Home | Category: Physical Oceanography

OCEAN FLOOR

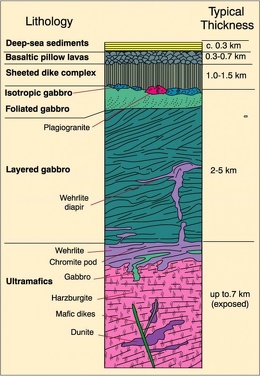

Lithology and thickness of a typical ophiolite sequence, based on the Samial Ophiolite in Oman, Boudier and Nicolas (1985) Earth Planet Sci Lett, 76, 84-92

The ocean floor in most places is composed of a layer of sediment of which there are different types: 1) Terrigenous sediment is material weathered from land, carried to the ocean by rivers and wind. 2) Biogenic sediment is the remains of dead marine organisms, such as plankton and other sea life. 3) Hydrogenous sediment is made of minerals and chemical deposits formed from seawater. 4) Cosmogenous sediment is material from space, like meteorite dust. Sediment thickness varies depending on factors like location, water depth, and ocean currents. It is generally thicker closer to continents and thinner in the deep ocean.

In 2023, scientists said they had unraveled the origins of the Melanesian Border Plateau, a massive 200-x-1,000-mile igneous “supstructure” structure beneath the Pacific east of the Solomon Islands. Research published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters shows it formed not in a single volcanic event, but through four separate volcanic episodes beginning about 120 million years ago. Unlike some volcanic pulses linked to global environmental crises, this plateau appears to have grown gradually over tens of millions of years as it drifted over mantle hotspots. The findings suggest that many other large underwater “superstructures” may also have complex, multi-phase histories. [Source: Victor Tangermann, Futurism, January 12, 2024]

Related Articles:

PHYSICAL FEATURES OF THE OCEAN FLOOR: TRENCHES, VENTS, MOUNTAINS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SEAMOUNTS AND VOLCANOES IN THE OCEAN ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

OCEANS: THEIR HISTORY, WATER, LAYERS AND DEPTH ioa.factsanddetails.com

SEAS AND OCEANS: DEFINITIONS, FEATURES AND THE MAIN ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

PHYSICS OF THE OCEAN: PRESSURE, SOUND AND LIGHT ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

DEVICES, TECHNOLOGY AND MEASUREMENTS USED IN OCEANOGRAPHY ioa.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Descriptive Physical Oceanography” by Lynne Talley (2017) Amazon.com

“Mapping the Deep: The Extraordinary Story of Ocean Science” by Robert Kunzig Amazon.com

“Essentials of Oceanography” by Alam Trujillo and Harold Thurman Amazon.com

“The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works” by Helen Czerski, explains how the ocean influences our world and how it functions. Amazon.com

“How the Ocean Works: An Introduction to Oceanography” by Mark Denny (2008) Amazon.com

“The Science of the Ocean: The Secrets of the Seas Revealed” by DK (2020) Amazon.com

“The Unnatural History of the Sea” by Callum Roberts (Island Press (2009) Amazon.com

“Ocean: The World's Last Wilderness Revealed” by Robert Dinwiddie , Philip Eales, et al. (2008) Amazon.com

“An Introduction to the World's Oceans” by Keith A. Sverdrup (1984) Amazon.com

“Blue Hope: Exploring and Caring for Earth's Magnificent Ocean” by Sylvia Earle (2014) Amazon.com

“National Geographic Ocean: A Global Odyssey” by Sylvia Earle (2021) Amazon.com

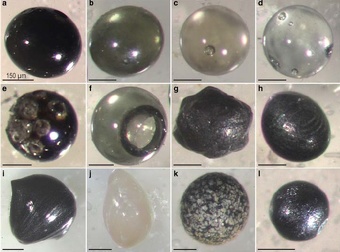

"Alien" Spherules on the Ocean Floor Explained

Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb led an expedition to recover fragments of what he claimed was an alien spacecraft that slammed into the Pacific in 2014. The object, known as CNEOS 20140108, may have been interstellar, but that alone isn’t unusual. Loeb went further, arguing it was likely alien technology—a claim requiring exceptional evidence. [Source: Cassidy Ward, SYFY, November 21, 2023]

Loeb’s team dragged a magnetic sled across the seafloor along the object’s suspected path and recovered about 50 tiny metal spherules. But such particles are extremely common on the ocean floor, coming from meteorites, human-made debris, burned spacecraft, aircraft, ships, and pollution.

