Home | Category: Coral Reefs

CORAL REEFS

Coral reef at Palmyra The most-massive animal-made structures on earth, reefs are giant colonies, often resembling huge undersea rock outcrops, made of a layer of millions of living polyps lying in top of a supporting structure of trillions of dead coral skeletons. Reefs vary in size from a human fist to a small country. Hard stony corals, resembling brown and green colored rocks, are the major reef builders.

According to the United Nations: “reefs are "among the most biologically diverse and valuable ecosystems on Earth," providing a vital resource for an estimated 25 percent of all marine life, much of depend on reefs for their life cycles. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, roughly half a billion people also depend on reefs for food, coastal protection, tourism and fisheries' income. [Source: Li Cohen, CBS News, February 3, 2022]

Coral colonies supply 9 million tons of fish to the annual worldwide catch of 80 million tons, and produce 100,000 to 500,000 tons of limestone per square mile. Some existing reefs are 70 million years old. Reefs themselves are estimated to be over 250 million years old. The largest reefs are made up of smaller reefs. The biggest is the Great Barrier Reef, a collection of 2,900 reefs along 2,100 km of Australia's north east coast in a marine park the size of Germany.

Coral reefs provide fish, mollusks and other food for an estimated 300 million people. A study done in the early 2000s found that collectively the world’s reefs cover much less land that previously though. When added together they cover only 110,000 square miles, an about the size of Nevada, and half of what scientist thought.

Reefs are an incredibly old ecosystem. Coral, sea urchins, brittlestars, sponges and mollusk found in reefs today are closely related to species found on reefs over 200 million years ago.

Related Articles: CORAL: POLYPS, ALGAE, EGGS, MASS SPAWNS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; TYPES OF CORAL: HARD, SOFT, BRAIN, ELKHORN ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL REEF LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; REEF FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ISLANDS: TYPES, HOW THEY FORM, FEATURES AND NATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GLOBAL WARMING AND THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com ; OCEAN ACIDIFICATION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED CORAL REEFS AND THEIR RECOVERY AND REBIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GLOBAL WARMING AND CORAL REEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL BLEACHING: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND RECOVERY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DIRECT HUMAN IMPACTS ON CORAL REEFS: POLLUTION, OVERFISHING AND CYANIDE AND DYNAMITE FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HELPING CORAL RECOVER AND REVIVE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures ; Websites and Resources on Coral Reefs: Coral Reef Information System (NOAA) coris.noaa.gov ; International Coral Reef Initiative icriforum.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Coral Reef Alliance coral.org ; Global Coral reef Alliance globalcoral.org ;Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network gcrmn.net

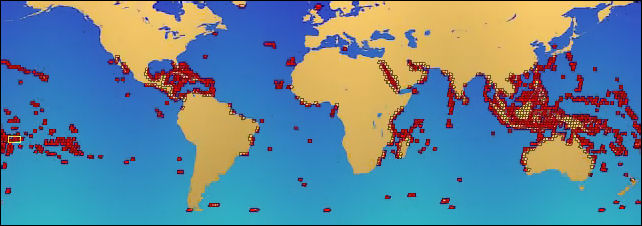

Where Coral Reefs Occur

Coral reefs are found in 109 countries. Coral colonies cover about 400,000 square kilometers (154,440 square miles, an area the size of British Columbia, or about 0.4 percent of the ocean floor). The Pacific Ocean has the most coral species. There are about twice as many coral species in Pacific Ocean reefs as in Atlantic Ocean reefs. Reef-building corals are restricted in their geographic distribution by factors such as the temperature and the salinity (salt content) of the water. The water must also be clear to permit high light penetration.

Coral reefs are found in 109 countries. Coral colonies cover about 400,000 square kilometers (154,440 square miles, an area the size of British Columbia, or about 0.4 percent of the ocean floor). The Pacific Ocean has the most coral species. There are about twice as many coral species in Pacific Ocean reefs as in Atlantic Ocean reefs. Reef-building corals are restricted in their geographic distribution by factors such as the temperature and the salinity (salt content) of the water. The water must also be clear to permit high light penetration.

