Home | Category: Ocean Environmental Issues

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF HOTTER OCEANS

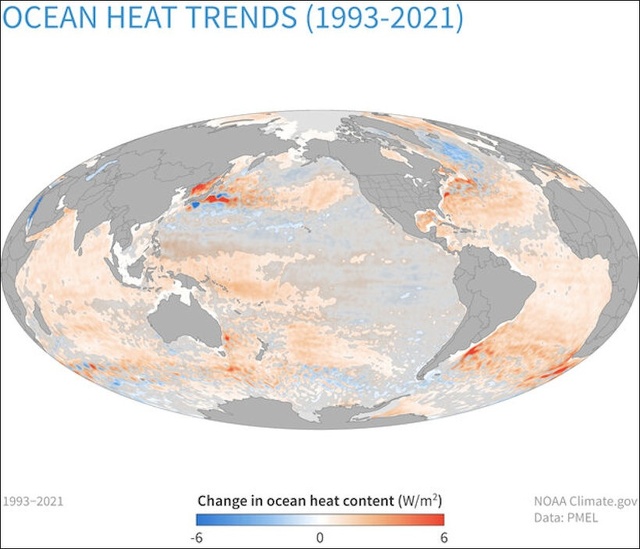

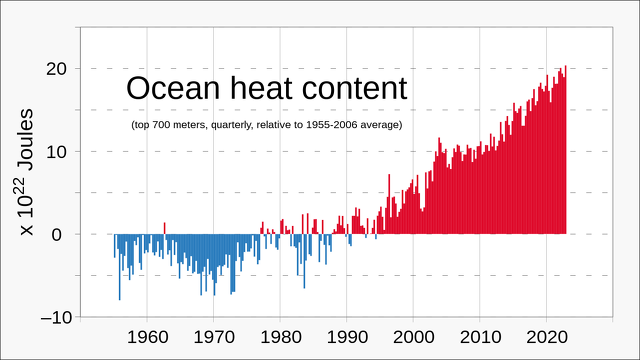

The oceans have absorbed about 90 percent of the excess heat produced by global warming, raising average ocean temperatures by roughly 1.8°F (1°C) over the past century, according to NASA. This accumulation of heat has driven a 50 percent increase in surface marine heat waves in just the last decade. [Source: Oliver Milman, The Guardian, January 11, 2022; The Hill, February 2, 2022; Dinah Voyles Pulver, USA TODAY, July 5, 2023; Victor Tangermann, Futurism, May 4, 2023]

Research from the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado shows that warmer waters are intensifying storms, hurricanes, and extreme rainfall, amplifying the risk of catastrophic flooding. As seawater expands with heat and erodes the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets—now shedding roughly a trillion tons of ice each year—global sea levels continue to rise.

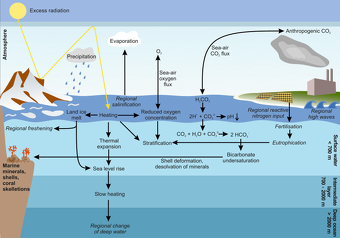

When oceans absorb carbon dioxide, they grow more acidic, damaging coral reefs that support a quarter of all marine species and provide food for more than 500 million people. Ocean acidification also harms seagrass meadows, kelp forests, and certain fish species. Long-term warming has been strongest in the Atlantic and Southern oceans, while the North Pacific has experienced a “dramatic” rise in temperature since 1990. The Mediterranean Sea set a clear high-temperature record in 2021.

The oceans have absorbed most of the excess heat generated by fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, and other human activities over the past 50 years—temporarily sparing land-dwelling species from even more dangerous temperatures. But this protection has limits. Kyle Van Houtan of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, lead author of a 2022 PLOS Climate study, said: “Today, the majority of the ocean’s surface has warmed to temperatures that only a century ago occurred as rare, once-in-50-year extreme warming events.” Extreme heat is now the norm across much of the global ocean, weakening ecosystems that once buffered coasts from severe storms and served as critical carbon sinks.

Exceptionally warm Atlantic waters could energize more hurricanes, though in some years El Niño’s strong wind shear may suppress activity. Marine heat waves—defined as periods when ocean temperatures fall within the warmest 10 percent for a region and time of year—are becoming both more frequent and more severe. Their impacts can be devastating: “the Blob” (2014–2016) fueled harmful algal blooms, wiped out kelp forests, closed fisheries with $185 million in losses, killed an estimated one million seabirds, and reduced Gulf of Alaska cod stocks by up to 70 percent.

