Home | Category: Ocean Environmental Issues / Coral Reefs

CORAL BLEACHING

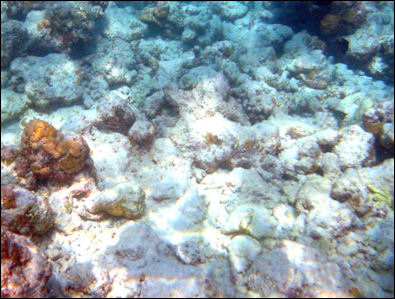

bleached corals Coral bleaching is a phenomena characterized by the changing of coral color from brown, green and pink to bleached white caused by the death of algae within the coral. If the coral can’t reestablish its bond with algae, it starves or succumb to disease. After some coral reefs die they become covered with slimy, green algae and transform into “algae-strangled rubble fields.”

Bleaching is not only bad in its own right it also destroys important fisheries and contributes to global warming. Algae in coral and the sea absorb a lot of carbon dioxide. Species such as sea anemones, sponges, and giant clams can also suffer bleaching.

In the 1980s Peter Harrison, a marine ecologist at Australia’s Southern Cross University, witnessed the first recorded large-scale coral bleaching event. Diving off Magnetic Island in the Great Barrier Reef, he was stunned by what he saw. “The reef was a patchwork of healthy corals and badly bleached white corals, like the beginnings of a ghost city,” he told National Geographic. Just months before, the same site had bustled with tropical life in Crayola colors. “Many of the hundreds of corals that I’d carefully tagged and monitored ultimately died,” he says. “It was shocking and made me aware of just how fragile these corals really are.” [Source: Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic, April 7, 2021]

Related Articles: CORAL REEFS: TYPES, PARTS, COMPOSITION AND BENEFITS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; POLLUTION IN THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GLOBAL WARMING AND THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com ; OCEAN ACIDIFICATION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED CORAL REEFS AND THEIR RECOVERY AND REBIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GLOBAL WARMING AND CORAL REEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DIRECT HUMAN IMPACTS ON CORAL REEFS: POLLUTION, OVERFISHING AND CYANIDE AND DYNAMITE FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HELPING CORAL RECOVER AND REVIVE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures ; Websites and Resources on Coral Reefs: Coral Reef Information System (NOAA) coris.noaa.gov ; International Coral Reef Initiative icriforum.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Coral Reef Alliance coral.org ; Global Coral reef Alliance globalcoral.org ;Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network gcrmn.net

Causes of Coral Bleaching

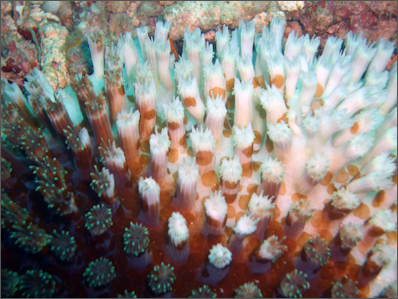

healthy coral and bleached coral High temperatures and other stresses can turn algae toxic. This often occurs when the symbiotic algae in corals produce oxygen at toxic levels as temperatures rise. When this happens, the algae may die or be ejected by the coral. This process is known as bleaching because the coral’s clear tissue and white calcium carbonate skeleton are exposed.

Bleaching can occur from a change in ocean temperature, pollution, overexposure to sunlight and low tides. Any of these influences can stress coral and causes it to release the algae that live in its tissues.Storm generated precipitation can rapidly dilute ocean water and runoff can carry pollutants — these can bleach near-shore corals. When temperatures are high, high solar irradiance contributes to bleaching in shallow-water corals. Exposure to the air during extreme low tides can cause bleaching in shallow corals.

The whitening is caused by loss of symbiotic zooxanthellare (a kind of algae) from the tissues of the coral polyps. The loss of algae, corals' primary food source, causes the coral to turn white and makes it more susceptible to disease. Sometimes healthy corals can become completely white in two or three weeks. If algae returns to the coral within a month the white coral can revive itself. But if the conditions continues for more than two months most of the coral dies.

Climate change and ocean acidification can result in mass coral bleaching events, increased susceptibility to disease, slower growth and reproductive rates, and degraded reef structure. Many scientists believe that bleaching is a natural phenomena. Others believe it is caused at least in part by human activities. They blame global warming, overfishing and pollution for contributing to the problem.

