Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish

OVERFISHING

Bluefin tuna catch By some estimates one-third of fisheries around the world are operating at unsustainable levels and 70 percent are unable to withstand more fishing. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 70 percent of the world's marine fish stocks are fully fished, overfished, depleted or recovering. more than 57 percent of all fish stocks are “maximally sustainably fished” and only 7 percent of stocks as “underfished.”

Ray Hilborn, a fisheries scientist at the University of Washington, doesn't think the situation is as bad as it is made out to be when some scientists were saying that 70 percent of the world's fisheries were overfished. He told National Geographic: "The FAO's analysis and independent work I have done suggests that the number is more like 30 percent." Increased pressure on seafood shouldn't come as a surprise, he adds, since the goal of the global fishing industry is to fully exploit fish populations, though without damaging their long-term viability. [Source: Paul Greenberg, National Geographic, October 2010, Paul Greenberg is the author of “Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food”]

According to a United Nations report in the late 2000s, 28 percent of the world's fisheries were overfished or depleted at that time. Of the 17 largest fisheries around the world, 15 were either at maximum exploitation levels or are depleting the level of their fish resource base. Joshua S. Reichert, of the Pew Charitable Trusts told National Geographic, “The oceans are suffering from a lot of things, but the one that overshadows everything else is fishing.”

Related Articles: COMMERCIAL FISHING: CONSUMPTION, DEMAND, LEADING NATIONS, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF FISHING: IN THE PREHISTORIC, ANCIENT, MEDIEVAL AND MODERN ERAS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BENEFITS OF EATING FISH AND CHOOSING THE BEST FISH TO EAT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; COMMERCIAL FISHING INDUSTRY: TECHNOLOGY, SECTORS, PROBLEMS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; TYPES OF COMMERCIAL FISHING AND NETS: TRAWLING, LONGLINES, PURSE SEINERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ILLEGAL OCEAN FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; AQUACULTURE AND FISH FARMS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CATEGORY: COMMERCIAL AND SPORT FISHING AND FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com

Books: “Saved by the Sea: A Love Story with Fish” by David Helvarg (St. Martin’s, 2010);”Managed Annihilation: An Unnatural History of the Newfoundland Cod Collapse” by Dean Bavington, (University of British Columbia; 2010); “Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food” by Paul Greenberg (Penguin Press, 2010)

Inexorable Advance of Overfishing

Paul Greenberg wrote in National Geographic, Fish harvests increased from 3 million tons in 1900 to 20 million in 1950 to a peak of 85 million tons in the 1980s. The world fish catch has been declining by millions of tons a year since 1988. In addition to targeted fish, fishing boats also catch large amounts of bycatch (unwanted fish). By some estimated 25 percent of all fish caught are bycatch. Each year between 20 to 40 million tons of mostly dead fish are thrown back in.

Overfishing has expanded from a local problem to a global one. When one area is overfished or rules are set up to ban fishing, the large fishing boats simply move somewhere else. Often times fisheries near one country are exploited to point of collapse by fishing boats from other nations. With the depletion of fish stocks near the shores, fishermen are heading more and more out to the open sea, where 64 percent of the ocean is beyond national jurisdiction. They target seamounts, oceanic ridges and deep-ocean plateaus.

Orange roughy production worldwide

Fen Montaigne wrote in National Geographic, “With many Northern Hemisphere waters fished out, commercial fleets have steamed south overexploiting once teaming fishing grounds. Off West Africa, poorly regulated fleets, both local and foreign, are wiping out fish stocks from the productive waters off of the continental shelf, depriving subsistence fishermen in Senegal, Ghana, Guinea, Angola and other countries of their families’ main source of protein. In Asia, so many boats have fished the waters of the Gulf of Thailand and the Java Sea that stocks are close to exhaustion.”

Some see the trend in sinister terms. Describing the message of the film “End of the Line”, a documentary praised as the “Inconvenient Truth” of the oceans, Frank Pope wrote in the Times of London, “Bigger, more powerful and more plentiful trawlers scrape clean every accessible patch of seabed. Companies out to please their shareholders fish only for immediate profit, exploiting every loophole to continue. Politicians paralyzed by fear, of angering the fishermen, are made complicit.”

