Home | Category: Physical Oceanography

GULF STREAM

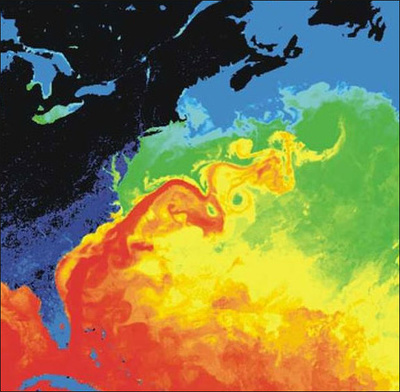

The Gulf Stream an intense, warm ocean current in the western North Atlantic Ocean that carries warm water from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean northward along the east coast of the United States. It moves north along the coast of Florida and then turns eastward off of North Carolina, flowing northeast across the Atlantic and branches into northeast-heading North Atlantic Current and southeast-heading Azores current, both of which bring warmth to Europe.

The main conveyor of heat from south to north in the Atlantic, the Gulf Stream begins in the Caribbean Sea, a relatively shallow basin. Forces from the spinning of the earth and the trade winds push Caribbean waters north and west between Cuba and the Yucatan into the Gulf of Mexico. From there is like a vast warm river, 80 kilometers wide and 500 meters deep.

The Gulf Stream process begins with the Trade Winds (blowing from east to west), which blows Atlantic waters westward to the Gulf of Mexico. Here the water is stopped by Gulf water. Because of the configuration of the geography of the Yucatan peninsula, the water is forced northward between Cuba and Florida and joins waters of the Antilles current. Around Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, where the water is around 88 degrees F in the summer and 69 degrees F in the winter, the current begins heading eastward towards Europe.

Related Articles:

OCEAN CURRENTS: FORCES, CONCEPTS, TYPES, MAPS ioa.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF OCEAN CURRENTS: GYRES, EDDIES, UPWELLING ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN TIDES: TYPES, TERMS, FORCES, MEASUREMENTS AND PREDICTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEANS, WINDS AND WEATHER ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEANOGRAPHY AND STUDYING THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WAVES IN THE OCEAN: TYPES, CAUSES, AND EFFORTS TO DESCRIBE, PREDICT AND MEASURE THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

PHYSICAL FEATURES OF THE OCEAN FLOOR: TRENCHES, VENTS, MOUNTAINS ioa.factsanddetails.com

LARGE WAVES: ROUGE WAVES, METEOTSUNAMIS AND THE BIGGEST WAVES EVER ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

The “Great Ocean Conveyor: Discovering the Trigger for Abrupt Climate Change”

by Wally Broecker Amazon.com

“Ocean Currents: Physical Drivers in a Changing World” by Robert Marsh, Erik van Sebille Amazon.com

“Ocean Currents and Their Effects on the Global Climate System” by Alexander Moreau (2025) Amazon.com

“Gulf Stream Chronicles: A Naturalist Explores Life in an Ocean River” by David S. Lee and Leo Schleicher (Illustrator) Amazon.com

“The Gulf Stream: Encounters With the Blue God” by William MacLeish(1989) Amazon.com

“Climate and the Oceans” (Princeton Primers in Climate) by Geoffrey K. Vallis Amazon.com

“The Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate Change: A Complete Visual Guide”

by Juliane L. Fry, Hans-F Graf, et al. Amazon.com

“Atmosphere, Ocean and Climate Dynamics: An Introductory Text” (International Geophysics by John Marshall, R. Alan Plumb Amazon.com

“Ocean Circulation” Open University(2001) Amazon.com

“Adrift: The Curious Tale of the Lego Lost at Sea” by Tracey Williams (2022) Amazon.com

“The Wave: In Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks, and Giants of the Ocean” by Susan Casey (2010) Amazon.com

“Waves in Oceanic and Coastal Waters” by Leo H. Holthuijsen (2007) Amazon.com

“Descriptive Physical Oceanography” by Lynne Talley (2017) Amazon.com

“Essentials of Oceanography” by Alam Trujillo and Harold Thurman Amazon.com

“The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works” by Helen Czerski, explains how the ocean influences our world and how it functions. Amazon.com