At the poles, Antarctic sea ice has collapsed to record lows—nearly 1 million square miles below the long-term June average in 2023 —marking a sharp reversal after decades of modest growth. Since 2016, Antarctic ice coverage has stayed consistently below normal, with historic lows in both 2022 and 2023. Scientists link this rapid decline to atmospheric and oceanic feedbacks, including unusually warm Southern Ocean waters and storm-driven winds that impede ice formation.

Related Articles:

GLOBAL WARMING AND THE SEA factsanddetails.com

OCEAN ACIDIFICATION ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ENDANGERED CORAL REEFS AND THEIR RECOVERY AND REBIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com

GLOBAL WARMING AND CORAL REEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CORAL BLEACHING: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND RECOVERY ioa.factsanddetails.com

HUMANS AND THE OCEANS: MYTHS, PRODUCTS, ETIQUETTE AND DRUGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

POLLUTION IN THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

RED TIDES (HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS): DEAD ZONES, EUTROPHICATION, CAUSES AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Climate and the Oceans” (Princeton Primers in Climate) by Geoffrey K. Vallis Amazon.com

“The Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate Change: A Complete Visual Guide”

by Juliane L. Fry, Hans-F Graf, et al. Amazon.com

“Atmosphere, Ocean and Climate Dynamics: An Introductory Text” (International Geophysics by John Marshall, R. Alan Plumb Amazon.com

“Great Ocean Conveyor: Discovering the Trigger for Abrupt Climate Change”

by Wally Broecker Amazon.com

“Beyond Extinction: The Eternal Ocean―Climate Change & the Continuity of Life”

by Wolfgang Grulke Amazon.com

“The Unnatural History of the Sea” by Callum Roberts (Island Press (2009) Amazon.com

“The Ocean of Life: The Fate of Man and the Sea” by Callum Roberts Amazon.com

“Plastic Soup: An Atlas of Ocean Pollution” by Michiel Roscam Abbing Amazon.com

“Blue Hope: Exploring and Caring for Earth's Magnificent Ocean” by Sylvia Earle (2014) Amazon.com

“The Empty Ocean” by Richard Ellis (2003) Amazon.com

“Oceans: The Threats to Our Seas and What You Can Do to Turn the Tide” by , Jon Bowermaster (2010) Amazon.com

“Dark Side of The Ocean: The Destruction of Our Seas, Why It Maters, and What We Can Do About It” by Albert Bates Amazon.com

“Ocean's End: Travels Through Endangered Seas” (2001)

by Colin Woodard Amazon.com

“The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works” by Helen Czerski, explains how the ocean influences our world and how it functions. Amazon.com

“The Science of the Ocean: The Secrets of the Seas Revealed” by DK (2020) Amazon.com

“Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics: Fundamentals and Large-Scale Circulation” by Geoffrey K. Vallis (2006) Amazon.com

“Essentials of Oceanography” by Alam Trujillo and Harold Thurman Amazon.com

“Ocean: The World's Last Wilderness Revealed” by Robert Dinwiddie , Philip Eales, et al. (2008) Amazon.com

Heat Waves Reaching the Deep Ocean Floor

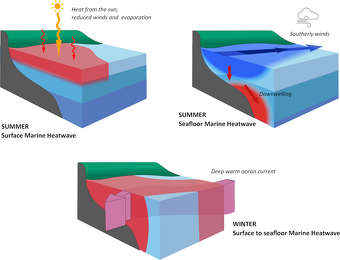

Heat waves are now penetrating the deepest parts of Earth’s oceans—and that spells trouble for the creatures that live on the seafloor. A study published March 13, 2023 in Nature Communications, shows that “bottom marine heat waves” are forming beneath the surface. These deep-water events can be especially destructive because they last longer than surface heat waves and affect species such as lobster, scallop, flounder, and cod. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, March 25, 2023]

Scientists have long known that spikes in surface temperatures can destabilize marine ecosystems. From 2013 to 2016, for example, a mass of unusually warm water known as “the blob” heated the Pacific Ocean along North America’s coast and caused the deaths of roughly 1 million seabirds after their fish prey collapsed.