Decline in the Number of Certain Species of Fish

Fen Montaigne wrote in National Geographic, “Popular species such as cod have plummeted from the North Sea to Georges Bank off New England. In the Mediterranean, 12 species of shark are commercially extinct, and swordfish there, which should grow as thick as a telephone pole, are now caught as juveniles and eaten when no bigger than a baseball bat. ”

According to a study by Ransom Myers and Boris Worm of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, published in Nature in 2003, 90 percent of the large predatory fish such as marlin, large cod, large sharks, tuna and swordfish have disappeared from the world’s oceans, Many have been snagged by long lines. There are worries that by reducing the species at the top of the food chain, entire marine ecosystems will be compromised. The 90 percent figure was derived looking at data from Japanese fishing boats that use long lines with 2,000 or more baited hooks. In the late 1980s about 10 out of every 100 hooks snagged a fish. By the early 2002, the figure had been reduced to about 1 per 100.

Over the years the fish catch had always increased as technology improved and more fishermen took to the oceans. But then in the late 1980s catches began to decline. The fishing industry complained about proposed regulations, pointing to their surveys that showed less drastic declines. Stocks of cod, haddock and herring have declined dramatically in the North Atlantic. Many fish whose numbers are declining are not even sough after as commercial fish; they are unintentionally caught on long lines of bottom-scouring trawls.

But according to the The New Yorker: “Estimating the health of a fish stock is a murky science. Marine researchers like to say that counting fish is like counting trees, except they’re mostly invisible — below the surface — and constantly moving. [Source: Ian Urbina, The New Yorker, March 1, 2021]

Causes of Overfishing

Purse seiners The problem of overfishing is being fueled by an increase in demand for fish that in turn is fueled by increased affluence (more people can afford fish as they become richer) and people eating fish for health reasons. More than a billion people rely on fish for protein.

People consume more than twice as much seafood as they did 50 years ago, with per capita aquatic food consumption growing from an average 9.9 kilograms to 20.2 kilograms in 2020, with global production of fish quadrupling in that time to meet the growing demand. In many ways the trend is not surprising as the world’s population has nearly quadrupled since the 1960s and people are eating more fish. In many places fish stocks are being depleted faster than they are being replaced. [Source: Martina Iginia, Earth.org. July 15 2022]

Fish that not so long ago hardly anybody wanted except the Japanese now are in high demand and cooperatives and trading companies in a number of countries are competing to acquire them, driving up their price. Higher prices create more incentives for fishermen to catch fish. Improved fishing technology and industrial-size fishing operations have dramatically increased fish catches (See Fishing).

The biggest consumers of herring, mackerel, anchovies and sardines are agriculture and aquaculture for feed for farmed fish and protein sources for pigs and cattle. In the 2000s, aquaculture alone consumed 53 percent of the world’s fish meal and 87 percent of its fish oil. On top of everything else this method is very inefficient. Approximately three kilograms of foraged fish goes into making one kilogram of farmed salmon. For cod the ratio is 5 to 1; for bluefin tuna it is 20 to 1, John Vlipe, a marine biologist at the University of Victoria in British Columbia told the New York Times.

Despite plummeting fish stocks overfishing has accelerated around the globe, encouraged in part by $30 billion in annual subsidies for fishing boats, fuel and other assistance, with the biggest subsidies found in Asia and Europe. Poor regulation and monitoring are serious problems. Fishing boats routinely report false data on their catches. Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, Russian and Spanish vessels have all been involved in overfishing. Researchers also blame drops on the levels of zooplankton (caused perhaps by global warming), overfishing and damage to coastal wetlands where young fish develop.

Overfishing Increasing as Global Consumption of Fish Increases

Chilean purse seine catch More than a third of the fish stocks around the world are being overfished and the problem is particularly acute in developing countries, the FAO said in a report issued in June 2020. The FAO said that tackling the issue would require several measures including stronger political will and improved monitoring as fish stocks in areas with less-developed management were in poor shape. "While developed countries are improving the way they manage their fisheries, developing countries face a worsening situation," the FAO said. [Source: Reuters, June 8, 2020]

“In 2017, 34.2 percent of the fish stocks of the world's marine fisheries were classified as overfished, a "continuous increasing trend" since 1974 when it stood at just 10 percent. Overfishing depletes stocks at a rate that the species cannot replenish and so leads to lower fish populations and reduced future production. The FAO said less intense management was common in many developing nations and was fuelled partly by limited management and governance capacities. "We notice that sustainability is particularly difficult in places where hunger, poverty and conflict exist, but there is no alternative to sustainable solutions," the agency said.