“How the Ocean Works: An Introduction to Oceanography” by Mark Denny (2008) Amazon.com

“The Science of the Ocean: The Secrets of the Seas Revealed” by DK (2020) Amazon.com

“Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics: Fundamentals and Large-Scale Circulation” by Geoffrey K. Vallis (2006) Amazon.com

“The Unnatural History of the Sea” by Callum Roberts (Island Press (2009) Amazon.com

“Ocean: The World's Last Wilderness Revealed” by Robert Dinwiddie , Philip Eales, et al. (2008) Amazon.com

“Blue Hope: Exploring and Caring for Earth's Magnificent Ocean” by Sylvia Earle (2014) Amazon.com

“National Geographic Ocean: A Global Odyssey” by Sylvia Earle (2021) Amazon.com

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)

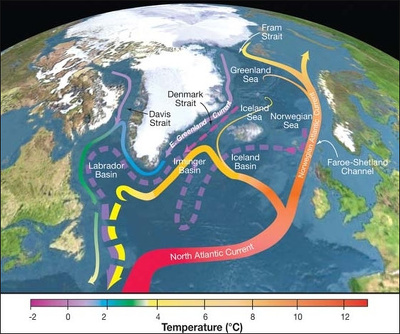

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a system of ocean currents that moves warm water northwards on the surface and cold, deep water southwards in the Atlantic Ocean. This "conveyor belt" is critical for regulating climate, distributing heat from the tropics to the northern latitudes, and transferring nutrients and carbon. Its strength is influenced by factors like temperature and salinity, and scientists are concerned that climate change could cause it to slow down, leading to more extreme weather systems globally. The Gulf Stream is an integral part of the AMOC. [Source: Google AI]

The Way the AMOC Works: Warm, salty water from the tropics flows northwards as part of the Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Current. As this water travels to the subpolar Atlantic, it cools, becomes saltier, and sinks to the ocean floor. This process is driven by heat loss to the atmosphere and the high salinity of the water. The cold, dense water then flows south along the seafloor, eventually circulating through other oceans before warming and resurfacing.

Why the AMOC is Important: The AMOC is a major global heat transport system, keeping Northern Europe's climate milder than it would otherwise be. The circulation distributes nutrients essential for marine ecosystems and moves carbon dioxide to the deep ocean. It plays a key role in determining global weather and rainfall patterns.

AMOC and the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt

In 1987, Wally Broecker of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory coined the term Global Conveyor Belt to describe this vast system of oceanic heat transport. Warm surface currents move north, releasing heat and moisture into the atmosphere. As the water cools, becomes saltier, and grows denser, it sinks in the Norwegian and Greenland Seas to form deep North Atlantic waters. These cold bottom currents flow south, while some surface waters also return south via cooler currents like the Labrador and Portugal Currents.

Because the equator receives far more direct sunlight than the poles, heat builds up in the tropics. The Earth constantly tries to rebalance this difference by sending warm air poleward and cold air equatorward, driving winds and weather systems. Most of the heat is moved by the atmosphere, but the oceans also transport it more slowly through the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt, a vast network of currents that circulates water around the world. [Source: Jeff Berardelli, CBS News, February 26, 2021]

The conveyor belt is powered by thermohaline circulation — the global movement of water driven by differences in temperature and salinity, combined with wind-driven surface flow. Dense, cold, salty water sinks; warmer, fresher water stays near the surface. As NOAA notes, the system begins in the Norwegian Sea, where heat loss to the atmosphere causes surface waters to become heavy enough to plunge to the ocean floor. That deep water then travels south past the equator to Antarctica.

