Home | Category: Ocean Environmental Issues / Coral Reefs

ENDANGERED CORAL REEFS

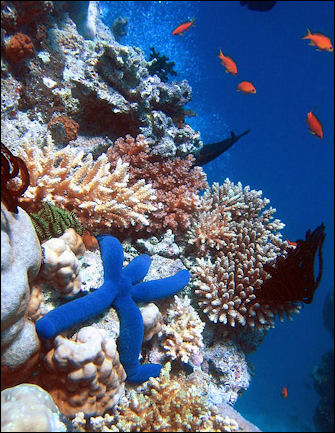

a healthy coral reef Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in National Geographic, “Coral reefs are already threatened by a wide array of forces. Rising water temperatures are producing more frequent "bleaching" events, when corals turn a stark white and often die. Overfishing removes grazers that keep reefs from being overgrown with algae. Agricultural runoff fertilizes algae, further upsetting reef ecology. In the Caribbean some formerly abundant coral species have been devastated by an infection that leaves behind a white band of dead tissue. Probably owing to all these factors, coral cover in the Caribbean declined by around 80 percent between 1977 and 2001. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, National Geographic, April 2011]

The world has lost roughly half its coral reefs between 1990 and 2020. Even if the world could halt global warming now, scientists still expect that more than 90 percent of corals will die by 2050. Without drastic intervention, we risk losing them all. "This isn't something that's going to happen 100 years from now. We're losing them right now," marine biologist Julia Baum of Canada's University of Victoria, told Associated Press. "We're losing them really quickly, much more quickly than I think any of us ever could have imagined." [Source: Associated Press, March 13, 2017]

In the Caribbean the amount of reef surface covered by live coral has fallen about 80 percent in the last three decades according to the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network. In the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Indonesia, reefs have lost about 1 percent of their coral coverage annually over the last 25 years.

Related Articles: CORAL REEFS: TYPES, PARTS, COMPOSITION AND BENEFITS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL: POLYPS, ALGAE, EGGS, MASS SPAWNS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL REEF LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; OCEAN ACIDIFICATION ioa.factsanddetails.com GLOBAL WARMING AND CORAL REEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL BLEACHING: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND RECOVERY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DIRECT HUMAN IMPACTS ON CORAL REEFS: POLLUTION, OVERFISHING AND CYANIDE AND DYNAMITE FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HELPING CORAL RECOVER AND REVIVE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures ; Websites and Resources on Coral Reefs: Coral Reef Information System (NOAA) coris.noaa.gov ; International Coral Reef Initiative icriforum.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Coral Reef Alliance coral.org ; Global Coral reef Alliance globalcoral.org ;Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network gcrmn.net

Damaged Coral Reefs

storm damaged coral

According to the Environmental Defense Fund, reefs in 93 of the 109 countries where reef are found have been damaged by human activity. A report by the United Nations estimated that 30 percent of the world's reefs have been damaged by human activity. Another report put the figure at 58 percent. Others sources have estimated that 10 percent of three world's reefs have been wiped out. A forth are regarded as degraded beyond recovery.

According to some pessimistic estimates if the pace of damage continues half of the world’s coral reefs might be lost by 2050 and another 30 percent could be seriously depleted. Optimists point out that coral reefs have survived more than 250 million years and disturbance and renewal is common among reef ecosystems and they are so vast and scattered they will survive.

Some reefs corals that were bright purple are now dull brown. Groupers living there are 60 percent smaller than they were 50 years ago and their population has declined by 95 percent. As much as 20 percent of the world’s coral reefs have effectively been destroyed by pollution, overfishing, diseases and bleaching. In some places 90 percent of the coral reefs have been lost. A survey published in Science in 2008 found that half the coral reefs in U.S. territory are in fair or poor condition.

Hurricanes and Other Natural Threats to Coral Reefs

Corals and reefs are very sensitive. Water that is too muddy, warm, salty or fresh will kill them. Natural threats to reefs include warm waters produced by the El Niño climate phenomena, storms such as typhoons and hurricanes, too much plankton, polyp-eating predators like the crown of thorn starfish and diseases.

