIAL FISHING AND FISH FARMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Japan is one of the world’s top fish farming countries. Statistics show that the aquaculture industry produced ¥409.5 billion worth of marine products in 2009. The amount of fish raised on Japanese fish farms rose from 20.8 million tons in 1994 to 33.3 million tons in 1999. [Source: Suvendrini Kakuchi, Los Angeles Times, September 4, 2010]

Yellowtail, salmon, saurel, red sea bream and fugu (puffer fish) are the main fish raised in ocean fish farms in Japan. Sometimes they are fed tuna waste solids. Fishermen in various coastal regions raise various species, including white salmon, red sea bream and yellowtail. Hokkaido's industry produces products such as scallops, sea urchin and kelp. In Mie Prefecture, farms cultivate pearls and red sea bream while farms in Kochi Prefecture raise yellowtail and other marine products.New varieties being raised include filefish, masaba (a kind of mackerel), grunt, scorpionfish and gopher fish. Eels are raised in fresh water lakes.

See Separate Article COMMERCIAL FISHING IN JAPAN: FISHING INDUSTRY, FISH FARMS AND FISHERMEN factsanddetails.com ; factsanddetails.com

Problems with Fish Farms

Farmed seafood is often raised with little concern for the environment. Fish farming depletes grain supplies and deprives fish of coastal breeding grounds. The wild stocks in many coastal areas have all but disappeared. Unconsumed feed and excrement from fish farms have been blamed for polluting coastal areas and waterways. Industrial fish farming is a big business. It can degrade the land and pollute local water and imperil local populations of fish on a large scale. The costs of saltwater aquaculture include fish kills and red tides caused by the release of phosphate-laden waste water and other kinds of pollution,

Ian Urbina wrote in The New Yorker: “When millions of fish are crowded together, they generate a lot of waste. If they’re penned in shallow coastal pools, the solid waste turns into a thick slime on the seafloor, smothering plants and animals. Nitrogen and phosphorus levels spike in surrounding waters, causing algal blooms, killing wild fish, and driving away tourists. Bred to grow faster and bigger, the farmed fish sometimes escape their enclosures and threaten indigenous species. [Source: Ian Urbina, The New Yorker, March 1, 2021]

Joel K. Bourne, Jr. Wrote in National Geographic: “The “blue revolution,” which has delivered cheap, vacuum-packed shrimp, salmon, and tilapia to grocery freezers, has brought with it many of the warts of agriculture on land: habitat destruction, water pollution, and food-safety scares. During the 1980s vast swaths of tropical mangroves were bulldozed to build farms that now produce a sizable portion of the world’s shrimp. Aquacultural pollution — a putrid cocktail of nitrogen, phosphorus, and dead fish — is now a widespread hazard in Asia, where 90 percent of farmed fish are located. The U.S. now imports 90 percent of its seafood — around 2 percent of which is inspected by the Food and Drug Administration. In 2006 and 2007 the FDA discovered numerous banned substances, including known or suspected carcinogens, in aquaculture shipments from Asia. [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014]

People opposed to fish farming include traditional fishermen, environmentalists, coastal dwellers.Disease and pollution usually limit the life of fish and shrimp farms. To keep fish alive in densely stocked pens, some Asian farmers resort to antibiotics and pesticides that are banned for use in the United States, Europe, and Japan. Farmed fish are also kept in close quarters. As a result diseases can spread quickly and overcome the resistance to disease that fish have built up and medicines combat. Fish farming deprives fish of coastal breeding grounds. The wild stocks in many coastal areas where fish farming is widely practiced have all but disappeared. Unconsumed feed and excrement from fish farms have been blamed for polluting coastal areas and waterways.

And on top of everything else farmed fish often doesn’t taste nearly as good as wild varieties. New York Times food critic Mark Bittman wrote, “farm raised tilpau, with the best feed-to-flesh conversion ratio of any animal is less desirable to many consumers, myself included than that nearly perfectly blank canvas called tofu. It seems unlikely that farm-raised striped bass will ever taste remotely like its fierce, graceful, progenitor, or that anyone who’s had fresh Alaskan sockeye can take farmed salmon seriously.”

Feeding Farmed Fish

One of the biggest challenges with fish farming is what to feed all the farmed fish. Farmed fish need to eat between three times and nine times their body weight in their short lifetimes to survive. Food constitutes roughly seventy percent of the industry’s overhead, and so far the only commercially viable form is fish meal. Large numbers of sardines, herring, menhaden and anchovies are harvested and ground up into fish-meal pellets and used as food for the farmed fish. Fish are also fed things like the trimming from poultry factories and grains. Fish farming also depletes grain supplies.

Aquaculture is getting more efficient, In 1995 it took an average of 1.04 kilograms of wild fish to produce 1 kilograms of farmed fish. By 2007 it took 0.63 kilograms of wild fish to achieve the same result according to a study in by the University of Idaho Aquaculture Research Institute. Rosamind Naylar of Stanford University told the Washington Post, “We’ve got to solve the feed problem. We’ve got to come up with an alternative that breaks the connection between aquaculture and wild fishing for forage fish. Some of the possibilities being explored by her team are corn protein and omega-3 fatty acids synthesized from algae.