Because of strict environmental restrictions, coral reefs generally are confined to tropical and semi-tropical waters. Reef-building corals cannot tolerate water temperatures below 18° Celsius (64° Fahrenheit). Many grow optimally in water temperatures between 23°–29°Celsius (73° and 84° Fahrenheit), but some can tolerate temperatures as high as 40° Celsius (104° Fahrenheit) for short periods. The diversity of reef corals — the number of species — decreases in higher latitudes up to about 30° north and south, beyond which reef corals are usually not found. [Source: NOAA]

Most reef-building corals also require very saline (salty) water ranging from 32 to 42 parts per thousand. The water must also be clear so that a maximum amount of light penetrates it. This is because most reef-building corals contain photosynthetic algae, called zooxanthellae, which live in their tissues. The corals and algae have a unique relationship. The coral provides the algae with a protected environment and compounds they need for photosynthesis. In return, the algae produce oxygen and help the coral to remove wastes. Most importantly, zooxanthellae supply the coral with food. The algae need light in order to produce food via photosynthesis.

What Coral Reef Are Made Of

A coral reef is made of thin layers of calcium carbonate. Stony corals (or scleractinians) are the corals primarily responsible for laying the foundations of, and building up, reef structures. Massive reef structures are formed when each individual stony coral organism — or polyp — secretes a skeleton of calcium carbonate. [Source: NOAA]

Most stony corals have very small polyps, averaging one to three millimeters (0.04 to 0.12 inches) in diameter, but entire colonies can grow very large and weigh several tons. These colonies consist of millions of polyps that grow on top of the limestone remains of former colonies, eventually forming massive reefs.

In general, massive corals tend to grow slowly, increasing in size from 0.5 to two centimeters (0.2 to 0.8 inches) per year. However, under favorable conditions (lots of light, consistent temperature, moderate wave action), some species can grow as much as 4.5 centimeters (1.8 inches) per year.

Evidence of 650-Million-Year-Old Reef Found in Australia

In 2008, scientists announced that they had discovered a 650 million year old reef that was once underwater in the Flinders Ranges, a mountain chain in the middle of the Australian outback. Eliza Strickland wrote in Discover magazine: Researchers say the tiny fossils they've already found in the ancient reef may be the earliest examples of multicellular organisms ever found, and may answer questions about how animal life evolved. Researcher Malcolm Wallace explains that the oldest-known animal fossils are 570 million years old. The reef in the Flinders Ranges is 80 million years older than that and was, he said, “the right age to capture the precursors to animals” [Source: Eliza Strickland, Discover magazine, September 26, 2008]

The first fossils discovered in the reef appear to be sponge-like multicellular organisms that resemble tiny cauliflowers, measuring less than an inch in diameter, but Wallace cautions that the creatures haven't been thoroughly studied yet. The reef's discovery was announced at a meeting of the Geological Society of Australia. Unlike the Great Barrier Reef, the Oodnaminta Reef — named after an old hut near by — is not made of coral. “This reef is much too old to be made of coral,” Professor Wallace said. “It was constructed by microbial organisms and other complex, chambered structures that have not been discovered before.” Coral was first formed 520 million years ago, more than 100 million years after the Oodnaminta was formed [The Times].

The first fossils discovered in the reef appear to be sponge-like multicellular organisms that resemble tiny cauliflowers, measuring less than an inch in diameter, but Wallace cautions that the creatures haven't been thoroughly studied yet. The reef's discovery was announced at a meeting of the Geological Society of Australia. Unlike the Great Barrier Reef, the Oodnaminta Reef — named after an old hut near by — is not made of coral. “This reef is much too old to be made of coral,” Professor Wallace said. “It was constructed by microbial organisms and other complex, chambered structures that have not been discovered before.” Coral was first formed 520 million years ago, more than 100 million years after the Oodnaminta was formed [The Times].