“Worldwide per capita fish consumption set a new record of 20.5 kilograms per year in 2018 and has risen by an average rate of 3.1 percent since 1961, outpacing all other animal proteins. Fish consumption accounts for a sixth of the global population's intake of animal proteins, and more than half in countries such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, the Gambia, Ghana, Indonesia, Sierra Leone and Sri Lanka.

“The FAO projected global per capita consumption would climb to 21.5 kilograms by 2030, a slowdown in the average annual growth rate to 0.4 percent, with a decline expected in Africa. "The main reason for this decline is the growth of Africa's population outpacing the growth in supply. Increasing domestic production and higher fish imports will not be sufficient to meet the region's growing demand," the FAO said. The report is based on information gathered before the COVID-19 outbreak which has led to a decline in global fishing activity as a result of restrictions and labour shortages due to the health emergency, the FAO said.

World Is Running out of Places to Catch Wild Fish, Study Finds

Paul Greenberg wrote in National Geographic, “Humanity's demand for seafood has now driven fishing fleets into every virgin fishing ground in the world. There are no new grounds left to exploit. But even this isn't enough. An unprecedented buildup of fishing capacity threatens to outstrip seafood supplies in all fishing grounds, old and new. A report by the World Bank and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations recently concluded that the ocean doesn't have nearly enough fish left to support the current onslaught. Indeed, the report suggests that even if we had half as many boats, hooks, and nets as we do now, we would still end up catching too many fish. [Source: Paul Greenberg, National Geographic, October 2010]

longliners Juliet Eilperin wrote in the Washington Post: “Global fisheries have expanded so rapidly over the past half-century that the world is running out of places to catch wild fish, according to a study conducted by researchers in Canada, the United States and Australia. The findings, published in the online journal PLoS ONE, are the first to examine how marine fisheries have expanded over time. Looking at fleets' movements between 1950 and 2005, the five researchers charted how fishing has been expanding southward into less exploited seas at roughly one degree latitude each year to compensate for the fact that humans have depleted fish stocks closer to shore in the Northern Hemisphere. [Source: Juliet Eilperin, Washington Post, December 2, 2010]

During that same period the world's fish catch increased fivefold from 19 million metric tons in 1950 to a peak of 90 million in the late 1980s, before declining to 87 million tons in 2005. It was 79.5 million tons in 2008, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, the most recent year for which figures are available.

Daniel Pauly, a co-author who serves as principal investigator of the Sea Around Us Project at the University of British Columbia Fisheries Centre, said the global seafood catch is dropping "because there's essentially nowhere to go." The fact that fish catches rose for so many decades "looks like sustainability but it is actually expansion driven. That is frightening, because the accounting is coming now." The authors - including lead author Wilf Swartz, who is a doctoral student at the university, and National Geographic Society ocean fellow Enric Sala - write that this relentless pursuit for seafood has left "only unproductive waters of high seas, and relatively inaccessible waters in the Arctic and Antarctic as the last remaining 'frontiers.' " "The focus should move from looking for something new to looking at what we have and making the most sustainable use out of it," Swartz said.

Effects of Overfishing

Overfishing has dramatic consequences not just the fish populations but also for ecosystems and human life. Scientists warn that declines in large fish species could cause many fishermen to lose their jobs, deprive the world of an important source or protein and nutrition and throw marine ecosystems out of balance. Numerous communities around the globe rely on fishing as their primary protein source and employment and income. The result of overfishing for fishermen is that they have to work harder and longer hours and sail farther to catch fewer fish. Millions of poor are deprived of an important protein source.

ensnared tuna The disappearance of large predators could throw entire marine ecosystem out of whack in ways that people had not anticipated. Fish are and the food chain they maintain are essential for eating up algae and keeping microbes in check. According to a report by the International Programme on the State of the Ocean (IPSO) the harvesting up to 90 percent of some species of big fish and sharks, meanwhile, has hugely disrupted food chains throughout the ocean, leading to explosive and imbalanced growth of algae, jellyfish and other "opportunistic" flora and fauna.