Joel K. Bourne, Jr. Wrote in National Geographic: “Whether you’re raising fish in an offshore cage or in a filtered tank on land, you still have to feed them. They have one big advantage over land animals: You have to feed them a lot less. Fish need fewer calories, because they’re cold-blooded and because, living in a buoyant environment, they don’t fight gravity as much. It takes roughly a pound of feed to produce a pound of farmed fish; it takes almost two pounds of feed to produce a pound of chicken, about three for a pound of pork, and about seven for a pound of beef. As a source of animal protein that can meet the needs of nine billion people with the least demand on Earth’s resources, aquaculture — particularly for omnivores like tilapia, carp, and catfish — looks like a good bet. “Different sources of animal protein in our diet place different demands on natural resources. One measure of this is the “feed conversion ratio”: an estimate of the feed required to gain one pound of body mass. By this measure, farming salmon is about seven times more efficient than raising beef. [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014]

“But some of the farmed fish that affluent consumers love to eat have a disadvantage as well: They’re voracious carnivores. The rapid growth rate that makes cobia a good farm animal is fueled in the wild by a diet of smaller fish or crustaceans, which provide the perfect blend of nutrients — including the omega-3 fatty acids that cardiologists love. Cobia farmers such as O’Hanlon feed their fish pellets containing up to 25 percent fish meal and 5 percent fish oil, with the remainder mostly grain-based nutrients.

“In their defense, fish farmers have been getting more efficient, farming omnivorous fish like tilapia and using feeds that contain soybeans and other grains; salmon feed these days is typically no more than 10 percent fish meal. The amount of forage fish used per pound of output has fallen by roughly 80 percent from what it was 15 years ago. It could fall a lot further, says Rick Barrows, who has been developing fish feeds at his U.S. Department of Agriculture lab in Bozeman, Montana, for the past three decades. “Fish don’t require fish meal,” says Barrows. “They require nutrients. We’ve been feeding mostly vegetarian diets to rainbow trout for 12 years now. Aquaculture could get out of fish meal today if it wanted to.”

See Separate Article SALMON FARMING: HISTORY, PROBLEMS, IMPROVEMENTS AND GM FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUEFIN TUNA FARMING: FROM EGGS, FROM WILD FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com

Using Many Small Fish to Feed Large Fish

Many fish farms use feed made from large numbers of wild fish to feed a smaller number of shrimp or fish. That means a lot of smaller fish have to be caught to feed the farmed fish or another protein and food source has to be found. Large numbers of sardines, herring, menhaden and anchovies have to harvested in large numbers and ground up into pellets used as food for the farmed fish.

That means more fish have to be caught from the sea to feed the farmed fish. By even the most conservative estimated two kilograms of wild fish is necessary to produce one kilogram of farmed fish. One fourth to one third of the world’s fish catch is caught just to produce the fish oil and fish meal that fish, poultry and pig-farming operation need. Most of the fish used are anchovies, sardines and menhaden.

Paul Greenberg wrote in National Geographic, The farming or ranching of high-level predators such as salmon and which helps maintain the illusion of abundance in the marketplace. But there's a big problem with that approach: Nearly all farmed fish consume meal and oil derived from smaller fish. [Source: Paul Greenberg, National Geographic, October 2010]

Joel K. Bourne, Jr. Wrote in National Geographic: The fish meal and oil that feeds farmed fish come from forage fish like sardines and anchovies, which school in huge shoals off the Pacific coast of South America. These forage fisheries are among the largest in the world but are prone to spectacular collapses. Aquaculture’s share of the forage-fish catch has nearly doubled between 2000 and 2013, when it gobbled up nearly 70 percent of the global fish meal supply and almost 90 percent of the world’s fish oil. So hot is the market that many countries are sending ships to Antarctica to harvest more than 200,000 tons a year of tiny krill — a major food source for penguins, seals, and whales. Though much of the krill ends up in pharmaceuticals and other products, to critics of aquaculture the idea of vacuuming up the bottom of the food chain in order to churn out slabs of relatively cheap protein sounds like ecological insanity. [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014 ++]

Some fish pellets for feeding farmed fish that don't contain fish

Ian Urbina wrote in The New Yorker: “ Aquaculture farms that yield some of the most popular seafood, such as carp, salmon, or European sea bass, actually consume more fish than they ship to supermarkets and restaurants. Before it gets to market, a “ranched” tuna can eat more than fifteen times its weight in free-roaming fish that has been converted to fish meal. The result is a troubling paradox: the seafood industry is ostensibly trying to slow the rate of ocean depletion, but, by farming the fish we eat most, it’s draining the stock of many others — the ones that never make it to the aisles of Western supermarkets. Researchers have identified various potential alternative food sources — including seaweed, cassava waste, soldier-fly larvae, single-cell proteins produced by fungi and bacteria, and even human sewage — but none are being produced affordably at scale. So, for now, fish meal it is. [Source: Ian Urbina, The New Yorker, March 1, 2021]