For the alien-tech hypothesis to hold, the spherules would need to show non-terrestrial composition or signs of artificial design. Instead, independent analyses show the opposite: the spherules are 84 percent iron with almost no nickel, unlike meteoric iron, and their traces of beryllium, lanthanum, and uranium match byproducts of coal ash and other terrestrial industrial sources.

Even if the original object was interstellar, it likely vaporized on impact, and there’s little reason to think the recovered particles came from it—much less from alien machinery. Loeb’s interpretation stacks multiple unlikely assumptions together, far beyond what the evidence supports.

Hydrothermal Vents

Hydrothermal vents — that spew out water hotter than 260 degrees C (500 degrees F) and emit minerals such as hydrogen sulfide — are located is places in the ocean, often at great depths, where there is volcanic activity. Water seeps down through cracks in the sea floor and is heated by magma and rushes back to the surface through vents. Different chemical reactions occur where the mineral-laden vent water meets the cold water of the sea. The build up of sulfide minerals produces chimneys. Minerals nourish bacteria, which in turn feeds tube worms and mollusks that feed forms of life further up the food chain. The first ones were discovered near the Galapagos islands at a depth of 2,800 meters (9,200 feet) in 1977. A venting black smoker emits jets of particle-laden fluids. The particles are predominantly very fine-grained sulfide minerals formed when the hot hydrothermal fluids mix with near-freezing seawater. These minerals solidify as they cool, forming chimney-like structures. “Black smokers” are chimneys formed from deposits of iron sulfide, which is black. “White smokers” are chimneys formed from deposits of barium, calcium, and silicon, which are white. [Source: NOAA]

Underwater volcanoes at spreading ridges and convergent plate boundaries produce hot springs known as hydrothermal vents. Scientists that discovered hydrothermal vents in 1977, while exploring an oceanic spreading ridge near the Galapagos Islands, were amazed to the vents were surrounded by large numbers of organisms that had never been seen before. These biological communities depend upon chemical processes that result from the interaction of seawater and hot magma associated with underwater volcanoes.

Hydrothermal vents form at locations where seawater meets magma. They are the result of seawater percolating down through fissures in the ocean crust in the vicinity of spreading centers or subduction zones (places on Earth where two tectonic plates move away or towards one another). The cold seawater is heated by hot magma and reemerges to form the vents. Seawater in hydrothermal vents may reach temperatures of over 700° Fahrenheit. Hot seawater in hydrothermal vents does not boil because of the extreme pressure at the depths where the vents are formed.

Previously, sunlight was thought to be the energy source that supported the base of every food web on our planet. But organisms in these deep, dark, ecosystems have no access to sunlight, and instead metabolize hydrogen sulfide or other chemicals in a process called chemosynthesis. Since this discovery, sonar, submarines, satellites, and robots have helped find and explore this type of ecosystem and other deep ocean formations around the globe.

Lost City Hydrothermal Vents

Near the summit of a seamount west of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a maze of pale carbonate towers rises from the darkness. These formations, from tiny stacks to a 60-meter monolith called Poseidon, make up the Lost City Hydrothermal Field, discovered in 2000 about 700 meters below the surface. It is the longest-lived known vent system in the ocean. [Source: Carly Cassella, ScienceAlert, August 2022; February 5, 2025]

For at least 120,000 years, reactions between upwelling mantle rock and seawater have produced hydrogen, methane, and other gases, creating an ecosystem fueled by hydrocarbons rather than sunlight or oxygen. Warm vents support microbes, snails, and crustaceans, with occasional larger animals. The site’s chemistry has sparked scientific interest because its hydrocarbon-rich conditions resemble environments where life may have originated on Earth—and possibly on icy moons like Enceladus or Europa.

Lost City differs sharply from volcanic “black smoker” vents: its chimneys are larger, longer-lived, and produce far more hydrogen and methane. In 2024, researchers recovered a record-length core of mantle rock from the area, hoping it will shed light on early life. Although similar fields may exist elsewhere, this is the only one found so far. Despite its scientific value, the surrounding seafloor has been licensed for deep-sea mining, raising fears that sediment plumes could damage the fragile habitat. Many scientists argue the Lost City should be protected as a World Heritage site before the ecosystem is put at risk.