In some cases if one large predator is overfished other large predators step in to fill in the gap but then these species too are overfished and before long populations of all large predators are decimated either by overfishing or accidental catching in efforts to catch large valuable species. The decline of the size of fish also means that the fish are not living as long as they used to. This phenomena, known to biologists as “juvenescence,” may inhibit the ability of these species to reproduce and survive in significant numbers in the future. There is also evidence of declines in the numbers of so-called forage fish such as herring, mackerel, anchovies and sardines. The decline is critical for both upper food chain and many poor and not so poor people around the globe that eat them.

Overfishing may produce more harmful algal blooms. Many fish eat algae and keep its growth in check. With decreasing fish populations, algae could become more prevalent. An increased amount of algae may threaten fish populations, reefs, and overall ocean health. We’ve all seen the harmful impacts algae blooms and red tides on aquatic plants and animals. [Source: Jane Marsh, Environment.co, October 4, 2019]

Effects of Overfishing on Ocean’s Predatory Fish

Analysis of more than 200 ecological systems studied since 1880 by a team led by Villy Christensen of University of British Columbia's Fisheries Centre shows that a decrease of than 54 percent in the catch of large predator fish took place between 1960 and 2000. "It's a question of how many people are fishing, how they are fishing, and where they are fishing," Christensen said. A majority of the catch, and now of the decline, involves East Asia, which has witnessed dramatic overall economic growth.

Marc Kaufman wrote in the Washington Post, “Over the past 100 years, some two-thirds of the large predator fish in the ocean have been caught and consumed by humans, and in the decades ahead the rest are likely to perish, too. In their place, small fish such as sardines and anchovies are flourishing in the absence of the tuna, grouper and cod that traditionally feed on them, creating an ecological imbalance that experts say will forever change the oceans.[Source: Marc Kaufman, Washington Post, February 20, 2011]

mako shark "Think of it like the Serengeti, with lions and the antelopes they feed on,"Villy Christensen of University of British Columbia's Fisheries Centre told the Washington Post. "When all the lions are gone, there will be antelopes everywhere. Our oceans are losing their lions and pretty soon will have nothing but antelopes." On the cause, Christensen said, "It's a question of how many people are fishing, how they are fishing, and where they are fishing." A majority of the catch, and now of the decline, involves East Asia, which has witnessed dramatic overall economic growth.

In describing the likely explosion of small fish, Christensen's team differed with a 2006 report in the journal Science that warned of an ocean without fish for humans by mid-century. But they say that absent predators, the fisheries will be out of balance and more subject to mass die-offs from disease and from boom-and-bust cycles that, over time, can lead to algae or bacteria blooms that take the oxygen out of the waters and make them uninhabitable.

Forty Fish Species in the Mediterranean May Become Extinct

AP reported in April 2011, “A new study suggests that more than 40 fish species in the Mediterranean could vanish in the next few years. The study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) says almost half of the species of sharks and rays in the Mediterranean and at least 12 species of bony fish are threatened with extinction due to overfishing, pollution and the loss of habitat.” [Source: John Heilrpin, AP, April 18, 2011]

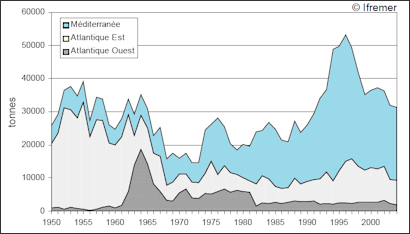

Commercial catches of bluefin tuna, sea bass, hake and dusky grouper are particularly threatened, said the study by the Swiss-based IUCN, an environmental network of 1,000 groups in 160 nations. "The Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic population of the Atlantic bluefin tuna is of particular concern," said Kent Carpenter, IUCN's global marine species assessment coordinator. He cited a steep drop in the giant fish's reproductive capacity due to four decades of intensive overfishing. Japanese diners consume 80 percent of the Atlantic and Pacific bluefins caught and the two tuna species are especially prized by sushi lovers.

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization says fish stocks continue to dwindle globally despite increasing efforts to regulate catches and stop overfishing. Fishing in the Mediterranean is regulated by U.N. treaties, the European Union and separate laws among the 21 nations that border the sea. The IUCN study, which began in 2007 and included 25 marine scientists, is the first time the group has tried to assess native marine fish species in an entire sea.