The strongest part of the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt is the AMOC. It moves water at a volume equal to 100 Amazon Rivers. Warm, salty water from the Gulf Stream flows northward at the surface. Near Greenland, it cools, becomes denser, and sinks, then travels south again as deep water. Sediment cores show that the AMOC has slowed or even stopped in the past, triggering rapid climate shifts in the Northern Hemisphere. A key control on its strength is meltwater from glaciers. Fresh water is less salty and less dense, so it doesn’t sink well. Too much fresh water entering the North Atlantic can weaken or shut down the AMOC’s sinking “engine.”

Discovery of the Gulf Stream and AMOC Research

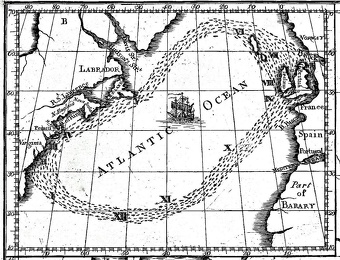

The Gulf Stream discovered by Spanish navigators and first charted by Benjamin Franklin. The first European to observe it was Ponce de Leon in 1513. The Gulf Stream route back to Europe was discovered in 1519 by the Spanish explorer Antonio de Albinos who was returning from Mexico and bravely decided to follow the currents east of Florida and north of Cuba. Before that time navigators followed Columbus’s southern route which took advantage of the prevailing westerly winds by not the strong force of the Gulf Stream current.

Franklin published a map the Gulf Stream in 1769, 200 years before a submersible named after him drifted below the surface to study this river in the ocean. In 1843, the United States Coast Survey, NOAA’s earliest “ancestor,” set out to study the Gulf Stream in more detail. They wanted to determine the depth of the water, the temperature of the water at different depths, the characteristics of the ocean bottom, the direction and velocity of the currents at different depths, and the extent of plant and animal life. Their early observations led them to discover features such as cool and warm water banding, as well as the “Charleston Bump.” [Source: NOAA]

Because of its importance to Europe’s climate, scientists closely monitor the AMOC. Since 2004, the RAPID/MOCHA array has measured temperature, salinity, and currents along 24°N, along with Gulf Stream flow and wind-driven Ekman transport. Measurements show that cross-basin transport at this latitude averages about 18.7 ± 5.6 Sverdrups (1 Sv = 1 million cubic meters per second), with large variability from year to year. Source: Robert Stewart, “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”, Texas A&M University, 2008]

Gulf Stream Speed, Weather and Fish

The Gulf Stream has an average speed of 6.4 kilometers per hour (four miles per hour). The velocity of the Gulf Stream current is fastest near the surface, with the maximum speed typically about nine kilometers per hour (5.6 miles per hour). The current slows to a speed of about 1.6 kilometers per hour (one mile per hour) as it widens to the north. The Gulf Stream transports an amount of water greater than that carried by all of the world's rivers combined. [Source: NOAA]

London is farther north than Winnipeg; Denmark has the same latitude as the Aleutians; and southern France is almost as far north as Montreal. Yet winters in much of the European continent are relatively mild. This is due the mile-deep layer of warm water carried north by the Gulf Stream.

The water from the Gulf Stream/ North Atlantic Current courses through two vast gyres (ocean-wide eddies) — the Sub-Polar Gyre and the Sub-Tropical Gyre. The Gulf Stream runs warmer or cooler for periods of about 20 years which, scientists believe, may affect the positions of the westerly winds which in turn plays a major part in determining whether it will be a warm or severely cold winter.

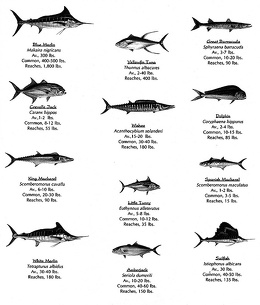

Each summer the Gulf Stream captures millions of larval newborn fish from tropical waters and deposits them along the Northeast coast of the United States. The Gulf Stream travels like a meandering river, pulling ocean water from the Gulf of Mexico along the East Coast of the United States as it moves toward Britain. As it snakes through the Atlantic, whirlpools of warm water the size of multiple city blocks spin off and grab fish and carry them north. In recent years more tropical fish than ever have been showing up in northern waters. So many of them make there way to New York that tropical fish dealers there have been begun capturing them for pet stores.