Now, researchers say similar disruptions are unfolding far below. The resultsshow that bottom heat waves are occurring around the world. “This is a global phenomenon,” lead author Dillon Amaya of NOAA’s Physical Science Laboratory told Live Science. “We’re seeing bottom marine heat waves near Australia, in the Mediterranean, and in the Tasman Sea. This isn’t unique to North America.”

Until now, scientists had little understanding of how temperature spikes at the surface translate to the seafloor. To investigate, the team used existing ocean measurements to model atmospheric conditions and currents, filling in gaps for hard-to-study seafloor environments—areas that support many commercially valuable species. They found that along North America’s continental shelves, bottom heat waves lasted longer than surface heat waves. In some shallow regions, heat waves occurred simultaneously at the surface and seafloor, where different water layers mix more easily. Warm bottom waters have already been linked to coral bleaching and the spread of invasive lionfish, the researchers noted.

Predicting when and where bottom heat waves will strike remains difficult, but scientists have ideas about what drives them. One likely factor is shifting ocean currents. “For example, on the U.S. East Coast, variability in the Gulf Stream—a warm current—can absolutely change bottom temperatures,” Amaya said. Upwelling, the rise of cold, nutrient-rich water from the depths, may also play a role. Along the U.S. West Coast, changes in upwelling intensity can alter subsurface temperatures across the continental shelf.

Are Oceans Changing Color Because of Climate Change?

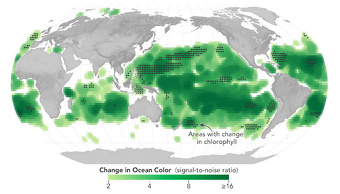

In the 2000s and 2010s vast stretches of the world’s oceans subtly shifted in color, with tropical waters in particular taking on a greener hue. Research published in Nature on July 12, 2013 shows that more than half of Earth’s oceans—an area larger than all the planet’s land combined—have changed color in ways that cannot be explained by natural variability. Scientists say the trend points strongly to the influence of human-driven climate change on marine ecosystems. [Source: Kelly MacNamara, AFP, July 13, 2023, Jack Guy, CNN, July 13, 2023]

The color of the ocean, seen from space, offers a window into life in its upper layers. Deep blue typically signals low biological activity. Greener waters indicate more phytoplankton—tiny, plant-like microbes containing chlorophyll that form the foundation of the marine food web and help stabilize Earth’s atmosphere by producing oxygen and absorbing carbon. “The reason we care about color changes is because color reflects the state of the ecosystem,” lead author B.B. Cael of the UK’s National Oceanography Centre told AFP. “Color changes mean ecosystem changes.”

Previous studies suggested that at least 30 years of chlorophyll measurements would be necessary to see clear trends, due to large year-to-year fluctuations. The new study, published in Nature, takes a broader approach. Researchers analyzed seven narrow bands of ocean color captured by NASA’s MODIS-Aqua satellite between 2002 and 2022—subtle spectral shifts invisible to the human eye.

They identified a clear, long-term trend emerging from the natural variability. When the team compared real-world observations to climate-change simulations, the match was striking: the color shifts aligned almost exactly with what models predicted would happen as greenhouse gases warmed the planet. “I’ve been running simulations for years showing that these changes in ocean color were coming,” said co-author Stephanie Dutkiewicz of MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. “To actually see it happening is not surprising—but frightening. These changes are consistent with human-induced climate change.”

To detect the trend, researchers monitored how much green versus blue light is reflected off the sea surface, using nearly two decades of Aqua satellite data. They then ran climate models to simulate ocean color with and without human-generated greenhouse gas emissions. The observed changes matched the scenario with added emissions—showing roughly 50 to 56 percent of the oceans shifting in color.

Meaning of the Changing Ocean Colors

Tropical oceans have become especially green, reflecting shifts in their ecosystems. While it’s not yet clear exactly how phytoplankton communities are changing, Dutkiewicz says the balance will vary by region: some areas may gain phytoplankton, others may lose them, and the species composition is likely changing everywhere. Because ocean ecosystems are finely tuned, any shift at the plankton level reverberates upward through krill, fish, seabirds, and marine mammals. It may also alter the ocean’s ability to store carbon, since different types of plankton absorb carbon at different rates. [Source: Kelly MacNamara, AFP, July 13, 2023, Jack Guy, CNN, July 13, 2023]