The study blames the use of highly effective trawlers and driftnets for the incidental capture and killing of hundreds of marine animals with no commercial value. But it also concluded there's not enough information to properly assess almost one-third of the Mediterranean's fish. "Even though marine resources in the Mediterranean Sea have been exploited for thousands of years and are relatively well studied, the data deficient group may in fact include a large proportion of threatened fishes," the study said, calling for more research.

Combating Overfishing

A number of international agreements on oceans and fisheries have been signed. At the Johannesburg Earth Summit in 2003, for example, participants agreed to aim to restore fish stocks to sustainable levels by 2015. Many large fishing boats are required to take a biologist along to make sure they are respecting international fishing laws. Commercial fishers have resisted quota and moratoriums. Many of agreements are difficult to enforce and lack penalties that could truly serve as deterrents.

Factory fishing ship

Paul Greenberg wrote in National Geographic, “Conservation biologists now believe that suggestions must be transformed into obligations. If treaties can establish seafood-consumption targets for every nation, they argue, citizens could hold their governments responsible for meeting those targets. Comparable strategies have worked to great effect in terrestrial ecosystems, for trade items such as furs or ivory. The ocean deserves a similar effort, they say.

Restoration plans have been adopted for troubled fish stocks and some fisheries are rebounding. Fish stocks can be resilient. Some overfished areas have rebounded in a relatively short period of time. In 1994, after fisheries collapsed in the Georges Bank in the Gulf of Maine, groundfish fishing and dragging for scalloped was banned in three areas that together encompassed more than 17,200 square kilometers. Within five years haddock and flounder stocks had rebounded and scallops were bigger and became nine to 14 times more dense than in fished areas. Places where cod and swordfish were once king fishermen now make a living catching snow crabs and lobster, whose populations have increased.

Solutions to Overfishing

Many scientists and conservationists says that several urgent things have to be done if the world’s oceanic fish are to stand a chance of surviving in healthy numbers. They include: 1) the ocean needs to be seen as an ecosystem, with all of its components addressed, and not seen as an endless supplier of marine life for modern technology to exploit. 2) The management councils that oversees fisheries, need to include more scientists and conservationists among their members not just representatives of the fishing industry. 3) Tough quotas have to be set and enforced. 4) And perhaps the most important thing of all is that the number of fishing boats has to be limited. For the overfishing problem to be really be addressed the sustainability movement has to catch on Asia. More than two thirds of the world’s seafood is consumed in China, Japan and other parts of Asia and boats from China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Russia pull in some of the the largest catches, much of it undocumented. On concrete actions that can be takenm Martina Iginia of Earth.org wrote:

1) Ban Fishing Subsidies: Subsidies for fuel, fishing gear, and building new vessels notoriously incentivise overfishing and represent thus a huge problem. They often benefit large-scale fishing companies which indirectly encourage the use of fuel-intensive fishing and destructive fishing practices such as deep-sea trawling. Furthermore, researchers found that illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is sometimes related to more serious problems like human trafficking and slavery at sea. [Source: Martina Iginia, Earth.org. July 15 2022]

Russian factory fishing ship

In June 2022, the World Trade Organization (WTO) secured a historic deal aimed at curbing fishing subsidies and reducing global overfishing. The landmark Fisheries Agreement introduces new rules to help preserve the world’s oceans, boost falling fishing stocks, and protect the countless communities around the world whose livelihoods depend on marine resources. The accord will see countries working together to ban subsidies to IUU fishing and restrict subsidies for stocks that are already overfished. The text allows for subsidies as long as they are implemented to rebuild the fishing stock to a “biologically sustainable level” and it includes measures to enhance transparency and accountability of governments on how they subsidise the industry.

2) Adopt Rights-Based Fishery Management: A much needed solution to overfishing is the adoption of rights-based fishery management tools. According to the World Wildlife (WWF), such approach can transform global fisheries performance and help achieve a balance between economic, ecological, and social needs around the world. In short, rights-based management (RBM) entitles an entity — such as a person, community, company, or fishing vessel — to fish in a particular place at a particular time. While guaranteeing such entities a certain portion of the catch, they are also required to adhere to certain limits, which range from a limit on how much fish they can catch to specific timeframes and seasons in which fishing is allowed.