Predicted 'Missing' Blob of Water in the Atlantic Found

Scientists have identified a previously unknown water mass in the central Atlantic — a huge body of water stretching from Brazil’s northeastern tip to the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa. Called Atlantic Equatorial Water, it forms where currents along the equator mix water from the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Similar equatorial water masses had already been documented in the Pacific and Indian oceans, but never in the Atlantic. The new findings, published October 28, 2024 in Geophysical Research Letters, fill that gap. [Source: Ben Turner, Live Science, November 21, 2023]

“It was puzzling that equatorial waters existed in the Pacific and Indian oceans but appeared absent in the Atlantic, given how similar the equatorial circulation is,” Viktor Zhurbas of the Shirshov Institute of Oceanology told Live Science. “Identifying this new water mass lets us complete, or at least better define, the basic pattern of global water masses.”

Ocean water isn’t uniform — it’s a patchwork of layers and masses shaped by currents, temperature, salinity and mixing. Each water mass has distinct properties and a clear formation history, often revealed through temperature–salinity relationships that determine density. Equatorial water masses in the Pacific and Indian oceans were first recognized in 1942, but the Atlantic’s counterpart remained hidden. To look for it, researchers analyzed data from the Argo program, a global network of drifting floats that measure temperature and salinity through the water column.

In that dense dataset, the team found a subtle but distinct temperature–salinity curve parallel to those of the North and South Atlantic Central Waters — the long-missing signature of Atlantic Equatorial Water. The similarity to nearby southern waters likely helped obscure it until now. Now that it has been identified, scientists say the new water mass will help refine our understanding of how the Atlantic mixes and transports heat, nutrients and oxygen — key processes that shape global climate and marine ecosystems.

Climate Change and the AMOC

There are major concerns that the AMOC is being negatively impacted by climate change. One study made headlines by suggesting the AMOC could collapse in just a few years, triggering major shifts in global weather patterns. The idea has inspired dramatic news coverage — and even the disaster movie The Day After Tomorrow — but the scientific picture is far more complex. [Source: Robin George Andrews, National Geographic, August 11, 2023]

Warming at the poles may be weakening the AMOC. More rainfall and melting ice add freshwater to the North Atlantic, diluting the saltier water so it sinks more slowly. Models show the AMOC is inherently unstable — capable of slowing sharply or even shutting down under the right conditions.

Ice-age climate records show that sudden bursts of freshwater once disrupted the AMOC, causing abrupt cooling across the North Atlantic. But how a slowdown would play out in today’s warmer world is uncertain. It could weaken the warm currents that moderate Europe’s climate or shift global rain belts, causing drought in some regions and heavier rains in others.

While a complete shutdown is considered unlikely in the near future. Some studies suggest the AMOC has already begun slowing, but the evidence is mixed. Continuous measurements only exist back to 2004, making long-term trends hard to pin down. Scientists have used sea-surface temperatures south of Greenland — a persistent cold patch — as a potential warning sign, but not all experts agree it reflects AMOC strength. An analysis based on that region concluded the AMOC could collapse anytime between 2025 and 2095, but even the study’s authors say the projection is not definitive.

Despite the uncertainties, researchers are steadily improving their models and monitoring systems. What is clear is that an AMOC collapse would be extremely difficult to reverse — and that reducing greenhouse gas emissions is the surest way to avoid pushing the system toward a dangerous threshold.

Gulf Stream Appears to Be Weakening

A study published September 25, 2023 in Geophysical Research Letters confirmed that the Gulf Stream is almost certainly weakening. The flow of warm water through the Florida Straits has slowed by about four percent over the past 40 years — a shift with major consequences for global climate. “This is the strongest, most definitive evidence we have of the weakening of this climatically relevant ocean current,” said lead author Christopher Piecuch of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. [Source: Ben Turner, Live Science, October 17, 2023]

Gulf Stream circulation helps keep sea levels along the U.S. East Coast up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) lower than offshore waters. But as the climate warms and meltwater pours into the oceans, scientists suspect this system is slowing — or could even be pushed toward collapse. To test this, researchers examined 40 years of data from undersea cables, satellites, and direct measurements in the Florida Straits. Their analysis shows a 4 percent decline in flow strength, with only a 1 percent chance that the result is due to natural randomness.

