Home | Category: Physical Oceanography

PLATE TECTONICS AND THE OCEAN

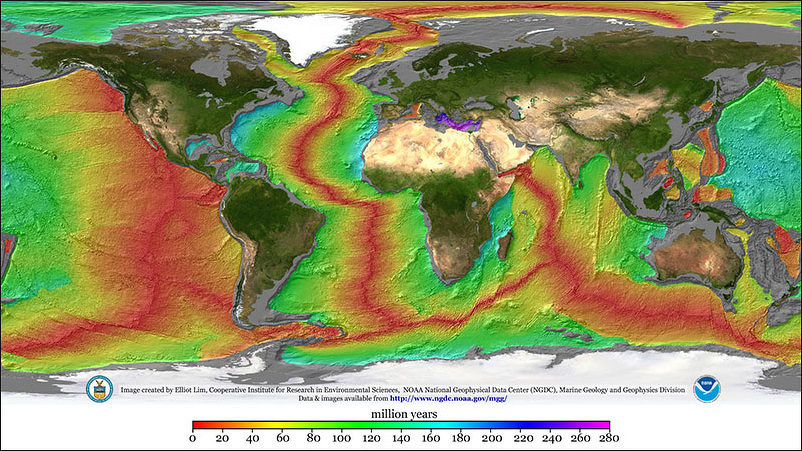

Atlantic Ocean crust

Bathymetry — the topography of the seafloor — is shaped primarily by plate tectonics. Earth’s outer rocky shell is broken into about a dozen major tectonic plates that fit together like a global jigsaw puzzle and drift slowly atop the hot, flowing mantle. Mantle convection drives this motion, causing plates to move a few centimeters per year and interact along their boundaries. [Source: NOAA, Robert Stewart, “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”, Texas A&M University, 2008]

These boundaries come in three types. At convergent margins, plates collide and one may sink beneath the other, generating earthquakes, volcanoes, and deep-sea trenches. At divergent margins, plates pull apart and rising magma forms new oceanic crust, mid-ocean ridges, seafloor volcanoes, and hydrothermal vents. Transform boundaries occur where plates slide past one another, often creating zigzag fault patterns that link neighboring convergent and divergent zones.

Earth’s crust also differs in composition and thickness. Oceanic crust is thin and dense (about 10 km thick), while continental crust is thicker and lighter (about 40 km). Because continental crust is more buoyant, it stands higher relative to sea level, giving continents an average elevation of about 1,100 meters and oceans an average depth of about 3,400 meters. As new crust forms at ridges and old crust is consumed at trenches, plate motion continually reshapes the seafloor into ridges, trenches, island arcs, and deep basins.

A modeling study published February 13, 2024 in the journal Geology suggests the Gibraltar subduction zone—long thought to be stalled—remains active and may eventually push westward into the Atlantic. The model shows that after a 20-million-year lull, the trench could resume migrating and “invade” the Atlantic, potentially helping form an Atlantic version of the Ring of Fire as new subduction zones develop and begin recycling oceanic crust. The Gibraltar arc began moving west about 30 million years ago but slowed dramatically 5 million years ago, leading some scientists to question its viability. The new simulations indicate this slowdown is temporary: the trench is struggling to advance through the narrow strait, producing low seismicity and volcanism, but still accumulating strain. Over the next 20 million years, it may push past the strait and accelerate again. If this happens, the Atlantic could eventually begin to close as subduction spreads—mirroring how the Pacific’s Ring of Fire encircles that ocean. The findings also help explain the region’s long quiet period since the 1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake, suggesting major quakes there have extremely long recurrence intervals. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, March 15, 2024]

Related Articles:

OCEANOGRAPHY AND STUDYING THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEANS OF THE WORLD: CHARACTERISTICS, FEATURES, RELATIONSHIPS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEAMOUNTS AND VOLCANOES IN THE OCEAN ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN FLOOR AND UNDERNEATH IT: SPHERULES, CIRCLES, DRILLING, FRESHWATER ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEANS: THEIR HISTORY, WATER, LAYERS AND DEPTH ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEAS AND OCEANS: DEFINITIONS, FEATURES AND THE MAIN ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ISLANDS: TYPES, HOW THEY FORM, FEATURES AND NATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

LARGE WAVES: ROUGE WAVES, METEOTSUNAMIS AND THE BIGGEST WAVES EVER ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN CURRENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org

Theory Links Ocean Volcanoes Eruptions to the Breakup of the Continents

In a paper published November 11, 2025 in the journal Nature Geoscience, researchers theorized that some mid-ocean volcanoes form from long-lived waves in Earth’s mantle, triggered by the breakup of supercontinents tens of millions ago that stripped pieces of continental crust from below and carried them oceanward to feed volcanic eruptions. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, November 14, 2025]

The study suggests that after continents rift apart, lingering mantle instabilities continue to “peel” crust from the base of continents. This continental debris then enters the mantle and later resurfaces in mid-ocean volcanoes with unusually continent-like magma — such as the Christmas Island Seamount in the Indian Ocean.