The Oodnaminta Reef formed during a very warm period in the Earth's history, which was sandwiched between two intensely cold eras, when scientists believe ice extended to the planet's equator. Researchers say the tiny organisms found in the reef may have gone on to survive one of the most extreme ice ages in Earth history which ended about 580 million years ago, apparently leaving descendents in the later life-friendly Ediacaran. "It's consistent with the argument that evolution was going on despite the severe cold," said Professor Wallace. The Ediacaran saw an explosion of complex multicellular organisms, including creatures that resembled worms and sea anemones; the sponges could be the ancestors of those species. For more on the the strange critters that flourished in the Ediacaran, see the DISCOVER article "When Life Was Odd."[The Australian].

Reef Growth

Both corals and independent algae produce calcium carbonate (limestone) which they derive from sea water. Coral polyps produce it their entire lives. Each polyp build a protective chamber. When it is finished it sends out filaments from which sprout out a new polyp. Construction begins on top of the parent polyp, which dies after it is buried.

New polyps build their coral shell on top of the exoskeletons of dead polyps. On the ocean floor when enough coral polyps have been joined together a small colony called a coral head is formed. A large coral head, about three meters in height, is often 500 years old or older. When enough coral heads are all linked together the amalgamation becomes a reef, which grows slowly at a rate of 5 to 28 millimeters a year.

Most kinds of coral need to sunlight to grow and cannot survive at depths of more than 150 meters. Damaged parts of a reef take a long time to grow back. Hard corals are considered the bricks of a reef and some have described crustose coralline algae (CCA) are the mortar that cements it together. It provides an ideal surface for coral larvae to grow on.

Boring animals drill into and honeycomb the "dead part" of the reef, while sponges, sea weed, bryozoans and algae attach themselves to it, bringing color and life. The caves, niches and crevices created in the dead coral make perfect homes and hiding places for reef fish and lobsters, who need a place to hide to survive.

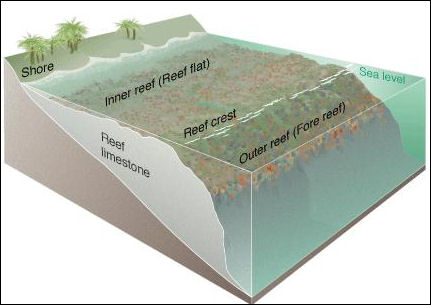

Types and Parts of Reefs

Great Barrier Reef Types of reef: 1) barrier reefs, coral breakwaters rising from the edge of a continental shelf: 2) platform reefs, irregular circles and crescents of corals that grow in calm waters; 3) patch reefs, smaller, scattered formations that grow in shallow water; and 4) fringing reefs, which grow outward from the shore. 6) Mid-shelf reefs are rounded parcels of land that emerge from continental shelves. Some develop interior lagoons; Others are topped by sandy or forested islands. 6) Ribbon reefs follow Ice Age coastlines at the edge of continental shelves. They are sometimes ravaged by storms. Different reef types are determined by proximity to the coast and depth of the water as well forces of nature that act upon them. Fringing reefs form along coasts and spread over low-lying rock foundations. Sediment can cover and choke them

The most common type of reef is the fringing reef. This type of reef grows seaward directly from the shore. They form borders along the shoreline and surrounding islands. When a fringing reef continues to grow upward from a volcanic island that has sunk entirely below sea level, an atoll is formed. Atolls are usually circular or oval in shape, with an open lagoon in the center. [Source: NOAA]

Barrier reefs are similar to fringing reefs in that they also border a shoreline; however, instead of growing directly out from the shore, they are separated from land by an expanse of water. This creates a lagoon of open, often deep water between the reef and the shore.

Reefs have been described as cities with each part playing a roll in maintaining the whole. Sponges filter the water; sea urchins and parrotfish keep coral free of light-blocking algae; the outer living layer of the reef is like skin. The most active part of the reef is the edge. This is where there is enough plankton floating in water to supply the coral with food. As new coral grow sand enlarges the reef edge, the reef further back, which doesn't get as much plankton, dies off. Scientist can drill into reefs and examine bands in the same way other scientists examine tree rings to study the age and health of the reef.