A 4 percent shift may sound small, but it could signal the beginning of a longer, more dangerous trend. “It’s like those early days of COVID,” said Helen Czerski, an oceanographer at University College London. “The numbers start small — then they double. A week later, you have a problem.” Scientists still need to distinguish how much of the slowdown comes from natural ocean variability and how much is driven by human-caused warming. With only a few decades of detailed measurements, untangling that signal remains a challenge.

Is The AMOC Really Near a Tipping Point?

The AMOC has two stable modes: the strong, fast circulation operating today, and a much weaker one. Earlier estimates placed a potential transition sometime in the next century. But a study published July 25, 2023 in Nature Communications warns that human-driven climate change may push the system toward its tipping point far sooner. “The expected tipping point — if emissions continue as they are — is much earlier than we thought,” said co-author Susanne Ditlevsen of the University of Copenhagen. “We were actually bewildered.” [Source: Ben Turner, Live Science, July 26, 2023]

Near Greenland — where the warm, salty water normally sinks — sea surface temperatures are hitting record lows, forming a growing patch of cold water against otherwise warming seas. The last time the AMOC shifted modes during the last ice age, temperatures around Greenland soared by 10–15°C (18–27°F) within a decade. A modern collapse could cool Europe and North America by roughly 5°C (9°F) in a similarly short time.

Because direct measurements of the AMOC only began in 2004, the researchers analyzed temperature patterns in the North Atlantic from 1870 to 2020, arguing that they act as a “fingerprint” of the current’s strength. Their statistical model shows growing year-to-year instability — an early warning sign of an approaching tipping point. According to their results, the window for a potential collapse opens as early as 2025 and becomes increasingly likely later this century. The findings even unsettled the study’s authors. “It annoys me,” said co-author Peter Ditlevsen of the Niels Bohr Institute. “The window is so close and so significant that we have to take action now.”

Still, many oceanographers urge caution. Some question whether surface temperature patterns can reliably reveal changes in the AMOC. Others argue the model relies on assumptions from oversimplified circulation models that may not reflect real-world physics. “The physical foundation is extremely shaky,” said Jochem Marotzke of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, who called the results more of a “what if” exercise than a definitive forecast.

AMOC’s Fate Decided by Struggle Between Greenland Icebergs and Freshwater Runoff?

According to a study published May 30, 2024 in Science, the future of the Gulf Stream and broader the AMOC will depend on a “tug-of-war” between two kinds of Greenland melting: icebergs calving into the ocean and freshwater runoff flowing off the ice sheet. Research suggests that meltwater runoff from the Greenland Ice Sheet might help prevent icebergs from disrupting major ocean currents — though some scientists warn the picture is more complicated. [Source: Ben Turner, Live Science, June 19, 2024]

During the last ice age, between 16,800 and 60,000 years ago, enormous armadas of icebergs broke off the Laurentide Ice Sheet in what are known as Heinrich events. These sudden floods of ice and freshwater dramatically weakened the AMOC. Today, Greenland’s calving rates are comparable to mid-range Heinrich episodes, raising the question of whether similar disruptions could happen again.

Lead author Yuxin Zhou of UC Santa Barbara said their results show competing forces at work: iceberg discharge, which is highly effective at slowing ocean circulation but is beginning to level off, and meltwater runoff, which is less effective but increasing rapidly. “Those are the two influences we’re most worried about,” Zhou told Live Science.

To investigate, the team analyzed layers of sediment containing thorium-230 — a tracer diluted by freshwater from melting icebergs — to compare ancient melt events with meltwater outflow since the Industrial Revolution. They found that modern melt resembles a mid-range Heinrich event but noted key differences: during the ice age, the AMOC was already weakening before the icebergs arrived, whereas today it appears to be in relatively strong condition.