Coral bleaching effects can differ. “Climate change moves as a uniform blanket across the Earth, but there is plenty of variation in the details,” says coral ecologist Charlie Veron, former chief scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science. “Coral bleaching is patchy, and local weather conditions are key: You may have monsoon clouds protecting the reef over here, but over there it’s blue skies and the sun is hammering the water. That variability makes it especially difficult to design interventions in a broad way,"

Coral Bleaching and Ocean Temperatures

When water is too warm, corals expel zooxanthellae living in their tissues causing the coral to turn completely white. Coral bleaching generally occurs in waters that become warmer than 30 degrees C (85 degrees F). When waters get too hot the coral polyps become stressed and expel its algae. A temperature rise of 1.8 to 3.6 degrees F can trigger coral bleaching in many places.

coral bleached by El Nino

Among the causes of high water temperatures that trigger bleaching eevents are the El Niño effect and an absence of storms. Abnormal salt densities can also cause algae to die. Storms like hurricanes and typhoons help keep the water cool by churning up the water so that cooler subsurface layers of water mix with the warmer surface layers.

In 2005, the U.S. lost half of its coral reefs in the Caribbean in one year due to a massive bleaching event. The warm waters centered around the northern Antilles near the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico expanded southward. Comparison of satellite data from the previous 20 years confirmed that thermal stress from the 2005 event was greater than the previous 20 years combined. [Source: NOAA]

In January 2010, cold water temperatures in the Florida Keys caused a coral bleaching event that resulted in some coral death. Water temperatures dropped -6.7 degrees Celsius 12.06 degrees Fahrenheit lower than the typical temperatures observed at this time of year. Researchers will evaluate if this cold-stress event will make corals more susceptible to disease in the same way that warmer waters impact corals.

Major Coral Bleaching Events

Reefs all around the world are plagued by coral bleaching. Damage has been particularly bad in the Indian Ocean, where 70 percent of the coral reefs whitened or died in 1998 and 1999. The year 1998 was particularly bad for coral bleaching. About 16 percent of the world’s coral became bleached or died. Not coincidently 1998 was the second warmest year on record up to that time.

In 1998 and 2002 the Great Barrier Reef suffered major bleaching that was blamed on El Nino-related warming. Though much of damaged coral recovered about five percent was permanently damaged. In 2016, a record-hot year, 91 percent of the reefs that comprise the Great Barrier Reef bleached. Along the northern part of the reef, reefs were monitored in real time by scientists, who found that two-thirds of the corals had died.

The Great Barrier Reef was hit by four mass bleaching events between 2014 and 2021. According to National Geographic: Scientists surmise that about four decades ago severe bleaching occurred roughly every 25 years, giving corals time to recover. But bleaching events are coming faster now — about every six years — and in some places soon they could begin to happen annually.

Coral Can Recover from Bleaching and Other Stressful Events

When a coral bleaches, it is not dead. Corals can survive a bleaching event, but they are under more stress and are subject to mortality. If local threats are reduced, coral reefs have a greater chance of surviving a larger climate event, such as bleaching. [Source: NOAA]

NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program is helping local managers and communities do just that. The idea is simple. We know climate change is the single greatest global threat to coral reefs. Promoting reef resilience is a local solution. A resilient coral reef is one that can either resist a large-scale stressful event or recover from it. For this to happen, local threats must be kept to a minimum to reduce stress and improve overall reef condition. Scientists are also honing ways to evaluate how resilient a coral reef ecosystem is so that managers can take targeted actions that have the greatest impact.

Corals of the same species on the same reef can vary in tolerance levels to heat. Powerful waves Intense storms, which are becoming more frequent, damage already weakened reef structures. [Source: Fernando G. Baptista, Lawson Parker and Eve Conant, National Geographic, April 15, 2021]

El Nino Coral Bleaching Events in 2015-2016

Another severe bleaching event occurred in 2015-2016. Associated Press reported: An extended El Nino natural weather phenomenon that warmed Pacific waters near the equator triggered the most widespread bleaching ever documented. This third global bleaching event, as it was called continued into 2017 even after El Nino ended. Headlines focused on damage to Australia's famed Great Barrier Reef, but other reefs have fared just as badly or worse across the world, from Japan to Hawaii to Florida. [Source: Associated Press, March 13, 2017]

“Around the islands of the Maldives, an idyllic Indian Ocean tourism destination, some 73 percent of surveyed reefs suffered bleaching between March and May 2016, according to the country's Marine Research Center. "This bleaching episode seems to have impacted the entire Maldives, but the severity of bleaching varies" between reefs, according to local conditions, said Nizam Ibrahim, the centre's senior research officer. In some places there were startling colours just a year before the event, a dazzling array of life beneath the waves. But in 2017, some Maldivian reefs were dead. What's left is a haunting expanse of grey, a scene repeated in reefs across the globe in what has fast become a full-blown ecological catastrophe.