These volcanoes have long puzzled scientists because their magmas contain minerals that resemble continental rather than oceanic crust. Earlier explanations invoked recycled subducted crust or deep mantle plumes, but neither fully accounted for the diversity of magma compositions.

Analyzing volcanic rocks from the Walvis Ridge off Africa and using computer models, the team found evidence that mantle waves generated by continental breakup can sweep crustal fragments into the mantle within a few million years, with the enriched material reappearing in eruptions 5–15 million years later. This supply peaks roughly 50 million years after rifting.

Rock samples from Christmas Island match this pattern: volcanism began about 10 million years after India split from Antarctica and Australia, producing continent-rich magmas that gradually became more oceanic over the next 40–60 million years. The findings show that the mantle continues to respond to continental breakup long after oceans open, reshaping its composition and fueling volcanic chains far from their continental origins.

Giant Underwater Avalanche Reshaped the Atlantic Seafloor 60,000 Years Ago

Nearly 60,000 years ago, a massive underwater avalanche tore across the East Atlantic seabed, carving a path of destruction for more than a thousand miles. According to a study published on August 21, 2024 in the journal Science Advances the event began as a small slide in Morocco’s Agadir Canyon but rapidly expanded into a roaring flow of mud, sand, and boulders. [Source Sascha Pare, Live Science, August 30, 2024]

A 200-meter-tall wall of sediment barreled down the 400-kilometer-long canyon at roughly 65 km/h, ripping up the seafloor as it went, said co-lead author Christopher Stevenson of the University of Liverpool. Once it burst out of the canyon, the flow continued across the Atlantic seabed for another 1,600 kilometers, ultimately growing more than 100-fold—a scale far beyond anything seen in avalanches on land. This extreme growth may be a defining feature of submarine avalanches, said co-author Christoph Böttner of Aarhus University, noting that smaller underwater slides show similar behavior.

To reconstruct the event, researchers analyzed over 300 sediment cores collected over four decades, along with seismic and seabed-mapping data. Their work produced the first full map of a deep-ocean avalanche of this magnitude. After leaving the canyon, the slide spread out to blanket an area the size of Oregon with more than a meter of sediment. Though such avalanches are rarely detected in real time, a modern repeat could pose major risks. Seafloor infrastructure—including undersea internet cables that carry most global data—would be highly vulnerable, warned co-author Sebastian Krastel of Kiel University.

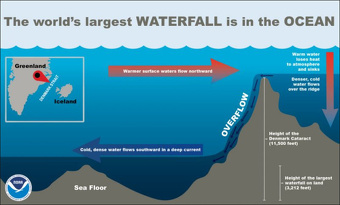

Earth’s Largest Waterfall — Is in the Ocean

The world’s largest waterfall is in the ocean beneath the Denmark Strait. Here, outhward-flowing frigid water from the Nordic Seas meets warmer water from the Irminger Sea. The cold, dense water quickly sinks below the warmer water and flows over the huge drop in the ocean floor, creating a downward flow estimated at five million cubic meters (175 million cubic feet) per second — 2,000 times the amount of water of Niagara Falls at peak flow. [Source: NOAA; Kacey Deamer, Live Science, June 9, 2016]

The Denmark Strait separates Iceland and Greenland. At the bottom of the strait are a series of cataracts that begin 610 meters (2,000 feet) under the strait’s surface and plunge to a depth of 3,505 meters (11,500 feet at the southern tip of Greenland — a drop of more than two miles — more than three times the height of Angel Falls in Venezuela, which drops water 980 meters (3,212 feet) and is considered Earth's highest aboveground uninterrupted waterfall.

But how can there be waterfalls in the ocean? It’s because cold water is denser than warm water, and in the Denmark Strait, southward-flowing frigid water from the Nordic Seas meets warmer water from the Irminger Sea. The cold, dense water quickly sinks below the warmer water and flows over the huge drop in the ocean floor, creating a downward flow. Because it flows beneath the ocean surface, however, the massive turbulence of the Denmark Strait goes completely undetected without the aid of scientific instruments. Warmer surface waters flow northward. These warmer waters gradually lose heat to the atmosphere and sink. Denser, cold water flows southward in a deep current along the sea floor over an undersea ridge in the Strait.