Vents in Giant Craters at the Bottom of the Pacific Teeming with Life

In 2025, Chinese scientists announced that they had discovered a vast new hydrothermal system on the Pacific seafloor that may offer clues to how life began on Earth. The Kunlun system, located northeast of Papua New Guinea, consists of 20 large craters arranged in a “pipe swarm.” The largest crater spans 1,800 meters wide and 130 meters deep, and the entire field covers about 11 square kilometers—making it hundreds of times larger than the Lost City hydrothermal field in the Atlantic. [Source: Patrick Pester, Live Science, September 5, 2025]

Kunlun releases exceptionally high amounts of hydrogen, produced through serpentinization, a reaction between seawater and mantle rocks. These hydrogen-rich fluids resemble the chemistry of early Earth and support diverse deep-sea communities, including shrimp, squat lobsters, anemones, and tubeworms, all reliant on chemosynthesis rather than sunlight.

Using a crewed submersible, researchers mapped the field and explored several major craters. They estimate Kunlun generates over 5 percent of the world’s non-biological submarine hydrogen output. The field likely formed through stages of hydrogen buildup, explosive release, fracturing, and mineral sealing.

Unlike the hot, volcano-driven “black smoker” vents at plate boundaries, Kunlun is a cooler, serpentinization-driven system located far from any mid-ocean ridge—a surprising geological setting. Its scale and hydrogen flux challenge long-standing assumptions about where such systems can exist and offer a new natural laboratory for studying life’s chemical origins.

Mystery of 1,300 Perfect Circles on the Mediterranean Sea Floor

Nearly 1,300 perfectly circular formations—each about 67 feet wide—were discovered 400 feet beneath the Mediterranean off Corsica. First spotted by marine biologist Christine Pergent-Martini in 2011 during sonar mapping, the rings looked like “fried eggs” on the seafloor, with a central knob and a darker outer ring. For years, their origin was a mystery. [Source: Veronique Greenwood, National Geographic, January 16, 2025]

After early ROV surveys and limited funding stalled progress, National Geographic Explorer Laurent Ballesta revived the investigation. Through a series of deep technical dives (some using a pressurized habitat that let divers stay at depth for hours), his team documented the structures, gathered core samples, and revealed a thriving, little-known deep ecosystem surrounding them.

Carbon dating stunned researchers: the rings began forming about 21,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, when sea levels were far lower and sunlight reached what is now deep water. Scientists concluded the circles are the remains of vast coralline algae domes that once grew in shallow, sunny seas. As the Ice Age ended and water levels rose, the algae died and collapsed, leaving central knobs. Over millennia, loose bits of calcium carbonate rolled downhill and were coated by rhodolith algae, settling naturally into the neat circular borders seen today.

The rings are not human-made or geological craters—they’re fossilized algae structures, reshaped by rising seas and gravity. Today they host rare corals, gorgonians, sponges, and deep-water species seldom seen in the Mediterranean. Because many rings lie beneath busy shipping routes, dropping anchors could easily destroy them. Ballesta and local marine parks are pushing for new protections. Scientists believe similar ancient formations may exist elsewhere in the Mediterranean—still hidden in the depths, awaiting discovery.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “What drew these 1,300 perfect circles on the sea floor? We may finally know.” by Veronique Greenwood, National Geographic, January 16, 2025] National Geographic

Underwater Cave So Deep Scientists Can't Find the Bottom

In April 2024, a team of researchers building in a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science that they had identified the Taam Ja' Blue Hole (TJBH), off the Mexico–Belize coast, as the deepest known cave on Earth — and they still haven’t found the bottom. [Source: Victor Tangermann, Futurism, May 4, 2024]

Once thought to be the world’s second-deepest, new measurements Science show it reaches at least 1,380 feet (420 meters) below sea level, making it the deepest confirmed blue hole. For comparison, it sits just two miles offshore, unlike Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, which lies nearly 200 miles from land. Researchers suspect the TJBH connects to a wider system of underwater caves and tunnels, potentially harboring undiscovered marine life. Blue holes often formed during past ice ages, when low sea levels and chemical weathering carved vertical shafts into limestone.

During a December scuba expedition, researchers lowered instrument probes into the sinkhole but were unable to reach the bottom. They also found that water below 1,312 feet has the same properties as Caribbean seawater, hinting at subterranean links to the open ocean.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, NOAA

Text Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025