Researchers from NOAA have suggested that hurricanes and typhoons may actually be beneficial to coral reefs in the face of global warming as they long as they don’t strike the reef directly with heavy damaging waves. The logic behind the idea is that winds mix cold deep water and warm surface water, reducing the temperature of the damaging water around the reef that is too warm. NOAA researchers studied two bleached coral reefs — one in the Florida Keys and another in the Virgin Island. The one in the Florida Keys rebounded after the passing of Hurricanes Rita and Wilma in 2005, while the one in the Virgin Islands, which was not affected by any hurricanes, did not.

Reef and Coral Diseases

diseased coral Diseases can hurt coral causing adult mortality, reducing sexual and asexual reproductive success, and impairing colony growth. Coral diseases are caused by a complex interplay of factors including the cause or agent (such as, pathogen, environmental toxicant), the host, and the environment. Coral disease often produces acute tissue loss. Staghorn coral is particularly susceptible to white band and white plague diseases.[Source: NOAA]

Reef diseases caused by natural and manmade forces include white-band disease, a slow-moving infection that causes coral tissues to peel off their skeleton and is believed to be caused by a rod-shaped bacterium; yellow-ban disease, characterized by algae loss and yellow patches on the reef; and black-band disease, an infection caused by sulphur-oxidizing and sulphur-reducing bacteria that marches across patches of coral in black band, leaving behind bleached coral. Other reef diseases found in the Caribbean include patch necrosis, white pox, white plague and rapid wasting disease. In some places unusually arm waters lead to a proliferation of coral-eating spiral shells.

In the early 1980s, a severe disease event caused major mortality throughout range of staghorn and elkhorn coral and now the population is less than 3 percent of its former abundance. The greatest threat to staghorn coral is ocean warming, which causes the corals to release the algae that live in their tissue and provide them food, usually causing death. Other threats to staghorn coral are ocean acidification (decrease in water pH caused by increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere) that makes it harder for them to build their skeleton, unsustainable fishing practices that deplete the herbivores (animals that feed on plants) that keep the reef clean, and land-based sources of pollution that impacts the clear, low nutrient waters in which they thrive.[Source: NOAA]

Damage to Coral Reefs in the Pacific by the 2015-2016 El Niño

Protected corals around the southern Line Islands — Part of the Republic of Kiribati, between 2,400 and 3,300 kilometers south of Hawaii — recovered with speed from the heat of the 2015-2016 El Niño. The coral reef around Vostok Island in went from pristine to hammered by heat to thriving again in five years. The 2015-16 El Niño killed most of the cauliflower corals, but leafy Montipora survived — and revived the reef.[Source: Byenric Sala, National Geographic, October 11, 2022]

Byenric Sala wrote in National Geographic: When we first visited in 2009: we found was paradise: reefs untouched by humans, with a thriving coral jungle full of large fish. Sharks and other top predators were so abundant that their total biomass outweighed that of their prey. On every dive we saw endangered species — such as the enormous Napoleon wrasse, up to six feet long. The southern Line Islands changed our understanding of coral reefs. Scientists like me had no idea what pristine reefs looked like.

The abundance of fish around the islands was easily explained: Because of their remoteness, about 2,000 miles south of Hawaii, there was no fishing. But would the reefs also be able to withstand global warming? In 1997-98 an intense El Niño, a cyclical warming event, had caused coral die-offs across the Pacific. The corals in the southern Line Islands, though, were in such good shape in 2009 that we believed they might be able to stand up to further ocean warming — provided they were shielded from other human assaults.

Then came a calamity. In 2015 and 2016, the strongest El Niño ever recorded moved across the Pacific. Corals die when the ocean temperature exceeds a certain threshold for too long; scientists measure a reef’s exposure to such danger in degree heating weeks (DHWs). During the 1997-98 El Niño, the southern Line Islands had suffered four DHWs. The 2015-16 event, coming on top of another two decades of global warming, pushed the DHW count to 15. The jump surprised even those of us who are well aware of the risk of ocean warming.