One of the most effective policies to reduce overfishing are catch-share programmes, which give out harvest allowances to individuals or companies. These not only help incentivise smarter and timelier fishing rather than a race to catch as much as stock possible but they also promote a healthy balance between the needs of people, the ocean, and the economy and can guarantee healthier fish populations.

3) Apply Regulations on Fishing Nets: By-catching refers to the event of unwanted marine animal species being caught in fisher’s nets as a byproduct, a practice that has increased tremendously since overfishing became such a huge issue. The gigantic nets trawled around the world’s oceans everyday catch thousands of untargeted marine species, including sea turtles, birds and sharks. To tackle this issue, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) implemented a simple solution: placing the top end of the nets two meters lower, a move that has been shown to effectively reduce the mortality of marine mammal bycatch by 98 percent in places like the Indian Ocean. This and other regulations aimed at preventing or discouraging by-catch will help keep the environments that fishers work in healthy.

4) Protect Essential Predator Species: Sharks and tuna are some of the marine animal species most prone to overfishing. Labeled as essential predators, these animals lay a vital role in maintaining local ecosystems. Without them, issues such as overpopulation, algal bloom, and other serious environmental problems would arise. For this reason, one of the best solutions to overfishing is promoting programmes and policies that protect these vulnerable species from being caught by fishing vessels. 90 percent of blue sharks, for example, are mistakenly caught by fishers every year despite not being commercially valuable. It is estimated that one-third of shark species face extinction because of overfishing, bycatch, pollution, and habitat loss. The FAO has successfully launched a programme to protect threatened deep-sea marine life by supporting new assessment protocols in designated areas before any fishing activities can begin.

Russian factory fishing ship

5) Increase Marine Protected Areas and Enhance Controls: Based on current UN estimates, there are more than 15,000 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the world, comprising approximately 27 million square kilometers (almost 10.6 million square miles) — or nearly 7.5 percent of the ocean, an area the size of North America. In such areas, tight regulations restrict or often prohibit commercial fishing and other potentially harmful activities altogether. However, experts believe that governments around the world should put more effort in expanding MPAs — given that 92 percent of the world’s oceans are still unprotected. This is arguably one of the most effective solutions to overfishing and could contribute greatly to meeting the IUNC recommendation of protecting at least 30 percent of the ocean by 2030.

6) Require Traceability Standards: Among the best solutions to overfishing is also the introduction of traceability standards. As it was highlighted in the 2022 State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture Report, traceability systems represent a crucial effort toward transparent and responsible value chains. Having such standards in place would “allow a product to be followed from its origin to the end market, informing about compliance with many fisheries regulations as well as food safety and certification requirements.” Traceability standards have been ensured in the past through the adoption of so-called catch documentation schemes (CDS), issuing certificates and trade documents validated by trustworthy national authorities to establish whether a product has been legally sourced, and certifying that the catch was sourced in compliance with all applicable requirements. FAO has been constantly working to support national authorities in understanding and implementing these schemes.

7) Impose A Ban on Fishing in International Waters: According to Our World In Data, 99 percent of international waters that do not belong to any single country — also called ‘high seas’ — are unprotected. Given the effectiveness of protected waters in saving fish population and the current lack of regulation of fishing in international waters, introducing a ban on fishing in open seas would likely be an extremely effective overfishing solution. In 2017, nine nations including Japan, China, and South Korea as well as the European Union agreed on a historic deal to place the central Arctic Ocean (CAO) — an area of nearly 3 million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles) — off-limits to commercial fishers for at least the next 16 years. Moreover, the FAO launched the Common Oceans Program, a plan to regulate fishing in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), which comprise 40 percent of the planet’s surface. The programme successfully reduced tuna overfishing and banned fishing from critically vulnerable areas.