Zhou said this initial strength could offer some near-term reassurance. “Before 2100, our study suggests the AMOC is unlikely to weaken severely,” he said. Runoff may even help limit iceberg production, creating a feedback that slows calving. Still, the study does not account for other forces reshaping the Arctic and North Atlantic, including rapid ocean warming. That omission concerns some experts. The climate system during the last ice age — dominated by massive ice sheets and different meltwater pathways — behaved very differently from today’s, said University College London climate scientist David Thornalley. Those differences, combined with recent research hinting that the AMOC may already be weakening or nearing a tipping point, could be critical, he added.

Large Patch of the Atlantic Ocean near the Equator Rapidly Cooled in 2024

For several months in summer of 2024, a broad swath of ocean along the equator in the Atlantic suddenly cooled at a record-breaking pace. The region has since started to warm again, but scientists still don’t understand what triggered such a rapid temperature drop. The cold patch appeared in early June after the area had logged its warmest surface temperatures in more than 40 years. Although this part of the Atlantic naturally flips between warm and cool phases every few years, the speed of this shift was “really unprecedented,” said Franz Tuchen of the University of Miami. “We’re still scratching our heads,” added NOAA scientist Michael McPhaden, whose network of tropical buoys has been capturing real-time data. “It may be a transient feature driven by processes we don’t fully understand.” [Source Sharmila Kuthunur, Live Science, August 29, 2024]

Sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Atlantic were above 86°F (30°C) in February and March—record highs since 1982—before plunging to around 77°F (25°C) by late July. At first, forecasts suggested the region might be developing an Atlantic Niña, a rare climate pattern that boosts rainfall in West Africa and dries out northeastern Brazil. But because the cold anomaly began warming again, it no longer meets the criteria.

Typically, cooler waters in this region are driven by stronger trade winds that push warm water aside and enhance upwelling of deeper, colder water. Instead, winds southeast of the equator were unusually weak—“doing the opposite of what they should be doing,” Tuchen said. Some strong winds west of the cold patch in May may have helped start the cooling, McPhaden noted, but they don’t fully explain its speed or magnitude.

Scientists have tested several possible explanations—strong atmospheric heat loss, abrupt changes in currents or wind patterns—but none stand out. While the event is remarkable, researchers think it’s more likely part of natural climate variability than a direct result of human-caused warming. Using satellite data, buoys and other instruments, researchers are watching the region closely to understand what comes next. “It could turn out to be a consequential event,” McPhaden said. “We just have to wait and see.”

What Happens If AMOC Collapses, Slows Down or Changes Course

A weakening of the AMOC could lead to more extreme weather events, as heat would be trapped in tropical regions and northern areas would become cooler. The United Kingdom and northwestern Europe, which benefit from the warm water brought by the current, could experience colder winters. A weakening of the AMOC could impact marine ecosystems by affecting the supply of nutrients and oxygen.

Some research indicates a slowdown could have severe global consequences. According to the U.K.'s meteorological office, such a collapse would have a disastrous impact on global weather systems. It would lead to rising sea levels in the Atlantic, greater cooling and more powerful storms across the Northern Hemisphere, and severe disruption to the rainfall that billions of people in Africa, South America, and India rely on to grow crops. [Source: Ben Turner, Live Science, August 7, 2021]

A study published on August 5, 2021 in the journal Nature Climate Change attempted to resolve a hot topic of debate among scientists who investigate ocean currents: whether the recent weakening of the AMOC means it will simply circulate more slowly, which humans can reduce by lowering carbon emissions, or if it means the AMOC is about to transition to a permanently weaker state that could not be reversed for hundreds of years. "The difference is crucial," said study author Niklas Boers, a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. If it's the latter, that would mean "the AMOC has approached its critical threshold, beyond which a substantial and in practice likely irreversible transition to the weak mode could occur."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, NOAA

Text Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025