The blocking of heavy wave action by barrier reefs and islands allows sea grass beds and coastal mangrove forest to form. These in turn "trap sediments, store nutrients and serve as nurseries for a number of reef residents."

Blue Holes

Blue holes are large, water-filled sinkholes or underwater caverns distinguished by their circular openings and striking deep-blue coloration. They form in carbonate rock, typically beginning as limestone caves that developed during past ice ages when sea levels were lower. As the oceans rose, these caves flooded, and in some cases, their roofs collapsed, creating the vertical shafts now known as blue holes. Geologically, they are a type of karst feature, similar to cenotes found on land. [Source: Google AI; Darren Orf, Popular Mechanics, July 9, 2024]

Blue holes occur in shallow coastal waters around the world. Famous examples include the Great Blue Hole in Belize and the Blue Hole of Gozo in Malta, but the Bahamas has the highest concentration anywhere—over 200 lie around Andros Island alone. One of the most remarkable is Dean’s Blue Hole, near Long Island. Named after a local fisherman, it plunges to an astonishing 202 meters (663 feet), making it the third-deepest blue hole on Earth. Its depth has drawn world-class free divers and inspired local legends that claim it’s a gateway to the underworld.

Inside a blue hole, the water may be fresh, marine, or a mixture of both, and these environments often support unique or abundant marine life. Around Gozo, for example, divers encounter lobsters, moray eels, and other species. Some blue holes, including the Great Blue Hole, even allow snorkeling along the rim for a look at the wildlife from above. Diving in blue holes, however, can be challenging. Their extreme depths, low light, and sometimes unpredictable currents mean that only trained and experienced divers should venture inside. Iconic sites like the Great Blue Hole often require a minimum number of logged dives, and safe exploration always demands proper equipment, planning, and support.

Reefs and Islands

Ocean islands are basically divided into three types: 1) "low" coral and sand islands; 2) "high" islands (usually exposed peaks and ridge-tops of submerged mountains and volcanoes); 3) parts of the continental shelf. Some continental islands, were mountains and hills along the coast during last Ice Age when ocean levels were lower.

Reef islands are built through a process of coral formation known as accretion. Rubble of reef rock broken off from the reef by heavy storms such as hurricanes and typhoons create reef-top shoals. Due to the normal action of waves and ocean currents other materials begin to gradually accumulate. Beaches develop around these shallows with wind heaping up lighter material into rises, hills and dunes. The material being almost entirely made of calcium carbonate readily dissolves in rainwater and the dissolved lime is then redeposited around the loose materials, cementing it together. After a while the islands are colonized by coconuts and others plants brought in by floating seeds or flotsam and birds and insects that have deposit seeds in their feces.

An atoll is a group of islands that encircle a central lagoon. Classic atolls develop on the top guyots, flat-topped volcanic sea mounts, that rise above the sea and then erode and sink under the weight of the coral reefs that grow on their slopes.

A classic atolls begins as a reef that forms around a high island. As the island sinks under the weight of the coral reef, the coral reef grows upwards causing the island to sink even more.

See Separate Article ISLANDS: TYPES, HOW THEY FORM, FEATURES AND NATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Coral reef locations

Coral Triangle

The Coral Triangle (CT) is a roughly-triangular, tropical, marine region that spans parts of Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, the Solomon Islands and Timor-Leste covering roughly 2.3 million square miles (6 million square kilometers). While it occupies only 1.6 percent of the Earth’s oceanic area, it contains 75 percent (605) of the world’s reef-building coral species (798), the highest coral diversity in the world. The Coral Triangle has 15 regionally endemic coral species (species found nowhere else in the world), and shares 41 regional endemic species with Asia. Certain neighbouring countries, including Australia and Fiji, contain rich coral biodiversity as well, but with somewhat lower numbers. [Source: WWF, Wikipedia, Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 10, 2025]

Located between the Pacific and Indian oceans, the Coral Triangle encompasses portions of two biogeographic regions: the Indonesian-Philippines Region, and the Far Southwestern Pacific Region. The Coral Triangle has more coral reef fish diversity than anywhere else in the world: 37 percent (2,228) of the world’s coral reef fish species (6,000), and 56 percent of the coral reef fishes in the Indo-Pacific region (4,050). Eight percent (235 species) of the coral reef fishes in the Coral Triangle are endemic or locally restricted species.