Underwater Lakes and Rivers in the Ocean

The oceans contains underwater lakes and rivers. These features are not made of fresh water but are instead pools and channels of super-salty, dense brine that collect in depressions on the seafloor. Known as brine pools, they resemble their land-based counterparts in that they have shorelines and waves. [Sources: Kacey Deamer, Live Science, June 9, 2016; NOAA, Google AI]

Underwater lakes form when seawater seeps through salt deposits under the ocean floor, dissolves the salt, and the resulting supersaturated, denser brine pools in low-lying areas. According to NOAA, the dissolved salt makes the surrounding water denser, causing it to settle into the depressions. Notable examples exist in the Gulf of Mexico, the Red Sea, and off the coast of Australia.

Underwater lakes and rivers can range in size from just a few neters across to several kilometers long. The water is significantly saltier and denser than the surrounding ocean, which is why it settles in one place instead of mixing with the rest of the ocean. The edges of these brine pools can be home to unique ecosystems, such as large fields of mussels that feed on bacteria that convert chemicals from the brine into energy.

“Leak” in the Bottom of the Ocean?

In 2023, scientists announced the discovery of a “leak” in sea floor off the coast of the Pacific Northwest. The “leak — technically a spring, known as Pythia’s Oasis — is likely venting water from beneath tectonic plates through the Cascadia Subduction Zone fault. Researchers worry the liquid it could increase the likelihood of a destructive earthquake as it is likely acting as a lubricant between the two plates colliding at the fault. [Source: Jackie Appel, Popular Mechanics, April 17, 2023]

Popular Mechanics reported: Technically, it’s a spring, because water is flowing in and not out. But in the ways that matter, it definitely is a leak. It’s a spring of almost-fresh water most welling up from under the ocean floor. It was accidentally discovered by then-grad-student-now-White-House-policy-advisor Brendan Philip—who spotted the bubbles that the spring carried to the surface—and a study on the vent was released by Philip and the rest of the research team from the University of Washington. “They explored in that direction and what they saw was not just methane bubbles, but water coming out of the seafloor like a firehose. That’s something that I’ve never seen, and to my knowledge has not been observed before,” Evan Solomon, a seafloor geologist and one of the authors on the paper, said.

The Cascadian Subduction Zone is a large strike-slip fault off the coast of the Pacific Northwest. That’s where two of the tectonic plates that make up the Earth’s crust meet up and slide alongside each other. And the reserve of water bubbling up from Pythia’s Oasis acts as lubrication between these two plates. “The megathrust fault zone is like an air hockey table,” Solomon said in a news release. “If the fluid pressure is high, it’s like the air is turned on, meaning there’s less friction and the two plates can slip. If the fluid pressure is lower, the two plates will lock – that’s when stress can build up.”

And therein lies the issue. If stress starts to build up, it eventually has to go somewhere. When the stress is too much and the system has to jerk into a new position, the jerk triggers an earthquake. Most likely, a big one. Scientists believe a release of stress in the Cascadia Subduction Zone could trigger a magnitude-9 earthquake that would affect many of those living in the Northwestern U.S. “Pythias Oasis provides a rare window into processes acting deep in the seafloor, and its chemistry suggests this fluid comes from near the plate boundary,” Deborah Kelley, an oceanographer and one of the authors on the study, said

age of rocks on ocean floor

Every 2.4 Million Years, Martian Gravity Changes the Ocean Floor

A study published March 12, 2024 in the journal Nature Communications suggests that Mars’ gravity may subtly tug Earth closer to the sun every 2.4 million years — warming the planet and strengthening deep-ocean currents. Researchers analyzed more than 65 million years of geological records from hundreds of global sites and found repeated cycles in which deep-sea currents alternated between strong and weak phases. These 2.4-million-year swings, known as astronomical grand cycles, appear to align with gravitational interactions between Earth and Mars. [Source: Emily Cooke, Live Science, March 13, 2024]

When the two planets enter a gravitational resonance, their tug on each other shifts the shape of their orbits. “This interaction changes planetary eccentricity,” said study co-author Dietmar Müller of the University of Sydney. As a result, Earth is pulled slightly closer to the sun for part of the cycle, receiving more solar radiation and warming.

The researchers used satellite data to track sediment buildup on the seafloor over tens of millions of years. They found gaps in the sediment record that likely reflect periods when stronger, warmer-driven deep-ocean currents — powerful eddies that can reach the abyss — scoured away accumulated material.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, NOAA

Text Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025