In 2017 a team returned to the Line Islands. “What they saw was what we had feared. Half the corals had died. My heart sank. But as more details came in , the horrible news turned into questions — and eventually, possibilities. Most of the dead belonged to one genus, the cauliflower coral Pocillopora; just one living colony was found. Though Acropora were also hit hard, no other types had suffered as much: They had all survived 15 DHWs. That meant that in the southern Line Islands, at least, all those corals were resistant to strong warming. The next question was, would Pocillopora recover, and Acropora too? Would they prove resilient?

In many parts of the Caribbean, when corals die, their skeletons are rapidly overgrown by brown seaweed. But in Stuart’s photographs from the southern Line Islands, the coral skeletons were covered by crustose coralline algae, which form a pink limestone crust. When corals reproduce, their larvae drift in the water for days, weeks, or longer before they settle to the bottom and grow into a new coral colony. Their preferred substrate to settle on? Crustose coralline algae. They don’t grow on seaweed. So the conditions were there for corals to come back in the southern Line Islands. But would they? There was only one way to find out. We had to give the reefs time and return to survey them.

Recovery and Rebirth of Coral Reefs in the Pacific

In 2021 the team returned again. After diving there Byenric Sala wrote in National Geographic: I could not believe what I saw. Had anything ever happened to this reef? The bottom was covered with live, gorgeous corals, all the way down to 100 feet. In three weeks of diving around the three southernmost Line Islands — Flint, Vostok, and Millennium (Caroline) Atoll — we measured spectacular coral recovery everywhere. The reefs were back with exuberance, but they were changed. Here and there, Pocillopora that had died in 2015-16 were recovering slowly, sometimes on top of their dead, like trees sprouting from stumps in a coppiced forest. But most of the space left by the dead corals had been filled by other species. [Source: Byenric Sala, National Geographic, October 11, 2022]

When I dived at Vostok, I thought my brain had short-circuited and I’d landed in wonderland. The reef was covered by light-blue corals that looked like giant roses — a garden of Montipora aequituberculata stretching as far as I could see. A closer look revealed dead Pocillopora, encrusted with coralline algae, under the Montipora.

How could Montipora have covered the entire reef? How could it have gone from dead cauliflowers to thriving roses in only five years? Nobody was there watching — but we had a clue: The Montipora colonies were all about the same size. That suggests to me that corals elsewhere around Vostok had been reproducing sexually and releasing millions of eggs, which soon hatched and formed a massive cloud of larvae above the reef platform. A rain of Montipora larvae may have fallen and settled on the pink crust within a day — a single event that changed the seascape for years to come.

But the coral recovery amazed us all. No one on our science team had seen anything like it. Our coral specialist, Eric Brown, a U.S. National Park Service marine ecologist, estimated the Millennium lagoon had, on average, around 43 million to 53 million coral colonies per square mile — a shocking number. We had to go through the calculation several times to believe it. It was a reminder that coral reefs do a much better job restoring themselves than any human interventions can — so long as there are enough living corals around to replenish the reefs.

The only bad news was that the giant clams that formed multicolor pavements in some areas of the Millennium lagoon were dead. In 2009 we had counted more than 29 giant clams per square yard in those areas; in 2021 three hours of swimming over the lagoon reefs revealed only five living clams. The seawater temperature in 2015-16 probably had been much higher in the lagoon than in the fore reef around the atoll. That created a lethal clam bake, from which the giant clams may never recover.

For new corals to grow over dead ones, though, the skeletons need to be covered by pink encrusting corallines instead of fleshy seaweed. What provided these ideal conditions in the southern Line Islands? We believe one reason is the off-the-charts abundance of herbivorous fish — the enormous parrotfish and schools of hundreds of surgeonfish. They’re grazers, the zebras and antelope of the reef, and they gobble every tiny fleshy alga that dares to grow on the dead coral. When you’re diving in the shallows, you hear those fish scraping at the reef nonstop. Crustose coralline algae, which have calcareous skeletons, survive the grazing. The fish prefer to eat the equivalent of yummy lettuce rather than limestone.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023