The Coral Triangle is also part of an area that has emerged as one of the planet’s economic hubs. Fast population and economic growth have fueled unsustainable coastal development and boosted demand for expensive marine resources such as tuna, shark fin, turtle products and live reef fish. Current levels and methods of harvesting fish and other resources are not sustainable and place this important marine area and its people in jeopardy. A changing climate threatens coastal communities and imperils fragile reefs.

Coral Triangle Biodiversity

The Coral Triangle supports ten times more species of reef-building corals than the Caribbean and is home to six of the world’s seven sea turtle species and 37 percent of global coral reef fish. The Coral Triangle is frequented by blue whales and sperm whales (found throughout Coral Triangle waters and the Savu Sea, especially Solor-Alor region), as well as dolphins, porpoises, and the endangered dugong. Marine turtle species, including leatherbacks, are found in places such as the Northern Bird's Head Peninsula of Papua (Indonesia), as well as Lea region (Papua New Guinea) and New Georgia (Solomon Islands). [Source: WWF, Wikipedia, Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 10, 2025]

The main criteria used by scientists and conservationists to delineate the Coral Triangle were: High species biodiversity (more than 500 coral species, high biodiversity of reef fishes, foraminifera, fungid corals, and stomatopods) and habitat diversity The Coral Triangle supports livelihoods and provides income and food security, particularly for coastal communities. Resources from the area directly sustain more than 120 million people living in the area.

The Coral Triangle also supports large populations of commercially important fish. Over 120 million people live in the Coral Triangle and rely on its coral reefs for food, income and protection from storms. Tuna spawning and nursery grounds support a multi-billion dollar tuna industry and supply millions of consumers worldwide. Marine resources contribute to a growing nature-based tourism industry, valued at over US$12 billion annually.

Scientists have long been fascinated by its staggering diversity. As noted by marine biologist Nadia Santodomingo of the U.K.’s Natural History Museum (NHM), researchers have tried to understand its exceptional richness for more than a century. Even Alfred Russel Wallace, who developed the theory of natural selection alongside Charles Darwin, worked in this region while studying its remarkable biodiversity and later proposed the famous Wallace Line dividing Asian and Australian fauna.

Modern research suggests several factors contribute to the Coral Triangle’s biodiversity. Its murkier waters may provide refuge for species that struggle in clearer, more heat-prone tropical seas, offering temporary protection from climate change. The area has also been a stable biodiversity hotspot for at least 20 million years, avoiding the glaciations that disrupted ecosystems elsewhere. Its complex geology, wide variety of habitat types, and position at the crossroads of major ocean currents help sustain ideal conditions for coral larvae and support continuous species accumulation over time.

Places in the Coral Triangle with Highest Bioversity

The epicenter of that coral diversity is found in the Bird’s Head Peninsula of Indonesian Papua, which hosts 574 species (95 percent of the Coral Triangle, and 72 percent of the world’s total). Within the Bird’s Head Peninsula, the Raja Ampat archipelago is the world’s coral diversity bull’s eye with 553 species. Known as the "Amazon of the seas,” it is one of eight major coral reef zones in the world and a global hotspot of marine biodiversity. [Source: WWF; Wikipedia ]