Neel V. Patel wrote in The Daily Beast: Greener waters occur when there’s more life in the ocean—particularly phytoplankton, which grow abundantly in the upper ocean depths. That might sound good, but it’s actually a grim indicator. Phytoplankton play an essential role in capturing and storing carbon dioxide—so increases in carbon dioxide inevitably give rise to phytoplankton blooms. These explosions in population mean greener waters. [Source: Neel V. Patel, The Daily Beast, July 13, 2023]

The biggest implications of the new study aren’t simply a cosmetic change for Earth’s oceans. Color changes reveal that plankton and plant populations in the oceans are changing rapidly, which could have grave impacts for marine ecosystems. For example, fish populations could take a hit—which could have downstream effects for communities that rely heavily on fishing for food and commerce. Changes to ocean health could also slowly degrade the stability of other waters around the world.

“Changes in color reflect changes in plankton communities that will impact everything that feeds on plankton,” said Dutkiewicz. “It will also change how much the ocean will take up carbon, because different types of plankton have different abilities to do that. So, we hope people take this seriously. It’s not only models that are predicting these changes will happen. We can now see it happening, and the ocean is changing.”

Dutkiewicz called the results “sobering,” adding that they represent “yet another wake-up call” about the scale of human impacts on Earth’s systems. It remains unclear whether these color changes might eventually become visible to the naked eye, but large regional tipping points could make them more noticeable in the future.

Climate Change, The Gulf Stream and the AMOC

The Gulf Stream an intense, warm ocean current in the western North Atlantic Ocean that carries warm water from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean northward along the east coast of the United States. The Gulf Stream is part of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) — a system of ocean currents that moves warm water northwards on the surface and cold, deep water southwards in the Atlantic Ocean. This "conveyor belt" is critical for regulating climate, distributing heat from the tropics to the northern latitudes, and transferring nutrients and carbon

There are major concerns that the AMOC is being negatively impacted by climate change. One study made headlines by suggesting the AMOC could collapse in just a few years, triggering major shifts in global weather patterns. The idea has inspired dramatic news coverage — and even the disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow — but the scientific picture is far more complex. [Source: Robin George Andrews, National Geographic, August 11, 2023]

Warming at the poles may be weakening the AMOC. More rainfall and melting ice add freshwater to the North Atlantic, diluting the saltier water so it sinks more slowly. Models show the AMOC is inherently unstable — capable of slowing sharply or even shutting down under the right conditions.

Ice-age climate records show that sudden bursts of freshwater once disrupted the AMOC, causing abrupt cooling across the North Atlantic. But how a slowdown would play out in today’s warmer world is uncertain. It could weaken the warm currents that moderate Europe’s climate or shift global rain belts, causing drought in some regions and heavier rains in others.

While a complete shutdown is considered unlikely in the near future. Some studies suggest the AMOC has already begun slowing, but the evidence is mixed. Continuous measurements only exist back to 2004, making long-term trends hard to pin down. Scientists have used sea-surface temperatures south of Greenland — a persistent cold patch — as a potential warning sign, but not all experts agree it reflects AMOC strength. An analysis based on that region concluded the AMOC could collapse anytime between 2025 and 2095, but even the study’s authors say the projection is not definitive.

See Separate Article: GULF STREAM, THE AMOC AND CLIMATE CHANGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Antarctic Currents Supplying Much of World's Deep Ocean with Nutrients and Oxygen Slowing Dramatically

Deep ocean currents surrounding Antarctica, crucial for sustaining marine life, slowed by 30 percent between the 1990s and 2020s and may be at risk of stopping entirely, a study published May 25, 2023 in Nature Climate Change, reveals. These currents, known as Antarctic bottom waters, are driven by dense, cold water that forms along the Antarctic continental shelf and sinks to depths exceeding 10,000 feet (3,000 meters). From there, the water flows northward into the Pacific and eastern Indian oceans, fueling the global meridional overturning circulation and supplying roughly 40 percent of the world’s deep oceans with oxygen and nutrients. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science May 26, 2023]

Warming temperatures are melting Antarctica’s ice shelves, releasing less-dense freshwater that disrupts this circulation. “If the oceans had lungs, this would be one of them,” said Matthew England, a professor of ocean and climate dynamics at the University of New South Wales and co-author of the study. Earlier research predicted a 40 percent decline in Antarctic bottom water strength by 2050, with a potential long-term collapse.