Bourne wrote in National Geographic: “Replacing fish oil remains trickier, because it carries those prized omega-3 fatty acids. In the sea they’re made by algae, then passed up the food chain, accumulating in higher concentrations along the way. Some feed companies are already extracting omega-3s directly from algae — the process used to make omega-3 for eggs and orange juice. That has the added benefit of reducing the DDT, PCBs, and dioxins that can also accumulate in farmed fish. An even quicker fix, Stanford’s Rosamond Naylor says, would be to genetically modify canola oil to produce high levels of omega-3s. ++

Improved Fish Farms

The trend is for more fish farming in the open ocean. The United States, Japan, Taiwan, China, South Korea, Ireland and some Mediterranean and Caribbean nations are taking steps in this direction. The United States is experimenting with a variety of species including cod, Atlantic halibut, haddock, summer flounder and mussels.

Twelve-sided fish pens, 25-feet below the surface, are being used to raise snapper and cobia, two miles off shore from Puerto Rico. The advantage with such a system is that currents that carry 500 million gallons of water a day through the pens keep the pen clean and free of excess food and excrement. The disadvantage is that pen is relatively difficult to get to, being so far from shore, making feeding and maintenance difficult and expensive. Moi are raised in Hawaii in underwater pens.

There has been some discussion of using hundreds of abandoned oil and natural gas platforms in the Gulf of Mexico as supports for deep sea fish farms that raise red snapper, mahi mahi, yellow fin tuna, and flounder, The plan is backed the U.S. government but is opposed by some environmentalists who fear they could turn large areas of the sea into feedlots. Oil platforms are ideal for open sea aquaculture, The are stable and large enough to store feed and winches and cranes than can be used to hold, raise and lower the pens. Problems include damage from storms and the high cost of feed. Efforts to improve fish farming practices in the United States has lead producers to go elsewhere where the industry is not regulated.

See Salmon and Salmon Farms

Sustainable, Non-Polluting Fish Farming?

Conservationists want to see stronger oversight, better composting, and new technologies for recirculating the water in on-land pools. Some have also pushed for aquaculture farms to be located in deeper waters with faster and more diluting currents. On how to raise farmed fish without spreading disease and pollution Joel K. Bourne, Jr. wrote in National Geographic: For tilapia farmer Bill Martin, the solution is simple: raise fish in tanks on land, not in pens in a lake or the sea. “Net pens are a total goat rodeo,” says Martin, sitting in an office adorned with hunting trophies. “You’ve got sea lice, disease, escapement, and death. You compare that with a 100 percent controlled environment, possibly as close to zero impact on the oceans as we can get. If we don’t leave the oceans alone, Mother Nature is going to kick our butts big-time.” [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014]

“Martin’s fish factory, however, doesn’t leave the land and air alone, and running it isn’t cheap. To keep his fish alive, he needs a water-treatment system big enough for a small town; the electricity to power it comes from coal. Martin recirculates about 85 percent of the water in his tanks, and the rest — high in ammonia and fish waste — goes to the local sewage plant, while the voluminous solid waste heads to the landfill. To replace the lost water, he pumps half a million gallons a day from an underground aquifer. Martin’s goals are to recirculate 99 percent of the water and to produce his own low-carbon electricity by capturing methane from the waste. But those goals are still a few years away. And though Martin is convinced that recirculating systems are the future, so far only a few other companies are producing fish — including salmon, cobia, and trout — in tanks on land.

Catfish are raised in inland farms that have little impact on coastal ecosystems. America’s Catch catfish farm in Itta Bena, Mississippi produces 30 million pounds of fish each year from its 500 ponds. The fish are vegetarians: their feed is made from soy, corn, rice, wheat, and cottonseed meal, with no antibiotics. “We’re taking the high road,” says owner Solon Scott. “This is a good, sustainable source of protein.”

At an experimental farm in a fjord on Canada’s Vancouver Island giant Japanese scallops thrive on fish waste. The farm also uses sea cucumbers and kelp to consume excretions from nearby pens of native sablefish. Joel K. Bourne, Jr. wrote in National Geographic: Stephen Cross of the University of Victoria "feeds only one species — a sleek, hardy native of the North Pacific known as sablefish or black cod. Slightly down current from their pens he has placed hanging baskets full of native cockles, oysters, and scallops as well as mussels that feed on the fine organic excretions of the fish. Next to the baskets he grows long lines of sugar kelp, used in soups and sushi and also to produce bioethanol; these aquatic plants filter the water even further, converting nearly all the remaining nitrates and phosphorus to plant tissue. [Source: Joel K. Bourne, Jr., National Geographic, June 2014]

farmed sablefish

On the seafloor, 80 feet below the fish pens, sea cucumbers — considered delicacies in China and Japan — vacuum up heavier organic waste that the other species miss. Minus the sablefish, Cross says, his system could be fitted onto existing fish farms to serve as a giant water filter that would produce extra food and profit. ““Nobody gets into farmed production without wanting to make a buck,” he adds, over a plate of pan-seared sablefish and scallops the size of biscuits. “But you can’t just go volume, volume, volume. We’re going quality, diversity, and sustainability.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2023