Replacing Wild Fish with Aquaculture

In “Four Fish,” Paul Greenberg argues that the salvation of wild fish lies in farmed ones, though not in the kind you’ll find on ice at Stop & Shop. (Today, most farmed fish are fed on wild-caught fish, a practice that only exacerbates the problem.) Greenberg is a believer in what’s sometimes called “smart aquaculture,” and thinks we should be eating species like Pangasius hypophthalmus, commonly known as tra. Tra happily feed on human waste and were originally kept in Southeast Asia to dispose of the contents of outhouses. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, August 2, 2010]

Replacing wild fish altogether would not be easy, Gibbons noted. Ray Hilborn, a University of Washington professor of aquatic and fishery sciences, recently estimated that switching from wild fish to an equivalent amount of animal protein from pigs, cattle and chickens could take land resources equal to 22 times the existing rainforest. [Source: Juliet Eilperin, Washington Post, December 2, 2010]

Alaska Ranger side layout

Quotas and Reducing the Number of Fishing Boats

Jacqueline Alder from the U.N. Environment Program suggested that the number of fishing boats and days they fish have to be restricted. "If we can do this immediately, we will see a decline in fish catches. However, that will give an opportunity for the fish stocks to rebuild and expand their populations," she said. Daniel Pauly, a fisheries scientist at the University of British Columbia, suggests reducing the world's fishing fleets by 50 percent, establishing large no-catch zones, limiting the use of wild fish as feed in fish-farming. In no-catch-zones, Enric Sala, a National Geographic fellow, "Barely one percent of the ocean is now protected, compared with 12 percent of the land," Enric Sala adds, "and only a fraction of that is fully protected." Unfortunately, the seafood industry and some national government have blocked efforts to make reforms.

On the issue of limiting the number of fishing boats and keeping a close watch on what fishermen catch, governments can help out by buying out fishing boats and licences, creating economic incentives for some to quit fishing, and adopting better monitoring procedures. But even if measures are widely adopted by regulated vessels there are large numbers of illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) vessels out there that skirt the rules and answer to no one.

Improvements in fishing methods have reduced bycatch by up to 60 percent and dramatically reduced the number of endangered birds such as albatrosses that are caught in fishing lines. Measures such as closing seasons, closing areas or limiting access often do not work because fishing vessels are so efficient so they can take in the amount of fish normally taken in by several vessels.

Marine Reserves

Some have proposed that huge swaths of the sea be set aside as so-called “marine protected areas,” or M.P.A.s, where most commercial activity would be prohibited.

Setting up marine reserves is seen as major means of saving the world’s oceans. In 2009, in the closing weeks of his term, U.S. President George W. Bush, who was not well known for his environmental record, established the largest marine conservation area in U.S. history when he declared a 505,800 kilometer protected area in Pacific Ocean that included the Mariana Trench , and areas around islands in Marianas, Samoa and near the equator. In 2006, he also created the largest marine reserve in the world — the Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, a 138,000-square-mile reserve in an area of unspoiled reefs and shoals neat the Hawaiian Islands. The area covers an area larger than all the national parks in the United States combined.

Scientists have called for the creation of a network of marine parks and protecting more ocean areas. Only 0.5 percent of the oceans are protected, compared to about 12 percent of the Earth’s land area. Most protected areas are close to shore such as the Great Barrier Reef, waters around the Galapagos Islands or places in the Mediterranean.

Catch Shares and Quotas

Michael Weber, the author of “From Abundance to Scarcity,” is encouraged by the introduction of new regulatory mechanisms such as “individual transferable quotas,” or I.T.Q.s. The idea behind I.T.Q.s is that if fishermen are granted a marketable stake in the catch they will have a greater economic interest in preserving it. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, August 2, 2010]

Many believe the solution to the overfishing problem is establishing overall catch quotas and allow people to buy and sell their fishing rights. A regulatory scheme known as “catch shares” allows fishermen to own shares in a fishery — that is, the right to catch a certain percentage of a scientifically determined sustainable harvest. Fishermen can buy or sell shares, but the number of fish caught in a given year is fixed. The method has worked well with lobsters in Australia and made lobstermen there very rich. It has also worked very well in Alaska. A study published in Science estimated that if catch shares were put in place in 1970 only 9 percent of the world’s fisheries would have collapsed rather than 27 percent as had occurred by 2003.

Alaska’s fishing industry regulation scheme has become a model for sustainable fishing. Each year during the salmon spawning human fish counters take up positions along the major salmon rivers, spotter planes track the migration of the fish, patrols ward of aggressive bears and the first hint that there is a decline in number of fish the entire fishing season is put in hold and fishermen are ordered to pull in their nets. Fishermen are eager to cooperate. The system was put in place after Alaskans learned their lesson about killing their goose with the golden egg when salmon fisheries collapse as a result of overfishing in the 1950s.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2023