England and colleagues confirmed these predictions using observations from the Australian Antarctic Basin. Examining the flow of bottom water between 1994 and 2017, they recorded a 30 percent decrease in velocity, signaling early stagnation in these abyssal currents. Slower circulation could trap nutrients and oxygen in the deep ocean, reducing the supply of essential elements to surface ecosystems. “All of the marine life at the surface eventually sinks to the bottom, creating nutrient-rich waters,” England explained. “Slowing this circulation cuts off a key pathway for nutrients to return to the surface and support marine life.”

Each year, about 276 trillion tons of cold, salty, oxygen-rich water sink around Antarctica. Warming climates reduce the density of this water, leaving more in upper layers and disrupting circulation across the Pacific and eastern Indian oceans. The study warns that as freshwater influx continues and accelerates, these vital currents could collapse, profoundly affecting the ocean’s transport of heat, carbon, nutrients, and oxygen for centuries. Independent experts, including Ariaan Purich from Monash University, emphasized the significance of the findings. Observational evidence now complements earlier modeling studies, confirming that Antarctic ice melt is likely to have major, long-term impacts on global ocean circulation and the ocean’s role in regulating climate.

Fish Migrating Due to Warme Water

Global warming is blamed for causing warmer sea temperatures in the North Sea which in turn have causes many species of fish including cod, sole and whiting to migrate further north in search of cooler water. Water temperature moderates fish body temperature, which means warmer oceans can affect important biological processes of fish, including growth, reproduction, swimming ability and behavior. Temperature limits can also affect the distribution and abundance of bait-fish aggregations. Some species are likely to expand their geographic ranges southward (or contract their migrations northward) as waters warm. Some fish respond well to high sea temperatures, as these temperatures can shorten incubation time, increase growth rates and improve swimming ability in juvenile fish. However, these benefits are limited to relatively minor temperature increase. [Source: Australia government]

Tropical fish are appearing off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada—an unsettling change for veteran scuba diver Lloyd Bond, who has explored the region’s cold waters for more than 20 years. Bond told Phys.org that in recent years he has encountered species such as seahorses, cornetfish, triggerfish, and butterflyfish—animals native to warm tropical climates, not the frigid North Atlantic. He said he noticed his first tropical visitor about eight years ago, but sightings have surged over the past five years. “I caught a triggerfish in Mexico one year, and then I saw one here the next year,” he said. “I remember thinking, ‘Something’s not right—I shouldn’t be seeing this here.’” [Source: Jeremiah Budin, The Cool Down, December 7, 2023]

Such unexpected appearances are becoming increasingly common worldwide as human-driven warming alters weather patterns and ocean temperatures. Many animals are shifting their migration routes or moving into regions that were once far too cold for them. While a few species may adapt without major consequences, newcomers can disrupt local ecosystems, sometimes with serious ripple effects. Marine biologist Dr. Boris Worm told Phys.org that these incursions—and in some cases, permanent settlements—are now being observed in temperate waters around the globe. “It’s one of many indicators of the ongoing effects of climate change in our waters,” Worm said. “It is a symptom, not the disease.”

He pointed to lionfish as a species to watch. These invasive predators have expanded their range as ocean waters warm, often causing significant ecological damage. Similar shifts are happening on land as well, including recent sightings of a tropical wetland bird in Pennsylvania and a South American species turning up in Wisconsin.

Fish Grow Faster in Climate-Change-Warmed Water

Research by Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization indicates that climate change is affecting fish growth, with species living in warmer, shallow water growing faster and those living in cooling deep ocean waters growing slower. Ron Thresher, an oceanographer involved with the study told Reuters, “Fish growth rates are closely tied with water temperature s, so warming surface waters mean the shallow-water fish are growing more slowly than they were a century ago. The finding was made by examining 555 fish specimens aged between 2 and 128 born between 1861 and 1992 and comparing that with changes in sea temperatures obtained from 60-year-old records and data obtained from 440-year-old deep water coral.

Michael Perry of Reuters wrote: The research found fish were growing faster in waters above a depth of 250 meters (825 feet) and had slower growth rates below 1,000 meters (3,300 feet). “These observations suggest that global climate change has enhanced some elements of productivity of shallow-water stocks but at the same time reduced the productivity and possibly the resilience of deep-water stocks,” said the CSIRO’s Ron Thresher. “Growth rates in the deep-water fish are slowing because water temperatures down there have been falling, apparently for the last several hundred years.”[Source: Michael Perry, Reuters, April 27, 2007]

“Fish growth rates are closely tied with water temperatures, so warming surface waters mean the shallow-water fish are growing more quickly, while the deep water fish are growing more slowly than they were a century ago.” Populations of large marine species are subject to two major stress factors, commercial fishing and climate change, and the heavy exploitation increases the sensitivity of species to environmental effects, said Thresher.