Within the Coral Triangle, four areas have particularly high levels of endemism (Lesser Sunda Islands, Papua New Guinea – Solomon Islands, Bird’s Head Peninsula, and the Central Philippines). The center of biodiversity in the Triangle is the Verde Island Passage in the Philippines. Tubbataha Reef Natural Park in the Philippines is the only coral reef area in the region that has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The parts of the Coral Triangle that have the highest number of species comprise 6 percent of the triangle's total area. They include 1) stretches along the coast of the Philippines (including the northern coast of Luzon, the Sullivan Sea, Bohol, Mindanao, Palawan, and the Sulu Archipelago), 2) Malaysia (the northeastern coast of Sabah), 3) Indonesia (the northern and southeastern part of Sulawesi, the Banda Sea, the Mollucas, and the Raja Ampat Archipelago of Papua), 4) Papua New Guinea (the coastal areas of Madang, New Britain, Milne Bay, the Louisiade Archipelago, and Bougainville Island), and 5) the Solomon Islands (Guadalcanal Island and Makira Province). About 70 percent of the zones in the Coral Triangle are classified as low species richness areas.

The greatest extent of mangrove forest in the world is also found in the Coral Triangle. These forests’ large area and extraordinary range of habitats and environmental conditions have played a major role in maintaining the staggering biodiversity of the Coral Triangle. A joint Indonesian–U.S. marine survey expedition in 2008 discovered deep-sea biodiversity and underwater active volcanoes at a depth of 3800 meters along the western ridge. Around 40 newly identified deep-sea coral species were found there. Most are whitish in color, because the area is not a habitat for colorful algae species, which are generally shallow-living. Hydrothermal vents and coral reefs at a depth of 4000 meters were found to have created a habitat for marine niche shrimps, crabs, barnacles, and sea cucumbers.

There are three different theories as to why the Coral Triangle (East Indies Triangle) has such a high diversity of species, and each theory proposes a different explanatory model. They are usually termed the “centre of origin” model, the “centre of overlap” model, and the “centre of accumulation” model. 1) The centre of origin model posits that the high diversity populations in the area of the archipelago are part of a centrally located ancestral population that later dispersed to various peripheral locations. 2) The centre of overlap model posits that species originally in different biogeographic regions came together as a result of population division (vicariance) and later expanded their range. 3) The centre of accumulation model posits that ancestral populations that were originally scattered among peripheral locations came together in a central location and formed a diverse population.

Man-Made and Artificial Reefs

Almost any objects submerged in the sea can become an artificial reef, from sunken battleships, to intentionally sunk subway cars and oil and gas rigs and platforms. Discarded cars and junk can also make good homes for tropical sea life. In May 2006,a retired U.S. aircraft carrier, the Oriskany, was sunk off the coast of Pensacola, Florida, creating the world’s biggest artificial reef. Within two years it was covered with coral and other marine hardware and was teaming with fish and scuba divers.

Submerged shipwrecks are the most common form of artificial reef. Bridges, lighthouses, and other offshore structures often function as artificial reefs. Marine resource managers also create artificial reefs in underwater areas that require a structure to enhance the habitat for reef organisms, including soft and stony corals and the fishes and invertebrates that live among them.

Materials used to construct artificial reefs have included rocks, cinder blocks, and even wood and old tires (but the tire reef turned out not be such as great idea. Nowadays, several companies specialize in the design, manufacture, and deployment of long-lasting artificial reefs that are typically constructed of limestone, steel, and concrete. One can even be cremated and have their ashes mixed with cement and molded into the shape of a star fish or brain coral and become an artificial reef. [Source: NOAA]

Stephen Harrigan wrote in National Geographic: It took just over two minutes for the missile-tracking ship General Hoyt S. Vandenberg to sink to the bottom of the ocean. On a clear morning in May 2009, seven miles off Key West, a series of hollow booms erupted from inside the vessel’s hull, where 46 explosive charges had been buried deep below the waterline. [Source: Stephen Harrigan, National Geographic, February 2011]

“People around the world have long known that shipwrecks are prime fishing sites, and since at least the 1830s, American fishermen purposely built artificial reefs out of interlaced logs. In our own time the materials of do-it-yourself reefs have tended to be castaway junk: old refrigerators, shopping carts, ditched cars, out-of-service vending machines. Pretty much anything you can sink has the potential to become an artificial reef. Even officially sanctioned ones are often created from distinctly odd materials, including decommissioned subway cars, vintage battle tanks, armored personnel carriers, oil drilling rigs, and specially designed beehivelike modules called Reef Balls.