Worst hit have been areas in the central Pacific, where the University of Victoria's Baum has been conducting research on Kiritimati, or Christmas Island, in the Republic of Kiribati. Warmer water temperatures lasted there for 10 months in 2015-2016, killing a staggering 90 percent of the reef. Baum had never seen anything like it. "As scientists, we were all on brand new territory," Baum said, "as were the corals in terms of the thermal stress they were subjected to."

To make matters worse, scientists are predicting another wave of elevated ocean temperatures. "The models indicate that we will see the return of bleaching in the South Pacific soon, along with a possibility of bleaching in both the eastern and western parts of the Indian Ocean," said Mark Eakin, coral reef specialist and co-ordinator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Coral Reef Watch, which uses satellites to monitor environmental conditions around reefs. It may not be as bad as last year, but could further stress "reefs that are still hurting from the last two years." The speed of the destruction is what alarms scientists and conservationists, as damaged coral might not have time to recover before it is hit again by warmer temperatures.

Recovery from Coral Bleaching Caused by El Nino

Describing what he saw after a sudden increase in water temperatures around Kanton Island in the Phoenix Islands, a tiny archipelago in the central Pacific five days by boat from Fiji, Gregory Stone, wrote in National Geographic, During the El Niño of 2002-03, a body of water more than 1̊C (1.8̊F) warmer than usual had stalled for six months around the Phoenix Islands. We'd heard that the hot spot had severely bleached the region's corals. [Source: Gregory Stone, National Geographic, January 2011]

Settling down beside the reef, I saw dead coral everywhere. What had been flourishing, overlapping, overflowing brown and auburn plates of corals were now ghostly, broken reminders of their former beauty. When I'd first visited the Phoenix Islands a decade ago, these reefs had supported numerous species of hard corals, as well as giant clams, sea anemones, nudibranchs, and great populations of fish, from blacktip reef sharks to parrotfish to bohar snappers. Because the islands have remained undisturbed for so long, they'd largely avoided overfishing, pollution, and other harmful impacts of modern civilization. But they hadn't been able to avoid climate change, which most scientists believe amplifies El Niños.

Not ready to accept this setback, I was heartened to see lots of reef fish and vibrant corals growing up through the rubble — early signs of recovery. Was it possible that the reefs of the Phoenix Islands, like their mythical namesake, were rising from the ashes of a terrible warming?

In 2010 Stone returned to Kanton. He wrote: “The bleaching had killed all the coral on the lagoon floor, but almost half appeared to be growing back — the fastest recovery any of us had ever seen. The reason seemed clear: abundant fish. When coral bleaches, seaweed can grow out of control, stifling reef recovery. But fish eat the algae, keeping it from smothering the coral. Because fish populations had been protected here, the reefs remained surprisingly resilient even after suffering one of the worst bleaching events ever recorded.

Combating Coral Bleaching

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic: Since the late 1990s, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has used satellite and on-site data as well as modeling to forecast when and where bleaching is likely to occur, “giving coastal managers some lead time, a chance to ramp up protective efforts,” says Mark Eakin, the agency’s Coral Reef Watch coordinator. This early warning system has led some resource managers to limit access in vulnerable reef areas, remove rare corals proactively, and experiment with installing artificial shading. [Source: Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic, April 7, 2021]

Such “emergency” strategies aren’t cheap, and they aren’t long-term solutions. They’re also useless where coral has already died. So scientists also are trying to rebuild reefs. Helpfully, although corals are animals, they can be grown much like plants: Collect cuttings, raise them in nurseries, graft the more mature organisms onto degraded reefs, and kick-start new life.

Reuters reported: Australian scientists have come up with a model that will help researchers quickly identify soft corals most vulnerable to bleaching from marine heatwaves, helping prioritise resources to preserve reefs. Marine biologist Rosie Steinberg said her research found one type of soft coral was healthier during a heatwave and produced more algal cells than when temperatures were normal. [Source: Reuters. June 16, 2022]

"If you tried to just protect everything all at once, you'd run out of money in 10 seconds," Steinberg told Reuters from her lab at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). "So you need to know specifically, yes these are the species we need to protect, these are the species that are going to be fine no matter what we do."

Steinberg grinds up wet, frozen samples of soft coral to create a puree, which is put through a centrifuge that separates algal cells from coral protein. Researchers can then look at the quantity of protein, algal cells and chlorophyll, which are all indicators of coral health.

Soft corals take more time to bleach than hard corals but it would be "catastrophic" when they become affected, said Steinberg, who co-developed the method along with the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, the Ruhr-University Bochum and Macquarie University.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023