Thresher’s team studied 555 fish specimens, such as Banded Morwong, Redfish, Jackass Morwong and Orange Roughy, from waters around Maria Island off the east coast of Australia’s island state of Tasmania. The fish were aged 2 to 128 years and had been born between 1861 to 1993. Changes in sea temperature were obtained from a 60-year-long record at Maria Island and by using 400-year-old deep-ocean corals to measure temperature at depth. The study found sea temperatures off east Tasmania had risen nearly two degrees Celsius, while a southerly shift in South Pacific winds had strengthened the warm, southerly flowing East Australian Current which runs down Australia’s east coast.

To gauge the growth rates of fish the scientists studied the earbones of eight fish species which show similar characteristics to the growth rings used to determine the age of a tree. “Average juvenile growth rates have changed significantly during the last 50 to 100 years for six of the eight species examined,” said the study published by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. Growth rates of juvenile Morwong, a coastal species which enjoys warmer waters, were 28.5 percent faster in the 1990s than in the mid-1950s, the CSIRO study found. By comparison, juvenile Oreos, a species found at depths of around 1,000 meters, were growing 27.9 percent slower than in the 1860s. The study found that the growth rates of deep-water species began decreasing before the onset of commercial fishing.

“With increasing global warming, temperatures at intermediate depths are likely to rise near-globally. This could mean that over the course of time, the decrease in growth rates for the deep-water species could slow or even be reversed,” said Thresher.

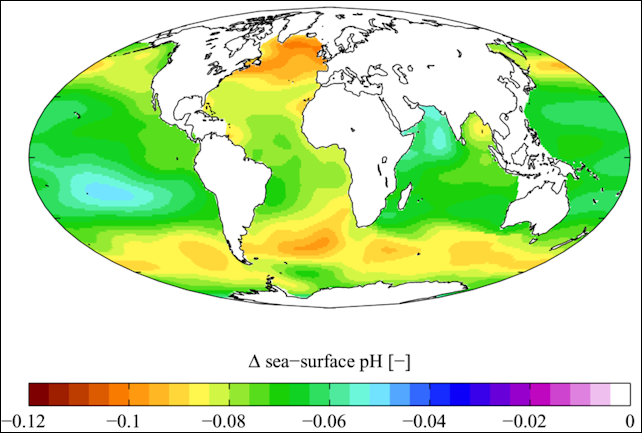

Ocean Acidification

Extra carbon dioxide molecule in sea water alters the pH level of sea water, making it slightly more acidic. In some places scientists have observed rises in acidity of 30 percent and predict 100 to 150 percent increases by 2100. The mixture of carbon dioxide and seawater creates carbonic acid, the weak acid in carbonated drinks. The increased acidity reduces the abundance of carbonate ions and other chemicals necessary to form calcium carbonate used make sea shells and coral skeletons. To get an idea what acid can due to shells remember back to high school chemistry classes when acid was added to calcium carbonate, causing it to fizz.

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in National Geographic, The pH scale, which measures acidity in terms of the concentration of hydrogen ions, runs from zero to 14. At the low end of the scale are strong acids, such as hydrochloric acid, that release hydrogen readily (more readily than carbonic acid does). At the high end are strong bases such as lye. Pure, distilled water has a pH of 7, which is neutral. Seawater should be slightly basic, with a pH around 8.2 near the sea surface. So far CO2 emissions have reduced the pH there by about 0.1. Like the Richter scale, the pH scale is logarithmic, so even small numerical changes represent large effects. A pH drop of 0.1 means the water has become 30 percent more acidic. If present trends continue, surface pH will drop to around 7.8 by 2100. At that point the water will be 150 percent more acidic than it was in 1800. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, National Geographic, April 2011]

See Separate Article OCEAN ACIDIFICATION factsanddetails.com

Ph (Acid) levels in the ocean

Image Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov/ocean and Wikimedia Commons, except giant jellyfish from Hector Garcia blog

Text Sources: Mostly NOAA, National Geographic articles. Also the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025