The process of how — or whether — a man-made hulk like the Vandenberg becomes an undersea garden is governed by variables such as depth, water temperature, currents, and the composition of the sea bottom. But most artificial reefs attract marine life in more or less predictable stages. First, where the current encounters a vertical structure like the Vandenberg, it can create a plankton-rich upwelling that provides a reliable feeding spot for sardines and minnows, which draw in predators like bluefin tuna and sharks. Next come the creatures seeking protection from the ocean's lethal openness — hole and crevice dwellers like groupers, snapper, squirrelfish, eels, and triggerfish. Opportunistic predators such as jack and barracuda are also quick to take up stations in the water column, waiting for their prey to show themselves. In time — maybe months, maybe years, maybe a decade, depending on the ocean's moods — an alien expanse of raw steel will be encrusted with algae, tunicates, hard and soft corals, and sponges, sprouting life everywhere like a giant Chia Pet.

For decades in the Gulf of Mexico, oil and gas platforms have been prime fishing sites for recreational anglers, since many species of fish seek shelter in their underwater structures. "The economic benefit of artificial reefs is very clear," says Michael Miglini, the captain of a 36-foot charter boat called Orion that takes fishermen and divers out to rigs off Port Aransas. "Creating habitat is akin to creating oases in the desert. An artificial reef is a way of boosting the ocean's capacity to create fish, to increase the life of the Gulf."

Some biologists worry that artificial reefs simply attract fish from natural reefs and may become killing zones for certain sought-after fish, such as red snapper, one of the Gulf's most harvested game fish and presumably one of the species that would gain the most by having new habitat in which to flourish. "When it comes to red snappers, artificial reefs are bait," says James H. Cowan, Jr., a professor in the Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences at Louisiana State University. "If success is judged solely by an increase in harvest, then artificial reefs are pretty successful. But if those structures, which are usually deployed in shallow waters to make them more accessible to fishing, are pulling fish off natural reefs farther from the coast, they may actually be increasing the overfishing of species that are already under stress."

Benefits of Reefs

coral head Coral reefs are important to humans because they bring in billions of dollars through tourism, protect coastal homes from storms, support promising medical treatments, and provide a home for millions of aquatic species. Coral reefs grow in and around about a third of world's tropical shorelines. The provide fish, mollusks and other food for an estimated 300 million people, erosion protection for beaches and an estimated $375 billion worth of storm protection a year. Economically coral reefs generate billions of dollars a year worldwide in tourism, recreation and fishing. [Source: Douglas Chadwick, National Geographic, January 1999]

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in National Geographic, “The reefs that corals maintain are crucial to an incredible diversity of organisms. Somewhere between one and nine million marine species live on or around coral reefs. These include not just the fancifully colored fish and enormous turtles that people visit reefs to see, but also sea squirts and shrimps, anemones and clams, sea cucumbers and worms — the list goes on and on. The nooks and crevices on a reef provide homes for many species, which in turn provide resources for many others. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, National Geographic, April 2011]

Reefs are home to 10 percent of the world's fish catch and provide natural breakwaters to protect land from storms. During extremely low tides, sometimes large expanse of reef are exposed. Protected lagoons and other areas created by wave-breaking reefs allow the formation of sea grass beds and mangrove swamps that incredible rich habitats in their own right but also are important areas where many forms of sea life breed and live out the early stages of their life.

"Something like 25 percent of all species in the oceans spend at least part of their life in coral reef systems," Ken Caldeira, an oceanographer at the Carnegie Institution, told National Geographic. "Corals build the architecture of the ecosystem, and it's pretty clear if they go, the whole ecosystem goes."

Limestone produced over the eons and millennia by coral is now used in concrete and masonry. Metamorphosed limestone (marble) has been used by Michelangelo and sculptors to produce great works of art and by builders and architects to create great buildings and structures.

Drugs from Reefs

Scientists are searching the coral reefs and the sea, the same way they are searching in the rainforests, for miracle drugs. Some drugs have already been found. More seem on the way. The study of virus-killing chemicals in a Caribbean sponge in the 1950s led to the discovery of the AIDS-fighting drug AZT as well as Acyclovir, used to treat herpes infections. These have been called the first marine drugs. Sponges have also yielded cytarabine, a treatment for a kind of leukemia.

barrel sponge Coral reefs are sometimes considered the medicine cabinets of the 21st century. Coral reef plants and animals are important sources of new medicines being developed to treat cancer, arthritis, human bacterial infections, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease, viruses, and other diseases. Since corals are stationary animals, many have evolved chemical defenses to protect themselves from predators. Scientists continue to research the medicinal potential of these substances. In the future, coral reef ecosystems could represent an increasingly important source of medical treatments, nutritional supplements, pesticides, cosmetics, and other commercial products. [Source: NOAA]

Eleutherobin, a chemical that comes from a mottled, yellow, pickled-shaped soft coral found off the coast of Australia, and a similar chemical from a sponge and a Mediterranean coral have been shown to stop the growth of malignant tumors. Dolastatin is a drug taken from an Indian ocean sea hare that shows promise in treating skin cancer and has made it as far as the clinical trial stage. A painkiller derived from a blue-green algae found near Curacao is being studied.

Some of the toxins found in soft corals are anti-inflammatory agents that have the potential of treating cancer, AIDS, asthma, heart disease and a host of other ailments. Scientist have found that toxins used by some nudibranchs to repel fish also work on land in bug sprays. The calcium secreting mechanisms of coral are being studied as means for repairing bones. Potential non-addictive painkillers have been discovered in sea whips and cone snails.

Scientists are examining the mucous coating on clownfish that protects it from sea anemone toxins for various used. They are also checking out chemicals exuded by coral that protect them from sunburn during low tide for new waterproof sun protection cream.

See Sea Squirts, Sponges, Cone Snails.

How Coral Reefs Benefit the Economy and Protect Property

Healthy coral reefs support commercial and subsistence fisheries as well as jobs and businesses through tourism and recreation. In the U.S., approximately half of all federally managed fisheries depend on coral reefs and related habitats for a portion of their life cycles. The National Marine Fisheries Service estimates the commercial value of U.S. fisheries from coral reefs is over $100 billion. Local economies also receive billions of dollars from visitors to reefs through diving tours, recreational fishing trips, hotels, restaurants, and other businesses based near reef ecosystems. [Source: NOAA]

Despite their great economic and recreational value, coral reefs are severely threatened by pollution, disease, and habitat destruction. Once coral reefs are damaged, they are less able to support the many creatures that inhabit them. When a coral reef supports fewer fish, plants, and animals, it also loses value as a tourist destination.

Great Barrier Reef The coral reef structure buffers shorelines against waves, storms, and floods, helping to prevent loss of life, property damage, and erosion. When reefs are damaged or destroyed, the absence of this natural barrier can increase the damage to coastal communities from normal wave action and violent storms.Several million people live in U.S. coastal areas adjacent to or near coral reefs. Some coastal development is required to provide necessary infrastructure for coastal residents and the growing coastal tourism industry.

Despite their great economic and recreational value, coral reefs are severely threatened by pollution, disease, and habitat destruction. Once coral reefs are damaged, they are less able to support the many creatures that inhabit them. When a coral reef supports fewer fish, plants, and animals, it also loses value as a tourist destination.

The impacts of coastal development (such as, marina, dock, and bridge construction, dredging to replenish beaches) and polluted runoff from coastal areas can damage coral reefs over the long term. Therefore, the health of coral reefs depends on sustainable coastal development practices that protect sensitive coral ecosystems and the creatures that reside there.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025